PASOLINI a Film by Abel Ferrara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brooklyn Law School Associate Professor Joc- Among the Staff and Children Here at St

Volume 65, No. 198 TUESDAY, JANUARY 28, 2020 50¢ Borough QUEENS brass Veteran cops TODAY with Queens ties January 28, 2020 rise in the ranks By David Brand Queens Daily Eagle A 6,000-SQUARE-FOOT PLAY SPACE Three veteran police officers with Queens for young children opened in Forest Hills on ties were appointed to NYPD leadership po- Friday, Time Out reports. Dream City includes sitions by Police Commissioner Dermot Shea a mural by Queens artist Rob Anderson, as Friday at 1 Police Plaza well as swings, a play food stand and a ball pit. Shea, a Sunnyside native, promoted Assis- The play space caters to children from ages tant Chief David Barrere to Chief of Housing, 1-6 and is located at 108-48 Queens Blvd. Assistant Chief Ruben Beltran to borough commander of Queens South and Assistant Chief Juanita Holmes as the Commanding “I’VE MET SO MANY GREAT PARENTS Officer of the School Safety Division. and families in the Forest Hills community “These are talented leaders and I am where my four-year-old son and two-year-old thrilled with the experience and vision each daughter have been growing up. We wanted brings to their role,” Shea said. “Together, we to create a space where children can dream, will take Neighborhood Policing to the next discover and play, while simultaneously NYPD Commissioner Dermot Shea appointed three officers with Queens ties to new level, particularly as it relates to engaging our offering a place for parents to connect and leadership positions. Photo by Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office Continued on page 19 network,” Dream City Founder Corrie Hu said. -

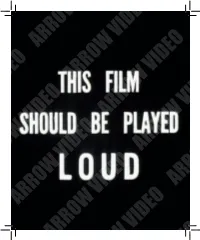

Arrow Video Arrow Vi Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow

ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 1 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Music Composed and Performed by THE DRILLER KILLER Joseph Delia Reno … Jimmy Laine [Abel Ferrara] Editors Carol … Carolyn Marz Pamela … Baybi Day Orlando Gallini Dalton Briggs … Harry Schultz Bonnie Constant Landlord … Alan Wynroth Michael Constant [ ] Nun … Maria Helhoski Jimmy Laine Abel Ferrara Man in Church … James O’Hara Special Effects Carol’s Husband … Richard Howorth ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Knife Victim … Louis Mascolo David Smith Attacker … Tommy Santora Director of Photography Derelicts Ken Kelsch Produced by Hallway … John Coulakis Rooftop … Lanny Taylor Navaron Films Bus Stop … Peter Yellen ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Executive Producer Empire State … Steve Cox Street Corner … Stephen Singer Rochelle Weisberg Street Corner … Tom Constantine Screenplay Sidewalk and Street … Anthony Picciano Fire Escape … Bob De Frank N.G. St. John Roosters Directed by ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Abel Ferrara Tony Coca-Cola (guitar) … Rhodney Montreal [D.A. Metrov] And Dedicated to the People of New York Ritchy (bass) … Dicky Bittner Steve (drums) … Steve Brown “The City of Hope” ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 2 3 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO CONTENTS 2 The Driller Killer Cast and Crew 7 All Around, In the City (2016) ARROW VIDEOby Michael Pattison ARROW VIDEO 16 Mulberry St. Crew 17 The Memory of a Reality (2016) by Brad Stevens ARROW26 About the VIDEORestoration ARROW VIDEO 4 5 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ALL AROUND, IN THE CITY by Michael Pattison On 31 October 1977, horror struck the front page of the Village Voice. -

Elmore Leonard, 1925-2013

ELMORE LEONARD, 1925-2013 Elmore Leonard was born October 11, 1925 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Due to his father’s position working for General Motors, Leonard’s family moved numerous times during his childhood, before finally settling in Detroit, MI in 1934. Leonard went on to graduate high school in Detroit in 1943, and joined the Navy, serving in the legendary Seabees military construction unit in the Pacific theater of operations before returning home in 1946. Leonard then attended the University of Detroit, majoring in English and Philosophy. Plans to assist his father in running an auto dealership fell through on his father’s early death, and after graduating, Leonard took a job writing for an ad agency. He married (for the first of three times) in 1949. While working his day job in the advertising world, Leonard wrote constantly, submitting mainly western stories to the pulp and/or mens’ magazines, where he was establishing himself with a strong reputation. His stories also occasionally caught the eye of the entertainment industry and were often optioned for films or television adaptation. In 1961, Leonard attempted to concentrate on writing full-time, with only occasional free- lance ad work. With the western market drying up, Leonard broke into the mainstream suspense field with his first non-western novel, The Big Bounce in 1969. From that point on, his publishing success continued to increase – with both critical and fan response to his works helping his novels to appear on bestseller lists. His 1983 novel La Brava won the Edgar Award for best mystery novel of the year. -

A Simple Curve

A Simple Curve Directed By Aubrey Nealon Canada, Drama, Running Time: 92 minutes Distributor Contact: Josh Levin Film Movement Series 109 W. 27th St., Suite 9B, New York, NY 10001 Tel: 212-941-7744 ext. 213 Fax: 212-941-7812 [email protected] A Simple Curve Synopsis Caleb is 27, and was raised in the majestic Kootenay Mountains by his bush hippie parents. He loves his father Jim and understands his reverence for wood working, coriander and Soya products, but he just doesn't get Jim's determined effort to achieve economic disaster at every turn. His father is a relentlessly unsuccessful business man, and as the junior partner in their carpentry shop, Caleb is powerless to stop the fiscal self- sabotage. When Matthew, an old friend of Jim's, arrives in the valley to develop a high- end fishing lodge, Caleb sees fortune looming, provided he can keep his father distracted long enough. But a small deception leads to colossal betrayal, and soon Caleb must face the fact that he's reached that treasured day when a boy becomes man enough to tell his father to f**k right off. Festival Awards & History Leo Awards - 2005 WINNER- Best Cinematography in a Feature Length Drama WINNER- Best Supporting Performance by a Female in a Feature Length Drama Nominated for 9 others, including: BEST Film, BEST Actor and BEST Director. Nantucket Film Festival - 2006 WINNER- Best Writer/Director Official Selection: Toronto International Film Festival 2005 Vancouver International Film Festival 2005 Belfast Film Festival 2005 Brisbane International Film Festival -

Abel Ferrara

A FILM BY Abel Ferrara Ray Ruby's Paradise, a classy go go cabaret in downtown Manhattan, is a dream palace run by charismatic impresario Ray Ruby, with expert assistance from a bunch of long-time cronies, sidekicks and colourful hangers on, and featuring the most beautiful and talented girls imaginable. But all is not well in Paradise. Ray's facing imminent foreclosure. His dancers are threatening a strip-strike. Even his brother and financier wants to pull the plug. But the dreamer in Ray will never give in. He's bought a foolproof system to win the Lottery. One magic night he hits the jackpot. And loses the ticket... A classic screwball comedy in the madcap tradition of Frank Capra, Billy Wilder and Preston Sturges, from maverick auteur Ferrara. DIRECTOR’S NOTE “A long time ago, when 9 and 11 were just 2 odd numbers, I lived above a fire house on 18th and Broadway. Between the yin and yang of the great Barnes and Noble book store and the ultimate sports emporium, Paragon, around the corner from Warhol’s last studio, 3 floors above, overlooking Union Square. Our local bar was a gothic church made over into a rock and roll nightmare called The Limelite. The club was run by a gang of modern day pirates with Nicky D its patron saint. For whatever reason, the neighborhood became a haven for topless clubs. The names changed with the seasons but the core crews didn't. Decked out in tuxes and razor haircuts, they manned the velvet ropes that separated the outside from the in, 100%. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

ADRIANA ASTI Biografia Cinema

VIALE PARIOLI, 72 – 00197 ROMA TEL. 0636002430 – FAX 0636002438 [email protected] www.carolleviandcompany.it ADRIANA ASTI Biografia Esordisce a teatro nel 1951 e ottiene il primo successo personale con una parte ne Il crogiuolo di Arthur Miller, diretta da Luchino Visconti, che più avanti le offrirà alcuni ruoli nei film Rocco e i suoi fratelli (nei panni della ragazza della lavanderia) e Ludwig (dove interpreta Lila Von Buliowski). A teatro ha recitato in Santa Giovanna di George Bernard Shaw (1984), Giorni felici di Samuel Beckett (1985, 2010), La locandiera di Carlo Goldoni (1986) e il dramma Tre uomini per Amalia (1988). Vincitrice del premio Siae (1990) e del premio Duse (1993), nel 1999 ha scritto e interpretato Alcool. Nel 2000 ha interpretato in francese Ferdinando, un classico della drammaturgia degli anni ottanta. Al cinema ha interpretato il ruolo della prostituta Amore in Accattone (1961) di Pier Paolo Pasolini, grande amico dell'attrice, e quello dell'affascinante zia del protagonista in Prima della rivoluzione (1964), di Bernardo Bertolucci. Ha recitato in Il fantasma della libertà (1974), di Luis Buñuel; Un cuore semplice (1977) e Tosca e altre due (2003), entrambi di Giorgio Ferrara, fratello di Giuliano e suo attuale marito; Io, Caligola di Tinto Brass (1979), Bimba - È clonata una stella(2002), debutto cinematografico di Sabina Guzzanti; La meglio gioventù (2003) (con cui vince il suo terzo Nastro d'Argento e il Ciak d'oro) e Quando sei nato non puoi più nasconderti (2005), entrambi di Marco Tullio Giordana; L'ultimo Pulcinella(2008), di Maurizio Scaparro. Per la tv è stata tra i protagonisti della miniserie La famiglia Ricordi, con la regia di Mauro Bolognini (1995). -

NEO-NOIR / RETRO-NOIR FILMS (1966 Thru 2010) Page 1 of 7

NEO-NOIR / RETRO-NOIR FILMS (1966 thru 2010) Page 1 of 7 H Absolute Power (1997) H Blondes Have More Guns (1995) H Across 110th Street (1972) H Blood and Wine (1996) H Addiction, The (1995) FS H Blood Simple (1985) h Adulthood (2008) H Blood Work (2002) H Affliction (1997) H Blow Out (1981) FS H After Dark, My Sweet (1990) h Blow-up (1967).Blowup H After Hours (1985) f H Blue Desert (1992) F H Against All Odds (1984) f H Blue Steel (1990) f H Alligator Eyes (1990) SCH Blue Velvet (1986) H All the President’s Men (1976) H Bodily Harm (1995) H Along Come a Spider (2001) H Body and Soul (1981) H Ambushed (1998) f H Body Chemistry (1990) H American Gangster (2007) H Body Double (1984) H American Gigolo (1980) f H Bodyguard, The (1992) H Anderson Tapes, The (1971) FSCH Body Heat (1981) S H Angel Heart (1987) H Body of Evidence (1992) f H Another 48 Hrs. (1990) H Body Snatchers (1993) F H At Close Range (1986) H Bone Collector, The (1999) f H Atlantic City (1980) H Bonnie & Clyde (1967) f H Bad Boys (1983) F H Border, The (1982) F H Bad Influence (1990) F H Bound (1996) F H Badlands (1973) H Bourne Identity, The (2002) F H Bad Lieutenant (1992) H Bourne Supremacy, The (2004) h Bank Job, The (2008) H Bourne Ultimatum, The (2007) F H Basic Instinct (1992) H Boyz n the Hood (1991) H Basic Instinct 2 (2006) H Break (2009) H Batman Begins (2005) H Breakdown (1997) F H Bedroom Window, The (1987) F H Breathless (1983) H Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007) H Bright Angel (1991) H Best Laid Plans (1999) H Bringing Out the Dead (1999) F H Best -

Carolina Di Domenico

MARIA VITTORIA GRIMAUDO TALENT MANAGEMENT Rodolfo Corsato ________________________www.rodolfocorsato.com______________________ LINGUE CONOSCIUTE Inglese, Francese FORMAZIONE Diplomato alla “BOTTEGA TEATRALE DI VITTORIO GASSMAN” FIRENZE 1986-1987 CINEMA 2011 “CHA CHA CHA” Regia Marco Risi Ruolo: Carbone (Cameo) Prodotto dalla Bibi Film di Angelo Barbagallo 2011 “IO E TE” Regia Bernardo Bertolucci Partecipazione Straordinaria Evento Speciale Festival di Cannes 2012 2005 "QUANDO SEI NATO NON PUOI PIU' NASCONDERTI" Regia Marco Tullio Giordana In concorso al FESTIVAL DI CANNES 2005 (co-protagonista, ruolo Popi) Candidato Nastro D'Argento 2006 miglior attore non protagonista Con Alessio Boni, Michela Cescon, Adriana Asti Produzione: Rai Cinema e Cattleya in coproduzione Limited (UK), Babe (FR) "Once you're born you can no longer hide" (English Title) "Une fois que te es ne" (French Title) 2005 "MANUALE D'AMORE" Regia Giovanni Veronesi Co-protagonista, ep. "Tradimento" con Carlo Verdone, Margherita Buy, Luciana Littizzetto, Silvio Muccino, Sergio Rubini, Jasmine Trinca. Ruolo Alberto Marchese Produzione: Aurelio e Luigi De Laurentis (campione d'incassi 2005) "Leçons d'amour a L'Italienne" (Francia) - "The Handbook of Love" (USA) Premio come attore "Mirto D'oro" Festival di Poggio Mirteto (RI) Premio come attore "Fausto Tozzi" Festival di Casaprota (RI) 2004 "L'AMORE E' ETERNO FINCHE' DURA" Regia Carlo Verdone Co-protagonista, ruolo Andrea con Laura Morante, Carlo Verdone, Stefania Rocca "Love is eternal while it last" (English Title) Produzione: Medusa e Vittorio Cecchi Gori Premio "Attore Rivelazione" Festival delle Cerase 2004 Premio come attore "Mirto D'oro" Festival di Poggio Mirteto 2004 (RI) 2003 "DE REDITU" Il Ritorno Regia Claudio Bondi Co-protagonista ruolo Minervio con Roberto Herlitzka "The Voyage Home" (English Title) Produzione: Misami Film di A.V. -

BAM 2009 Next Wave Festival Opens with the U.S. Premiere of In-I Featuring Juliette Binoche and Akram Khan

BAM 2009 Next Wave Festival opens with the U.S. premiere of In-I featuring Juliette Binoche and Akram Khan Engagement marks the final performances of the dance collaboration between the Oscar-winning actress and world renowned choreographer BAMcinématek presents Rendez-vous with Juliette Binoche film series In-I Directed and performed by Juliette Binoche and Akram Khan Set design by Anish Kapoor Lighting design by Michael Hulls Music by Philip Sheppard Costume design (Juliette Binoche) by Alber Elbaz Costume design (Akram Khan) by Kei Ito Sound design by Nicolas Faure Co-produced by Hermès Foundation: National Theatre, London; Théâtre de la Ville, Paris; Grand Théâtre de Luxembourg; Romaeuropa Festival and Accademia Filarmonica Romana, Rome; La Monnaie, Brussels; Sydney Opera House, Sydney; Curve, Leicester BAM Harvey Theater (651 Fulton St) Sept 15, 17–19, 22–26 at 7:30pm Sept 16 at 7pm* Sept 20 at 3pm Tickets: $25, 50, 70 718.636.4100 or BAM.org *2009 Next Wave Gala: Patron Celebration. For more information, contact BAM Patron Services 718.636.4182 BAMcinématek: Rendez-vous with Juliette Binoche September 11—30 BAM Rose Cinemas (30 Lafayette Avenue) Tickets: $11 per screening for adults; $8 for seniors 65 and over, children under twelve, and $8 for students 25 and under with valid I.D. Monday–Thursday, except holidays; $7 BAM Cinema Club members. Call 718-636-4100 or visit BAM.org Artist Talk with Juliette Binoche & Akram Khan September 17, post-show (free for ticket holders) Brooklyn, NY/August 10, 2009—BAM’s 2009 Next Wave festival opens with the U.S. -

Locating Salvation in Abel Ferrara's Bad Lieutenant

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 7 Issue 1 April 2003 Article 4 April 2003 'It all happens here:' Locating Salvation in Abel Ferrara's Bad Lieutenant Simon J. Taylor [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Taylor, Simon J. (2003) "'It all happens here:' Locating Salvation in Abel Ferrara's Bad Lieutenant," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'It all happens here:' Locating Salvation in Abel Ferrara's Bad Lieutenant Abstract Bad Lieutenant offers a both a narrative and a theology of salvation. Both are focussed on the death of the Lieutenant at the end of the film. This essay traces these accounts of salvation and finds that they are both flawed, in nature and scope. These flaws derive from an exclusive focus on the death of the Lieutenant and the cross of Christ as the loci of salvation. The value of Ferrara's work is in the articulation of these flaws, as they point to dangers for Christian theology as it seeks to articulate the salvation offered by Christ. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss1/4 Taylor: 'It all happens here' At the end of Abel Ferrara's film Bad Lieutenant (1992), the Lieutenant (never named and referred to in the credits simply as Lt) sits in his car in front of a sign that reads 'It all happens here'.