Bracketing Beelzebub: Satanism Studies And/As Boundary Work”, Paper Presented at the 1St Intl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

League with Satan. They Said, " He Casts out Devils by Beelzebub." 1

"AS OLD AS METBUSELAH." 449 league with Satan. They said, " He casts out devils by Beelzebub." 1 He is but an embodied falsehood, speaking lies, working a lie, professing to cast out Satan, that He may the better serve him. But the charge was as unwise as unveracious. The answer was easy : " If Satan cast out Satan, how shall his kingdom stand ? If he work against himself, how can his works serve him ? Then, if I cast out devils by Beelzebub, by whom do your disciples cast them out ? By Beelzebub, too ? Let them be your judges."1 The cycle was completed ; fanatical resistance to the light had become fanatical denial of its existence. It was little wonder that Jesus met the deputation from Jerusalem with the question, "Why do ye transgress the commandment of God by your tradition ? • . Ye hypocrites ! well did Esaias prophesy of you, say ing, This people draweth nigh unto me with their mouth, and honoureth me with their lips ; but their heart is far from me."3 "0 ye hypocrites ! ye can discern the face of the sky, but can ye not discern the signs of the times ?"4 A. M. FAIRBAIRN. "AS OLD AS METHUSELAH:" A CHAPTER IN ANTEDILUVIAN CHRONOLOGY. GENESIS V. AccoRDING to the generally accepted rendering of the fifth Chapter of the Book of Genesis, the lives of our antediluvian progenitors are to be reckoned by cen turies, the oldest of them completing a period of nearly a thousand years. Many suggestions have been ten- • Matt. xii 24- • Ibid. xii. 25-27. -

Boyd Rice Is a Putz in My Book, but Examining His Politics, You'll Find a More Compelling and Compelled Point of View Than Many Other Cultural Commentators

Regarding Evil by Ross B. Cisneros B.F.A The Cooper Union School of Art, 2002 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN VISUAL STUDIES AT THE_____ __ ATMTSSACHUSETTS INSTRTUT MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOG OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2005 JUN 28 2005 c 2005 Ross B. Cisneros, All rights reserved. LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic ROTCH copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Degrtmei't Aehitecture '-M~y 6, 2005 Certified by: Krzy'sztof Wodiczko Professor of Visual Arts Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Ad6le Naud6 Santos Chair, Committee on Graduate Students Acting Head, Department of Architecture Dean, School of Architecture and Planning 2 REGARDING EVIL By ROSS B. CISNEROS Submitted to the Department of Architecture On May 6, 2005 in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Visual Studies ABSTRACT The transnational summit, Regarding Evil, was called to assembly with the simultaneous sounding of the trumps in six sites around the world, projected simulcast. In collaboration with the six individuals who were issued the instruments, each announced their particular state of emergency and converged at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with a seventh blast. Scotsman Kenneth Smith assumed the role of 7th piper. Artists and scholars of international reputation had been invited to present visual and discursive material confronting the elusive and immeasurable subject of Evil, its transpolitical behaviors, charismatic aesthetic, and viral disbursement in the vast enterprise of simulation, symbolic power, and catastrophe. -

Medieval Representations of Satan Morgan A

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2011 The aS tanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan Morgan A. Matos [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Matos, Morgan A., "The aS tanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan" (2011). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 28. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/28 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Satanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies By Morgan A. Matos July, 2011 Mentor: Dr. Steve Phelan Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Winter Park Master of Liberal Studies Program The Satanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan Project Approved: _________________________________________ Mentor _________________________________________ Seminar Director _________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College i Table of Contents Table of Contents i Table of Illustrations ii Introduction 1 1. Historical Development of Satan 4 2. Liturgical Drama 24 3. The Corpus Christi Cycle Plays 32 4. The Morality Play 53 5. Dante, Marlowe, and Milton: Lasting Satanic Impressions 71 Conclusion 95 Works Consulted 98 ii Table of Illustrations 1. Azazel from Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal, 1825 11 2. Jesus Tempted in the Wilderness, James Tissot, 1886-1894 13 3. -

![HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8672/how-black-is-black-metal-journalismus-nachrichten-von-heute-488672.webp)

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] nachrichten von heute Kevin Coogan - Lords of Chaos (LOC), a recent book-length examination of the “Satanic” black metal music scene, is less concerned with sound than fury. Authors Michael Moynihan and Didrik Sederlind zero in on Norway, where a tiny clique of black metal musicians torched some churches in 1992. The church burners’ own place of worship was a small Oslo record store called Helvete (Hell). Helvete was run by the godfather of Norwegian black metal, 0ystein Aarseth (“Euronymous”, or “Prince of Death”), who first brought black metal to Norway with his group Mayhem and his Deathlike Silence record label. One early member of the movement, “Frost” from the band Satyricon, recalled his first visit to Helvete: I felt like this was the place I had always dreamed about being in. It was a kick in the back. The black painted walls, the bizarre fitted out with inverted crosses, weapons, candelabra etc. And then just the downright evil atmosphere...it was just perfect. Frost was also impressed at how talented Euronymous was in “bringing forth the evil in people – and bringing the right people together” and then dominating them. “With a scene ruled by the firm hand of Euronymous,” Frost reminisced, “one could not avoid a certain herd-mentality. There were strict codes for what was accept- ed.” Euronymous may have honed his dictatorial skills while a member of Red Ungdom (Red Youth), the youth wing of the Marxist/Leninist Communist Workers Party, a Stalinist/Maoist outfit that idolized Pol Pot. All who wanted to be part of black metal’s inner core “had to please the leader in one way or the other.” Yet to Frost, Euronymous’s control over the scene was precisely “what made it so special and obscure, creating a center of dark, evil energies and inspiration.” Lords of Chaos, however, is far less interested in Euronymous than in the man who killed him, Varg Vikemes from the one-man group Burzum. -

The Doctrine of Satan

Scholars Crossing The Lucifer File Theological Studies 5-2018 The Doctrine of Satan Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lucifer_file Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "The Doctrine of Satan" (2018). The Lucifer File. 1. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lucifer_file/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Lucifer File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DOCTRINE OF SATAN I. The Existence of Satan – There is scarcely a culture, tribe, or society to be found in this world that does not have some concept or fear of an invisible evil power. This has been attested by Christian missionaries and secular anthropologists alike. Witch doctors, shrunken heads, voodoo dolls, and totem poles all give dramatic evidence of this universal fear. One may well ask where this fear came from and of whom are they afraid. The study of the doctrine of Satan may not thrill the soul of man, but it will answer these questions. A. His existence is doubted by the world. 1. As shown by the typical “Walt Disney cartoon concept” – Most of the world today pictures the devil as a medieval and mythical two-horned, fork-tailed impish creature, dressed in red flannel underwear, busily pitching coal into the furnace of hell. -

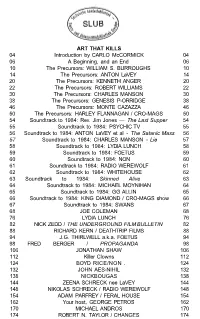

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO Mccormick 04 06 a Beginning, and an End 06 10 the Precursors: WILLIAM S

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO McCORMICK 04 06 A Beginning, and an End 06 10 The Precursors: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS 10 14 The Precursors: ANTON LaVEY 14 20 The Precursors: KENNETH ANGER 20 22 The Precursors: ROBERT WILLIAMS 22 30 The Precursors: CHARLES MANSON 30 38 The Precursors: GENESIS P-ORRIDGE 38 46 The Precursors: MONTE CAZAZZA 46 50 The Precursors: HARLEY FLANNAGAN / CRO-MAGS 50 54 Soundtrack to 1984: Rev. Jim Jones — The Last Supper 54 55 Soundtrack to 1984: PSYCHIC TV 55 56 Soundtrack to 1984: ANTON LaVEY et al - The Satanic Mass 56 57 Soundtrack to 1984: CHARLES MANSON - Lie 57 58 Soundtrack to 1984: LYDIA LUNCH 58 59 Soundtrack to 1984: FOETUS 59 60 Soundtrack to 1984: NON 60 61 Soundtrack to 1984: RADIO WEREWOLF 61 62 Soundtrack to 1984: WHITEHOUSE 62 63 Soundtrack to 1984: Skinned Alive 63 64 Soundtrack to 1984: MICHAEL MOYNIHAN 64 65 Soundtrack to 1984: GG ALLIN 65 66 Soundtrack to 1984: KING DIAMOND / CRO-MAGS show 66 67 Soundtrack to 1984: SWANS 67 68 JOE COLEMAN 68 76 LYDIA LUNCH 76 82 NICK ZEDD / THE UNDERGROUND FILM BULLETIN 82 88 RICHARD KERN / DEATHTRIP FILMS 88 94 J.G. THIRLWELL a.k.a. FOETUS 94 98 FRED BERGER / PROPAGANDA 98 106 JONATHAN SHAW 106 112 Killer Clowns 112 124 BOYD RICE/NON . 124 132 JOHN AES-NIHIL 132 138 NICKBOUGAS 138 144 ZEENA SCHRECK nee LaVEY 144 148 NIKOLAS SCHRECK / RADIO WEREWOLF 148 154 ADAM PARFREY / FERAL HOUSE 154 162 Your host, GEORGE PETROS 162 170 MICHAEL ANDROS 170 174 ROBERT N. -

La Mamelle and the Pic

1 Give Them the Picture: An Anthology 2 Give Them The PicTure An Anthology of La Mamelle and ART COM, 1975–1984 Liz Glass, Susannah Magers & Julian Myers, eds. Dedicated to Steven Leiber for instilling in us a passion for the archive. Contents 8 Give Them the Picture: 78 The Avant-Garde and the Open Work Images An Introduction of Art: Traditionalism and Performance Mark Levy 139 From the Pages of 11 The Mediated Performance La Mamelle and ART COM Susannah Magers 82 IMPROVIDEO: Interactive Broadcast Conceived as the New Direction of Subscription Television Interviews Anthology: 1975–1984 Gregory McKenna 188 From the White Space to the Airwaves: 17 La Mamelle: From the Pages: 87 Performing Post-Performancist An Interview with Nancy Frank Lifting Some Words: Some History Performance Part I Michele Fiedler David Highsmith Carl Loeffler 192 Organizational Memory: An Interview 19 Video Art and the Ultimate Cliché 92 Performing Post-Performancist with Darlene Tong Darryl Sapien Performance Part II The Curatorial Practice Class Carl Loeffler 21 Eleanor Antin: An interview by mail Mary Stofflet 96 Performing Post-Performancist 196 Contributor Biographies Performance Part III 25 Tom Marioni, Director of the Carl Loeffler 199 Index of Images Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA), San Francisco, in Conversation 100 Performing Post-Performancist Carl Loeffler Performance or The Televisionist Performing Televisionism 33 Chronology Carl Loeffler Linda Montano 104 Talking Back to Television 35 An Identity Transfer with Joseph Beuys Anne Milne Clive Robertson -

The Names of Spirits

THE NAMES OF SPIRITS Doug Mason [email protected] SCRIPTURALLY, A PERSON’S “NAME” IS THEIR VERY BEING For the writers of the Judaeo/Christian Scriptures, the term “name” has deep meaning. Even in today’s usage, although we commonly use names as handles that provide identification, the word “name” can have a wider meaning. It could mean “reputation”—good, bad, or otherwise. A person may have a “good name” in the community. The ancients considered a person’s “name” even more profoundly. A person’s “name” was their very self, their total being (1 Sam. 25:25). The margins of Bibles often reveal the reason for a person’s given name or new name. So intimate was the person’s being to their name that when a radical change in a person’s character took place, so that they became a new person, they were given a new name. Examples include: Abraham (Gen. 17:5); Sarah (Gen. 17:15); Israel (Gen. 32:28); Joshua (Num. 13:16); Jedidiah (2 Sam. 12:25); Mara (Ruth 1:20); and Peter (Mark 3:16). “THE SATAN” IN THE HEBREW BIBLE “Satan” appears in only three contexts in the Hebrew Bible: in Job and in Zechariah, where the satan is the prosecuting accuser in the Divine Court in heaven; and in Chronicles, where the blame for David’s census is laid on Satan. “Satan” with the definite article (“the”)—ha satan When the name “satan” appears in the Hebrew Bible with the definite article—”the” satan, ha- satan—it means the role, function, and title1. -

The Devil in Legend and Literature

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenSIUC THE DEVIL IN LEGEND AND LITERATURE ALLEN H. GODBEY, PH.D. DR. RUDWIN has written half a dozen earHer "devil studies" in the past twenty years, dealing chiefly with the use made of the devil in French and German literature. The present volume is primarily a study of "fiendish" elements in the literatures of England, France, and Germany : more narrowly, of their modern literatures. For the devil that Dr. Rudwin would have us consider is a product of the fusion of and conflict of medieval Christianity with pagan divinities and Jewish spooks and dethroned godlings of high and low degree. For devils, historically speaking, are often gods who have lost their jobs: deities sometimes proscribed because they are too popular! The element of political or tribal or eccle- siastical jealousy may be a prominent factor. "Your god is my devil," said Wesley to a theological opponent. The Pahlevi and the Sanscrit are two branches of one language and culture. But the Hindu, like the Roman, declared that divs or devas were the powers to be worshiped, and that the Asuras of the Northern peo- ples were "devils" indeed ! Tit for tat ! Zoroaster retaliates by declaring that an Asura (Ahura-Mazda-Ormuzd) is the Supreme Good, and that all devas are evil, and their worshipers all children of the devas. "There! take that!" Just so, the supreme guardian angel in Assyro-Babylonian lore was a Shedu : the ancestral guardian represented by the human- headed bull-colossi that guarded the gateways of temple and pal- ace. -

Jesus Vs. Beelzebul: the Meaning of His Miracle for Cynics and Skeptics – Part 1 Luke 11:14-23

Jesus Vs. Beelzebul: The Meaning of His Miracle for Cynics and Skeptics – Part 1 Luke 11:14-23 Intro: I. The Miracle (14) The setting for this little confab that Jesus has regarding good, evil, and us arises from a miracle He performed as he journeyed from Capernaum toward Jerusalem. Let’s see it’s very brief description in Lk 11:14 LK 11:14 – Now he was casting out a demon that was mute. When the demon had gone out, the mute man spoke, and the people marveled. The miracle There was a demon possessed man who, as a result of the demon possession, was rendered unable to speak. The demon had a power over him such that his ability either physically or mentally to speak was blunted. For no apparent reason other than evil and hatred of God’s creation, this demon seized the man and rendered him speechless. Luke does not spend much time at all describing the exorcism, he simply says “when the demon had gone out”. When know, however, from the ensuing narrative and reaction of the witnesses that it was Jesus who cast this demon out. When he had done so, the previously voiceless man spoke. Unique among exorcisms In a general sense, this was not a unique occurrence. This is to say that exorcisms were performed by other people of that day as well. Most of those exorcisms were performed over long periods of time with the reading of very extensive and precise incantations that would sometimes work to cast out a demon, and as we will see in the next passage, often fail to keep the demon away for good. -

SMALL TALK Inter Disciplinary Lecture Series

SMALL TALK inter disciplinary lecture series Brief History of Neoliberalism / excerpts from Storm Work/ Industrial Music is Fascism / Tax Shelter films / When We Are Together In The Internet / Tactile Tech / Video Games as Cooperative Performance # 3 SMALL TALK TABLE OF CONTENTS Pitching the film “E.T”. 2 Jack Bride Introduction . 3 Tax Shelter Cinema in Canada . 4 Jonathan Culp Creation Myths (one) . 8 Laura Hudspith & Nicholas Zirk Tactile Tech . 9 Kyle Duffield Garden, page four . 15 Louise Reimer When we are together in the Internet . 16 Jane Frances Dunlop Trophy . .22 Halloway Jones A Breif (Pre-)History of Neoliberalism . .23 Noah Gataveckas Pnp . 27 Morris Fox Industrial Music is Fascism . 28 David Jones I’m okay, you’re “okay.” . 37 Jack Bride Video Games as Cooperative Performance . 38 Michael Palumbo Creation Myths (two) . .40 Laura Hudspith & Nicholas Zirk excerpts fron Storm Work (In Four Voices) . 41 Fan Wu 2 INTRODUCTION Small Talk is an interdisciplinary lecture series and education project in its fourth year of operations – what you hold in your hands is a catalog of writing that came out of our third and fourth seasons. It is an idealistic project, with the goal of sharing knowledge as freely as possible, with complete disregard for the boundaries imposed by traditional academia. Every spring for the past four years, we’ve posted an open call for submissions, and invited those whose work excited us to present it in a live, informal setting. We make almost no restric- tions on the subject matter or presentation style of the partic- ipants, and as such we’ve seen a tremendous pool of activists, fine artists, policy-makers, journalists, technologists, and sci- entists. -

Moldiwhether's Minutes

Volume 2009 Issue 31 Article 11 7-15-2009 Moldiwhether's Minutes Gwenyth E. Hood Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mcircle Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hood, Gwenyth E. (2009) "Moldiwhether's Minutes," The Mythic Circle: Vol. 2009 : Iss. 31 , Article 11. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mcircle/vol2009/iss31/11 This Fiction is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Mythic Circle by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm This fiction is available in The Mythic Circle: https://dc.swosu.edu/mcircle/vol2009/iss31/11 EDITORIAL AND COMMENTARY (continued from p. 3 ) literary critic Squidgeboodle. We haven’t heard from Squidgeboodle for a while, but apparently he is up to his old tricks. As before, I’m not certain how the drafted minutes of his committee meeting reached my laptop, but in the spirit of giving the devil his due, I print them here, trusting my wise readers to make all necessary allowances for the diabolic viewpoint expressed there.