AZERBAIJAN: Elshan Mustafaoglu and Menevi Saflig Devet ̶ A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Caucasus Globalization

Volume 6 Issue 2 2012 1 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies Conflicts in the Caucasus: History, Present, and Prospects for Resolution Special Issue Volume 6 Issue 2 2012 CA&CC Press® SWEDEN 2 Volume 6 Issue 2 2012 FOUNDEDTHE CAUCASUS AND& GLOBALIZATION PUBLISHED BY INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS Registration number: M-770 Ministry of Justice of Azerbaijan Republic PUBLISHING HOUSE CA&CC Press® Sweden Registration number: 556699-5964 Registration number of the journal: 1218 Editorial Council Eldar Chairman of the Editorial Council (Baku) ISMAILOV Tel/fax: (994 12) 497 12 22 E-mail: [email protected] Kenan Executive Secretary (Baku) ALLAHVERDIEV Tel: (994 – 12) 596 11 73 E-mail: [email protected] Azer represents the journal in Russia (Moscow) SAFAROV Tel: (7 495) 937 77 27 E-mail: [email protected] Nodar represents the journal in Georgia (Tbilisi) KHADURI Tel: (995 32) 99 59 67 E-mail: [email protected] Ayca represents the journal in Turkey (Ankara) ERGUN Tel: (+90 312) 210 59 96 E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Nazim Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) MUZAFFARLI Tel: (994 – 12) 510 32 52 E-mail: [email protected] (IMANOV) Vladimer Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Georgia) PAPAVA Tel: (995 – 32) 24 35 55 E-mail: [email protected] Akif Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) ABDULLAEV Tel: (994 – 12) 596 11 73 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 6 IssueMembers 2 2012 of Editorial Board: 3 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Zaza D.Sc. -

Azerbaijans Regional Role September 2013

Azerbaijan’s Regional Role Iran and Beyond By Richard Weitz September 2013 Azerbaijan’s Regional Role • • • Azerbaijan’s Regional Role Iran and Beyond TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................... 2 AZERBAIJAN’S GROWING GLOBAL INFLUENCE ..................................................................................... 5 EMPOWERING RELIGIOUS TOLERANCE .................................................................................................. 11 MANAGING IRAN'S REGIONAL AMBITIONS ......................................................................................... 20 IRAN'S AZERBAIJANI MINORITY ......................................................................................................................... 21 CURRENT TENSIONS ............................................................................................................................................ 23 CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................................................................... 33 Executive Summary 1 Azerbaijan’s Regional Role • • • Executive Summary The Republic of Azerbaijan, a close U.S. ally since Azerbaijanis regained their independence following the Soviet Union’s collapse, has become a prominent role model for Muslim-majority nations seeking to manage religious and ethnic differences in a harmonious and productive manner. Thanks to its secular -

Shrines and Sovereigns: Life, Death, and Religion in Rural Azerbaijan

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2011;53(3):654–681. 0010-4175/11 $15.00 # Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History 2011 doi:10.1017/S0010417511000284 Shrines and Sovereigns: Life, Death, and Religion in Rural Azerbaijan BRUCE GRANT New York University Shrines fill the Eurasian land mass. They can be found from Turkey in the west to China in the east, from the Arctic Circle in the north to Afghanistan in the south. Between town and country, they can consist of full-scale architectural complexes, or they may compose no more than an open field, a pile of stones, a tree, or a small mausoleum. They have been at the centers and periph- eries of almost every major religious tradition of the region: Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism. Yet in the formerly socialist world, these places of pilgrimage have something even more in common: they were often cast as the last bastions of religious observance when churches, mosques, temples, and synagogues were sent crashing to the ground in rapid succession across the twentieth century. In this essay I draw attention to a number of such shrines in the south Cau- casus republic of Azerbaijan. My goal is not to celebrate these settings for their promotion of an alternative route to religiosity under communist rule, as many have done before me, but rather to consider the ways in which the very popular attachments to shrines over so many centuries offer a window onto the plas- ticity and porosity of political, religious, and social boundaries in a world area that otherwise became better known over the twentieth century for its leaders of steel, curtains of iron, and seemingly immobilized citizens. -

Religious Aspects of Bilingualism in Azerbaijan

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 40 Issue 6 Article 5 8-2020 Religious Aspects of Bilingualism in Azerbaijan Malahat Veliyeva Azerbaijan University of Languages, Baku Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Islamic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Veliyeva, Malahat (2020) "Religious Aspects of Bilingualism in Azerbaijan," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 40 : Iss. 6 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol40/iss6/5 This Thirty-Year Anniversary since the Fall of Communism is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELIGIOUS ASPECT OF BILINGUALISM IN AZERBAIJAN In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful... By Malahat Veliyeva Malahat Veliyeva is an Associate Professor at the Department of English Linguistics at Azerbaijan University of Languages in Baku. She did her PhD in Germanic languages in 2008 and started the post-doctorate degree in Sociolinguistics in 2012. Her area of interest is also multiculturalism and religious studies. She was a SUSI scholar awarded by the scholarship of the US Department of State in 2019. She has three publications on General Linguistics. Email: [email protected] Introduction Azerbaijan is one of the former countries of the Union of Soviet Socialistic Republics (the USSR) that lost its independence in 1920 when the Russian XI Red Army brutally intervened in the country and imposed the Soviet regime throughout Azerbaijan. -

Genocide and Deportation of Azerbaijanis

GENOCIDE AND DEPORTATION OF AZERBAIJANIS C O N T E N T S General information........................................................................................................................... 3 Resettlement of Armenians to Azerbaijani lands and its grave consequences ................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Iran ........................................................................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Turkey ................................................................................... 8 Massacre and deportation of Azerbaijanis at the beginning of the 20th century .......................... 10 The massacres of 1905-1906. ..................................................................................................... 10 General information ................................................................................................................... 10 Genocide of Moslem Turks through 1905-1906 in Karabagh ...................................................... 13 Genocide of 1918-1920 ............................................................................................................... 15 Genocide over Azerbaijani nation in March of 1918 ................................................................... 15 Massacres in Baku. March 1918................................................................................................. 20 Massacres in Erivan Province (1918-1920) ............................................................................... -

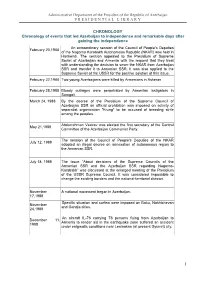

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I a L L I B R a R Y

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CHRONOLOGY Chronology of events that led Azerbaijan to independence and remarkable days after gaining the independence An extraordinary session of the Council of People's Deputies February 20,1988 of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Republic (NKAR) was held in Hankendi. The session appealed to the Presidium of Supreme Soviet of Azerbaijan and Armenia with the request that they treat with understanding the decision to sever the NKAR from Azerbaijan SSR and transfer it to Armenian SSR. It was also applied to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR for the positive solution of this issue. February 22,1988 Two young Azerbaijanis were killed by Armenians in Askeran February 28,1988 Bloody outrages were perpetrated by Armenian instigators in Sumgait March 24, 1988 By the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan SSR an official prohibition was imposed on activity of separatist organization "Krung" to be accused of breeding strife among the peoples. Abdurrahman Vezirov was elected the first secretary of the Central May 21,1988 Committee of the Azerbaijan Communist Party. The session of the Council of People's Deputies of the NKAR July 12, 1988 adopted an illegal decree on annexation of autonomous region to the Armenian SSR. July 18, 1988 The issue “About decisions of the Supreme Councils of the Armenian SSR and the Azerbaijan SSR regarding Nagorno- Karabakh” was discussed at the enlarged meeting of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Council. -

State Report Azerbaijan

ACFC/SR(2002)001 ______ REPORT SUBMITTED BY AZERBAIJAN PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 1 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES ______ (Received on 4 June 2002) _____ TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I............................................................................................................................................ 3 II. Aggression of the Republic of Armenia against the Republic of Azerbaijan..................... 9 III. Information on the form of the State structure.................................................................. 12 IV. Information on status of international law in national legislation .................................... 13 V. Information on demographic situation in the country ...................................................... 13 VI. Main economic data - gross domestic product and per capita income ............................. 15 VII. State’s national policy in the field of the protection of the rights of persons belonging to minorities ...................................................................................................................................... 15 VIII. Population awareness on international treaties to which Azerbaijan is a party to........ 16 P A R T II..................................................................................................................................... 18 Article 1 ........................................................................................................................................ 18 Article -

Social Status of 'Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi' in Present-Day Azerbaijan

Social status of ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’ in present-day Azerbaijan ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’ as counter-balance Year: 2015 Place of fieldwork: Republic of Azerbaijan Name:Ko Iwakura Keywords: Azerbaijan, Control policy on Islam, ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’, Minority Sunni, Counter-balance Research background Azerbaijan is a country comprising approximately 70% Shia and 25% Sunni Muslims, while the national majority are Azerbaijanis (descended from the Turkic people). We can see the authority of secularism through the government’s control policy on Islam and ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’, which is a society organization that controls Ulama (Islamic law scholars) and mosques. In fact, when walking around an Azerbaijani town, we can observe women not wearing headscarves, alcohol and pork being sold and consumed, and other examples of non-Islamic practices. Conversely, despite government and ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’ policies, uncontrollable Islamic social organizations are active. To limit them, laws and police powers are exercised to manage the current situation. Research purpose and aim Prior research on the management of uncontrollable Islamic social organizations has either neglected or ignored the roles of the government and ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’. Unlike prior research, this study focuses on the policies of ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’ on Islam and social status. Focusing on these points, it is possible to provide the government’s perspectives, rather than only the perspectives from outside the government, on the nature of Islam in Azerbaijan. Furthermore, I consider that this research can contribute not only to policies in Azerbaijan but also to enhancing understanding of the relationship between Islam and the governments of former Soviet and socialist bloc nations. -

REPUBLIC of AZERBAIJAN on the Rights of the Manuscript ABSTRACT

REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN On the rights of the manuscript ABSTRACT of the dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy THE THEORY OF MAHDISM IN THE WORLD RELIGIONS Speciality: 7213.01 – Religious studies Field of science: Philosophy Applicant: Elnur Karim Mustafayev Baku -2021 The dissertation work was performed at the "Religion and history of public opinion" department of the Institute of Oriental Studies named after Z.M.Bunyadov of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences. Scientific supervisor: Doctor of Philological Sciences, academic Vasim Mammadali Mammadaliyev Doctor of Philosophical Science, professor Sakit Yahya Huseynov Offical opponents: Doctor of Philological Sciences, professor Nasrulla Naib Mammadov Doctor of Philosophy in Theology, Associate Professor Elnura Akif Azizova Doctor of Philosophy in Theology, Associate Professor Shahlar Shahbaz Sharifov 2 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE WORK Relevance and development of the topic. Attitudes towards historical events, ancient national and spiritual heritage, especially religious beliefs have always been a topical issue for the social sciences and humanities. Religious beliefs and national- cultural heritage as a whole are considered to be the spiritual and intangible wealth of every nation. Mythological imagery, oral and written folklore, material cultural monuments, ancient stone chronicles, religious beliefs and traditions are all evidence of the existence of a nation as a whole. The different cultures, traditions, and religious beliefs we observe in different nations are the result of the way of life and the way of thinking that people have formed over a long period of time. Therefore, if there is a sharp turn in the destiny of each nation, the study of cultural and historical heritage, traditions and religious beliefs becomes one of the most important issues for the people to determine their own path of development. -

Problems of Muslim Belief in Azerbaijan: Historical and Modern Realities

ISSN 2707-4013 © Nariman Gasimoglu СТАТТІ / ARTICLES e-mail: [email protected] Nariman Gasimoglu. Problems of Muslim Belief іn Azerbaijan: Historical аnd Modern Realities. Сучасне ісламознавство: науковий журнал. Острог: Вид-во НаУОА, 2020. DOI: 10.25264/2707-4013-2020-2-12-17 № 2. C. 12–17. Nariman Gasimoglu PROBLEMS OF MUSLIM BELIEF IN AZERBAIJAN: HISTORICAL AND MODERN REALITIES Religiosity in Azerbaijan, the country where vast majority of population are Muslims, has many signs different to what is practiced in other Muslim countries. This difference in the first place is related to the historically established religious mentality of Azerbaijanis. Worth noting is that history of this country with its Shia Muslims majority and Sunni Muslims minority have registered no serious incidents or confessional conflicts and clashes either on the ground of inter-sectarian confrontation or between Muslim and non-Muslim population. Azerbaijan has never had anti-Semitism either; there has been no fact of oppression of Jewish people living in Azerbaijan for many centuries. One of the interesting historic facts is that Molokans (ethnic Russians) who have left Tsarist Russia when challenged by religious persecution and found asylum in neighborhoods of Muslim populated villages of Azerbaijan have been living there for about two hundred years and never faced problems as a religious minority. Besides historical and political reasons, this should be related to tolerance in the religious mentality of Azerbaijanis as well. Features of religion in Azerbaijan: historical context Most of the people living in Azerbaijan were devoted to Tengriism (Tengriism had the most important place in the old belief system of ancient Turks), Zoroastrianism and Christianity before they embraced Islam. -

Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture Historical Section

RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION Prepared by: Sabri Jarrar András Riedlmayer Jeffrey B. Spurr © 1994 AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION BIBLIOGRAPHIC COMPONENT Historical Section, Bibliographic Component Reference Books BASIC REFERENCE TOOLS FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE This list covers bibliographies, periodical indexes and other basic research tools; also included is a selection of monographs and surveys of architecture, with an emphasis on recent and well-illustrated works published after 1980. For an annotated guide to the most important such works published prior to that date, see Terry Allen, Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass., 1979 (available in photocopy from the Aga Khan Program at Harvard). For more comprehensive listings, see Creswell's Bibliography and its supplements, as well as the following subject bibliographies. GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND PERIODICAL INDEXES Creswell, K. A. C. A Bibliography of the Architecture, Arts, and Crafts of Islam to 1st Jan. 1960 Cairo, 1961; reprt. 1978. /the largest and most comprehensive compilation of books and articles on all aspects of Islamic art and architecture (except numismatics- for titles on Islamic coins and medals see: L.A. Mayer, Bibliography of Moslem Numismatics and the periodical Numismatic Literature). Intelligently organized; incl. detailed annotations, e.g. listing buildings and objects illustrated in each of the works cited. Supplements: [1st]: 1961-1972 (Cairo, 1973); [2nd]: 1972-1980, with omissions from previous years (Cairo, 1984)./ Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography, ed. Terry Allen. Cambridge, Mass., 1979. /a selective and intelligently organized general overview of the literature to that date, with detailed and often critical annotations./ Index Islamicus 1665-1905, ed. -

Yearbook of Muslims in Europe the Titles Published in This Series Are Listed at Brill.Com/Yme Yearbook of Muslims in Europe Volume 4

Yearbook of Muslims in Europe The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/yme Yearbook of Muslims in Europe Volume 4 Editor-in-Chief Jørgen S. Nielsen Editors Samim Akgönül Ahmet Alibašić Egdūnas Račius LEIDEN • boSTON 2012 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1877-1432 ISBN 978-90-04-22521-3 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-23449-9 (e-book) Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS The Editors ........................................................................................................ ix Editorial Advisers ...........................................................................................