Uneasy Listening

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boyd Rice Is a Putz in My Book, but Examining His Politics, You'll Find a More Compelling and Compelled Point of View Than Many Other Cultural Commentators

Regarding Evil by Ross B. Cisneros B.F.A The Cooper Union School of Art, 2002 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN VISUAL STUDIES AT THE_____ __ ATMTSSACHUSETTS INSTRTUT MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOG OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2005 JUN 28 2005 c 2005 Ross B. Cisneros, All rights reserved. LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic ROTCH copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Degrtmei't Aehitecture '-M~y 6, 2005 Certified by: Krzy'sztof Wodiczko Professor of Visual Arts Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Ad6le Naud6 Santos Chair, Committee on Graduate Students Acting Head, Department of Architecture Dean, School of Architecture and Planning 2 REGARDING EVIL By ROSS B. CISNEROS Submitted to the Department of Architecture On May 6, 2005 in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Visual Studies ABSTRACT The transnational summit, Regarding Evil, was called to assembly with the simultaneous sounding of the trumps in six sites around the world, projected simulcast. In collaboration with the six individuals who were issued the instruments, each announced their particular state of emergency and converged at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with a seventh blast. Scotsman Kenneth Smith assumed the role of 7th piper. Artists and scholars of international reputation had been invited to present visual and discursive material confronting the elusive and immeasurable subject of Evil, its transpolitical behaviors, charismatic aesthetic, and viral disbursement in the vast enterprise of simulation, symbolic power, and catastrophe. -

Descent V 1999

w< >l F=Fli >w , ^ >< c Q. (5 (/) >< Q Q 3 ifl 1 u -i — — n 3 "0 3 ^ ?r S (11 • ii ir-ji I- ^ .*> a - i J The ajna Offensive is pro 1 ^ I <4 ( present a series of aui interpretations of visual / Recently the realization set in with me about my current surroundings and lack of inspirational environs, and the difference between those and newly rediscovered potentials. the self-limitations one imposes. since leaving europe it has been this way it seems, in general, the fountain of vision/creativity has been tapped a bit by a _ and shallow production outlook... it became clearer recently what was ULTRA fistic and characteristic expression and what wasn't. unfortunately, over the "ABANDONED"/ THIS LACK OF CREATIVE INFLUXLUX HAS SPILLED OVER TO MY WORK WITH THIS MAGAZINE, IT .AND FORGOTTEN' T SEVERAL NOT SO IMPORTANT (UPONON REFLECTION) IDEAS AND ATTITUDESATTITU CLOUDED OVER 7" OF MY WORK HERE, LUCKILY TYLER HAS KEPT•'-'•- THE- '- FIRE BURNING - HEART OF HANK YOU SO VERY MUCH MR. DAVIS. SO, THE DEATH ISSUE DO LLY HAVE IMPRESSIONS FROM HANS BELMER, MUCH TO DO WITH THE MAGAZINE ITSELF BUT IT'S RATHER A DOCUMENT OF PERSONAL LIMITED TO 300 COPIES ISSUES. AS I EMBARK AWAY FROM THE WEST COAST AGAIN FOR AN'T REALLY + 26 LETTERED AND SIGNED EDITIONS ENVISION WHAT IS NEXT FOR THIS PUBLICATION... OR OTHERWISE.... HER THAN ANNOUNCE OR $8 US/$10 OVERSEAS PREDICT THE NEXT MOVE AS WE HAVE IN THE PAST ;W NATURALLY THIS TIME, THE WAY IT SHOULD BE. IT'S ALWAYS A SLOW, PA IEND DESCRIBED IT) BUT MAYBE IT ALWAYS WAS SO BECAUSE VIOUS EXPECTATIONS. -

![HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8672/how-black-is-black-metal-journalismus-nachrichten-von-heute-488672.webp)

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] nachrichten von heute Kevin Coogan - Lords of Chaos (LOC), a recent book-length examination of the “Satanic” black metal music scene, is less concerned with sound than fury. Authors Michael Moynihan and Didrik Sederlind zero in on Norway, where a tiny clique of black metal musicians torched some churches in 1992. The church burners’ own place of worship was a small Oslo record store called Helvete (Hell). Helvete was run by the godfather of Norwegian black metal, 0ystein Aarseth (“Euronymous”, or “Prince of Death”), who first brought black metal to Norway with his group Mayhem and his Deathlike Silence record label. One early member of the movement, “Frost” from the band Satyricon, recalled his first visit to Helvete: I felt like this was the place I had always dreamed about being in. It was a kick in the back. The black painted walls, the bizarre fitted out with inverted crosses, weapons, candelabra etc. And then just the downright evil atmosphere...it was just perfect. Frost was also impressed at how talented Euronymous was in “bringing forth the evil in people – and bringing the right people together” and then dominating them. “With a scene ruled by the firm hand of Euronymous,” Frost reminisced, “one could not avoid a certain herd-mentality. There were strict codes for what was accept- ed.” Euronymous may have honed his dictatorial skills while a member of Red Ungdom (Red Youth), the youth wing of the Marxist/Leninist Communist Workers Party, a Stalinist/Maoist outfit that idolized Pol Pot. All who wanted to be part of black metal’s inner core “had to please the leader in one way or the other.” Yet to Frost, Euronymous’s control over the scene was precisely “what made it so special and obscure, creating a center of dark, evil energies and inspiration.” Lords of Chaos, however, is far less interested in Euronymous than in the man who killed him, Varg Vikemes from the one-man group Burzum. -

TAZ, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism.Pdf

T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey Autonomedia Anti-copyright, 1985, 1991. May be freely pirated & quoted-- the author & publisher, however, would like to be informed at: Autonomedia P. O. Box 568 Williamsburgh Station Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Book design & typesetting: Dave Mandl HTML version: Mike Morrison Printed in the United States of America Part 1 T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CHAOS: THE BROADSHEETS OF ONTOLOGICAL ANARCHISM was first published in 1985 by Grim Reaper Press of Weehawken, New Jersey; a later re-issue was published in Providence, Rhode Island, and this edition was pirated in Boulder, Colorado. Another edition was released by Verlag Golem of Providence in 1990, and pirated in Santa Cruz, California, by We Press. "The Temporary Autonomous Zone" was performed at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, and on WBAI-FM in New York City, in 1990. Thanx to the following publications, current and defunct, in which some of these pieces appeared (no doubt I've lost or forgotten many--sorry!): KAOS (London); Ganymede (London); Pan (Amsterdam); Popular Reality; Exquisite Corpse (also Stiffest of the Corpse, City Lights); Anarchy (Columbia, MO); Factsheet Five; Dharma Combat; OVO; City Lights Review; Rants and Incendiary Tracts (Amok); Apocalypse Culture (Amok); Mondo 2000; The Sporadical; Black Eye; Moorish Science Monitor; FEH!; Fag Rag; The Storm!; Panic (Chicago); Bolo Log (Zurich); Anathema; Seditious Delicious; Minor Problems (London); AQUA; Prakilpana. Also, thanx to the following individuals: Jim Fleming; James Koehnline; Sue Ann Harkey; Sharon Gannon; Dave Mandl; Bob Black; Robert Anton Wilson; William Burroughs; "P.M."; Joel Birroco; Adam Parfrey; Brett Rutherford; Jake Rabinowitz; Allen Ginsberg; Anne Waldman; Frank Torey; Andr Codrescu; Dave Crowbar; Ivan Stang; Nathaniel Tarn; Chris Funkhauser; Steve Englander; Alex Trotter. -

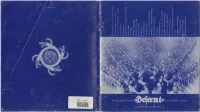

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO Mccormick 04 06 a Beginning, and an End 06 10 the Precursors: WILLIAM S

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO McCORMICK 04 06 A Beginning, and an End 06 10 The Precursors: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS 10 14 The Precursors: ANTON LaVEY 14 20 The Precursors: KENNETH ANGER 20 22 The Precursors: ROBERT WILLIAMS 22 30 The Precursors: CHARLES MANSON 30 38 The Precursors: GENESIS P-ORRIDGE 38 46 The Precursors: MONTE CAZAZZA 46 50 The Precursors: HARLEY FLANNAGAN / CRO-MAGS 50 54 Soundtrack to 1984: Rev. Jim Jones — The Last Supper 54 55 Soundtrack to 1984: PSYCHIC TV 55 56 Soundtrack to 1984: ANTON LaVEY et al - The Satanic Mass 56 57 Soundtrack to 1984: CHARLES MANSON - Lie 57 58 Soundtrack to 1984: LYDIA LUNCH 58 59 Soundtrack to 1984: FOETUS 59 60 Soundtrack to 1984: NON 60 61 Soundtrack to 1984: RADIO WEREWOLF 61 62 Soundtrack to 1984: WHITEHOUSE 62 63 Soundtrack to 1984: Skinned Alive 63 64 Soundtrack to 1984: MICHAEL MOYNIHAN 64 65 Soundtrack to 1984: GG ALLIN 65 66 Soundtrack to 1984: KING DIAMOND / CRO-MAGS show 66 67 Soundtrack to 1984: SWANS 67 68 JOE COLEMAN 68 76 LYDIA LUNCH 76 82 NICK ZEDD / THE UNDERGROUND FILM BULLETIN 82 88 RICHARD KERN / DEATHTRIP FILMS 88 94 J.G. THIRLWELL a.k.a. FOETUS 94 98 FRED BERGER / PROPAGANDA 98 106 JONATHAN SHAW 106 112 Killer Clowns 112 124 BOYD RICE/NON . 124 132 JOHN AES-NIHIL 132 138 NICKBOUGAS 138 144 ZEENA SCHRECK nee LaVEY 144 148 NIKOLAS SCHRECK / RADIO WEREWOLF 148 154 ADAM PARFREY / FERAL HOUSE 154 162 Your host, GEORGE PETROS 162 170 MICHAEL ANDROS 170 174 ROBERT N. -

December 2020 New Releases

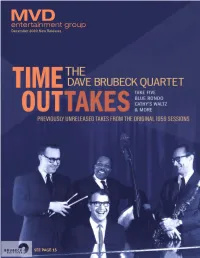

December 2020 New Releases SEE PAGE 15 what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 59 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 12 FEATURED RELEASES Video WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. THE DAVE BRUBECK THE RESIDENTS - 35 FEATURING MICK ROSSI - QUARTET - IN BETWEEN DREAMS: Film LIVE IN TOKYO TIME OUTTAKES LIVE IN SAN FRANCISCO Films & Docs 36 Faith & Family 56 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 57 Order Form 69 Deletions & Price Changes 65 TREMORS MANIAC A NIGHT IN CASABLANCA 800.888.0486 (2-DISC SPECIAL EDITION) 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 www.MVDb2b.com WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. BERT JANSCH - SUPERSUCKERS - FEATURING MICK ROSSI - BEST OF LIVE MOTHER FUCKERS BE TRIPPIN’ TIME OUT AND TAKE FIVE! LIVE IN TOKYO We could use a breather from what has been a most turbulent year, and with our December releases, we provide a respite with fantastic discoveries in the annals of cool jazz. THE DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET “TIME OUTTAKES” is an alternate version of the masterful TIME OUT 1959 LP, with the seven tracks heard for the first time in crisp, different versions with a bonus track and studio banter. The album’s “Take Five” is the biggest selling jazz single ever, and hearing this in different form is downright thrilling. On LP and CD. Also smooth jazz reigns supreme with a CD release of a newly discovered live performance from sax legend GEORGE COLEMAN. “IN BALTIMORE” is culled from a 1971 performance with detailed liner notes and rare photos. Kick Out the Jazz! Something else we could use is a release from oddball novelty song collector DR. -

La Mamelle and the Pic

1 Give Them the Picture: An Anthology 2 Give Them The PicTure An Anthology of La Mamelle and ART COM, 1975–1984 Liz Glass, Susannah Magers & Julian Myers, eds. Dedicated to Steven Leiber for instilling in us a passion for the archive. Contents 8 Give Them the Picture: 78 The Avant-Garde and the Open Work Images An Introduction of Art: Traditionalism and Performance Mark Levy 139 From the Pages of 11 The Mediated Performance La Mamelle and ART COM Susannah Magers 82 IMPROVIDEO: Interactive Broadcast Conceived as the New Direction of Subscription Television Interviews Anthology: 1975–1984 Gregory McKenna 188 From the White Space to the Airwaves: 17 La Mamelle: From the Pages: 87 Performing Post-Performancist An Interview with Nancy Frank Lifting Some Words: Some History Performance Part I Michele Fiedler David Highsmith Carl Loeffler 192 Organizational Memory: An Interview 19 Video Art and the Ultimate Cliché 92 Performing Post-Performancist with Darlene Tong Darryl Sapien Performance Part II The Curatorial Practice Class Carl Loeffler 21 Eleanor Antin: An interview by mail Mary Stofflet 96 Performing Post-Performancist 196 Contributor Biographies Performance Part III 25 Tom Marioni, Director of the Carl Loeffler 199 Index of Images Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA), San Francisco, in Conversation 100 Performing Post-Performancist Carl Loeffler Performance or The Televisionist Performing Televisionism 33 Chronology Carl Loeffler Linda Montano 104 Talking Back to Television 35 An Identity Transfer with Joseph Beuys Anne Milne Clive Robertson -

Wegart Novinky Marec - Apríl 2008

WEGART NOVINKY MAREC - APRÍL 2008 The Kills – Midnight Boom (Domino) Doposia ľ najkonzistentnejší, najpestrejší a najtvorivejší album The Kills. Dôkaz, že váše ň a kreativita sú nadovšetko. - All Music Guide Je to album minimálne porovnate ľný s ich predchádzajúcimi nahrávkami, v niektorých oh ľadoch lepší - a ak vás dostali svojím kúzlom v minulosti, bu ďte si istí, že im úplne prepadnete aj tentokrát. - Drowned In Sound Nielenže The Kills vytvorili zna čkový rock'n'rollový album, je to jeden z tých, ktorý s neprístojnou ľahkos ťou bude odoláva ť nástrahám času. - Dot Music Formát: CD Cena: 550 Sk Kat. č.: WIGCD184 EAN: 5034202018421 Ďalšie tituly The Kills na sklade: No Wow CD+DVD 650 Sk No Wow CD 550 Sk Keep On Your Mean Side CD 550 Sk Black Roster CDEP 280 Sk Love Is A Deserter CDS 230 Sk Sons And Daughters – This Gift (Domino) Nový album glasgowskej štvorice je mixom zakaleného pôvabu šes ťdesiatych rokov a post- miléniovej kultúry celebrít, kultových filmov a literárnej klasiky. Kapela prekro čila elegantne vytvorené hranice svojich predošlých nahrávok novou ambíciou a plnos ťou zvuku. Produkoval nekompromisný producent a bývalý gitarista skupiny Suede Bernard Butler. Za posledných pä ť rokov si kapela vytvorila jednozna čný zvuk, imidž a históriu, inšpirovaná čistou silou country, bluesu a folku. Ich fanúšikmi sa stali Nick Cave, Franz Ferdinand a kritici, ktorí ozna čili Sons And Daughters ako jedine čnú skupinu vybraného vkusu a názoru. Obsahuje live CD. Formát: 2CD Cena: 590 Sk Kat. č.: WIGCD197 EAN: 5034202019725 Ďalšie tituly Sons & Daughters na sklade: The Repulsion Box CD 490 Sk Stephen Malkmus and the Jicks – Real Emotional Trash (Domino) Štvrtý album ex-frontmana Pavement. -

Death in June Live in New York Mp3, Flac, Wma

Death In June Live In New York mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Live In New York Country: US Released: 2006 Style: Acoustic, Neofolk MP3 version RAR size: 1463 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1988 mb WMA version RAR size: 1946 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 701 Other Formats: MP3 RA TTA VOC MPC MOD AIFF Tracklist 1 Ku Ku Ku 2:54 2 He's Disabled 2:50 3 Little Black Angel 3:15 4 We Said Destroy II 3:33 5 Rocking Horse Night 3:11 6 Disappear In Every Way 2:59 7 Torture By Roses 2:35 8 All Pigs Must Die 2:25 9 Hullo Angel 2:10 10 Omen Filled Season 2:32 11 She Said Destroy 3:16 12 Smashed To Bits (In The Peace Of The Night) 3:17 13 Come Before Christ And Murder Love 2:24 14 Tick Tock 2:27 15 Fall Apart 2:40 16 Leper Lord 1:28 17 To Drown A Rose 3:21 18 Hollows Of Devotion 3:17 19 Golden Wedding Of Sorrow 3:06 20 Death Of The West 2:02 21 Symbols Of The Sun 2:49 22 Runes And Men 2:24 23 Kameradschaft 3:11 24 The Honour Of Silence 2:37 25 Giddy Giddy Carousel 1:40 26 Luther's Army 3:57 27 Fields Of Rape 2:54 28 Heaven Street 4:58 29 The Enemy Within 3:30 Credits Edited By, Photography – Nyle Cavazos Garcia Engineer [Live Sound Engineer] – Darryl Hell Guitar, Vocals – Douglas P.* Percussion – John Murphy Producer – James Elenidis, Jane Elizabeth Producer [Audio Post Production], Mastered By – Flam* Recorded By – Guy Gustafson Notes Filmed and recorded on November 10, 2002, at Walker Stage in New York. -

Rage in Eden Records, Po Box 17, 78-210 Bialogard 2, Poland [email protected]

RAGE IN EDEN RECORDS, PO BOX 17, 78-210 BIALOGARD 2, POLAND [email protected], WWW.RAGEINEDEN.ORG Artist Title Label HAUSCHKA ROOM TO EXPAND 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX BLUE NOTEBOOKS, THE 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX SONGS FROM BEFORE 130701/FAT CAT CD ASCENSION OF THE WAT NUMINOSUM 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY COVER UP 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS LTD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE BLOOD 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE DUB YA 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD PRONG POWER OF THE DAMAGER 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKED AND LOADED 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKTAIL MIXXX 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD BERNOCCHI, ERALDO/FE MANUAL 21ST RECORDS CD BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FA BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FAMILY 21ST RECORDS CD FLOWERS OF NOW INTUITIVE MUSIC LIVE IN COLOGNE 21ST RECORDS CD LOST SIGNAL EVISCERATE 23DB RECORDS CD SEVENDUST ALPHA 7 BROS RECORDS CD SEVENDUST CHAPTER VII: HOPE & SORROW 7 BROS RECORDS CD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM COLD A DIFFERENT DRUM MCD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM ON THE ROAD TO WISDOM A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE ALTERNATES AND REMIXES A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE EVENING BELL, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE FALLING STAR, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE MACHINE BOX A DIFFERENT DRUM BOX BLUE OCTOBER ONE DAY SILVER, ONE DAY GOLD A DIFFERENT DRUM CD BLUE OCTOBER UK INCOMING 10th A DIFFERENT DRUM 2CD CAPSIZE A PERFECT WRECK A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMIC ALLY TWIN SUN A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMICITY ESCAPE POD FOR TWO A DIFFERENT DRUM CD DIGNITY -

T. A. Z. the Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism

T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey Autonomedia Anti-copyright, 1985, 1991. May be freely pirated & quoted-- the author & publisher, however, would like to be informed at: Autonomedia P. O. Box 568 Williamsburgh Station Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Book design & typesetting: Dave Mandl HTML version: Mike Morrison Printed in the United States of America ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CHAOS: THE BROADSHEETS OF ONTOLOGICAL ANARCHISM was first published in 1985 by Grim Reaper Press of Weehawken, New Jersey; a later re-issue was published in Providence, Rhode Island, and this edition was pirated in Boulder, Colorado. Another edition was released by Verlag Golem of Providence in 1990, and pirated in Santa Cruz, California, by We Press. "The Temporary Autonomous Zone" was performed at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, and on WBAI-FM in New York City, in 1990. Thanx to the following publications, current and defunct, in which some of these pieces appeared (no doubt I've lost or forgotten many-- sorry!): KAOS (London); Ganymede (London); Pan (Amsterdam); Popular Reality; Exquisite Corpse (also Stiffest of the Corpse, City Lights); Anarchy (Columbia, MO); Factsheet Five; Dharma Combat; OVO; City Lights Review; Rants and Incendiary Tracts (Amok);Apocalypse Culture (Amok); Mondo 2000; The Sporadical; Black Eye; Moorish Science Monitor; FEH!; Fag Rag; The Storm!; Panic(Chicago); Bolo Log (Zurich); Anathema; Seditious Delicious; Minor Problems (London); AQUA; Prakilpana. Also, thanx to the following individuals: Jim Fleming; James Koehnline; Sue Ann Harkey; Sharon Gannon; Dave Mandl; Bob Black; Robert Anton Wilson; William Burroughs; "P.M."; Joel Birroco; Adam Parfrey; Brett Rutherford; Jake Rabinowitz; Allen Ginsberg; Anne Waldman; Frank Torey; Andr Codrescu; Dave Crowbar; Ivan Stang; Nathaniel Tarn; Chris Funkhauser; Steve Englander; Alex Trotter. -

Bracketing Beelzebub: Satanism Studies And/As Boundary Work”, Paper Presented at the 1St Intl

CONTESO July 2012 Petersen, J. Aa., “Bracketing Beelzebub: Satanism studies and/as boundary work”, paper presented at the 1st intl. conference on Contemporary Esotericism, Stockholm University, August 27-29, 2012. Do not quote or distribute without the explicit permission of the author! Bracketing Beelzebub: Satanism studies and/as boundary-work Jesper Aa. Petersen, NTNU, Norway In any emergent academic study, what determines the nature and extent of the object assumes primary importance. Arguing which phenomena can be said to be paradigmatic and so safely inside, and which are critical for determining the boundaries of the subject, is a recurrent scholarly activity – both to get on the same page internally and to legitimize the field externally. Paradoxically, the criteria for this activity are nevertheless frequently naturalized and implicit, hidden behind common sense assumptions, empirical darlings and pet theories. Thomas Gieryn has proposed the concept of “boundary-work” to capture this duplicity, defining it as the attribution of selected characteristics to [an institution or a subject] (i.e., to its practitioners, methods, stock of knowledge, values and work organization) for purposes of constructing a social boundary that distinguishes some intellectual activities as [outside that boundary]. (Gieryn 1983) The concept has been popular in social studies of science (and non-science) to elaborate on the demarcation principles set forth by e.g. Karl Popper and Robert Merton, but also in anthropological and ethnographic studies of in-group/out-group dynamics outside science. As such, boundary-work has a wide applicability in analyzing knowledge and 1 CONTESO July 2012 practice, or in a more Foucaultian mode, the technologies of power-knowledge in any social field.