Alfian Sa'at1 Don Marquis Once Wrote a Poem About a Fly Who

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberto Caeiro's

UCLA Carte Italiane Title Playing God: Alberto Caeiro’s “Num meio-dia de fim de primavera” and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s La Ricotta Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8tv1n97r Journal Carte Italiane, 2(10) ISSN 0737-9412 Author Cabot, Aria Zan Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.5070/C9210023697 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Playing God: Alberto Caeiro’s “Num meio-dia de fim de primavera” and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s La ricotta Aria Zan Cabot University of Wisconsin-Madison Ciò di cui viene dissacrata la innocenza non è l’arte ma l’autore. Pier Paolo Pasolini, “L’ambiguità” This paper examines the relationship between “creators” (gods and poets) and their creations in the poem “Once at mid-day in late spring” (“Num meio-dia de fim de primavera”) by the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935)—but ostensibly authored by Alberto Caeiro, one of the numerous fictional heteronyms through which Pessoa published entire works in verse and prose—and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s short film,La ricotta (1963). I focus in particular on Pessoa and Pasolini’s displacement of a divine subject onto a human object and of creative authority onto secondary authors. Secondly, I consider the playfulness inherent in the irreverent rejection of the institutionalization of artistic and religious creation in the poem and the film, as well as the use of bucolic settings that revive a kind of pre-historical, pre-Christian religiosity in a landscape that is nonetheless distinct from traditional “pastoral” modes due to the constant interruption of modern systems of production and representation. -

INTRODUCTION: the RIDDLE of the BACCHAE Pier Paolo

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION: THE RIDDLE OF THE BACCHAE 'Euripides says so many things in this play'. T. B. L. Webster, Tragedies of Euripides, 276 Pier Paolo Pasolini, the Italian poet, writer and cineast, who lived from 1922 to 1975, was particularly influenced in his work by Greek tragedy . 1 In Teorema, one of the most difficult of his films to understand, he stages a dramatic situation which appears to be a reflection of Euripides' Bacchae. 2 An unknown, silent visitor comes one day into a wealthy bourgeois family (the father is a Milan industrialist), and arouses in the whole family, father, mother, son, daughter, and their maid, an erotic desire which leads each one of them to a psychological crisis. The visitor leaves as suddenly as he appeared, but their love for him caused a radical change in those he leaves behind. The maid, Emilia, who represents the peasant proletariat, returns to her birthplace, where she becomes a saint and works miracles; she is buried alive, but her tears continue to flow and become a spring. The bourgeois characters too are transformed: the daughter lies perpetually paralysed in bed; the son becomes an abstract painter, but realizes his failure and at the end of the film urinates against his paintings. Lucia, the mother, drives in her car along the pavements of the Milan streets, looking for young men for whom she can be a whore, while the father gives his factory to his workers, and in the last sequence of the film, surrounded by the crowds in Milan station, he strips, runs outsided, and, naked, climbs the bare, smoking heights of a volcano. -

The Soundscape of Pier Paolo Pasolini's the Gospel According To

Nicola Martellozzo The Soundscape of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) ABSTRACT Il Vangelo secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to St. Matthew, IT/FR 1964), by the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, is one of the most interesting and widely acclaimed film representations of the life of Jesus. Its reception in the Catholic world has reflected the alternating fortunes of Pasolini himself, but over the years critics have come to fully appreciate its merits. While the director made faithful use of the dialogue in the Gospel, he constructed a new – but plausible – imagination, or “architecture of reality”, based on an intertextual code with intersecting pictorial, architectural, biblical and sound references. This essay aims in particular to employ a semiotic approach to an- alyse the musical motifs in the film and the way in which they convey precise meanings and values to the viewer about the figure and life of Jesus. Songs and musical compo- sitions are leitmotifs that punctuate the narrative, interweaving with the visual compo- nent to form a full-blown language in its own right. KEYWORDS Pier Paolo Pasolini; The Gospel According to St. Matthew; Musical Leitmotifs; Intertex- tuality; Audio-visual Syntax BIOGRAPHY Nicola Martellozzo graduated from the University of Bologna with a degree in cultural anthropology and ethnology. The author of an essay on the phenomenology of religious conversion (2015), he has presented papers at various specialist conferences (Italian Society of Medical Anthropology 2018; Italian Society of Cultural Anthropology 2018; Italian Society of Applied Anthropology; Italian National Professional Association of An- thropologist 2018). -

Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1968)

Christel Taillibert Théorème (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1968) Né en 1922, Pier Paolo Pasolini n'a cessé tout au long de sa vie de fustiger la société, ses conservatismes, ses hypocrisies et ses impostures. A la fois poète, essayiste, romancier et cinéaste, son art sera avant tout l'expression d'un être en souffrance, en rage contre un système dans lequel il ne se reconnaîtra jamais et qui jamais ne l'acceptera. De remous en véritables scandales, aucun de ses films ne laisse indifférent. Que ce soit en termes moraux, religieux ou politiques, Pasolini endure tout au long de sa carrière les foudres de ses - nombreux - détracteurs. Théorème, œuvre polysémique signée en 1968, est particulièrement symptomatique des passions que ses films étaient capables de déchaîner à l'époque. Générique Scénario, dialogue, réalisation : Pier Paolo Pasolini D'après le roman de Pier Paolo Pasolini, "Teorema" (Garzanti Editore, 1968) Interprétation : Terence Stamp (le visiteur), Massimo Girotti (Paolo, le père), Silvana Mangano (Lucia, la mère), Anne Wiazemsky (Odetta, la fille), Andres José Cruz (Pietro, le fils), Laura Betti (Emilia, la servante), Ninetto Davoli (Angiolino, le messager), Susanna Pasolini (la paysanne) Image : Giuseppe Ruzzolini (Eastmancolor) Décors : Luciano Puccini Costumes : Marcella De Machis Effets spéciaux : Goffredo Roccheti Montage : Nino Baragli Musique : Ennio Morricone et extraits du Requiem de Mozart Production : Aetos Film Producteurs : Franco Rossellini, Manolo Bolognini Directeur de production : Paolo Frasca Distribution : Coline / Planfilm Durée : 98 mn Résumé Un jeune homme aussi charmeur que silencieux débarque un beau jour dans une famille bourgeoise de Milan. Tour à tour, tous les occupants de la maison se laissent séduire - intellectuellement comme physiquement - par l'étrange visiteur. -

Pasolini's Medea

Faventia 37, 2015 91-122 Pasolini’s Medea: using μῦθος καὶ σῆμα to denounce the catastrophe of contemporary life* Pau Gilabert Barberà Universitat de Barcelona. Departament de Filologia Clàssica, Romànica i Semítica [email protected] Reception: 01/02/2012 Abstract From Pasolini’s point of view, Medea’s tragedy is likewise the tragedy of the contemporary Western world and cinema is the semiology of reality. His Medea thus becomes an ancient myth pregnant with signs to be interpreted by attentive viewers. The aim of this article is to put forward reasoned interpretations based on a close analysis of the images and verbal discourses (lógoi) of Pasolini’s script, ever mindful of the explanations given by the director himself that have been published in interviews, articles and other texts. Keywords: Pier Paolo Pasolini; Medea; Greek tragedy; classical tradition; cinema; semiology Resumen. La Medea de Pasolini: utilizar μῦθος καὶ σῆμα para denunciar la catástrofe del mundo contemporáneo Desde el punto de vista de Pasolini, la tragedia de Medea equivale a la tragedia del mundo con- temporáneo y el cine es la semiología de la realidad. Su Medea deviene así un mito antiguo repleto de signos que requieren la interpretación de espectadores atentos. El objetivo de este artículo es proponer interpretaciones razonadas basadas en el análisis minucioso de las imágenes y de los dis- cursos verbales (lógoi) del guion de Pasolini, siempre desde el conocimiento de las explicaciones dadas por el mismo director publicadas en entrevistas, artículos y otros textos. Palabras clave: Pier Paolo Pasolini; Medea; tragedia griega; tradición clásica; cine; semiología * This article is one of the results of a research project endowed by the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia “Usos y construcción de la tragedia griega y de lo clásico” –reference: FFI2009-10286 (subprograma FILO); main researcher: Prof. -

Moma and LUCE CINECITTÀ CELEBRATE the ENDURING INFLUENCE of ITALIAN FILMMAKER PIER PAOLO PASOLINI with a COMPREHENSIVE RETROSPECTIVE of HIS CINEMATIC WORKS

MoMA AND LUCE CINECITTÀ CELEBRATE THE ENDURING INFLUENCE OF ITALIAN FILMMAKER PIER PAOLO PASOLINI WITH A COMPREHENSIVE RETROSPECTIVE OF HIS CINEMATIC WORKS Accompanying Events include an Evening of Recital at MoMA; Programs of Performances and Film Installations at MoMA PS1; a Roundtable Discussion, Book Launch and Seminar, and Gallery Show in New York Pier Paolo Pasolini December 13, 2012–January 5, 2013 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, December 12, 2012—The Museum of Modern Art, Luce Cinecittà, and Fondo Pier Paolo Pasolini/Cineteca di Bologna present Pier Paolo Pasolini, a full retrospective celebrating the filmmaker’s cinematic output, from December 13, 2012 through January 5, 2013, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters. Pasolini’s film legacy is distinguished by an unerring eye for cinematic composition and tone, and a stylistic ease within a variety of genres—many of which he reworked to his own purposes, and all of which he invested with his distinctive touch. Yet, it is Pasolini’s unique genius for creating images that evoke the inner truths of his own brief life that truly distinguish his films. This comprehensive retrospective presents Pasolini’s celebrated films with newly struck prints by Luce Cinecittà after a careful work of two years, many shown in recently restored versions. The exhibition is organized by Jytte Jensen, Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art, and by Camilla Cormanni and Paola Ruggiero, Luce Cinecittà; with Roberto Chiesi, Fondo Pier Paolo Pasolini/Cineteca di Bologna; and Graziella Chiarcossi. Pasolini’s (b. Bologna, 1922-1975) cinematic works roughly correspond to four periods in the socially and politically committed artist’s life. -

EXHIBITION GUIDE Floorplan Introduction

EN The Mystery of the Body In Dialogue with Lucas Cranach and Pier Paolo Pasolini EXHIBITION GUIDE Floorplan Introduction 11 The current exhibition presents Berlinde De Bruyckere’s artistic in- 7 terpretation of the «mystery of the body» in dialogue with a selection 6 of works by Lucas Cranach and Pier Paolo Pasolini. The show vividly 9 First Floor illustrates the German Renaissance painter’s and the Italian movie 8 5 9 director’s influence on the contemporary Flemish sculptor’s draw- 3/4 1 ings and sculptures of the last seven years. 10 The body has always been a «mystery» in the sense that it can never 2 be comprehended fully. It is one of the most commonly portrayed subjects, and each generation of artists discovers it anew. To have unlimited access to the human body in the age of digitiza- tion is an extraordinary challenge, and we find ourselves increasingly 1 Berlinde De Bruyckere: Schmerzensmann V (2006) confronted with more absurd ideals of beauty. Moreover, on the in- 2 Berlinde De Bruyckere: Romeu ‘my deer’ (2011) ternet we can subject bodies to violence in a virtual world without 3 Pier Paolo Pasolini: Il Vangelo secondo Matteo (1964) having to bear the consequences of our actions. Such circum- 4 Pier Paolo Pasolini: Teorema (1968) stances impact how we see and deal with the body, and this is often 5 Berlinde De Bruyckere: Into One-Another-Series (2010–2011) reflected in art. Our perception of reality is colored by how the body is 6 Lucas Cranach the Elder: Schmerzensmann (ca. -

Pier Paolo Pasolini: the GOSPEL ACCORDING to ST. MATTHEW

October 9, 2018 (XXXVII:7) Pier Paolo Pasolini: THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO ST. MATTHEW (1964, 137 min.) Online versions of The Goldenrod Handouts have color images & hot links: http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html DIRECTED BY Pier Paolo Pasolini WRITTEN BY Pier Paolo Pasolini PRODUCED BY Alfredo Bini MUSIC Luis Bacalov CINEMATOGRAPHY Tonino Delli Colli EDITING Nino Baragli PRODUCTION DESIGN Luigi Scaccianoce SET DECORATION Andrea Fantacci COSTUME DESIGN Danilo Donati MAKEUP Marcello Ceccarelli (makeup artist), Lamberto Marini (assistant makeup artist), Mimma Pomilia (hair stylist) ART DEPARTMENT Dante Ferretti SOUND Fausto Ancillai (sound mixer), Mario Del Pezzo (sound) VISUAL EFFECTS Ettore Catalucci COSTUME AND WARDROBE Piero Cicoletti (assistant Renato Terra...Un indemoniato costumer), Piero Farani (wardrobe) Eliseo Boschi...Giuseppe D'Arimatea Natalia Ginzburg...Maria di Betania CAST Enrique Irazoqui...Cristo PIER PAOLO PASOLINI (b. March 5, 1922 in Bologna, Margherita Caruso...Maria (giovane) Emilia-Romagna, Italy—d. November 2, 1975 (age 53) in Ostia, Susanna Pasolini...Maria (vecchia) Rome, Lazio, Italy) was published poet at 19 and had already Marcello Morante...Giuseppe written numerous novels and essays before his first screenplay in Mario Socrate...Giovanni Battista 1954. His first film Accattone (1961) was based on his own Settimio Di Porto...Pietro novel. He was arrested in 1962 when his contribution to Alfonso Gatto...Andrea Ro.Go.Pa.G. (1963) was considered blasphemous. The original Luigi Barbini...Giacomo Italian title of The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964), a Giacomo Morante...Giovanni realistic, stripped-down presentation of the life of Christ, Il Giorgio Agamben...Filippo vangelo secondo Matteo, pointedly omitted “Saint” in St. -

The Passion of Pasolini by Nathaniel Rich

The Passion of Pasolini By Nathaniel Rich September 27, 2007 Pierpaulo Pasolini P.P.P.: Pier Paolo Pasolini and Death edited by Bernhart Schwenk and Michael Semff, with the collaboration of Giuseppe Zigaina Catalog of an exhibition at the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 208 pp. (2005) Pasolini: A Biography by Enzo Siciliano, translated from the Italian by John Shepley Bloomsbury, 436 pp. (1982) Pasolini Requiem by Barth David Schwartz Vintage, 785 pp. (1992) Stories from the City of God: Sketches and Chronicles of Rome, 1950–1956 by Pier Paolo Pasolini, edited by Walter Siti and translated from the Italian by Marina Harss Handsel, 232 pp. (2003) 1. The murder of Pier Paolo Pasolini, like much of his life's work, seems to have been designed expressly to provoke shock, moral outrage, and public debate. His mutilated corpse was found on a field in Ostia, just outside of Rome, on November 2, 1975. He had been repeatedly bludgeoned and then, while still alive, run over by his own car. The next day, the Roman police received a confession from a seventeen-year-old street hustler named Giuseppe Pelosi, nicknamed "Pino la Rana" ("Joey the Frog"). Pelosi claimed that Pasolini had tried to rape him, and that he had killed the famous filmmaker and writer in self- defense. But the physical evidence showed that most of Pelosi's story had been fabricated—including, most significantly, his assertion that he and Pasolini had been alone.[1] If at first Pelosi's story did not seem far-fetched, it was only because the openly homosexual Pasolini had a well-publicized, if largely exaggerated, reputation as a sexual predator. -

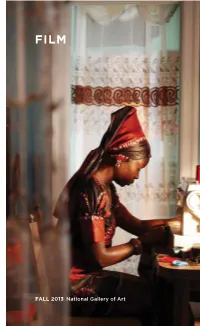

National Gallery of Art Fall 2013 Film Program

FILM FALL 2013 National Gallery of Art 11 Art Films and Events 18 The Play’s the Thing: Václav Havel, Art and Politics 22 Richard Wagner Revisited 25 American Originals Now: Moyra Davey 27 Pier Paolo Pasolini 32 Réalité Tales: Young French Cinema Mamma Roma p. 32 nga.gov/film cover: Mother of George p. 12 Unless otherwise noted, films are screened in the East Fall 2013 celebrates a rich history and vibrant new Building Auditorium, Fourth Street and Pennsylvania cinema through area premieres, in-person presentations, Avenue NW. Works are presented in original formats, and unique retrospectives. The influence and legacy of and seating is on a first-come, first-seated bases. Doors two of Europe’s most distinguished twentieth-century open thirty minutes before each show and programs artistic and political figures is explored in two programs. are subject to change. First, The Play’s the Thing: Václav Havel, Art and Politics focuses on the playwright-statesman’s long-standing For more information, e-mail [email protected], relationships with Prague’s Theatre on the Balustrade call (202) 842-6799, or visit nga.gov/film. and with visionary directors of the Czech New Wave. Second, a retrospective of the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922–1975) is offered following the 90th anniversary of his birth last year. Richard Wagner Revisited includes lec- tures and screenings that explore the composer’s lasting significance in the arts, while Réalité Tales: Young French Cinema introduces Washington audiences to films associ- ated with the contemporary Paris-based alliance known as Association du Cinéma Indépendant pour sa Diffusion (ACID). -

Gender and Migrant Roles in Italian Neorealist and New Migrant Films: Cinema As an Apparatus of Reconfiguration of National Identity and ‘Otherness’

humanities Article Gender and Migrant Roles in Italian Neorealist and New Migrant Films: Cinema as an Apparatus of Reconfiguration of National Identity and ‘Otherness’ Marianna Charitonidou 1,2,3 1 Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), Department of Architecture, ETH Zurich, Stefano-Franscini-Platz 5, CH 8093 Zürich, Switzerland; [email protected] 2 School of Architecture of National Technical University of Athens, 42 Patission Street, 106 82 Athens, Greece 3 Faculty of Art History and Theory of Athens School of Fine Arts, 42 Patission Street, 106 82 Athens, Greece Abstract: The article examines an ensemble of gender and migrant roles in post-war Neorealist and New Migrant Italian films. Its main objective is to analyze gender and placemaking practices in an ensemble of films, addressing these practices on a symbolic level. The main argument of the article is that the way gender and migrant roles were conceived in the Italian Neorealist and New Migrant Cinema was based on the intention to challenge certain stereotypes characterizing the understanding of national identity and ‘otherness’. The article presents how the roles of borgatari and women function as devices of reconceptualization of Italy’s identity, providing a fertile terrain for problematizing the relationship between migration studies, urban studies and gender studies. Special attention is paid to how migrants are related to the reconceptualization of Italy’s national narrations. The Neorealist model is understood here as a precursor of the narrative strategies that one encounters in numerous films belonging to the New Migrant cinema in Italy. The article also explores how certain aspects of more contemporary studies of migrant cinema in Italy could illuminate our understanding of Neorealist cinema and its relation to national narratives. -

Contrasting Corporealities in Pasolini's La Ricotta Jill Murphy

1 Dark Fragments: Contrasting Corporealities in Pasolini’s La ricotta Jill Murphy, University College Cork Abstract: The short film La ricotta (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1963) tells the story of Stracci, an extra working on a film of the life of Christ, which is presented in part via tableaux vivants of Mannerist paintings. Pasolini’s film is replete with formal, stylistic and narrative binaries. In this article, I examine a particularly emphatic binary in the film in the form of the abstract, ethereal corporeality of the Mannerist paintings versus the raw and bawdy corporeality of Stracci. I show that through the reenactment of the paintings and their literal embodiment, Pasolini creates a rapprochement and, ultimately, a reversal between the divine forms created by the Mannerists and Stracci’s unremitting immanence, which, I argue, is allied to the carnivalesque and the cinematic body of Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp. I examine how Pasolini gradually deposes the Mannerists, and thus the art-historical excesses and erotic compulsion he feels towards the crucifixion, substituting in their place the corporeal form of Stracci in all its baseness and profanity. Introduction The corporeal—the quality and materiality of the body—is a driving force that accompanies more formal considerations throughout Pier Paolo Pasolini’s cinematographic work. From the physicalities of Accattone (1961) and Mamma Roma (1962), through the celebration of the carnivalesque and the sexual in the “Trilogia della vita” films, to the corporeal transgressions of Pigsty (Porcile, 1969) and Salò, or the 120 days of Sodom (Salò, o le 120 giornate di Sodoma, 1975), Pasolini is consistently guided by a deep-rooted sense of the physical in a range of guises.