SMALL TALK Inter Disciplinary Lecture Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printed Covers Sailing Through the Air As Their Tables Are REVIEWS and REFUTATIONS Ipped

42 RECOMMENDED READING Articles Apoliteic music: Neo-Folk, Martial Industrial and metapolitical fascism by An- ton Shekhovtsov Former ELF/Green Scare Prisoner Exile Now a Fascist by NYC Antifa Books n ٻThe Nature of Fascism by Roger Gri Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler by Roger n ٻGri n ٻFascism edited by Roger Gri Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity by Nicholas Go- A FIELD GUIDE TO STRAW MEN odrick-Clarke Gods of the Blood: The Pagan Revival and White Separatism by Mattias Gardell Modernity and the Holocaust by Zygmunt Bauman Sadie and Exile, Esoteric Fascism, and Exterminate All the Brutes by Sven Lindqvist Confronting Fascism: Discussion Documents for a Militant Movement by Don Hamerquist, Olympias Little White Lies J. Sakai, Anti-Racist Action Chicago, and Mark Salotte Baedan: A Journal of Queer Nihilism Baedan 2: A Queer Journal of Heresy Baedan 3: A Journal of Queer Time Travel Against His-story, Against Leviathan! by Fredy Perlman Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation by Silvia Federici Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture by Arthur Evans The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revo- lutionary Atlantic by Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker Gone to Croatan: Origins of North American Dropout Culture edited by Ron Sakolsky and James Koehnline The Subversion of Politics: European Autonomous Social Movements and the Decolonization of Everyday Life by Georgy Katsia cas 1312 committee // February 2016 How the Irish Became White by Noel Ignatiev How Deep is Deep Ecology? by George Bradford Against the Megamachine: Essays on Empire and Its Enemies by David Watson Elements of Refusal by John Zerzan Against Civilization edited by John Zerzan This World We Must Leave and Other Essays by Jacques Camatte 41 total resistance mounted to the advent of industrial society. -

Boyd Rice Is a Putz in My Book, but Examining His Politics, You'll Find a More Compelling and Compelled Point of View Than Many Other Cultural Commentators

Regarding Evil by Ross B. Cisneros B.F.A The Cooper Union School of Art, 2002 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN VISUAL STUDIES AT THE_____ __ ATMTSSACHUSETTS INSTRTUT MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOG OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2005 JUN 28 2005 c 2005 Ross B. Cisneros, All rights reserved. LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic ROTCH copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Degrtmei't Aehitecture '-M~y 6, 2005 Certified by: Krzy'sztof Wodiczko Professor of Visual Arts Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Ad6le Naud6 Santos Chair, Committee on Graduate Students Acting Head, Department of Architecture Dean, School of Architecture and Planning 2 REGARDING EVIL By ROSS B. CISNEROS Submitted to the Department of Architecture On May 6, 2005 in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Visual Studies ABSTRACT The transnational summit, Regarding Evil, was called to assembly with the simultaneous sounding of the trumps in six sites around the world, projected simulcast. In collaboration with the six individuals who were issued the instruments, each announced their particular state of emergency and converged at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with a seventh blast. Scotsman Kenneth Smith assumed the role of 7th piper. Artists and scholars of international reputation had been invited to present visual and discursive material confronting the elusive and immeasurable subject of Evil, its transpolitical behaviors, charismatic aesthetic, and viral disbursement in the vast enterprise of simulation, symbolic power, and catastrophe. -

Descent V 1999

w< >l F=Fli >w , ^ >< c Q. (5 (/) >< Q Q 3 ifl 1 u -i — — n 3 "0 3 ^ ?r S (11 • ii ir-ji I- ^ .*> a - i J The ajna Offensive is pro 1 ^ I <4 ( present a series of aui interpretations of visual / Recently the realization set in with me about my current surroundings and lack of inspirational environs, and the difference between those and newly rediscovered potentials. the self-limitations one imposes. since leaving europe it has been this way it seems, in general, the fountain of vision/creativity has been tapped a bit by a _ and shallow production outlook... it became clearer recently what was ULTRA fistic and characteristic expression and what wasn't. unfortunately, over the "ABANDONED"/ THIS LACK OF CREATIVE INFLUXLUX HAS SPILLED OVER TO MY WORK WITH THIS MAGAZINE, IT .AND FORGOTTEN' T SEVERAL NOT SO IMPORTANT (UPONON REFLECTION) IDEAS AND ATTITUDESATTITU CLOUDED OVER 7" OF MY WORK HERE, LUCKILY TYLER HAS KEPT•'-'•- THE- '- FIRE BURNING - HEART OF HANK YOU SO VERY MUCH MR. DAVIS. SO, THE DEATH ISSUE DO LLY HAVE IMPRESSIONS FROM HANS BELMER, MUCH TO DO WITH THE MAGAZINE ITSELF BUT IT'S RATHER A DOCUMENT OF PERSONAL LIMITED TO 300 COPIES ISSUES. AS I EMBARK AWAY FROM THE WEST COAST AGAIN FOR AN'T REALLY + 26 LETTERED AND SIGNED EDITIONS ENVISION WHAT IS NEXT FOR THIS PUBLICATION... OR OTHERWISE.... HER THAN ANNOUNCE OR $8 US/$10 OVERSEAS PREDICT THE NEXT MOVE AS WE HAVE IN THE PAST ;W NATURALLY THIS TIME, THE WAY IT SHOULD BE. IT'S ALWAYS A SLOW, PA IEND DESCRIBED IT) BUT MAYBE IT ALWAYS WAS SO BECAUSE VIOUS EXPECTATIONS. -

Throbbing Gristle Reissue Series PR

THROBBING GRISTLE THE REFORMATION YEARS NEW REISSUES SERIES OUT 13 DECEMBER 2019: Part Two: The Endless Not TG Now A Souvenir of Camber Sands “The Endless Not features some of the subtlest songwriting of TG's career, playing that knot of tension for all its worth and all the more disturbing for how pensive and restrained it feels” - Pitchfork “…more of a rebirthing than a reunion” - Tiny Mix Tapes “a gristly comeback”” - DJ Throbbing Gristle announce the next phase of their reissues series with the release of Part Two: The Endless Not, TG Now and A Souvenir of Camber Sands, out on CD and limited edition vinyl on 13 December 2019. In 2004 Chris Carter, Peter Christopherson, Genesis P. Orridge and Cosey Fanni Tutti reformed - 23 years after their mission was originally terminated - and between 2004 and 2007 the band released 14 new studio tracks and a live album of their appearance at ATP's Nightmare Before Christmas in Camber Sands. TG Now, originally released in 2004, was the sound of Throbbing Gristle testing the waters, seeing how it felt to work together again. The 4-track limited vinyl and CD release was available originally to attendees of the RE-TG Astoria event in 2004, their first performance together since 1981’s US tour. With Part Two: The Endless Not, the band returned to the studio after deciding they had unfinished creative business outside of the live arena. Released in 2007, over 25 years after their last studio album, the album was, as Tiny Mix Tapes put it, “…more of a rebirthing than a reunion”. -

Throbbing Gristle 40Th Anniv Rough Trade East

! THROBBING GRISTLE ROUGH TRADE EAST EVENT – 1 NOV CHRIS CARTER MODULAR PERFORMANCE, PLUS Q&A AND SIGNING 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEBUT ALBUM THE SECOND ANNUAL REPORT Throbbing Gristle have announced a Rough Trade East event on Wednesday 1 November which will see Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti in conversation, and Chris Carter performing an improvised modular set. The set will be performed predominately on prototypes of a brand new collaboration with Tiptop Audio. Chris Carter has been working with Tiptop Audio on the forthcoming Tiptop Audio TG-ONE Eurorack module, which includes two exclusive cards of Throbbing Gristle samples. Chris Carter has curated the sounds from his personal sonic archive that spans some 40 years. Card one consists of 128 percussive sounds and audio snippets with a second card of 128 longer samples, pads and loops. The sounds have been reworked and revised, modified and mangled by Carter to give the user a unique Throbbing Gristle sounding palette to work wonders with. In addition to the TG themed front panel graphics, the module features customised code developed in collaboration with Chris Carter. In addition, there will be a Throbbing Gristle 40th Anniversary Q&A event at the Rough Trade Shop in New York with Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, date to be announced. The Rough Trade Event coincides with the first in a series of reissues on Mute, set to start on the 40th anniversary of their debut album release, The Second Annual Report. On 3 November 2017 The Second Annual Report, presented as a limited edition white vinyl release in the original packaging and also on double CD, and 20 Jazz Funk Greats, on green vinyl and double CD, will be released, along with, The Taste Of TG: A Beginner’s Guide to Throbbing Gristle with an updated track listing that will include ‘Almost A Kiss’ (from 2007’s Part Two: Endless Not). -

![HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8672/how-black-is-black-metal-journalismus-nachrichten-von-heute-488672.webp)

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] nachrichten von heute Kevin Coogan - Lords of Chaos (LOC), a recent book-length examination of the “Satanic” black metal music scene, is less concerned with sound than fury. Authors Michael Moynihan and Didrik Sederlind zero in on Norway, where a tiny clique of black metal musicians torched some churches in 1992. The church burners’ own place of worship was a small Oslo record store called Helvete (Hell). Helvete was run by the godfather of Norwegian black metal, 0ystein Aarseth (“Euronymous”, or “Prince of Death”), who first brought black metal to Norway with his group Mayhem and his Deathlike Silence record label. One early member of the movement, “Frost” from the band Satyricon, recalled his first visit to Helvete: I felt like this was the place I had always dreamed about being in. It was a kick in the back. The black painted walls, the bizarre fitted out with inverted crosses, weapons, candelabra etc. And then just the downright evil atmosphere...it was just perfect. Frost was also impressed at how talented Euronymous was in “bringing forth the evil in people – and bringing the right people together” and then dominating them. “With a scene ruled by the firm hand of Euronymous,” Frost reminisced, “one could not avoid a certain herd-mentality. There were strict codes for what was accept- ed.” Euronymous may have honed his dictatorial skills while a member of Red Ungdom (Red Youth), the youth wing of the Marxist/Leninist Communist Workers Party, a Stalinist/Maoist outfit that idolized Pol Pot. All who wanted to be part of black metal’s inner core “had to please the leader in one way or the other.” Yet to Frost, Euronymous’s control over the scene was precisely “what made it so special and obscure, creating a center of dark, evil energies and inspiration.” Lords of Chaos, however, is far less interested in Euronymous than in the man who killed him, Varg Vikemes from the one-man group Burzum. -

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES: STAHLPLANET – Leviamaag Boxset || CD-R + DVD BOX // 14,90 € DMB001 | Origin: Germany | Time: 71:32 | Release: 2008 Dark and weird One-man-project from Thüringen. Ambient sounds from the world Leviamaag. Black box including: CD-R (74min) in metal-package, DVD incl. two clips, a hand-made booklet on transparent paper, poster, sticker and a button. Limited to 98 units! STURMKIND – W.i.i.L. || CD-R // 9,90 € DMB002 | Origin: Germany | Time: 44:40 | Release: 2009 W.i.i.L. is the shortcut for "Wilkommen im inneren Lichterland". CD-R in fantastic handmade gatefold cover. This version is limited to 98 copies. Re-release of the fifth album appeared in 2003. Originally published in a portfolio in an edition of 42 copies. In contrast to the previous work with BNV this album is calmer and more guitar-heavy. In comparing like with "Die Erinnerung wird lebendig begraben". Almost hypnotic Dark Folk / Neofolk. KNŒD – Mère Ravine Entelecheion || CD // 8,90 € DMB003 | Origin: Germany | Time: 74:00 | Release: 2009 A release of utmost polarity: Sudden extreme changes of sound and volume (and thus, in mood) meet pensive sonic mindscapes. The sounds of strings, reeds and membranes meet the harshness and/or ambience of electronic sounds. Music as harsh as pensive, as narrative as disrupt. If music is a vehicle for creating one's own world, here's a very versatile one! Ambient, Noise, Experimental, Chill Out. CATHAIN – Demo 2003 || CD-R // 3,90 € DMB004 | Origin: Germany | Time: 21:33 | Release: 2008 Since 2001 CATHAIN are visiting medieval markets, live roleplaying events, roleplaying conventions, historic events and private celebrations, spreading their “Enchanting Fantasy-Folk from worlds far away”. -

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO Mccormick 04 06 a Beginning, and an End 06 10 the Precursors: WILLIAM S

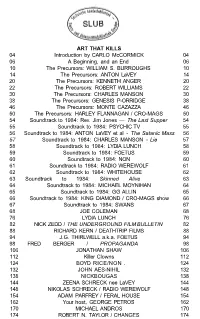

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO McCORMICK 04 06 A Beginning, and an End 06 10 The Precursors: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS 10 14 The Precursors: ANTON LaVEY 14 20 The Precursors: KENNETH ANGER 20 22 The Precursors: ROBERT WILLIAMS 22 30 The Precursors: CHARLES MANSON 30 38 The Precursors: GENESIS P-ORRIDGE 38 46 The Precursors: MONTE CAZAZZA 46 50 The Precursors: HARLEY FLANNAGAN / CRO-MAGS 50 54 Soundtrack to 1984: Rev. Jim Jones — The Last Supper 54 55 Soundtrack to 1984: PSYCHIC TV 55 56 Soundtrack to 1984: ANTON LaVEY et al - The Satanic Mass 56 57 Soundtrack to 1984: CHARLES MANSON - Lie 57 58 Soundtrack to 1984: LYDIA LUNCH 58 59 Soundtrack to 1984: FOETUS 59 60 Soundtrack to 1984: NON 60 61 Soundtrack to 1984: RADIO WEREWOLF 61 62 Soundtrack to 1984: WHITEHOUSE 62 63 Soundtrack to 1984: Skinned Alive 63 64 Soundtrack to 1984: MICHAEL MOYNIHAN 64 65 Soundtrack to 1984: GG ALLIN 65 66 Soundtrack to 1984: KING DIAMOND / CRO-MAGS show 66 67 Soundtrack to 1984: SWANS 67 68 JOE COLEMAN 68 76 LYDIA LUNCH 76 82 NICK ZEDD / THE UNDERGROUND FILM BULLETIN 82 88 RICHARD KERN / DEATHTRIP FILMS 88 94 J.G. THIRLWELL a.k.a. FOETUS 94 98 FRED BERGER / PROPAGANDA 98 106 JONATHAN SHAW 106 112 Killer Clowns 112 124 BOYD RICE/NON . 124 132 JOHN AES-NIHIL 132 138 NICKBOUGAS 138 144 ZEENA SCHRECK nee LaVEY 144 148 NIKOLAS SCHRECK / RADIO WEREWOLF 148 154 ADAM PARFREY / FERAL HOUSE 154 162 Your host, GEORGE PETROS 162 170 MICHAEL ANDROS 170 174 ROBERT N. -

Download the PDF Here

From the Mail Art network, We—’We’ being Jaye and me as one physical being, just to VESTED clarify*—We, as Genesis in those days, heard from an artist called Anna Banana. One day she wrote to me and we asked her about this mythical INTEREST fi gure we’d heard about called Monte Cazazza. She wrote back and said, ‘Monte Cazazza is a Genesis Breyer P-Orridge in conversation sick, dangerous, sociopathic individual. Why, with Mark Beasley once, Monte came to an art opening dressed like a woman in his long coat, carrying a briefcase and waving a Magnum revolver. In the briefcase was a dead cat and he locked the doors, held everybody in the art opening at gunpoint, took the cat out, poured lighter fl uid on it and set it on fi re. Oh, and the stench fi lled the room. He just started to laugh and then he left again. You don’t want to know this person!’ Wrong. (laughs) We did wantwant to know this person. Of course, once we heard how awful he was, we decided to correspond with Monte. We used to send each other the most grotesque and unpleasant things we could think of. One time, we sent him a big padded envelope and inside it were a pint of maggots and chicken legs and offal from the butcher, mixed up with pornography and so on. By the time it got to California to his P.O. Box, it stank! He was temporarily restrained by the security at the post offi ce. -

December 2020 New Releases

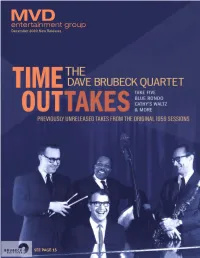

December 2020 New Releases SEE PAGE 15 what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 59 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 12 FEATURED RELEASES Video WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. THE DAVE BRUBECK THE RESIDENTS - 35 FEATURING MICK ROSSI - QUARTET - IN BETWEEN DREAMS: Film LIVE IN TOKYO TIME OUTTAKES LIVE IN SAN FRANCISCO Films & Docs 36 Faith & Family 56 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 57 Order Form 69 Deletions & Price Changes 65 TREMORS MANIAC A NIGHT IN CASABLANCA 800.888.0486 (2-DISC SPECIAL EDITION) 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 www.MVDb2b.com WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. BERT JANSCH - SUPERSUCKERS - FEATURING MICK ROSSI - BEST OF LIVE MOTHER FUCKERS BE TRIPPIN’ TIME OUT AND TAKE FIVE! LIVE IN TOKYO We could use a breather from what has been a most turbulent year, and with our December releases, we provide a respite with fantastic discoveries in the annals of cool jazz. THE DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET “TIME OUTTAKES” is an alternate version of the masterful TIME OUT 1959 LP, with the seven tracks heard for the first time in crisp, different versions with a bonus track and studio banter. The album’s “Take Five” is the biggest selling jazz single ever, and hearing this in different form is downright thrilling. On LP and CD. Also smooth jazz reigns supreme with a CD release of a newly discovered live performance from sax legend GEORGE COLEMAN. “IN BALTIMORE” is culled from a 1971 performance with detailed liner notes and rare photos. Kick Out the Jazz! Something else we could use is a release from oddball novelty song collector DR. -

DEAD CHANNEL SURFING: Cyberpunk and Industrial Music

DEAD CHANNEL SURFING: Cyberpunk and industrial music In the early 1980s from out of Vancouver, home of cyberpunk writer William Gibson and science fiction film-maker David Cronenberg, came a series of pioneering bands with a similar style and outlook. The popular synth-pop band Images in Vogue, after touring with Duran Duran and Roxy Music, split into several influential factions. Don Gordon went on to found Numb, Kevin Crompton to found Skinny Puppy, and Ric Arboit to form Nettwerk Records, which would later release Skinny Puppy, Severed Heads, Moev, Delerium and more. Controversial band Numb ended up receiving less attention than the seminal Skinny Puppy. Kevin Crompton (now called Cevin Key) joined forces with Kevin Ogilvie (Nivek Ogre) and began their career by playing in art galleries. After their friend Bill Leeb quit citing ‘creative freedom’ disputes, they embarked on a new style along with the help of newly recruited Dwayne Goettel. Leeb would go on to found Front Line Assembly with Rhys Fulber in 1986. The style of music created by these bands, as well as many similar others, has since been dubbed ‘cyberpunk’ by some journalists. Cyberpunk represents an interesting coupling of concepts. It can be dissected, as Istvan Csiscery-Ronay has shown, into its two distinct parts, ‘cyber’ and ‘punk’. Cyber refers to cybernet- ics, the study of information and control in man and machine, which was created by U.S. American mathematician Norbert Wiener fifty years ago. Wiener fabricated the word from the Greek kyber- netes, meaning ‘governor’, ‘steersman’ or ‘pilot’ (Leary, 1994: 66). The second concept, punk, in the sense commonly used since 1976, is a style of music incorporating do-it-yourself (d.i.y) techniques, centred on independence and touting anarchist attitudes. -

La Mamelle and the Pic

1 Give Them the Picture: An Anthology 2 Give Them The PicTure An Anthology of La Mamelle and ART COM, 1975–1984 Liz Glass, Susannah Magers & Julian Myers, eds. Dedicated to Steven Leiber for instilling in us a passion for the archive. Contents 8 Give Them the Picture: 78 The Avant-Garde and the Open Work Images An Introduction of Art: Traditionalism and Performance Mark Levy 139 From the Pages of 11 The Mediated Performance La Mamelle and ART COM Susannah Magers 82 IMPROVIDEO: Interactive Broadcast Conceived as the New Direction of Subscription Television Interviews Anthology: 1975–1984 Gregory McKenna 188 From the White Space to the Airwaves: 17 La Mamelle: From the Pages: 87 Performing Post-Performancist An Interview with Nancy Frank Lifting Some Words: Some History Performance Part I Michele Fiedler David Highsmith Carl Loeffler 192 Organizational Memory: An Interview 19 Video Art and the Ultimate Cliché 92 Performing Post-Performancist with Darlene Tong Darryl Sapien Performance Part II The Curatorial Practice Class Carl Loeffler 21 Eleanor Antin: An interview by mail Mary Stofflet 96 Performing Post-Performancist 196 Contributor Biographies Performance Part III 25 Tom Marioni, Director of the Carl Loeffler 199 Index of Images Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA), San Francisco, in Conversation 100 Performing Post-Performancist Carl Loeffler Performance or The Televisionist Performing Televisionism 33 Chronology Carl Loeffler Linda Montano 104 Talking Back to Television 35 An Identity Transfer with Joseph Beuys Anne Milne Clive Robertson