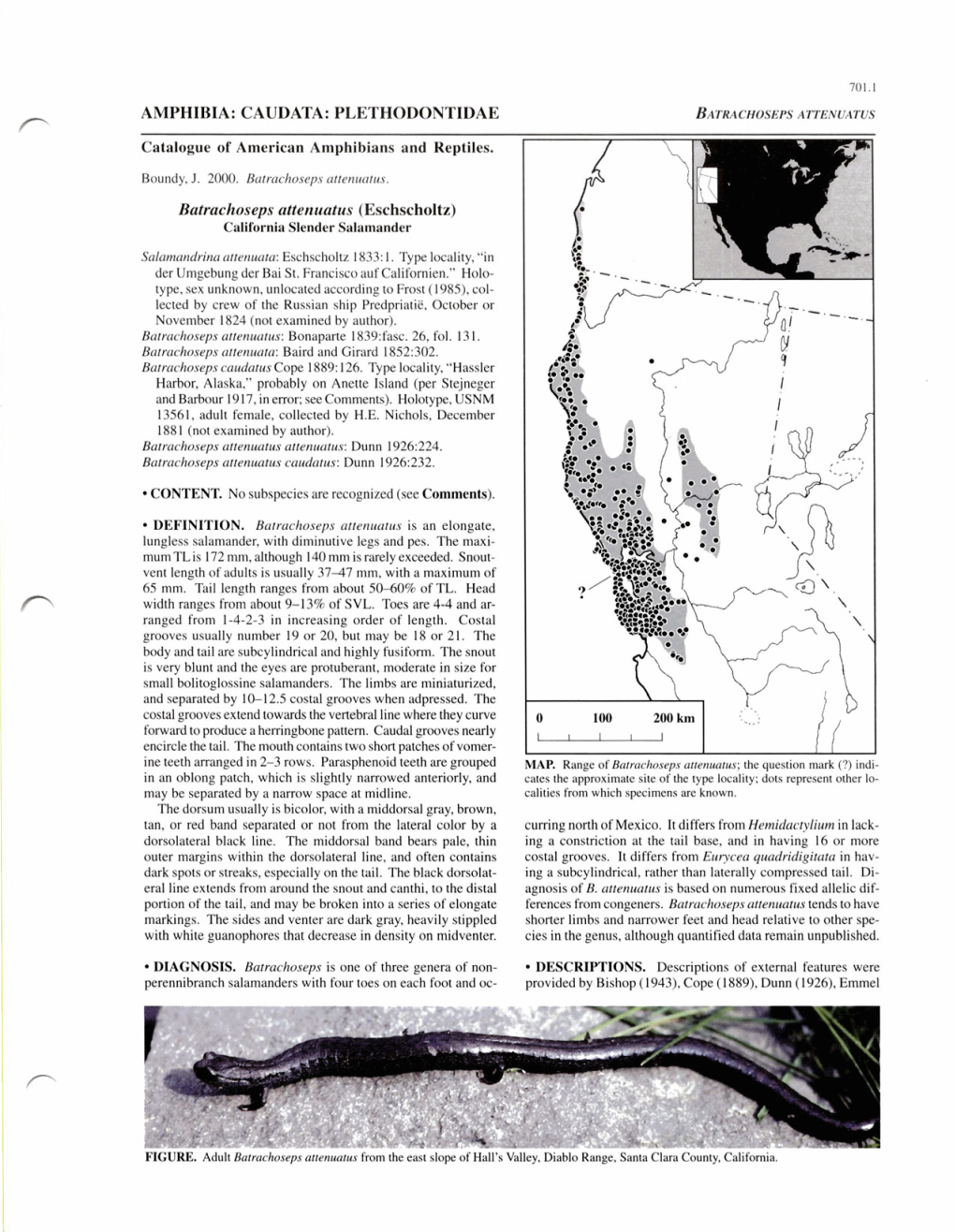

PLETHODONTIDAE Batrachoseps Attenuatus (Eschscholtz)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT for the LUCAS Creek PROJECT KERN

Biological Assessment- Lucas Creek Project BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT For the LUCAS Creek PROJECT KERN RIVER RANGER DISTRICT SEQUOIA NATIONAL FOREST Kern County, California PREPARED By:--J; �ATE: February 5, 2018 Nina Hemphi Forest Fish Biologist/Aquatic Ecologist and Watershed Manager This Biological Assessment analyzes the potential impacts associated with implementation of the Lucas Creek Project on federal endangered and threatened species as identified under the Endangered Species Act. The environmental analysis evaluates the preferred alternative. The Lucas Creek Project includes removal of dead and dying trees on 250 acres on Breckenridge Mountain. The project area is located in sections 23, 24, 25, & 26, township 28 south, range 31 east, Mount Diablo Base Meridian on the Kern River Ranger District of the Sequoia National Forest. The project surrounds the Breckenridge subdivision on Breckenridge Mountain approximately 25 miles southwest of the town of Lake Isabella in Kern County California. The intent of the Lucas Creek Project is to remove hazard trees along roads and properties adjoining the Breckenridge Subdivision. The project would also reduce fuels build-up to protect the community and the Lucas Creek upper and middle watershed from high-intensity fire. This will improve forest resilience and watershed health. This document is prepared in compliance with the requirements of FSM 2672.4 and 36 CFR 219.19. Biological Assessment- Lucas Creek Project I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this Biological Assessment (BA) is to review the potential effects of Lucas Creek Project on species classified as federally endangered and threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA, 1973). Federally listed species are managed under the authority of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the National Forest Management Act (NFMA; PL 94- 588). -

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group FAIRVIEW SLENDER SALAMANDER Batrachoseps bramei Family: PLETHODONTIDAE Order: CAUDATA Class: AMPHIBIA A073 Written by: T. Kucera, 1997 Updated by: CWHR Staff May 2013 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY Yearlong resident in the western slope of the southern Sierra Nevada. Individuals occur along streams and in moist wooded canyons in valley foothill riparian habitats, blue oak woodlands, and Sierra mixed conifer woodlands (Yanev 1978). Brame and Murray (1968) included salamanders from four disjunct regions, including the southern Sierra Nevada, in B. pacificus. Jennings and Hayes (1994) elevated the animals from the southern Sierra Nevada to specific status (B. relictus). Then, on the basis of DNA analyses (Jockusch 1996, Jockusch et al. 1998), the B. relictus complex was split out into four distinct species: B. relictus, B. regius, B. kawia and B. diabolicus. Jockusch et al. (2012) documented morphological and molecular data to support the recognition of B. bramei as a species distinct from B. relictus. SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Feeding probably occurs both above and below ground (Hendrickson 1954). Stebbins (1951) reported that a similar species, the pacific slender salamander (B. pacficus), fed on earthworms, small slugs, a variety of terrestrial arthropods including sowbugs and millipedes, and insects including collembolans, aphids, caterpillars, small beetles, beetle larvae, and ants. The fairview slender salamander probably eats a similar array of prey items. Cover: Members of the genus Batrachoseps do not usually excavate burrows. They rely on passages made by other animals, or produced by root decay or soil shrinkage (Yanev 1978). -

Sensitive Species of Snakes, Frogs, and Salamanders in Southern California Conifer Forest Areas: Status and Management1

Sensitive Species of Snakes, Frogs, and Salamanders in Southern California Conifer Forest Areas: Status and Management1 Glenn R. Stewart2, Mark R. Jennings3, and Robert H. Goodman, Jr.4 Abstract At least 35 species of amphibians and reptiles occur regularly in the conifer forest areas of southern California. Twelve of them have some or all of their populations identified as experiencing some degree of threat. Among the snakes, frogs, and salamanders that we believe need particular attention are the southern rubber boa (Charina bottae umbratica), San Bernardino mountain kingsnake (Lampropeltis zonata parvirubra), San Diego mountain kingsnake (L.z. pulchra), California red-legged frog (Rana aurora draytonii), mountain yellow-legged frog (R. muscosa), San Gabriel Mountain slender salamander (Batrachoseps gabrieli), yellow-blotched salamander (Ensatina eschscholtzii croceater), and large-blotched salamander (E.e. klauberi). To varying degrees, these taxa face threats of habitat degradation and fragmentation, as well as a multitude of other impacts ranging from predation by alien species and human collectors to reduced genetic diversity and chance environmental catastrophes. Except for the recently described San Gabriel Mountain slender salamander, all of these focus taxa are included on Federal and/or State lists of endangered, threatened, or special concern species. Those not federally listed as Endangered or Threatened are listed as Forest Service Region 5 Sensitive Species. All of these taxa also are the subjects of recent and ongoing phylogeographic studies, and they are of continuing interest to biologists studying the evolutionary processes that shape modern species of terrestrial vertebrates. Current information on their taxonomy, distribution, habits and problems is briefly reviewed and management recommendations are made. -

New Species of Slender Salamander, Genus Batrachoseps, from the Southern Sierra Nevada of California

Copeia, 2002(4), pp. 1016±1028 New Species of Slender Salamander, Genus Batrachoseps, from the Southern Sierra Nevada of California DAVID B. WAKE,KAY P. Y ANEV, AND ROBERT W. HANSEN Populations of robust salamanders belonging to the plethodontid salamander ge- nus Batrachoseps (subgenus Plethopsis) from the southern Sierra Nevada and adjacent regions represent a previously unknown species here described as Batrachoseps ro- bustus. The new species is robust, with a short trunk (17±18 trunk vertebrae) and well-developed limbs. It differs from its close geographic neighbor, Batrachoseps campi, in lacking patches of dorsal silvery iridophores and in having (typically) a lightly pigmented dorsal stripe, and from Batrachoseps wrighti in being more robust, having more trunk vertebrae, and in lacking conspicuous white spots ventrally. This species is widely distributed on the semiarid Kern Plateau of the southeastern Sierra Nevada and extends along the east slopes of the mountains into the lower Owens Valley; it also is found to the south in the isolated Scodie Mountains. It occurs at high elevations, from 1615±2800 m, in areas of low rainfall and high summer tem- peratures. HE slender salamanders, Batrachoseps, range ci®c. They occur in relatively extreme environ- T from the Columbia River in northern ments for terrestrial salamanders, in areas that Oregon (458339N) to the vicinity of El Rosario, are exceptionally hot and dry in the summer, Baja California Norte (308009N). These sala- and that have a short, unpredictable wet season manders were considered to display mainly in- with little rainfall. Some of them occur at high traspeci®c morphological variation, and for elevations that are under snow cover for several many years only two (Hendrickson, 1954) or months each year. -

Biology 2 Lab Packet for Practical 4

1 Biology 2 Lab Packet For Practical 4 2 CLASSIFICATION: Domain: Eukarya Supergroup: Unikonta Clade: Opisthokonts Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata – Chordates Subphylum: Urochordata - Tunicates Class: Amphibia – Amphibians Subphylum: Cephalochordata - Lancelets Order: Urodela - Salamanders Subphylum: Vertebrata – Vertebrates Order: Apodans - Caecilians Superclass: Agnatha Order: Anurans – Frogs/Toads Order: Myxiniformes – Hagfish Class: Testudines – Turtles Order: Petromyzontiformes – Lamprey Class: Sphenodontia – Tuataras Superclass: Gnathostomata – Jawed Vertebrates Class: Squamata – Lizards/Snakes Class: Chondrichthyes - Cartilaginous Fish Lizards Subclass: Elasmobranchii – Sharks, Skates and Rays Order: Lamniiformes – Great White Sharks Family – Agamidae – Old World Lizards Order: Carcharhiniformes – Ground Sharks Family – Anguidae – Glass Lizards Order: Orectolobiniformes – Whale Sharks Family – Chameleonidae – Chameleons Order: Rajiiformes – Skates Family – Corytophanidae – Helmet Lizards Order: Myliobatiformes - Rays Family - Crotaphytidae – Collared Lizards Subclass: Holocephali – Ratfish Family – Helodermatidae – Gila monster Order: Chimaeriformes - Chimaeras Family – Iguanidae – Iguanids Class: Sarcopterygii – Lobe-finned fish Family – Phrynosomatidae – NA Spiny Lizards Subclass: Actinistia - Coelocanths Family – Polychrotidae – Anoles Subclass: Dipnoi – Lungfish Family – Geckonidae – Geckos Class: Actinopterygii – Ray-finned Fish Family – Scincidae – Skinks Order: Acipenseriformes – Sturgeon, Paddlefish Family – Anniellidae -

Jockusch Et Al in 2012

Zootaxa 3190: 1–30 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Morphological and molecular diversification of slender salamanders (Caudata: Plethodontidae: Batrachoseps) in the southern Sierra Nevada of California with descriptions of two new species ELIZABETH L. JOCKUSCH1, IÑIGO MARTÍNEZ-SOLANO1,2, ROBERT W. HANSEN3, & DAVID B. WAKE4 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, 75 N. Eagleville Rd., U-3043, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Instituto de Investigación en Recursos Cinegéticos (IREC) (CSIC-UCLM-JCCM), Ronda de Toledo, s/n 13005 Ciudad Real, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 316333 Deer Path Lane, Clovis, CA 93619-9735, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 4Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 3101 Valley Life Sciences Building, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3160, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Slender salamanders of the genus Batrachoseps achieve relatively high diversity in the Kern Canyon region at the southern end of the Sierra Nevada of California through high turnover of species with small geographic ranges. The status of several populations of Batrachoseps in this region is enigmatic, and both morphological and molecular data have suggested that some populations do not belong to any of the currently recognized species. Identification of species in this region is com- plicated by the apparent extinction of Batrachoseps relictus in the vicinity of its type locality in the Lower Kern River Canyon. Here we analyze a comprehensive morphological dataset to evaluate diversity in the Kern River Canyon region. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Persistent Plethodontid Themes: Species, Phylogenies, and Biogeography Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8dg7n8h6 Journal Herpetologica, 73(3) ISSN 0018-0831 Author Wake, DB Publication Date 2017-09-01 DOI 10.1655/HERPETOLOGICA-D-16-00065.1 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Persistent Plethodontid Themes: Species, Phylogenies, and Biogeography Author(s): David B. Wake Source: Herpetologica, 73(3):242-251. Published By: The Herpetologists' League https://doi.org/10.1655/HERPETOLOGICA-D-16-00065.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1655/HERPETOLOGICA-D-16-00065.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Herpetologica, 73(3), 2017, 242–251 Ó 2017 by The Herpetologists’ League, Inc. Persistent Plethodontid Themes: Species, Phylogenies, and Biogeography 1 DAVID B. -

Desert Slender Salamander 5-Year Review

Desert Slender Salamander (Batrachoseps major aridus) (=B. aridus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Desert slender salamander (Batrachoseps major aridus). Photo credit: Mario Garcia-Paris U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office Carlsbad, CA January 31, 2014 2014 5-year Review for Desert Slender Salamander 5-YEAR REVIEW Desert Slender Salamander (Batrachoseps major aridus) I. GENERAL INFORMATION Purpose of 5-year Reviews: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is required by section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (Act) to conduct a status review of each listed species at least once every 5 years. The purpose of a 5-year review is to evaluate whether or not the species’ status has changed since it was listed (or since the most recent 5-year review). Based on the 5-year review, we recommend whether the species should be removed from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife, be changed in status from endangered to threatened, or be changed in status from threatened to endangered. Our original listing of a species as endangered or threatened is based on the existence of threats attributable to one or more of the five threat factors described in section 4(a)(1) of the Act, and we must consider these same five factors in any subsequent consideration of reclassification or delisting of a species. In the 5-year review, we consider the best available scientific and commercial data on the species, and focus on new information available since the species was listed or last reviewed. If we recommend a change in listing status based on the results of the 5-year review, we must propose to do so through a separate rule-making process defined in the Act that includes public review and comment. -

California Rare & Endagered Amphibians

Santa Cruz long- Ambystoma toed salamander macrodactylum croceum State Endangered 1971 Fully Protected Federal Endangered 1967 General Habitat: The Santa Cruz long-toed salamander occurs in coastal woodlands and upland chaparral near the ponds and freshwater marshes in which it breeds. This salamander spends a significant portion of its life underground in the burrows of small mammals such as mice, gophers, and moles. It can also be found among the roots of plants in upland and wooded areas. At the onset of the rainy season (November or December), adults begin their annual nocturnal migration from upland habitat to the breeding ponds. As the ponds dry (May-August), young salamanders move at night away from the ponds to subterranean or vegetative cover. Description: The Santa Cruz long toed salamander is a relatively small (four to 12 inches), black salamander with yellow orange blotches. Preliminary data from a Doctoral study by Wes Savage at U. C. Davis appears to indicate that the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander is a distinct species. Status: The Santa Cruz long-toed salamander is a relict form of a species that was more widespread in California during the last glacial period, 10,000 to 20,000 years ago. It became isolated along the coast as a result of climatic changes. Much of its habitat has been lost to urbanization, agriculture, and highway construction. Currently known from 14 sites in coastal areas of Monterey and Santa Cruz Counties, these populations comprise three metapopulations that inhabit ponds or sloughs and the surrounding uplands. Today, the metapopulations are separated by the Pajaro River and Elkhorn Slough and extensive areas of agriculture. -

This PDF Guide

Urban Nature Research Center SCAVENGER HUNT LET’S LOOK FOR ALLIGATOR LIZARDS Help us study lizard behavior in your own backyard! With days getting longer and temperatures increasing, we are entering alligator lizard mating season, and we need your help to study their mating activity. In urban areas, including the Greater Los Angeles Area, alligator lizards are the most widespread lizards. They can be found eating grubs and slugs in compost bins; hunting for spiders, caterpillars, and crickets in gardens; and sometimes taking an accidental stroll through a living room or garage. During mating season, males search out females. The male bites the female on her neck or head and may hold her this way for several days. Like most other species on this planet, we still have much to learn about them. In fact, just five years ago, there were only three instances of this rarely documented behavior reported in the scientific literature. Today, thanks to the help of our community scientists (i.e. people like you!), the Museum has now gathered over 400 observations–the largest dataset ever on lizard mating! But, we still need more. So get outside, soak in some spring sunshine, enjoy nature, and of course maintain social distancing– meaning that others should be looking for alligator lizards more than 6 feet away from you! WHEN TO LOOK? In Southern California, most of the breeding activity is between mid March and late April. This year, the season has been delayed by our rainy March, and mating pairs should be found in coastal Southern California through early May, with mating in more northern and higher elevation locations throughout May and June. -

Validation of the Oregon Slender Salamander Habitat Suitability Model and Map for the West Slope of the Oregon Cascade Range

Validation of the Oregon slender salamander habitat suitability model and map for the west slope of the Oregon Cascade Range Nobuya Suzuki 1-1060 Southgate Street, Victoria, BC V8B 2Z2 Canada Deanna H. Olson Pacific Northwest Research Station, 3200 SW Jefferson Way, Corvallis, OR 97331 July 26, 2012 ABSTRACT Conservation of rare species with small geographic ranges, such as the Oregon slender salamander (Batrachoseps wrighti), is a concern for conservationists and managers who face challenges of balancing multiple-use objectives of stakeholders in rapidly changing environment. To accommodate the conservation effort for Oregon slender salamanders in the west slope of the Oregon Cascade Range on the federal land, we developed a landscape habitat suitability model using a generalized additive model (GAM) approach and projected four habitat suitability classes (low, moderately low, moderate, and high) onto a map. Herein, we assessed the applicability of the habitat suitability map and the performance of the GAM-based habitat suitability model using 2009 field validation data. The field validation data assessed salamander presence using a standard survey protocol at a stratified random sample of 84 sites, using the strata of the four habitat suitability classes. A large proportion (76%) of Oregon slender salamander detection sites fell within either the high or moderate habitat suitability class. A fair amount (37%) of non-detection sites were also in these 2 upper classes of habitat suitability probably because either not all suitable habitats were occupied or it is inherently difficult to detect a rare species, such as the Oregon slender salamander, even if it is present. Zero-inflated negative binomial regression analyses along with 95% confidence intervals verified that significantly high non- detection rates of Oregon slender salamanders were associated with the low habitat suitability class, whereas significantly high detection rates were associated with the moderate and high habitat suitability classes.