WSSG Newsletter34

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poland, May 2011

Woodpeckers, Waders and Warblers: North-eastern Poland, 12-17th May Participants: Ian Reid and Tom Bedford North-eastern Poland had been on my list of places to go ever since Bill Oddie’s second series went there and he was guided around by Marek Borkowski to see goodies such as Aquatic Warbler and Great Snipe. Finally in ’11 I decided it was high time I went and I was delighted when Tom showed enthusiasm for joining me. In fact having set the ball rolling, choosing the dates, sorting out guides, and pricing flights, I then ended up in a very busy period at work and it was Tom took care of most of the remaining logistics. It is possible to do such a trip rather cheaper than we did, but we opted for the convenience of Heathrow and took BA to Warsaw at a cost of approx. £150 each. Car hire, booked through carhire3000.com was a Toyota Yaris with Thrifty, and once we had added a second driver came to about £200 for 6 days. We booked guides through Lukasz Masurek’s site wildpoland.com for the evening of 12th (for Pygmy Owl), 8 hours on 13th (Woodpeckers and the Strict Reserve), and the evening of 13th (Great Snipe). Arek Szmyura, mentioned in many trip reports was our guide for the first two, and his son Mateusz took us to the Great Snipe lek. Prices have gone up a lot since the reports I read from ’09. The Pygmy Owl trip cost 90euros, Arek’s services for 8 hours on 13th was 150euros, and the Great Snipe trip was also 90euros. -

Bird Studies Overview

Chapter 7. Bird Studies Overview teigerwald Lake National Wildlife Refuge provides a variety of habitats for many species of birds. Thousands of breeding birds rely on the resources of the refuge to Srest, eat, and raise their young. In addition, the refuge supports wetlands that are vital to the survival of migratory birds. The activities that follow offer an excellent opportunity for students to learn about and to observe the different species of birds — their behaviors and adaptations to the habitats on the refuge. Background The actively managed refuge wetlands and grasslands, when combined with the natural floodplain vegetative communities, provide habitat that supports over 200 species of birds. Hundreds of thousands of birds migrate along the lower Columbia River every year. The refuge hosts thousands of migratory birds that fly thousands of miles from their breeding grounds in Arctic Canada and Alaska to their wintering grounds in Baja California or South America, a route known as the Pacific Flyway. The few remaining areas of wetland habitat along the lower Columbia River are vital to the flyway. Some birds spend their winter on refuge wetlands, returning north to nest; some nest here but migrate to milder climates in the south for the winter; and some do not migrate at all but remain in the area as permanent residents. Several of the songbirds found in the summer spend our winters in Central and South America, migrating thousands of miles annually between their summer and winter habitats. Birds using the refuge are specifically adapted to the type of food they eat and the type of habitat they occupy (open water, freshwater wetland, field, riparian woodland, or upland woodland). -

Migration Phenology of Jack Snipe Lymnocryptes Minimus at an Irish Coastal Wetland

Migration phenology of Jack Snipe Lymnocryptes minimus at an Irish coastal wetland Tom Cooney 42 All Saint’s Road, Raheny, Dublin D05 C627 Corresponding author: [email protected] Keywords: Ireland, Jack Snipe, Lymnocryptes minimus , migration phenology Migration times of Jack Snipe Lymnocryptes minimus were monitored at North Bull Island in Dublin Bay during 2011/2012 to 2016/2017. Average arrival times in autumn centred on 2 October and average departure times in spring on 23 April. Although these results were site and habitat specific, they were similar to recent migration data for Ireland. While the time series examined for Ireland and Britain were of different lengths, migration times were extraordinarily similar. The average autumn arrival date for Ireland as a whole was 16 September while that for Britain was 23 September, and departure times in spring for Ireland centred on 30 April, one day later than in Britain. The close agreement suggests that migration times across both islands possibly occur synchronously. Other recently generated data for Ireland provides tantalising evidence that passage migration may take place and that Jack Snipe could be more frequent in upland areas than previously suspected. In both instances greater clarity will only be possible through increased observer effort and higher detection rates of this enigmatic species. Introduction Britain, but not in Ireland (Smiddy 2002). In winter, Jack Snipe appear to be widely but thinly distributed across much of Jack Snipe Lymnocryptes minimus are difficult to detect in Ireland with highest densities in counties along the west coast winter largely due to their solitary behaviour, nocturnal or (Balmer et al. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

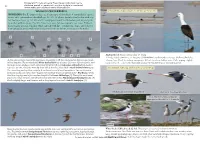

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

03/16/2020 9:21 Am

ACTION: Withdraw Proposed DATE: 03/16/2020 9:21 AM 1501:31-7-05 Seasons and limits on rail, common snipe (Wilson's snipe), woodcock, gallinules (common moorhens), teal, geese and mourning doves. (A) Throughout the state, it shall be unlawful for any person to hunt, kill, wound, take, or attempt to take, or to possess any of the migratory game birds specified in this rule except as provided in this rule or other rules of the Administrative Code. (1) It shall be unlawful for any person to hunt, take, or possess any rails except sora and Virginia, which may be hunted and taken from September 1, 20192020 through November 9, 20192020. (2) It shall be unlawful for any person to take or possess more than twenty-five rails singly or in the aggregate in one day, or to possess more than seventy-five rails singly or in the aggregate at anytime after the second day. (3) It shall be unlawful for any person to hunt, take, or possess common snipe (Wilson's snipe) at any time, except from September 1, 20192020 through November 26, 201924, 2020 and December 14, 201912, 2020 through January 2December 31, 2020. (4) It shall be unlawful for any person to hunt, take, or possess woodcock at any time, except from October 12, 201910, 2020 through November 25, 201923, 2020. (5) It shall be unlawful for any person to hunt or take rails, common snipe (Wilson's snipe), woodcock, or gallinules (common moorhens) at any time, except from sunrise to sunset daily during the open season. -

Growth and Development of Long-Billed Curlew Chicks

April 1973] General Notes 435 Pitelka and Donald L. Beaver critically read the manuscript. This work was con- ducted under the I.B.P. Analysis of Ecosystems-TundraProgram and supported by a grant to F. A. Pitelka from the National ScienceFoundation.--THo•rAs W. CUSTrR, Department o! Zoology and Museum o! Vertebrate Zoology, University o! California, Berkeley,California 94720. Accepted9 May 72. Growth and development of Long-billed Curlew chicks.--Compared with the altricial nestlings of passerinesand the semiprecocialyoung of gulls, few studies of the growth and developmentof the precocialchicks of the Charadrii have been made (Pettingill, 1970: 378). In Europe, yon Frisch (1958, 1959) describedthe develop- ment of behavior in 14 plovers and sandpipers. Davis (1943) and Nice (1962) have reported on the growth of Killdeer (Charadriusvociferus), Nice (1962) on the Spotted Sandpiper (Actiris macularia), and Webster (1942) on the growth and development of plumages in the Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani). Pettingill (1936) studiedthe atypical AmericanWoodcock (Philohelaminor). Among the curlews, Genus Numenius, only the Eurasian Curlew (N. arquata) has been studied (von Frisch, 1956). Becauseof the scant knowledgeabout the development of the youngin the Charadriiand the scarcityof informationon all aspectsof the breeding biology of the Long-billed Curlew (N. americanus) (Palmer, 1967), I believe that the following data on the growth and development of Long-billed Curlew chicks are relevant. I took four eggs,one being pipped, from a nest 10 miles west of Brigham City, Box Elder County, Utah, on 24 May 1966. One egg was preservedimmediately for additional study, the others I placed in a 4' X 3' X 2' cardboard box with a 60-watt lamp for warmth in a vacant room in my home until they hatched. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

View) from Be Sourced up Until the End of November to Try Collapsed Drains and Was Mostly Covered in and Limit Regrowth of Vegetation

Conservation Evidence (2006) 3, 79-80 www.ConservationEvidence.com The effectiveness of opening up rush patches on encouraging breeding common snipe Gallinago gallinago at Rogersceugh Farm, Campfield Marsh RSPB reserve, Cumbria, England Holton N. & Allcorn R.I. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire SG19 2GL, UK SUMMARY An area of improved grassland was dominated by rushes Juncus spp. and purple moor-grass Molinia caerulea . In order to try and attract breeding common snipe Gallinago gallinago , the rush was cut in 2003 with tractor mounted mowers and then grazed. In addition, 18 small scrapes were dug and higher water levels were maintained. The number of snipe increased from one nesting pair in 2003 to 11 nesting pairs in both 2004 and 2005. BACKGROUND Throughout the UK, common snipe Gallinago gallinago are undergoing a large population decline of between 25-49% in both breeding population and range over the last 25 years. Snipe feed by probing for invertebrates deep in soft, damp soil using their long bills. They also require wet marshy grassland areas with tussocks of taller vegetation for nesting. ACTION Figure 1 . All the rush on the improved grassland was cut with tractor mounted mowers. Study site: Rogersceugh Farm in Cumbria, north-west England, is a traditionally managed farm incorporating approximately 60 ha of waist high rush Juncus spp. and purple moor- reclaimed peatland. The RSPB purchased the grass Molinia caerulea . A breeding wader farm in order to raise water levels on the survey was carried out in 2003 prior to the adjacent raised mire whilst at the same time purchase of the farm by the RSPB. -

Review of the Conflict Between Migratory Birds and Electricity Power Grids in the African-Eurasian Region

CMS CONVENTION ON Distribution: General MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/Inf.10.38/ Rev.1 SPECIES 11 November 2011 Original: English TENTH MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Bergen, 20-25 November 2011 Agenda Item 19 REVIEW OF THE CONFLICT BETWEEN MIGRATORY BIRDS AND ELECTRICITY POWER GRIDS IN THE AFRICAN-EURASIAN REGION (Prepared by Bureau Waardenburg for AEWA and CMS) Pursuant to the recommendation of the 37 th Meeting of the Standing Committee, the AEWA and CMS Secretariats commissioned Bureau Waardenburg to undertake a review of the conflict between migratory birds and electricity power grids in the African-Eurasian region, as well as of available mitigation measures and their effectiveness. Their report is presented in this information document and an executive summary is also provided as document UNEP/CMS/Conf.10.29. A Resolution on power lines and migratory birds is also tabled for COP as UNEP/CMS/Resolution10.11. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. The Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) and the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) REVIEW OF THE CONFLICT BETWEEN MIGRATORY BIRDS AND ELECTRICITY POWER GRIDS IN THE AFRICAN-EURASIAN REGION Funded by AEWA’s cooperation-partner, RWE RR NSG, which has developed the method for fitting bird protection markings to overhead lines by helicopter. Produced by Bureau Waardenburg Boere Conservation Consultancy STRIX Ambiente e Inovação Endangered Wildlife Trust – Wildlife & Energy Program Compiled by: Hein Prinsen 1, Gerard Boere 2, Nadine Píres 3 & Jon Smallie 4. -

Fastest Migration Highest

GO!” Everyone knows birds can fly. ET’S But not everyone knows that “L certain birds are really, really good at it. Meet a few of these champions of the skies. Flying Acby Ellen eLambeth; art sby Dave Clegg! Highest You don’t have to be a lightweight to fly high. Just look at a Ruppell’s griffon vulture (left). One was recorded flying at an altitude of 36,000 feet. That’s as high as passenger planes fly! In fact, it’s so high that you would pass out from lack of oxygen if you weren’t inside a plane. How does the vulture manage? It has Fastest (on the level) Swifts are birds that have that name for good special blood cells that make a small amount reason: They’re speedy! The swiftest bird using its own of oxygen go a long way. flapping-wing power is the common swift of Europe, Asia, and Africa (below). It’s been clocked at nearly 70 miles per hour. That’s the speed limit for cars on some highways. Vroom-vroom! Fastest (in a dive) Fastest Migration With gravity helping out, a bird can pick up extra speed. Imagine taking a trip of about 4,200 And no bird can go faster than a peregrine falcon in a dive miles. Sure, you could easily do it in an airplane. after prey (right). In fact, no other animal on Earth can go as But a great snipe (right) did it on the wing in just fast as a peregrine: more than 200 miles per hour! three and a half days! That means it averaged about 60 miles The prey, by the way, is usually another bird, per hour during its migration between northern which the peregrine strikes in mid-air with its balled-up Europe and central Africa. -

Migration Timing, Routes, and Connectivity of Eurasian Woodcock Wintering in Britain and Ireland

Migration Timing, Routes, and Connectivity of Eurasian Woodcock Wintering in Britain and Ireland ANDREW N. HOODLESS,1 Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust, Burgate Manor, Fordingbridge, Hampshire SP6 1EF, UK CHRISTOPHER J. HEWARD, Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust, Burgate Manor, Fordingbridge, Hampshire SP6 1EF, UK ABSTRACT Migration represents a critical time in the annual cycle of Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola), with poten- tial consequences for individual fitness and survival. In October–December, Eurasian woodcock migrate from breeding grounds in northern Eurasia over thousands of kilometres to western Europe, returning in March–May. The species is widely hunted in Europe, with 2.3–3.5 million individuals shot per year; hence, an understanding of the timing of migra- tion and routes taken is an essential part of developing sustainable flyway management. Our aims were to determine the timing and migration routes of Eurasian woodcock wintering in Britain and Ireland, and to assess the degree of connec- tivity between breeding and wintering sites. We present data from 52 Eurasian woodcock fitted with satellite tags in late winter 2012–2016, which indicate that the timing of spring departure varied annually and was positively correlated with temperature, with a mean departure date of 26 March (± 1.4 days SE). Spring migration distances averaged 2,851 ± 165 km (SE), with individuals typically making 5 stopovers. The majority of our sample of tagged Eurasian woodcock migrated to breeding sites in northwestern Russia (54%), with smaller proportions breeding in Denmark, Scandinavia, and Finland (29%); Poland, Latvia, and Belarus (9.5%); and central Russia (7.5%). The accumulated migration routes of tagged individ- uals suggest a main flyway for Eurasian woodcock wintering in Britain and Ireland through Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany, and then dividing to pass through the countries immediately north and south of the Baltic Sea.