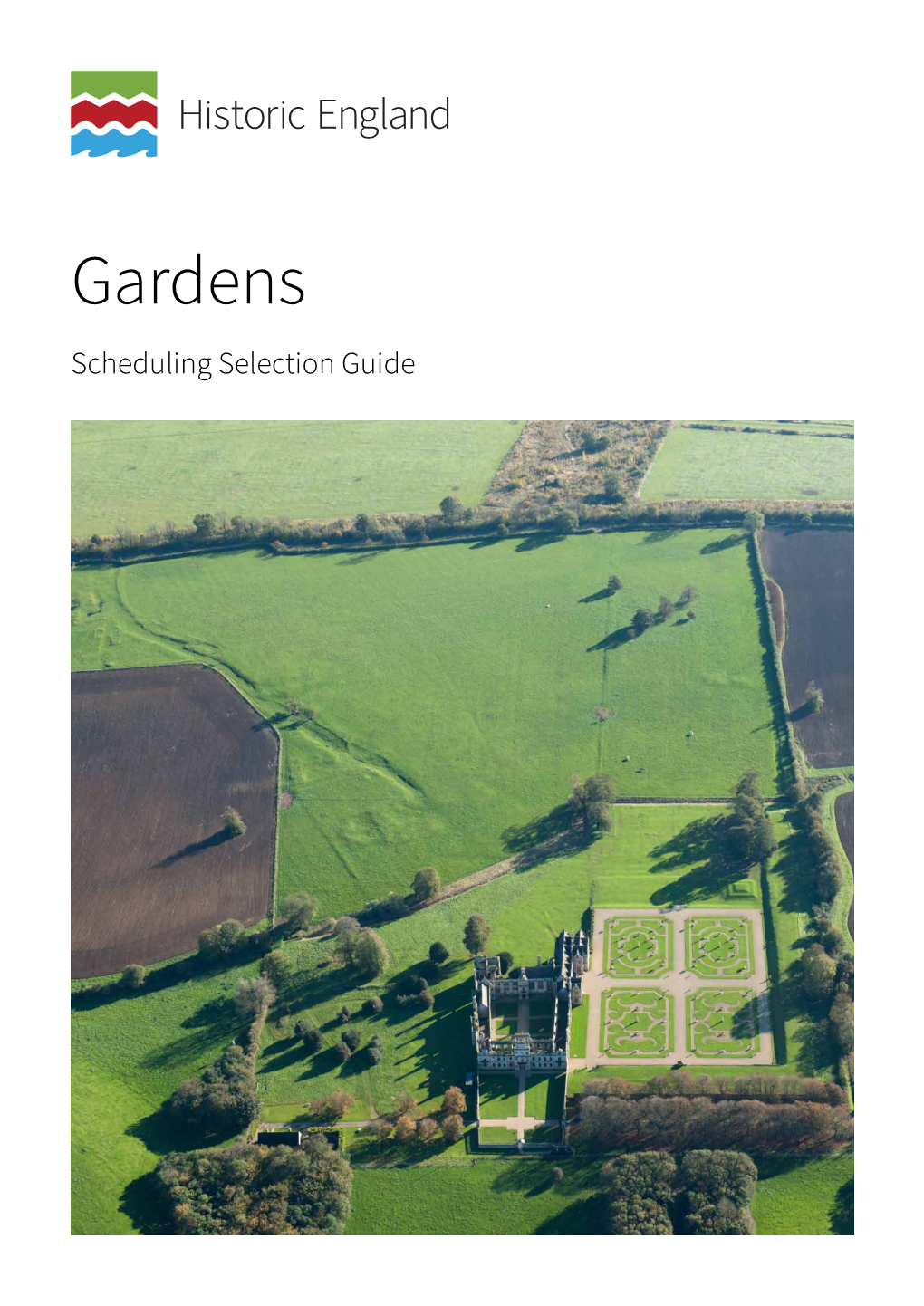

Gardens Scheduling Selection Guide Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape and Architecture COMMONWEALTH of AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969

702132/702835 European Architecture B landscape and architecture COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice garden scene from a C15th manuscript of the Roman de la Rose Christopher Thacker, The History of Gardens (Berkeley [California] 1979), p 87 Monreale Cathedral, Palermo, Sicily, 1176-82: cloisters of the Benedictine Monastery commercial slide RENAISSANCERENAISSANCE && MANNERISMMANNERISM gardens of the Villa Borghese, Rome: C17th painting J D Hunt & Peter Willis, The Genius of the Place: the English Landscape Garden 1620-1820 (London 1975), p 61 Villa Medici di Castello, Florence, with gardens as improved by Bernardo Buontalenti [?1590s], from the Museo Topografico, Florence Monique Mosser & Georges Teyssot [eds], The History of Garden Design: The Western Tradition from the Renaissance to the Present Day (London 1991 [1990]), p 39 Chateau of Bury, built by Florimund Robertet, 1511-1524, with gardens possibly by Fra Giocondo W H Adams, The French Garden 1500-1800 (New York 1979), p 19 Chateau of Gaillon (Amboise), begun 1502, with gardens designed by Pacello de Mercogliano Adams, The French Garden, p 17 Casino di Pio IV, Vatican gardens, -

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of- selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. This guide looks at buildings and other structures found in gardens, parks and indeed designed landscapes of all types from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century. -

The RHS Lindley Library IBRARY L INDLEY RHS, L

Occasional Papers from The RHS Lindley Library IBRARY L INDLEY RHS, L VOLUME NINE DECEMBER 2012 The history of garden history Cover illustration: Engraved illustration of the gardens at Versailles, from Les Jardins: histoire et description by Arthur Mangin (c.1825–1887), published in 1867. Occasional Papers from the RHS Lindley Library Editor: Dr Brent Elliott Production & layout: Richard Sanford Printed copies are distributed to libraries and institutions with an interest in horticulture. Volumes are also available on the RHS website (www. rhs.org.uk/occasionalpapers). Requests for further information may be sent to the Editor at the address (Vincent Square) below, or by email (brentelliottrhs.org.uk). Access and consultation arrangements for works listed in this volume The RHS Lindley Library is the world’s leading horticultural library. The majority of the Library’s holdings are open access. However, our rarer items, including many mentioned throughout this volume, are fragile and cannot take frequent handling. The works listed here should be requested in writing, in advance, to check their availability for consultation. Items may be unavailable for various reasons, so readers should make prior appointments to consult materials from the art, rare books, archive, research and ephemera collections. It is the Library’s policy to provide or create surrogates for consultation wherever possible. We are actively seeking fundraising in support of our ongoing surrogacy, preservation and conservation programmes. For further information, or to request an appointment, please contact: RHS Lindley Library, London RHS Lindley Library, Wisley 80 Vincent Square RHS Garden Wisley London SW1P 2PE Woking GU23 6QB T: 020 7821 3050 T: 01483 212428 E: library.londonrhs.org.uk E : library.wisleyrhs.org.uk Occasional Papers from The RHS Lindley Library Volume 9, December 2012 B. -

The Idea of the Labyrinth

·THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH · THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages Penelope Reed Doob CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1990 by Cornell University First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 1992 Second paperback printing 2019 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8014-2393-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3845-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3846-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-3847-0 (epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress An open access (OA) ebook edition of this title is available under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by- nc-nd/4.0/. For more information about Cornell University Press’s OA program or to download our OA titles, visit cornellopen.org. Jacket illustration: Photograph courtesy of the Soprintendenza Archeologica, Milan. For GrahamEric Parker worthy companion in multiplicitous mazes and in memory of JudsonBoyce Allen and Constantin Patsalas Contents List of Plates lX Acknowledgments: Four Labyrinths xi Abbreviations XVll Introduction: Charting the Maze 1 The Cretan Labyrinth Myth 11 PART ONE THE LABYRINTH IN THE CLASSICAL AND EARLY CHRISTIAN PERIODS 1. -

Greenwood Gardens, Short Hills, New Jersey Judith B

A Garden of the Gods GREENWOOD GARDENS, SHORT HILLS, NEW JERSEY JUDITH B. TANKARD Nestled in an incomparable setting in northern New Jersey, about an hour’s commute from midtown Manhattan, is an extraordinary garden that combines the eVorts of two diVerent American families. Today, Greenwood Gardens, established as a nonprofit conservation organisation in 2003 by the descendant of the second owner, is a thriving nature conservancy that honours its unique historic gar- dens. In the early twentieth century, Joseph P. Day established a home and private pleasure grounds named Pleasant Days that was a family getaway from Day’s bustling real-estate oYce in New York City. He assembled a team of experts to design and decorate his lavish storybook house and gardens. In 1950, when the estate was in a sorry state of disrepair after Day’s death, it was rescued by Peter J. Blanchard, Jr., a lawyer and budding gentleman farmer, as a weekend retreat to enjoy with his wife, Adelaide. The fanciful mansion, which had fallen on hard times, had to be demolished, but the gardens were not only saved, but embellished with a welcome layer of evergreen formality. In the course of his career as a multi-millionaire property auction- eer, Joseph P. Day ‘sold more real estate in and around New York City [including Coney Island] than any other single human being in the history of man’. During his lifetime, he grossed more than $1.5 billion in sales of private estates, oYce buildings, factories, government buildings and even NYC’s Third Avenue Railroad. -

Smc Garden Buildings Cover

www.shropshiremanufacturing.co.uk Contents Chalet Summerhouse Page 2 Corner Summerhouse Page 4 Hexagonal Summerhouse Page 6 Garden Gazebo Page 7 Garden Room Page 8 Hot Tub / Sunroom Page 10 Garden Office Page 11 Shepherds Hut Page 12 Pods Page 13 Garages Page 14 Miscellaneous Page 16 Planning Permission Page 17 Welcome Our garden buildings are available in an almost infinite range of sizes and designs from the humble summerhouse to the garden room designed as a work office, playroom, hobby centre or as extra accommodation for guests. We have been designing and building garden rooms for decades and have constructed literally thousands, each one different, designed with a specific purpose in mind. Some of our clients have an exact plan of their requirements and know precisely how the finished building should look, others have come to us with thoughts and a budget and we have worked with them to develop a design that would work for them. All our buildings are manufactured using quality timber sourced from sustainable resources. We work with a range of wood from softwood to larch, cedar and oak. You can specify unlined for the summer months or insulated and internally clad with a range of materials for a building to use all year round. Roofing materials range from heavy duty felt to slate, cedar shingles or felt tiles. We have designed and built summerhouses, garden offices, cricket pavilions, craft rooms, artists studios, oak garages, workshops, shepherds huts, glamping pods and retail units throughout the UK. Call in and see us for a chat -

Hampden House

Understanding Historic Parks and Gardens in Buckinghamshire The Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust Research & Recording Project HAMPDEN HOUSE January 2021 Roland Callingham Foundation HISTORIC SITE BOUNDARY Bucks Gardens Trust, Site Dossier: Hampden House, Wycombe District JANUARY 2021 2 INTRODUCTION Background to the Project This site dossier has been prepared as part of The Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust (BGT) Research and Recording Project, begun in 2014. This site is one of several hundred designed landscapes county‐wide identified by Bucks County Council in 1998 (including Milton Keynes District) as potentially retaining evidence of historic interest, as part of the Historic Parks and Gardens Register Review project carried out for English Heritage (now Historic England) (BCC Report No. 508). The list is not definitive and further parks and gardens may be identified as research continues or further information comes to light. Content BGT has taken the Register Review list as a sound basis from which to select sites for appraisal as part of its Research and Recording Project for designed landscapes in the historic county of Bucks (pre‐1974 boundaries). For each site a dossier is prepared by volunteers trained by BGT in appraising designed landscapes. Each dossier includes the following for the site: A site boundary mapped on the current Ordnance Survey to indicate the extent of the main part of the surviving designed landscape, also a current aerial photograph. A statement of historic significance based on the four Interests outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework and including an overview. A written description, derived from documentary research and a site visit, based on the format of Historic England Register of Parks & Gardens of special historic interest 2nd edn. -

Gardens and Tourism

GARDENS AND TOURISM For and beyond economic profit 1 Coordination Ana Duarte Rodrigues Authors Alexandra Gago da Câmara Ana Duarte Rodrigues António Lamas Antonio Perla de las Parras Celso Mangucci Desidério Batista Filipe Benjamim Ignacio Rodriguez Somovilla Jean-Paul Brigand Maria Isabel Donas Botto Nuno Oliveira Paulo Carvalho Susana Silva Victoria Soto Caba Design| Conception| Layout Maggy Victory Front cover photograph by Jean-Paul Brigand of Lugar Feliz Published by Centro de História da Arte e Investigação Artística da Universidade de Évora and Centro Interuniversitário de História das Ciências e da Tecnologia ISBN: 978-989-99083-5-2 2 GARDENS AND TOURISM For and beyond economic profit Ana Duarte Rodrigues Coordination CHAIA/CIUHCT 2015 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE by Ana Duarte Rodrigues, 7 PART I – GARDENS AND TOURISM: A HISTORIC AND WORLDWIDE PHENOMENON Maria Isabel Donas Botto Garden tourism in England: an early discovery, 11 Victoria Soto Caba and Antonio Perla de las Parras Vulnerable images: Toledo, the arid city and its hidden gardens, 27 PART II – THE CHALLENGES OF GARDENS AND LANDSCAPES FOCUSED ON TOURISM Desidério Batista Landscape and Tourism: a case-study of Cacela’s historic nucleus, situated in Ria Formosa natural park, Algarve, 49 Ana Duarte Rodrigues The Festival Garden at Ponte de Lima: a case of success, 63 Celso Mangucci and Alexandra Gago da Câmara Modern Hermits. The Azulejo and the functional transformation of monastic spaces in the Alentejo, 79 PART III – ECONOMIC GROWTH THROUGH HISTORIC GARDEN TOURISM AND PROBLEMS TO BE FACED Susana Silva and Paulo Carvalho The Portuguese (historic) gardens as strategic tourism resources in the 21st century. -

Kubota Garden Master Plan Update Kubota Garden 2019 Master Plan Update

2019 KUBOTA GARDEN MASTER PLAN UPDATE KUBOTA GARDEN 2019 MASTER PLAN UPDATE for Seattle Department of Parks & Recreation A and the Kubota Garden Foundation B C D by Jones & Jones Architects + Landscape Architects + Planners 105 South Main Street, Suite 300 E FG Seattle, Washington 98104 Cover Photo Credits: /VZOPKL>HUaLY A. KGF Photo #339 (1976) B. Jones & Jones (2018) C. Jones & Jones (2018) D. KGF Photo #19 (1959) E. KGF Photo #259 (1962) F. Jones & Jones (2018) G. Jones & Jones (2018) (YJOP[LJ[Z 206 624 5702 www.jonesandjones.com TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 4 I. INTRODUCTION. .. .6 VI. PREFERRED CONCEPT . .. .. .. .. ..40 SUPPORT FOR THE MASTER PLAN UPDATE . .5 Need for a Master Plan Update Guiding Principles Garden Mission History: Fujitaro Kubota's Life, Inspiration, and Garden Style History: Setting the Period of Significance II. PLANNING PROCESS . .10 Necklace of Ponds Kyōryoku - Collective Effort Japanese Garden Seeking Input The Mountainside Opportunities & Issues Visitor Experience III. HISTORY OF KUBOTA GARDEN. .12 Visitor Amenities Kubota Family Wayfinding and VisitorC irculation Hierarchy Kubota Gardening Company Visitor Center Post World War II Garden Improvements Transitioning from Garden to Park IV. SITE ANALYSIS. 16 VII. IMPLEMENTATION . 65 Neighborhood Context Phasing & Implementation Visitation Staffing Mapes Creek & Natural Areas Garden Arrival APPENDIX (Separate Document) The Garden Garden History Resources Events & Programming Workshops Summary Maintenance Area Open House(s) Summary V. GARDEN NEED . .36 KGF -

Historic-Gardens-Review-Nov18-2.Pdf

I An Unsung Arcadia A royal refuge with republican links deserves to be better known. ever before had I stayed in a hotel where there was As with many ancient properties, over the centuries a polite sign in the bathroom asking guests not to several gardens have been made at Hartwell, each being N let the bath overflow because water would damage 'improved' according to the fashion of the time and the the 18th-century stucco ceiling in the room below. We were whims and wealth of the owners . Some we know very little at Hartwell House, in Buckinghamshire, which is a National about- the mid-17th century gardens are mere smudges on Trust property- though not in quite the usual way. It is one a 1661 plan- bur at least three of them, all made in the of three beautiful houses which were saved from dereliction 18th century, are of historic interest and are well• by Richard Broyd to be run as hotels. The other two are documented. The earliest is a formal garden dated 1715-20, Middlethorpe in Yorkshire and Boddysgallen in Wales - and which was largely destroyed to make way for a pleasure all of them have fine gardens. In 2008 Richard Broyd garden created in 1759-60, to which a flower garden was donated the Historic House Hotels group to the National added in the closing years of the century. Trust, which continues to run them as luxury hotels whose Hartwell 's owners, from a natural son ofWilliam the profits help to support the organisation's conservation work. -

Download Corporate Brochure (PDF)

CULTURE AT ITS FINEST Credits Publisher and Editor: Mag. Klaus Panholzer, CEO / Director Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H. Concept: Mag.a Petra Reiner, Mag.a Evelyn Larcher Photos: © Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H. / Severin Wurnig, Alexander Eugen Koller, Stefan Joham, Reza Sarkari Design: Lumsden & Friends Printed by: Bösmüller Print Management ‘We act as an Imperial host, who courteously welcomes guests from Austria and all over the world to his stately homes, provides them with the best of entertainment and treats them as royalty. We rely on quality, responsibility and strong partnerships to ensure all-round success.’ Schönbrunn Group 1 2 Dear Readers, With Schönbrunn Palace, the Vienna Furniture Museum, the Sisi Museum in the Vienna Hofburg and the Schloss Hof Estate, the Schönbrunn Group administers the foremost attractions of Austria’s Imperial heritage. The revenue yielded is invested in the preser- vation and renovation of the cultural monuments, enabling us in consequence to contin- ue offering a unique experience to our visitors. Meanwhile, new initiatives will inspire people’s interest across the world for the Imperial heritage and world of the Habsburgs. This is only possible with competent and committed associates and co-workers, vision- ary advisory boards, and innovative cooperative and business partners. The essential factors here are an open entrepreneurial culture and mutual appreciation and respect. Accordingly, I would like to thank you for your interest and trust! We not only preserve and conserve, we also create, every day, through our endeavours and our work. So that every visit to our locations will be an unforgettable experience! Mag. -

A Polymath in Arcadia: Thomas Wright (1711-1786)

1 A POLYMATH IN ARCADIA: THOMAS WRIGHT (1711-1786) The name of Thomas Wright is chiefly remembered for achievement in the realms of astronomy and architecture but his contribution to English landscape has received limited attention by comparison despite association with over thirty notable locations. It might have been the existence of other eighteenth-century quasi-eminent Thomas Wrights which led him to adopt the appellation ‘Thomas Wright of Durham’ since Thomas Wright was certainly not an uncommon name in County Durham if tombstones in proximity to Wright’s are any indicator - indeed the present day bishop of that diocese is one Tom Wright. This essay will trace the emergence of Thomas Wright as a key contributor to eighteenth – century landscape architecture through designs uniquely imbued with significance derived from his polymathic passions. ‘THOMAS WRIGHT OF DURHAM’ Thomas Wright‟s ranking amongst his contemporaries in garden history has waxed and waned like the heavenly bodies whose progress he traced so diligently. It is fortuitous that the Journal that he kept for the first thirty-five years of his life has survived revealing how a largely self-taught polymath with a lifelong habit of application to the acquisition of knowledge became a tutor, companion and landscape advisor to a host of inter-connected families of note.1 Whilst this complex web of aristocratic genealogical association linking Wright to an extended galaxy of locations remains to be fully explored, his Journal together with commentary from his contemporaries,