This Is Our Music V.2-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bbc Music Jazz 4

Available on your digital radio, online and bbc.co.uk/musicjazz THURSDAY 10th NOVEMBER FRIDAY 11th NOVEMBER SATURDAY 12th NOVEMBER SUNDAY 13th NOVEMBER MONDAY 14th NOVEMBER JAZZ NOW LIVE WITH JAZZ AT THE MOVIES WITH 00.00 - SOMERSET BLUES: 00.00 - JAZZ AT THE MOVIES 00.00 - 00.00 - WITH JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 1) SOWETO KINCH CONTINUED JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 2) THE STORY OF ACKER BILK Clarke Peters tells the strory of Acker Bilk, Jamie Cullum explores jazz in films – from Al Soweto Kinch presents Jazz Now Live from Jamie celebrates the work of some of his one of Britain’s finest jazz clarinettists. Jolson to Jean-Luc Godard. Pizza Express Dean Street in London. favourite directors. NEIL ‘N’ DUD – THE OTHER SIDE JAZZ JUNCTIONS: JAZZ JUNCTIONS: 01.00 - 01.00 - ELLA AT THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL 01.00 - 01.00 - OF DUDLEY MOORE JAZZ ON THE RECORD THE BIRTH OF THE SOLO Neil Cowley's tribute to his hero Dudley Ella Fitzgerald, live at the Royal Albert Hall in Guy Barker explores the turning points and Guy Barker looks at the birth of the jazz solo Moore, with material from Jazz FM's 1990 heralding the start of Jazz FM. pivotal events that have shaped jazz. and the legacy of Louis Armstrong. archive. GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: GUY BARKER’S JAZZ COLLECTION: GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - 02.00 - GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - THE OTHER SIDE OF THE POND: 02.00 - TRUMPET MASTERS (PT. 2) JAZZ FESTIVALS (PT. 1) JAZZ ON FILM (PT. -

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

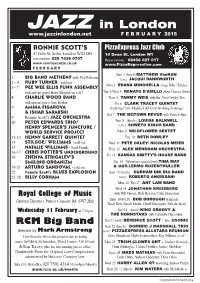

JAZZ in London F E B R U a R Y 2015

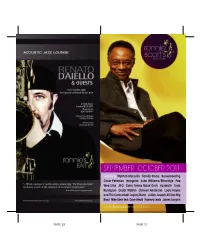

JAZZ in London www.jazzinlondon.net F E B R U A R Y 2015 RONNIE SCOTT’S PizzaExpress Jazz Club 47 Frith St. Soho, London W1D 4HT 10 Dean St. London W1 reservations: 020 7439 0747 Reservations: 08456 027 017 www.ronniescotts.co.uk www.PizzaExpresslive.com F E B R U A R Y Sun 1 (lunch) MATTHEW VanKAN with Phil Robson 1 BIG BAND METHENY (eve) JACQUI DANKWORTH 2 - 4 RUBY TURNER - sold out Mon 2 sings Billie Holiday 5 - 7 PEE WEE ELLIS FUNK ASSEMBLY EDANA MINGHELLA with special guest Huey Morgan on 6 & 7 Tue 3/Wed 4 RENATO D’AIELLO plays Horace Silver 8 CHARLIE WOOD BAND Thur 5 TAMMY WEIS with the Tom Cawley Trio with special guest Guy Barker Fri 6 CLARK TRACEY QUINTET 9 AMINA FIGAROVA featuring Chris Maddock & Henry Armburg-Jennings & ISHAR SARABSKI Sat 7 THE MOTOWN REVUE with Patrick Alan 9 Ronnie Scott’s JAZZ ORCHESTRA 10 PETER EDWARDS TRIO/ Sun 8 (lunch) LOUISE BALKWILL (eve) HENRY SPENCER’S JUNCTURE / SOWETO KINCH BAND WORLD SERVICE PROJECT Mon 9 WILDFLOWER SEXTET 11- 13 KENNY GARRETT QUINTET Tue 10 BETH ROWLEY 14 STILGOE/ WILLIAMS - sold out Wed 11 PETE OXLEY/ NICOLAS MEIER 15 - Soul Family NATALIE WILLIAMS Thur 12 ALEX MENDHAM ORCHESTRA 16-17 CHRIS POTTER’S UNDERGROUND Fri 13 18 ZHENYA STRIGALEV’S KANSAS SMITTY’S HOUSE BAND SMILING ORGANIZM Sat 14 Valentine’s special with TINA MAY 19-21 ARTURO SANDOVAL - sold out & GUILLERMO ROZENTHULLER 22 Ronnie Scott’s BLUES EXPLOSION Sun 15 (lunch) DURHAM UNI BIG BAND 23-28 BILLY COBHAM (eve) ROBERTO ANGRISANI Mon 16/ Tue17 ANT LAW BAND Wed 18 JONATHAN KREISBERG Royal College of Music with Will Vinson, Rick Rosato, Colin Stranahan (Britten Theatre) Prince Consort Rd. -

Trad Dads, Dirty Boppers and Free Fusioneers, British Jazz, 1960-1974

Trad Dads, Dirty Boppers and Free Fusioneers, British Jazz, 1960-1974 Duncan Heining Sheffield and Bristol, CT: Equinox, 2013. ISBN: 978-1-84553-405-9 (HB) Katherine Williams University of Plymouth [email protected] In Trad Dads, Dirty Boppers and Free Fusioneers, British Jazz 1960–1974, Duncan Heining has made a significant contribution to the available literature on British jazz. His effort is particularly valuable for addressing a period that is largely neglected; although the same period is covered from a fusion perspective in Ian Carr’s Music Outside (1973, rev. 2008) and Stuart Nicholson’s Jazz-Rock (1998), to my knowledge Heining has provided the first full-length study of the period from a jazz angle. Trad Dads provides a wealth of information, and is packed densely with facts and anecdotes, many of which he gained through a series of original interviews with prominent musicians and organizers, including Chris Barber, Barbara Thompson, Barry Guy, Gill Alexander and Bill Ashton. Throughout the monograph, he makes a case for the unique identity and sound of British jazz. The timeframe he has picked is appropriate for this observation, for there are several homegrown artists on the scene who have been influenced by the musicians around them, rather than just visiting US musicians (examples include Jon Hiseman and Graham Bond). Heining divides his study thematically rather than chronologically, using race, class, gender and political stance as themes. Chapters 1 to 3 set the scene in Britain during this period, which has the dual purpose of providing useful background information and an extended introduction. -

Air Artist Agency

Air Artist Agency, in GERMANY & AUSTRIA MARCH 2011 Air Artist Agency, THE CONCEPT I was welcomed and In March 2011, six of Britain’s most exciting and forward-thinking bands will invited to England in be descending on Germany and Austria to perform 72 gigs over the period of two weeks. 12 clubs in 12 different cities will be running a ‘Brit-Jazz- the friendliest of ways. Week’ and hosting performances from a different one of the bands London is without each night. doubt Europe´s capital Between them, the bands have been recognised by the MOBO and for culture. There are MOJO Awards, Mercury Music Prize and just about every British Jazz a dozen great concerts Award available! They have all toured internationally but this is the to go to every day, all first time any of them will be presented in Germany and Austria in museums are free and such a big way. the local music scene is With influences as diverse as Indian music, Hip-Hop, Rap, Trip-Hop and vibrant, energetic and Rock, the bands involved are ex-Portishead Jazz-Rockers Get The Blessing, imaginative with a great saxophonist Jason Yarde, Indo-Jazz Clarinettist Arun Ghosh, pianist Kit Downes, mixture of artists from The Julian Siegel Quartet and rapper-saxophonist Soweto Kinch. all sorts of backgrounds; We are organising full German/Austrian press coverage for the event and one of a true melting pot of the main aims of the project is to launch each of the bands in this territory and build the foundations for regular touring in Germany and Austria. -

ART FARMER NEA Jazz Master (1999)

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. ART FARMER NEA Jazz Master (1999) Interviewee: Art Farmer (August 21, 1928 – October 4, 1999) Interviewer: Dr. Anthony Brown Dates: June 29-30, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 96 pp. Brown: Today is June 29, 1995. This is the Jazz Oral History Program interview for the Smithsonian Institution with Art Farmer in one of his homes, at least his New York based apartment, conducted by Anthony Brown. Mr. Farmer, if I can call you Art, would you please state your full name? Farmer: My full name is Arthur Stewart Farmer. Brown: And your date and place of birth? Farmer: The date of birth is August 21, 1928, and I was born in a town called Council Bluffs, Iowa. Brown: What is that near? Farmer: It across the Mississippi River from Omaha. It’s like a suburb of Omaha. Brown: Do you know the circumstances that brought your family there? Farmer: No idea. In fact, when my brother and I were four years old, we moved Arizona. Brown: Could you talk about Addison please? Farmer: Addison, yes well, we were twin brothers. I was born one hour in front of him, and he was larger than me, a bit. And we were very close. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 1 Brown: So, you were fraternal twins? As opposed to identical twins? Farmer: Yes. Right. -

June 2020 Volume 87 / Number 6

JUNE 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

ISSUE 22 ° May 2011

Ne w s L E T T e R Editor: Dave Gelly ISSUE 22 ° May 2011 Ready for the Second Round We have now success- packs on the theme ‘The fully completed the devel- Story of British Jazz’, empha- opment phase of the sising the people and places Simon Spillett Talkin’ (and Access Development involved, and also the wider Playin’) Tubby Project for the Heritage social and cultural aspect of A celebration of the Music, Life Lottery Fund bid. Working the times. Some of these are NATIONAL JAZZ ARCHIVE JAZZ NATIONAL and times of the late, great British with Essex Record Office touched on in the Archive’s and Flow Associates, our exhibition at the Barbican jazz legend Tubby Hayes education and outreach Music Library (see below). With John Critchinson (piano), consultants, we have Alec Dankworth (bass) and developed our plans to Clark Tracey (drums) apply for the second NJA Exhibition Saturday 23 July 2011 round – funding of £388,000 opens at Barbican 1.30 - 4.30pm, at Loughton Methodist Church for a three-year delivery Music Library project. Tickets £10 from David Nathan at The Archive’s exhibition the Archive (cheques payable to This will involve building at the Barbican Music Library National Jazz Archive) on what we have so far is set to open on Tuesday 3rd See also Pages 5 & 6 achieved in increasing access May. It presents the people, to our collections during the places, bands and great jazz development phase - con- events, portrayed in rare serving, cataloguing, digitis- photos, posters, books, ing, developing outreach magazines and ephemera facilities, and collaborating from our fast-growing on projects with those who collection. -

Grover Kemble and Za Zu Zaz Reunion

Volume 39 • Issue 7 July/August 2011 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. above: Winard Harper Sextet; below: Allan Harris. Photos by Tony Mottola. 2011 “Ring dem Bells!” azzfest 2011 on June 11 at the College of Saint J Elizabeth in Morristown kicked off with the ringing of the noon bells at Anunciation Hall just as Emily Asher’s Garden Party was set to begin playing outside its entrance. That caused only a minor setback at our brand new venue where the benefits outweighed any clouds and drizzle. All activities had been seamlessly moved indoors, which turned out to be a boon for one and all, with no missed notes. Dolan Hall proved to be a beautiful venue and the Jazz Lobsters easily fanned across its stage. The languid start to “Splanky” gave way to a crisp, sparking horn crescendo. Bari sax man Larry McKenna was featured as arranger and soloist on “You Go to My Head,” and his velvety, luxurious tone sparked bandleader/ pianist James Lafferty’s continued on page 30 New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: Deconstructing Dave NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY April Jazz Social: Dave Frank . 2 Dave Frank digs into Dave McKenna at April Jazz Social Bulletin Board . 2 Governor’s Island Jazz Party 2011 . 3 Text and photos Mail Bag. 3 by Tony Mottola NJJS Calendar . 3 Co-Editor Jersey Jazz Jazz Trivia . 4 Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info . 6 ianist and educator May Jazz Social: Sue Giles . 52 PDave Frank explored Crow’s Nest . -

Blues in the Blood a M U E S L B M L E O O R D

March 2011 | No. 107 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com J blues in the blood a m u e s l b m l e o o r d Johnny Mandel • Elliott Sharp • CAP Records • Event Calendar In his play Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare wrote, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” It is a lovely sentiment but one with which we agree only partially. So with that introduction, we are pleased to announce that as of this issue, the gazette formerly known as AllAboutJazz-New York will now be called The New York City Jazz Record. It is a change that comes on the heels of our separation New York@Night last summer from the AllAboutJazz.com website. To emphasize that split, we felt 4 it was time to come out, as it were, with our own unique identity. So in that sense, a name is very important. But, echoing Shakespeare’s idea, the change in name Interview: Johnny Mandel will have no impact whatsoever on our continuing mission to explore new worlds 6 by Marcia Hillman and new civilizations...oh wait, wrong mission...to support the New York City and international jazz communities. If anything, the new name will afford us new Artist Feature: Elliott Sharp opportunities to accomplish that goal, whether it be in print or in a soon-to-be- 7 by Martin Longley expanded online presence. We are very excited for our next chapter and appreciate your continued interest and support. On The Cover: James Blood Ulmer But back to the business of jazz. -

October 2011

SEPTEMBE R - OCTOBER 2011 Featuring: Wynton Marsalis | Family Stone | Remembering Oscar Peterson | Incognito | John Williams/Etheridge | Pee Wee Ellis | JTQ | Colin Towns Mask Orch | Azymuth | Todd Rundgren | Cedar Walton | Carleen Anderson | Louis Hayes and The Cannonball Legacy Band | Julian Joseph All Star Big Band | Mike Stern feat. Dave Weckl | Ramsey Lewis | James Langton Cover artist: Ramsey Lewis Quintet (Thur 27 - Sat 29 Oct) PAGE 28 PAGE 01 Membership to Ronnie Scotts GIGS AT A GLANCE SEPTEMBER THU 1 - SAT 3: JAMES HUNTER SUN 4: THE RONNIE SCOTT’S JAZZ ORCHESTRA PRESENTS THE GENTLEMEN OF SWING MON 5 - TUE 6: THE FAMILY STONE WED 7 - THU 8: REMEMBERING OSCAR PETERSON FEAT. JAMES PEARSON & DAVE NEWTON FRI 9 - SAT 10: INCOGNITO SUN 11: NATALIE WILLIAMS SOUL FAMILY MON 12 - TUE 13: JOHN WILLIAMS & JOHN ETHERIDGE WED 14: JACQUI DANKWORTH BAND THU 15 - SAT 17: PEE WEE ELLIS - FROM JAZZ TO FUNK AND BACK SUN 18: THE RONNIE SCOTT’S BLUES EXPLOSION MON 19: OSCAR BROWN JR. TRIBUTE FEATURING CAROL GRIMES | 2 free tickets to a standard price show per year* TUE 20 - SAT 24: JAMES TAYLOR QUARTET SUN 25: A SALUTE TO THE BIG BANDS | 20% off all tickets (including your guests!)** WITH THE RAF SQUADRONAIRES | Dedicated members only priority booking line. MON 26 - TUE 27: ROBERTA GAMBARINI | Jump the queue! Be given entrance to the club before Non CELEBRATING MILES DAVIS 20 YEARS ON Members (on production of your membership card) WED 28 - THU 29: ALL STARS PLAY ‘KIND OF BLUE’ FRI 30 - SAT 1 : COLIN TOWNS’ MASK ORCHESTRA PERFORMING ‘VISIONS OF MILES’ | Regular invites to drinks tastings and other special events in the jazz calendar OCTOBER | Priority information, advanced notice on acts appearing SUN 2: RSJO PRESENTS.. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron.