Alberto Caeiro's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Soundscape of Pier Paolo Pasolini's the Gospel According To

Nicola Martellozzo The Soundscape of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) ABSTRACT Il Vangelo secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to St. Matthew, IT/FR 1964), by the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, is one of the most interesting and widely acclaimed film representations of the life of Jesus. Its reception in the Catholic world has reflected the alternating fortunes of Pasolini himself, but over the years critics have come to fully appreciate its merits. While the director made faithful use of the dialogue in the Gospel, he constructed a new – but plausible – imagination, or “architecture of reality”, based on an intertextual code with intersecting pictorial, architectural, biblical and sound references. This essay aims in particular to employ a semiotic approach to an- alyse the musical motifs in the film and the way in which they convey precise meanings and values to the viewer about the figure and life of Jesus. Songs and musical compo- sitions are leitmotifs that punctuate the narrative, interweaving with the visual compo- nent to form a full-blown language in its own right. KEYWORDS Pier Paolo Pasolini; The Gospel According to St. Matthew; Musical Leitmotifs; Intertex- tuality; Audio-visual Syntax BIOGRAPHY Nicola Martellozzo graduated from the University of Bologna with a degree in cultural anthropology and ethnology. The author of an essay on the phenomenology of religious conversion (2015), he has presented papers at various specialist conferences (Italian Society of Medical Anthropology 2018; Italian Society of Cultural Anthropology 2018; Italian Society of Applied Anthropology; Italian National Professional Association of An- thropologist 2018). -

Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1968)

Christel Taillibert Théorème (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1968) Né en 1922, Pier Paolo Pasolini n'a cessé tout au long de sa vie de fustiger la société, ses conservatismes, ses hypocrisies et ses impostures. A la fois poète, essayiste, romancier et cinéaste, son art sera avant tout l'expression d'un être en souffrance, en rage contre un système dans lequel il ne se reconnaîtra jamais et qui jamais ne l'acceptera. De remous en véritables scandales, aucun de ses films ne laisse indifférent. Que ce soit en termes moraux, religieux ou politiques, Pasolini endure tout au long de sa carrière les foudres de ses - nombreux - détracteurs. Théorème, œuvre polysémique signée en 1968, est particulièrement symptomatique des passions que ses films étaient capables de déchaîner à l'époque. Générique Scénario, dialogue, réalisation : Pier Paolo Pasolini D'après le roman de Pier Paolo Pasolini, "Teorema" (Garzanti Editore, 1968) Interprétation : Terence Stamp (le visiteur), Massimo Girotti (Paolo, le père), Silvana Mangano (Lucia, la mère), Anne Wiazemsky (Odetta, la fille), Andres José Cruz (Pietro, le fils), Laura Betti (Emilia, la servante), Ninetto Davoli (Angiolino, le messager), Susanna Pasolini (la paysanne) Image : Giuseppe Ruzzolini (Eastmancolor) Décors : Luciano Puccini Costumes : Marcella De Machis Effets spéciaux : Goffredo Roccheti Montage : Nino Baragli Musique : Ennio Morricone et extraits du Requiem de Mozart Production : Aetos Film Producteurs : Franco Rossellini, Manolo Bolognini Directeur de production : Paolo Frasca Distribution : Coline / Planfilm Durée : 98 mn Résumé Un jeune homme aussi charmeur que silencieux débarque un beau jour dans une famille bourgeoise de Milan. Tour à tour, tous les occupants de la maison se laissent séduire - intellectuellement comme physiquement - par l'étrange visiteur. -

Moma and LUCE CINECITTÀ CELEBRATE the ENDURING INFLUENCE of ITALIAN FILMMAKER PIER PAOLO PASOLINI with a COMPREHENSIVE RETROSPECTIVE of HIS CINEMATIC WORKS

MoMA AND LUCE CINECITTÀ CELEBRATE THE ENDURING INFLUENCE OF ITALIAN FILMMAKER PIER PAOLO PASOLINI WITH A COMPREHENSIVE RETROSPECTIVE OF HIS CINEMATIC WORKS Accompanying Events include an Evening of Recital at MoMA; Programs of Performances and Film Installations at MoMA PS1; a Roundtable Discussion, Book Launch and Seminar, and Gallery Show in New York Pier Paolo Pasolini December 13, 2012–January 5, 2013 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, December 12, 2012—The Museum of Modern Art, Luce Cinecittà, and Fondo Pier Paolo Pasolini/Cineteca di Bologna present Pier Paolo Pasolini, a full retrospective celebrating the filmmaker’s cinematic output, from December 13, 2012 through January 5, 2013, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters. Pasolini’s film legacy is distinguished by an unerring eye for cinematic composition and tone, and a stylistic ease within a variety of genres—many of which he reworked to his own purposes, and all of which he invested with his distinctive touch. Yet, it is Pasolini’s unique genius for creating images that evoke the inner truths of his own brief life that truly distinguish his films. This comprehensive retrospective presents Pasolini’s celebrated films with newly struck prints by Luce Cinecittà after a careful work of two years, many shown in recently restored versions. The exhibition is organized by Jytte Jensen, Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art, and by Camilla Cormanni and Paola Ruggiero, Luce Cinecittà; with Roberto Chiesi, Fondo Pier Paolo Pasolini/Cineteca di Bologna; and Graziella Chiarcossi. Pasolini’s (b. Bologna, 1922-1975) cinematic works roughly correspond to four periods in the socially and politically committed artist’s life. -

Pier Paolo Pasolini: the GOSPEL ACCORDING to ST. MATTHEW

October 9, 2018 (XXXVII:7) Pier Paolo Pasolini: THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO ST. MATTHEW (1964, 137 min.) Online versions of The Goldenrod Handouts have color images & hot links: http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html DIRECTED BY Pier Paolo Pasolini WRITTEN BY Pier Paolo Pasolini PRODUCED BY Alfredo Bini MUSIC Luis Bacalov CINEMATOGRAPHY Tonino Delli Colli EDITING Nino Baragli PRODUCTION DESIGN Luigi Scaccianoce SET DECORATION Andrea Fantacci COSTUME DESIGN Danilo Donati MAKEUP Marcello Ceccarelli (makeup artist), Lamberto Marini (assistant makeup artist), Mimma Pomilia (hair stylist) ART DEPARTMENT Dante Ferretti SOUND Fausto Ancillai (sound mixer), Mario Del Pezzo (sound) VISUAL EFFECTS Ettore Catalucci COSTUME AND WARDROBE Piero Cicoletti (assistant Renato Terra...Un indemoniato costumer), Piero Farani (wardrobe) Eliseo Boschi...Giuseppe D'Arimatea Natalia Ginzburg...Maria di Betania CAST Enrique Irazoqui...Cristo PIER PAOLO PASOLINI (b. March 5, 1922 in Bologna, Margherita Caruso...Maria (giovane) Emilia-Romagna, Italy—d. November 2, 1975 (age 53) in Ostia, Susanna Pasolini...Maria (vecchia) Rome, Lazio, Italy) was published poet at 19 and had already Marcello Morante...Giuseppe written numerous novels and essays before his first screenplay in Mario Socrate...Giovanni Battista 1954. His first film Accattone (1961) was based on his own Settimio Di Porto...Pietro novel. He was arrested in 1962 when his contribution to Alfonso Gatto...Andrea Ro.Go.Pa.G. (1963) was considered blasphemous. The original Luigi Barbini...Giacomo Italian title of The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964), a Giacomo Morante...Giovanni realistic, stripped-down presentation of the life of Christ, Il Giorgio Agamben...Filippo vangelo secondo Matteo, pointedly omitted “Saint” in St. -

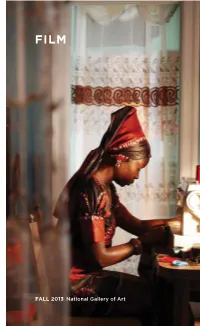

National Gallery of Art Fall 2013 Film Program

FILM FALL 2013 National Gallery of Art 11 Art Films and Events 18 The Play’s the Thing: Václav Havel, Art and Politics 22 Richard Wagner Revisited 25 American Originals Now: Moyra Davey 27 Pier Paolo Pasolini 32 Réalité Tales: Young French Cinema Mamma Roma p. 32 nga.gov/film cover: Mother of George p. 12 Unless otherwise noted, films are screened in the East Fall 2013 celebrates a rich history and vibrant new Building Auditorium, Fourth Street and Pennsylvania cinema through area premieres, in-person presentations, Avenue NW. Works are presented in original formats, and unique retrospectives. The influence and legacy of and seating is on a first-come, first-seated bases. Doors two of Europe’s most distinguished twentieth-century open thirty minutes before each show and programs artistic and political figures is explored in two programs. are subject to change. First, The Play’s the Thing: Václav Havel, Art and Politics focuses on the playwright-statesman’s long-standing For more information, e-mail [email protected], relationships with Prague’s Theatre on the Balustrade call (202) 842-6799, or visit nga.gov/film. and with visionary directors of the Czech New Wave. Second, a retrospective of the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922–1975) is offered following the 90th anniversary of his birth last year. Richard Wagner Revisited includes lec- tures and screenings that explore the composer’s lasting significance in the arts, while Réalité Tales: Young French Cinema introduces Washington audiences to films associ- ated with the contemporary Paris-based alliance known as Association du Cinéma Indépendant pour sa Diffusion (ACID). -

Contrasting Corporealities in Pasolini's La Ricotta Jill Murphy

1 Dark Fragments: Contrasting Corporealities in Pasolini’s La ricotta Jill Murphy, University College Cork Abstract: The short film La ricotta (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1963) tells the story of Stracci, an extra working on a film of the life of Christ, which is presented in part via tableaux vivants of Mannerist paintings. Pasolini’s film is replete with formal, stylistic and narrative binaries. In this article, I examine a particularly emphatic binary in the film in the form of the abstract, ethereal corporeality of the Mannerist paintings versus the raw and bawdy corporeality of Stracci. I show that through the reenactment of the paintings and their literal embodiment, Pasolini creates a rapprochement and, ultimately, a reversal between the divine forms created by the Mannerists and Stracci’s unremitting immanence, which, I argue, is allied to the carnivalesque and the cinematic body of Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp. I examine how Pasolini gradually deposes the Mannerists, and thus the art-historical excesses and erotic compulsion he feels towards the crucifixion, substituting in their place the corporeal form of Stracci in all its baseness and profanity. Introduction The corporeal—the quality and materiality of the body—is a driving force that accompanies more formal considerations throughout Pier Paolo Pasolini’s cinematographic work. From the physicalities of Accattone (1961) and Mamma Roma (1962), through the celebration of the carnivalesque and the sexual in the “Trilogia della vita” films, to the corporeal transgressions of Pigsty (Porcile, 1969) and Salò, or the 120 days of Sodom (Salò, o le 120 giornate di Sodoma, 1975), Pasolini is consistently guided by a deep-rooted sense of the physical in a range of guises. -

The Body of the Actor: Notes on the Relationship Between the Body And

https://doi.org/10.37050/ci-06_05 AGNESE GRIECO The Body of the Actor Notes on the Relationship between the Body and Acting in Pasolini’s Cinema CITE AS: Agnese Grieco, ‘The Body of the Actor: Notes on the Relationship between the Body and Acting in Pasolini’s Cinema’, in The Scandal of Self-Contradiction: Pasolini’s Multistable Subjectivities, Geographies, Traditions, ed. by Luca Di Blasi, Manuele Gragnolati, and Christoph F. E. Holzhey, Cultural Inquiry, 6 (Vienna: Turia + Kant, 2012), pp. 85–103 <https://doi.org/10.37050/ci-06_05> The Scandal of Self-Contradiction: Pasolini’s RIGHTS STATEMENT: Multistable Subjectivities, Geographies, Tradi- tions, ed. by Luca Di Blasi, Manuele Gragnolati, and Christoph F. E. Holzhey, Cultural Inquiry, © by the author(s) 6 (Vienna: Turia + Kant, 2012), pp. 85–103 This version is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED AS: Identical except for DOI prefix 10.25620 ABSTRACT: What is the role or the function of the actor in Pasolini’s cinema? I shall try to put this very general and generic question in another way: how can we define, overall, the particular physiognomy of a Pasolini actor? There are undoubtedly some particular characteristics, but what are they exactly? The ICI Berlin Repository is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the dissemination of scientific research documents related to the ICI Berlin, whether they are originally published by ICI Berlin or elsewhere. Unless noted otherwise, the documents are made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.o International License, which means that you are free to share and adapt the material, provided you give appropriate credit, indicate any changes, and distribute under the same license. -

Pressbook La Rabbia Di Pasolini ITALIANO Definitivox

Istituto Luce Cineteca di Bologna Gruppo Editoriale Minerva RaroVideo presentano LA RABBIA DI PASOLINI Ipotesi di ricostruzione della versione originale del film Realizzazione di Giuseppe Bertolucci da un’idea di Tatti Sanguineti Una distribuzione ISTITUTO LUCE LA RABBIA DI PASOLINI Ipotesi di ricostruzione della versione originale del film. 1963 . I cinegiornali Mondo Libero di Gastone Ferranti e i materiali reperiti in Cecoslovacchia, Unione Sovietica e Inghilterra diventano, per Pier Paolo Pasolini, la base per dare vita ad un’analisi lirica e polemica dei fenomeni e dei conflitti sociali e politici del mondo moderno, dalla Guerra Fredda al Miracolo economico, con un commento diviso fra una “voce in poesia” (Giorgio Bassani) ed una “voce in prosa” (Renato Guttuso). Mentre Pasolini è al lavoro in moviola, il produttore, forse per scrupoli politici o forse per motivazioni commerciali, decide di trasformare il film in un’opera a quattro mani, affidandone una parte a Giovannino Guareschi, secondo lo schema giornalistico del “visto da destra visto da sinistra”. Pasolini reagisce con irritazione a quella coabitazione forzata, ma alla fine accetta e rinuncia alla prima parte del suo film per lasciare spazio all’episodio di Guareschi. 2008 . Ci sembrava interessante (e una forma di risarcimento dovuto) provare a restituire, dopo tanti anni all’opera di Pasolini i connotati dell’originale. Partendo dal testo del poeta e dalla collezione di Mondo libero abbiamo dunque lavorato alla ricostruzione (o meglio alla “simulazione”) di quella prima parte mancante e la presentiamo, naturalmente con beneficio di inventario, al pubblico di oggi. “Perchè la nostra vita è domata dalla scontentezza, dall’angoscia, dalla paura della guerra?”. -

Pier Paolo Pasolini: a City Wide Celebration of His Genius Published on Iitaly.Org (

Pier Paolo Pasolini: a City Wide Celebration of His Genius Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Pier Paolo Pasolini: a City Wide Celebration of His Genius Natasha Lerdera (December 19, 2012) MoMA and Cinecittà Luce celebrate the enduring influence of Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini with a comprehensive retrospective of his cinematic works. The program is accompanied by side events Retrospective @ MoMA: December 13, 2012–January 5, 2013. More than two decades after its 1990 retrospective of Pier Paolo Pasolini, MoMA once again joins with Cinecittà Luce and Fondo Pier Paolo Pasolini/Cineteca di Bologna to present a full retrospective of Pasolini’s cinematic output. Many of these celebrated films will be shown in recently restored versions, and all are presented in newly struck prints. Much of this painstaking restoration work was performed by Cineteca di Bologna, Page 1 of 6 Pier Paolo Pasolini: a City Wide Celebration of His Genius Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) alongside several of Pasolini’s former collaborators. Pasolini’s cinematic legacy is distinguished by an unerring eye for cinematic composition and tone, and a stylistic ease within a variety of genres—many of which he reworked to his own purposes, and all of which he invested with his distinctive touch. Yet it is Pasolini’s unique genius for creating images that evoke the inner truths of his own brief life that truly sets his films apart—and entices new generations of cinephiles to explore his work. Pasolini’s cinematic works roughly correspond to four periods in the socially and politically committed artist’s life. -

A Revaluation of Pasolini's Salò

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 4 (2002) Issue 1 Article 2 A Revaluation of Pasolini's Salò A. Robert Lauer University of Oklahoma Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Lauer, A. Robert. "A Revaluation of Pasolini's Salò." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 4.1 (2002): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1141> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 2123 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

A “Desperate Vitality”. Tableaux Vivants in the Work of Pasolini and Ontani (1963-74)

ANNA MECUGNI A “desperate vitality”. Tableaux vivants in the work of Pasolini and Ontani (1963-74) I am a force of the Past. Only tradition is my love. I come from the ruins, the churches, the altarpieces, the villages abandoned on the Apennines, the Alpine foothills where my brothers lived. I rove the Tuscolana like a madman, or the Appia like a dog without a master. Or I look at the twilights, the mornings over Rome, Ciociaria, the world, like the first acts of post-history, which I witness, thanks to my date of birth, from the far edge of some buried age... And I, adult fetus, more modern than all the moderns, roam in search of brothers that are no more. Pier Paolo Pasolini, “10 giugno 1962”, Mamma Roma1 This essay focuses on four key works by Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-75) and Luigi Ontani (b. 1943) that involve tableaux vivants after sixteenth- and seventeenth-century paintings held in Italian churches and museums: Pasolini’s short film La ricotta (1963), and Ontani’s video Favola impropriata (1970-71) and two photographic works – La caduta dei ciechi d’après Brueghel and San Sebastiano nel bosco di Calvenzano (d’après Guido Reni) – also from circa 1970. In the 1960s and 1970s, several other Italian filmmakers and artists referenced past art in their work. Indeed, quotations and allusions to past art are characteristic of an idiosyncratic strain of Italian cinema and art that ran throughout the twentieth century. Ontani, however, stands out for his commitment to referencing past art through performance and impersonation, and his tableaux vivants have their most important precedent in Pasolini. -

Pasolini for the Future1

1 Pasolini for the Future Alessia Ricciardi Although “the future” may represent an ever hazier notion in the cultural and political imagination, public figures in Italy lately have invoked the concept with increasing frequency. Since their rift with the governing coalition led by Silvio Berlusconi, the members of Gianfranco Fini’s right-wing party have taken to calling themselves “the Futurists” (i futuristi) and have established the “MakeFuture Foundation” (Fondazione Farefuturo) to propagate their ideological views. Berlusconi himself recently has declared the intention of renaming his own party from “Let’s Go, Italy” (Forza Italia) to the more progressive-sounding “Forward, Italy” (Avanti Italia). At the same time, it appears that loss of hope regarding the future has become integral to our sense of our own late modernity in the field of critical thought. Among only the most current examples, the French anthropologist Marc Augé has announced that he is about to publish a book with the telling title Where Did the Future Go? (Ou est passé l’avenir?).2 The Italian strain of the attitude may be traced back at least to Giacomo Leopardi, who in the nineteenth century identified the narrowing down of life to the present tense as one of Italy’s most problematic tendencies, a trait that led him to characterize the nation as “without the prospect of a better sort of future, without occupation, without purpose.”3 Reflecting from the vantage point of the early twentieth century on Italy’s responsiveness to the weight of its long history from classical Rome to the present, Antonio Gramsci contended that among his compatriots the future always is passively expected “as it seems to be determined by the past” (2005, 201).