Football Bowl Subdivision Records

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minn M Footbl 2005 6 Misc

GOPHER FOOTBALL TABLE OF CONTENTS 2005 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE THIS IS GOLDEN GOPHER FOOTBALL Longest Plays . .156 Miscellaneous Records . .156 The Mason Era . .4 Team Records . .157 Minnesota Football Tradition . .6 Metrodome Records . .159 Minnesota Football Facilities . .8 Statistical Trends . .160 Golden Gophers In The NFL . .12 H.H.H. Metrodome . .162 Minnesota’s All-Americans . .14 Memorial Stadium . .163 Game Day At The Metrodome . .16 Greater Northrop Field . .163 TCF Bank Stadium . .18 Year-by-Year Records . .164 National Exposure . .20 All-Time Opponent Game-by-Game Records . .164 H.H.H. Metrodome . .21 All-Time Opponents . .168 Big Ten Bowl Games . .22 Student-Athlete Development . .24 HISTORY Academics . .26 1934/1935 National Champions . .169 Strength & Conditioning . .28 1936/1940 National Champions . .170 Home Grown In Minnesota . .30 1941/1960 National Champions . .171 Walk-On Success . .32 The Little Brown Jug . .172 The University of Minnesota . .34 Floyd of Rosedale . .172 University Campus . .36 Paul Bunyan’s Axe . .173 The Twin Cities . .38 Governor’s Victory Bell . .173 Twin Cities Sports & Entertainment . .40 Retired Numbers . .174 Alumni of Influence . .42 All-Time Letterwinners . .175 Minnesota Intercollegiate Athletics . .44 All-Time Captains . .181 Athletics Facilities . .46 Professional Football Hall of Fame . .181 College Football Hall of Fame . .182 2005 TEAM INFORMATION All-Americans . .183 2005 Roster . .48 All-Big Ten Selections . .184 2005 Preseason Depth Chart . .50 Team Awards . .185 Roster Breakdown . .51 Academic Awards . .186 Returning Player Profiles . .52 Trophy Award Winners . .186 Newcomer Player Profiles . .90 NFL Draft History . .187 All-Time NFL Roster . .189 GOLDEN GOPHER STAFF Bowl Game Summaries . -

First-Place Los Angeles Rams Host New England Patriots on Thursday Night Football

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Andrew Howard – 310.845.4579 NFL Media – 12/9/20 [email protected] FIRST-PLACE LOS ANGELES RAMS HOST NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS ON THURSDAY NIGHT FOOTBALL Patriots-Rams Thursday at 8:20 PM ET on FOX, NFL Network & Amazon Prime Video ‘NFL GameDay Kickoff’ Airs at 6:00 PM ET on NFL Network ‘FOX NFL Thursday’ Airs at 7:30 PM ET The 2020 Thursday Night Football Presented by Bud Light Platinum season continues Thursday, December 10 when defensive tackle Aaron Donald and the Los Angeles Rams host quarterback Cam Newton and the New England Patriots at 8:20 PM ET on FOX, NFL Network and Amazon Prime Video. FOX Sports’ lead play-by-play announcer Joe Buck, and Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback and FOX Sports’ lead analyst Troy Aikman, along with sideline reporters Erin Andrews and Kristina Pink call the action from SoFi Stadium. Additionally, FOX’s NFL Rules expert Mike Pereira joins to give explanations on officiating and rules throughout the game. Alongside the FOX broadcast, Hannah Storm and Andrea Kremer call the game on Amazon Prime Video. New this year, Prime members can also tune-in to the ‘Scout’s Feed’ which features Bucky Brooks, Daniel Jeremiah and Joy Taylor. NFL Network’s pregame coverage begins at 3:00 PM ET with TNF First Look hosted by Andrew Siciliano. At 6:00 PM ET on NFL Network, NFL GameDay Kickoff previews the Patriots-Rams matchup, with host Colleen Wolfe live from SoFi Stadium and analysts Joe Thomas, Steve Smith Sr. and Michael Irvin on remote. -

Up and Running

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK » TODAY’S ISSUE U DAILY BRIEFING, A2 • TRIBUTES, A7 • WORLD, A8 • BUSINESS, B5 • CLASSIFIEDS, B6 • PUZZLES, C3 MAKING GOOD AT THE NEXT LEVEL MURDER CHARGE TRUMP-ERA TV 50% Billy Goodall excels at Mt. Union Bristolville man, 18, indicted Screenwriters challenged OFF SPORTS | B1 LOCAL | A5 VALLEY LIFE | C1 VOUCHERS. DETAILS, A2 FOR DAILY & BREAKING NEWS LOCALLY OWNED SINCE 1869 TUESDAY, JUNE 27, 2017 U 75¢ CBO: Senate health bill adds 22M uninsured Associated Press lease, three GOP senators threat- be left without insurance under the House version. Senate leaders U INSIDE: The WASHINGTON ened to oppose a pivotal vote on the measure the House approved could use some of those savings to The Senate Republican health the proposal this week, enough Supreme Court is last month, the budget offi ce has attract moderate support by mak- care bill would leave 22 million to sink it unless Senate Majority allowing Trump to estimated. Trump has called ing Medicaid and other provisions more Americans uninsured in Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., forge ahead with a the House version approved last in their measure more generous, 2026 than under President Ba- can win over some of them or limited version of month “mean” and told Senate Re- though conservatives would prefer his travel ban. rack Obama’s health care law, the other GOP critics. The bill will fail publicans to approve legislation using that money to reduce federal Congressional Budget Offi ce esti- if just three of the 52 Republican A2 with more “heart.” defi cits. mated Monday, complicating GOP senators oppose it, an event that In good news for the GOP, the The White House lambasted leaders’ hopes of pushing the plan would deal a humiliating blow to The 22 million additional peo- budget offi ce said the Senate bill the nonpartisan budget office in through the chamber this week. -

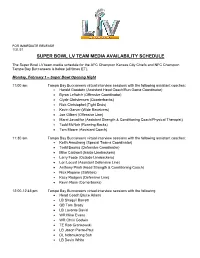

Super Bowl Lv Team Media Availability Schedule

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 1/31/21 SUPER BOWL LV TEAM MEDIA AVAILABILITY SCHEDULE The Super Bowl LV team media schedule for the AFC Champion Kansas City Chiefs and NFC Champion Tampa Bay Buccaneers is below (all times ET). Monday, February 1 – Super Bowl Opening Night 11:00 am Tampa Bay Buccaneers virtual interview sessions with the following assistant coaches: • Harold Goodwin (Assistant Head Coach/Run Game Coordinator) • Byron Leftwich (Offensive Coordinator) • Clyde Christensen (Quarterbacks) • Rick Christophel (Tight Ends) • Kevin Garver (Wide Receivers) • Joe Gilbert (Offensive Line) • Maral Javadifar (Assistant Strength & Conditioning Coach/Physical Therapist) • Todd McNair (Running Backs) • Tom Moore (Assistant Coach) 11:30 am Tampa Bay Buccaneers virtual interview sessions with the following assistant coaches: • Keith Armstrong (Special Teams Coordinator) • Todd Bowles (Defensive Coordinator) • Mike Caldwell (Inside Linebackers) • Larry Foote (Outside Linebackers) • Lori Locust (Assistant Defensive Line) • Anthony Piroli (Head Strength & Conditioning Coach) • Nick Rapone (Safeties) • Kacy Rodgers (Defensive Line) • Kevin Ross (Cornerbacks) 12:00-12:45 pm Tampa Bay Buccaneers virtual interview sessions with the following: • Head Coach Bruce Arians • LB Shaquil Barrett • QB Tom Brady • LB Lavonte David • WR Mike Evans • WR Chris Godwin • TE Rob Gronkowski • LB Jason Pierre-Paul • DL Ndamukong Suh • LB Devin White 4:00-4:45 pm Kansas City Chiefs virtual interview sessions with the following: • Head Coach Andy Reid • DE Frank Clark • RB -

Sunday, December 16, 2018 • Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum • 5:20 P.M

PHILADELPHIA EAGLES 4 Greg Zuerlein ...................K Sunday, December 16, 2018 • Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum • 5:20 p.m. PT 1 Cameron Johnston ............. P 6 Johnny Hekker .................P 4 Jake Elliott .......................... K 10 Pharoh Cooper ............ WR 7 Nate Sudfeld ................... QB 11 KhaDarel Hodge .......... WR RAMS OFFENSE RAMS DEFENSE 9 Nick Foles ....................... QB 12 Brandin Cooks ............. WR WR 83 Josh Reynolds 11 KhaDarel Hodge DE 90 Michael Brockers 94 John Franklin-Myers 11 Carson Wentz ................. QB 14 Sean Mannion .............. QB TE 89 Tyler Higbee 81 Gerald Everett 82 Johnny Mundt NT 93 Ndamukong Suh 92 Tanzel Smart 69 Sebastian Joseph-Day 13 Nelson Agholor ...............WR 16 Jared Goff ..................... QB LT 77 Andrew Whitworth 70 Joseph Noteboom DT 99 Aaron Donald 95 Ethan Westbrooks 17 Alshon Jeffery .................WR 17 Robert Woods .............. WR LG 76 Rodger Saffold III WILL 56 Dante Fowler Jr. 96 Matt Longacre 45 Ogbonnia Okoronkwo 18 Shelton Gibson ...............WR 19 JoJo Natson ................. WR C 65 John Sullivan 55 Brian Allen OLB 50 Samson Ebukam 53 Justin Lawler 49 Trevon Young 19 Golden Tate ....................WR 20 Lamarcus Joyner ............S RG 66 Austin Blythe ILB 58 Cory Littleton 54 Bryce Hager 59 Micah Kiser 22 Sidney Jones ...................CB 21 Aqib Talib ...................... CB RT 79 Rob Havenstein ILB 26 Mark Barron 52 Ramik Wilson 24 Corey Graham ................... S 22 Marcus Peters .............. CB 27 Malcolm Jenkins ................ S WR 12 Brandin Cooks 19 JoJo Natson LCB 22 Marcus Peters 37 Sam Shields 31 Darious Williams 23 Nickell Robey-Coleman CB 28 Wendell Smallwood .........RB 17 Robert Woods 10 Pharoh Cooper 24 Blake Countess ............ DB WR RCB 32 Aqib Talib 32 Troy Hill 23 Nickell Robey-Coleman 29 Avonte Maddox ................CB 26 Mark Barron ...................LB QB 16 Jared Goff 14 Sean Mannion SS 43 John Johnson III 24 Blake Countess 32 Rasul Douglas ..................CB 30 Todd Gurley II .............. -

Head Coach Mike Shanahan Owns a 40-19 (.678) Presea- NFL Defensive Ranking

denver broncos 2008 weekly press release Preseason Game #4 • Denver (1-2) at Arizona (2-1) Friday, Aug. 29, 2008 • 7 p.m. MST UNIVERSITY OF PHOENIX STADIUM (65,000) • Glendale, Arizona Issue Date: Sunday, Aug. 24, 2008 MEDIA RELATIONS CONTACT INFORMATION BRONCOS WRAP UP PRESEASON AGAINST ARIZONA FOR FIFTH YEAR IN A ROW Jim Saccomano (303) 649-0572 [email protected] Patrick Smyth (303) 649-0536 [email protected] In their final tune-up before the regular season, the Denver Dave Gaylinn (303) 649-0512 [email protected] Broncos (1-2) close out the 2008 Rebecca Villanueva (303) 649-0598 [email protected] preseason on the road against the Erich Schubert (303) 649-0503 [email protected] Arizona Cardinals (2-1) on Friday. Kickoff at University of Phoenix WWW.DENVERBRONCOS.COM/MEDIAROOM Stadium is set for 7 p.m. MST, and the game will be televised locally on KCNC-TV (CBS 4). The Denver Broncos have a media-only Web site, which was creat- The Broncos will end their preseason against the Cardinals for the ed to assist accredited media in their coverage of the Broncos. By fifth consecutive year and travel to Arizona after losing 27-24 at going to www.DenverBroncos.com/Mediaroom, members of the home to Green Bay in their most recent action on Aug. 22. Denver press will find complete statistical packages, press releases, rosters, starters played only the first two quarters, helping the club to a 17- updated bios, transcripts, injury reports, game recaps, news clippings, 13 halftime lead and scoring on all three possessions while limiting the Packers to 31 rushing yards on 12 attempts (2.6 avg.). -

Giants Qb Eli Manning, Rams Dt Aaron Donald & Cardinals K

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 12/16/15 http://twitter.com/nfl345 GIANTS QB ELI MANNING, RAMS DT AARON DONALD & CARDINALS K CHANDLER CATANZARO NAMED NFC PLAYERS OF WEEK 14 Quarterback ELI MANNING of the New York Giants, defensive tackle AARON DONALD of the St. Louis Rams and kicker CHANDLER CATANZARO of the Arizona Cardinals are the NFC Offensive, Defensive and Special Teams Players of the Week for games played the 14th week of the 2015 season (December 10, 13-14), the NFL announced today. OFFENSE: QB ELI MANNING, NEW YORK GIANTS Manning completed 27 of 31 passes (career-high 87.1 percent) for 337 yards with four touchdowns and no interceptions for a career-best 151.5 passer rating in the Giants’ 31-24 win at Miami. Manning’s 87.1 completion percentage is the highest by a Giants quarterback in a regular-season game (minimum 20 attempts) and the second-best mark in franchise history behind PHIL SIMMS’ 88.0 completion percentage (22 of 25) in Super Bowl XXI. He is the first Giants quarterback to have a passer rating of at least 150 in a game since 2002 (KERRY COLLINS, 158.3 on December 22). Manning threw touchdown passes to ODELL BECKHAM JR. (84 and six yards), RUEBEN RANDLE (six yards) and WILL TYE (five yards). Manning’s 84-yard touchdown pass to Beckham with 11:13 remaining in the fourth quarter broke a 24-24 tie and proved to be the game-winning score. He has six touchdown passes of at least 50 yards this season, the most in the NFL. -

Big 12 Conference Schools Raise Nine-Year NFL Draft Totals to 277 Alumni Through 2003

Big 12 Conference Schools Raise Nine-Year NFL Draft Totals to 277 Alumni Through 2003 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Apr. 26, 2003 DALLAS—Big 12 Conference teams had 10 of the first 62 selections in the 35th annual NFL “common” draft (67th overall) Saturday and added a total of 13 for the opening day. The first-day tallies in the 2003 NFL draft brought the number Big 12 standouts taken from 1995-03 to 277. Over 90 Big 12 alumni signed free agent contracts after the 2000-02 drafts, and three of the first 13 standouts (six total in the first round) in the 2003 draft were Kansas State CB Terence Newman (fifth draftee), Oklahoma State DE Kevin Williams (ninth) Texas A&M DT Ty Warren (13th). Last year three Big 12 standouts were selected in the top eight choices (four of the initial 21), and the 2000 draft included three alumni from this conference in the first 20. Colorado, Nebraska and Florida State paced all schools nationally in the 1995-97 era with 21 NFL draft choices apiece. Eleven Big 12 schools also had at least one youngster chosen in the eight-round draft during 1998. Over the last six (1998-03) NFL postings, there were 73 Big 12 Conference selections among the Top 100. There were 217 Big 12 schools’ grid representatives on 2002 NFL opening day rosters from all 12 members after 297 standouts from league members in ’02 entered NFL training camps—both all-time highs for the league. Nebraska (35 alumni) was third among all Division I-A schools in 2002 opening day roster men in the highest professional football configuration while Texas A&M (30) was among the Top Six in total NFL alumni last autumn. -

HEAD COACHES MOST COACHING WINS Name Years W L T Pct Bowl Wins NATIONAL COACH of the YEAR D

HEAD COACHES MOST COACHING WINS Name Years W L T Pct Bowl Wins NATIONAL COACH OF THE YEAR D. C. Walker 1937-50 (14) 77 51 6 .597 1 (‘46 Gator) Jim Grobe 2001-13 (13) 77 82 0 .484 3 (‘02 Seattle, ‘07 Meineke, ‘08 EagleBank) Dave Clawson 2014-pres. (6) 36 40 0 .474 3 (‘16 Military, ‘17 Belk, ‘18 Birmingham) Bill Dooley 1987-92 (6) 29 36 2 .448 1 (‘92 Independence) Jim Caldwell 1993-00 (8) 26 63 0 .292 1 (‘99 Aloha) Al Groh 1981-86 (6) 26 40 0 .394 LONGEST TENURES Name Years W L T Pct Bowl Games JIM GROBE D. C. Walker 1937-50 (14) 77 51 6 .597 2 (‘46 Gator, ‘49 Dixie) 2006 Jim Grobe 2001-13 (13) 77 82 0 .484 5 (‘02 Seattle, ‘07 FedEx Orange, ‘07 Meineke, ‘08 EagleBank, ‘11 Music City) American Football Coaches Associ- Jim Caldwell 1993-00 (8) 26 63 0 .292 1 (‘99 Aloha) ation Dave Clawson 2014-pres. (6) 36 40 0 .474 4 (‘16 Military, ‘17 Belk, ‘18 Birmingham, ‘19 Pinstripe) Associated Press Al Groh 1981-86 (6) 26 40 0 .394 Bobby Dodd Foundation Bill Dooley 1987-92 (6) 29 36 2 .448 1 (‘92 Independence) CBS Sportsline Sporting News OVERALL RECORD ACC RECORD Name Years W L T Pct W L T Pct W. C. Dowd* (Wake Forest ‘89) 1888 (1) 1 0 0 1.000 W. C. Riddick (Lehigh ‘90) 1889 (1) 3 3 0 .500 W. E. Sikes (Wake Forest ‘91) 1891-93 (3) 6 2 1 .722 Unknown 1895 (1) 0 0 1 .500 JOHN MACKOVIC A. -

Mike Clay's 2020 NFL Projection Guide

Mike Clay's 2020 NFL Projection Guide Updated: 9/10/2020 Glossary: Page 2-33: Team Projections Page 34-44: QB, RB, WR and TE projections Page 45-48: Category Leader projections Page 49: Projected standings, playoff teams and 2021 draft order Page 50: Projected Strength of Schedule Page 51: Unit Grades Page 52-61: Positional Unit Ranks Understanding the graphics: *The numbers shown are projections for the 2020 NFL regular season (Weeks 1-17). *Some columns may not seem to be adding up correctly, but this is simply a product of rounding. The totals you see are correct. *Looking for sortable projections by position or category? Check out the projections tab inside the ESPN Fantasy game. *'Team stat rankings' is where each team is projected to finish in the category that is shown. *'Unit Grades' is not related to fantasy football and is an objective ranking of each team at 10 key positions. The overall grades are weighted based on positional importance. The scale is 4.0 (best) to 0.1 (worst). A full rundown of Unit Grades can be found on page 51. *'Strength of Schedule Ranking' is based on 2020 rosters (not 2019 team record). '1' is easiest and '32' hardest. See the full list on page 50. *Note that prior to the official release of the NFL schedule (generally late April/early May), the schedule shown includes the correct opponents, but the order is random *Have a question? Contact Mike Clay on Twitter @MikeClayNFL 2020 Arizona Cardinals Projections QUARTERBACK PASSING RUSHING PPR DEFENSE WEEKLY SCORE PROJECTIONS Player Gm Att Comp Yds TD INT -

Washington Redskins Vs. San Francisco 49Ers October 20, 2019 | Landover, Md Game Release

X WEEK 7 WASHINGTON REDSKINS VS. SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS OCTOBER 20, 2019 | LANDOVER, MD GAME RELEASE 21300 Redskin Park Drive | Ashburn, Va. 20147 | 703.726.7000 @Redskins | www.Redskins.com | media.Redskins.com REGULAR SEASON - WEEK 7 WASHINGTON REDSKINS (1-5) VS SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS (5-0) Sunday, Oct. 20 | 1:00 p.m. ET FedExField (82,000) | Landover, Md. REDSKINS HOST NFC WEST GAME CENTER LEADING SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS SERIES HISTORY: 49ers lead the all-time series, 20-11-1 The Redskins will look to win their second consecutive game 49ers lead the all-time regular season when they host the undefeated San Francisco 49ers at FedexField on series, 17-10-1 Sunday. Kickoff is schedule for 1:00 p.m. Last meeting: Oct. 15, 2017 [26-24 WAS] The Redskins will be looking to secure their first win at FedexField since defeating the Dallas Cowboys, 20-17 in Week 7 of last season. TELEVISION: FOX They will also be looking to win consecutive games for the first time Chris Myers (play-by-play) since defeating the Carolina Panthers and Dallas Cowboys in Week 6 and Week 7 of the 2018 season, respectively. Daryl Johnston (analyst) The Redskins defense is coming off of a solid performance. They Laura Okmin (sideline) held the Miami Dolphins to 16 points along with only allowing 271 net yards. It was the least amount of yards allowed by the team this sea- RADIO: Redskins Radio Network son and the fewest since Week 15 of 2018. Larry Michael (play-by-play) During his weekly press conference with the local media on Mon- Chris Cooley (analysis) day, Interim Head Coach Bill Callahan praised the defense and spe- Rick “Doc” Walker (sidelines) cifically commented on the play of S Landon Collins and CB Quinton Dunbar. -

Sunday, December 20, 2020 4:05Pm | Los Angeles, Ca | Fox Week 15 | Game 14 Table of Contents Communications Center Jets in the Community

AT SUNDAY, DECEMBER 20, 2020 4:05PM | LOS ANGELES, CA | FOX WEEK 15 | GAME 14 TABLE OF CONTENTS COMMUNICATIONS CENTER JETS IN THE COMMUNITY .........................................................2 To assist in covering the team, the Jets have launched the New York Jets Communications Center (https://jets.1rmg.com/). A convenient, GAME INFO easy-to-use resource for media, the Communications Center will provide regularly updated access to: GAME NOTES .............................................................................2 • Schedules PLAYER NOTES ..........................................................................3 • Press Releases GAME PREVIEW .........................................................................9 • Jets in the Community News MATCHUP HISTORY .................................................................10 • Rosters & Pronunciations PROBABLE STARTERS ............................................................11 • Player & Coach Bios BY THE NUMBERS ...................................................................13 • New York Jets Media Guide STAFF BIOS • NFL Record & Fact Book CHRISTOPHER JOHNSON .......................................................15 • Transcripts JOE DOUGLAS ..........................................................................17 • Player/Coach Availability Video HYMIE ELHAI ............................................................................19 • Statistics ADAM GASE ..............................................................................20 • Game Releases COACHING