Beware the White Rabbit: Tim Burton's Alice in Wonderland and A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Takes Alice to a Very Different Wonderland November 4, 2009 | 5:43 Am

Hero Complex For your inner fanboy 'Looking Glass Wars' takes Alice to a very different Wonderland November 4, 2009 | 5:43 am The rabbit hole is getting crowded again. It’s been 144 years since Lewis Carroll introduced the world to an inquisitive girl named Alice, but her surreal adventures still resonate – Tim Burton’s “Alice in Wonderland” arrives in theaters in March and next month on SyFy it's “Alice,” a modern-day reworking of the familiar mythology with a cast led by Kathy Bates and Tim Curry. And then there’s “The Looking Glass Wars,” the series of bestselling novels by Frank Beddor that takes the classic 19th century children’s tale off into a truly unexpected literary territory – the battlefields of epic fantasy. The series began in 2006 and Beddor’s third “Looking Glass Wars” novel, “ArchEnemy,” just hit stores in October, as did a tie-in graphic novel called “Hatter M: Mad with Wonder.” Beddor said it’s intriguing to see other creators at play in the same literary playground. “It’s amazing how many directions it’s been taken in,” Beddor said of Carroll’s enduring creations. “There’s something so rich and magical and whimsical about the original story and the characters and then there’s all those dark under-themes. Artists get inspired and they keep redefining it for a contemporary audience.” Indeed, creative minds as diverse as Walt Disney, the Jefferson Airplane, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Tom Petty, the Wachowski Brothers, Tom Waits and American McGee have adapted Carroll’s tale or borrowed memorably from its imagery. -

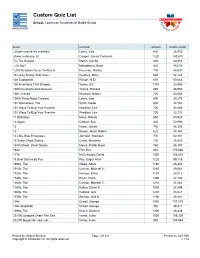

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Coachman Fundamental Middle School MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® WORD COUNT ¿Quién cuenta las estrellas? Lowry, Lois 680 26,950 último mohicano, El Cooper, James Fenimore 1220 140,610 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 40,955 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 98,676 1,000 Reasons Never To Kiss A Freeman, Martha 790 58,937 10 Lucky Things That Have Hershey, Mary 640 52,124 100 Cupboards Wilson, N. D. 650 59,063 100 Inventions That Shaped... Yenne, Bill 1370 33,959 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 38,950 1001 Cranes Hirahara, Naomi 720 43,080 100th Thing About Caroline Lowry, Lois 690 30,273 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 44,767 101 Ways To Bug Your Parents Wardlaw, Lee 700 37,864 101 Ways To Bug Your Teacher Wardlaw, Lee 700 52,733 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 650 50,929 12 Again Corbett, Sue 800 52,996 13 Howe, James 740 56,355 13 Brown, Jason Robert 620 38,363 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 770 62,401 13 Scary Ghost Stories Carus, Marianne 730 25,560 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 760 36,397 1632 Flint, Eric 650 175,646 1776 McCullough, David 1300 105,034 18 Best Stories By Poe Poe, Edgar Allan 1220 99,118 1900s, The Woog, Adam 1160 26,484 1910s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1280 29,561 1920s, The Hanson, Erica 1170 28,812 1930s, The Press, Petra 1300 27,749 1940s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1210 31,665 1950s, The Kallen, Stuart A. -

The Summer Reading Assignment Will Be Counted As Three Homework Grades (One Grade Per Book Read) and Will Be Due on August 23, 2019

Assignment Share one of the following with your teacher: • SCCPSS Reading log (Use your own paper for the response if you need more space) • myOn on-line reading report – free online reading offered by Get Georgia Reading • Copy of completed Barnes & Noble reading log (3 titles required for SCCPSS credit) • Copy of completed Live Oaks “A Universe of Stories” Early Literacy or Kids & Teens Activity Log Summer Reading for students entering Kindergarten is recommended, but not required. No grades will be given to kindergarten students. Students entering 1st Grade through 5th Grade this fall should read 3 books that fall within their Lexile range, from 100 points below to 50 points above their Lexile score. The Lexile score is found on the MAP reports, which were sent home to parents. Students are strongly encouraged to read at least one piece of informational (non-fiction) text over the summer. Georgia standards place a strong emphasis on informational text as students are prepared for success in college and career reading. Note: If your child’s Lexile score exceeds that of the Grade Level Lexile Band, then he or she should read texts either within his or her Lexile range, or within the appropriate Grade Level Lexile Band as outlined here. A Lexile measure is a good starting point for selecting books but should never be the only factor. The Summer Reading Assignment will be counted as three homework grades (one grade per book read) and will be due on August 23, 2019. Some titles are suggested below, or students may visit www.lexile.com to find their own books in their Lexile range. -

The Secularization of the Repertoire of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, 1949-1992

THE SECULARIZATION OF THE REPERTOIRE OF THE MORMON TABERNACLE CHOIR, 1949-1992 Mark David Porcaro A dissertation submitted to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music (Musicology) Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: Thomas Warburton Reader: Severine Neff Reader: Philip Vandermeer Reader: Laurie Maffly-Kipp Reader: Jocelyn Neal © 2006 Mark David Porcaro ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARK PORCARO: The Secularization of the Repertoire of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, 1949-1992 (Under the direction of Thomas Warburton) In 1997 in the New Yorker, Sidney Harris published a cartoon depicting the “Ethel Mormon Tabernacle Choir” singing “There’s NO business like SHOW business...” Besides the obvious play on the names of Ethel Merman and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, the cartoon, in an odd way, is a true-to-life commentary on the image of the Salt Lake Mormon Tabernacle Choir (MTC) in the mid-1990s; at this time the Choir was seen as an entertainment ensemble, not just a church choir. This leads us to the central question of this dissertation, what changes took place in the latter part of the twentieth century to secularize the repertoire of the primary choir for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS)? In the 1860s, when the MTC began, its sole purpose was to perform for various church meetings, in particular for General Conference of the LDS church which was held in the Tabernacle at Temple Square in Salt Lake City. From the beginning of the twentieth century and escalating during the late 1950s to the early 1960s, the Choir’s role changed from an in-house choir for the LDS church to a choir that also fulfilled a cultural and entertainment function, not only for the LDS church but also for the American public at large. -

KNTR Book List by NAME 108010:Layout 1.Qxd

Official Book List Kids Need to Read works to create a culture of reading for children by providing inspiring books to under-funded schools, libraries, and literacy programs across the United States, especially those serving disadvantaged children. It's oddly terrifying for me to consider the years during my childhood before I discovered reading. The world was a duller place, less ALIVE. The transformation happened when a gifted teacher knew which story to give me. To this day, I can't explain why discovering fantasy novels made me come to life, but I changed in a few brief months from a mediocre student to top of my class. All because of a book. Perhaps it was because I'd discovered something to care about, something that was ME. Novels aren't just happy escapes; they are slivers of people's souls, nailed to the pages, dripping ink from veins of wood pulp. Reading the right one at the right time can make all the difference. – Brandon Sanderson, Alcatraz and the Evil Librarians Series Fiction Preschoolers (Ages 0-4) Ferri, Francesca – Peek-A-Boo Foley, Greg – Thank You Bear Foley, Greg – Don’t Worry Bear Foley, Greg – Good Luck Bear Katz, Karen – Where is Baby’s Belly Button? Morgan, Michaela & Cartlidge, Michelle – Brave Mouse Portis, Antoinette – Not A Box Portis, Antoinette – Not A Stick Ringgold, Faith – Cassie’s Word Quilt Seeger, Laura Vaccaro – First the Egg Children (Ages 5-7) Choi, Yangsook – The Name Jar De Serranno, Daniel – Scare Me. Beware Me! Dewdney, Anna – Llama Llama series (3 titles) Llama Llama Red Pajama Llama Llama Mad at Mama Llama Llama Misses Mama French, Jackie & Whatley, Bruce – Diary of a Wombat Gall, Chris – Dinotrux Harris, Robie H. -

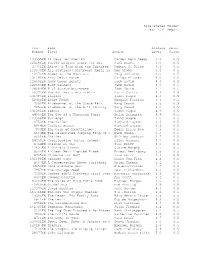

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 133355EN 14 Cows for America Carmen Agra Deedy 4.1 0.5 120186EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Carl Bowen 3.0 0.5 27701EN Akiak: A Tale from the Iditarod Robert J. Blake 3.3 0.5 129370EN All Stations! Distress! April 15 Don Brown 5.4 0.5 12472EN Amber on the Mountain Tony Johnston 3.0 0.5 131685EN Army Delta Force Carlos Alvarez 4.0 0.5 128662EN Army Green Berets Jack David 4.6 0.5 128683EN B-1B Lancers Jack David 4.9 0.5 128684EN B-52 Stratofortresses Jack David 4.7 0.5 20672EN The Bat Boy & His Violin Gavin Curtis 4.1 0.5 131390EN Beagles Tammy Gagne 4.6 0.5 12469EN Beast Feast Douglas Florian 4.4 0.5 7952EN Bluebonnet at the State Fair Mary Casad 3.3 0.5 7953EN Bluebonnet of the Hill Country Mary Casad 4.0 0.5 131391EN Boxers Tammy Gagne 4.9 0.5 44065EN The Boy of a Thousand Faces Brian Selznick 4.8 0.5 123368EN Bulldogs Tammy Gagne 4.5 0.5 8753EN The Caller Richard Laymon 3.3 0.5 8804EN Cardiac Arrest Richard Laymon 3.2 0.5 7904EN The Cask of Amontillado Edgar Allan Poe 7.3 0.5 8604EN The Celebrated Jumping Frog of C Mark Twain 6.9 0.5 8605EN Charles Shirley Jackson 3.7 0.5 54039EN Cheerleading (After School) Ellen Rusconi 5.0 0.5 8754EN Chicken by Che Tana Reiff 3.0 0.5 12697EN A Child's Alaska Claire Murphy 5.7 0.5 8606EN A Clean Well-Lighted Place Ernest Hemingway 3.3 0.5 8705EN Climbing the Wall Tana Reiff 2.9 0.5 131688EN Concept Cars Denny Von Finn 4.1 0.5 8607EN A Conversation About Christmas Dylan Thomas 5.2 0.5 34653EN Cook-a-doodle-doo! Stevens/Crummel 2.7 0.5 7957EN The Courage Seed Jean Richardson 4.6 0.5 7959EN Cowboy Bob's Critters Visit Texa Marjorie vonRosenb 3.5 0.5 8409EN Cowboy Country Ann Scott 4.4 0.5 85025EN The Curse of King Tut's Tomb Michael Burgan 4.5 0.5 12468EN Dandelions Eve Bunting 3.5 0.5 119370EN David Beckham Jeff Savage 4.6 0.5 115738EN The Day the Stones Walked T.A. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value ---------------------------------- -------------------- ------- ------ 12 Again Sue Corbett 4.9 8 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and James Howe 5 9 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Tim Cooke 6.1 1 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10 28 2010: Odyssey Two Arthur C. Clarke 7.8 13 3 NBs of Julian Drew James M. Deem 3.6 5 3001: The Final Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 8.3 9 47 Walter Mosley 5.3 8 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 The A.B.C. Murders Agatha Christie 6.1 9 Abandoned Puppy Emily Costello 4.1 3 Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15 Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6 The Abduction Mette Newth 6 8 Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6 Abhorsen Garth Nix 6.6 16 Abigail Adams: A Revolutionary W Jacqueline Ching 8.1 2 About Face June Rae Wood 4.6 9 Above the Veil Garth Nix 5.3 7 Abraham Lincoln: Friend of the P Clara Ingram Judso 7.3 7 N Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to E.B. Phillips 8 4 N Absolute Brightness James Lecesne 6.5 15 Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7 N The Absolutely True Diary of a P Sherman Alexie 4 6 N An Abundance of Katherines John Green 5.6 10 Acceleration Graham McNamee 4.4 7 An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11 N Accidental Love Gary Soto 4.8 5 Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3 Achingly Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 4.9 4 The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2 Acorna: The Unicorn Girl -

Title Index • 205

The HORN BOOK GUIDE July–December 2007 Title Index • 205 Title Index Abigail Adams, 175 Anansi and the Box of Stories, 123 At Night, 17 Bella Gets Her Skates On, 12 Abortion, 116 Ana’s Story, 171 Atomic Bomb, 181 Ben Franklin, 172 Abortion Controversy, 116 Ancient China, 180 Atoms, 133 Benito Juárez and the French Abracadabra!, 54 Ancient Egypt, 157 Attack of the Evil Elvises, 57 Intervention, 187 Abraham Lincoln, 175 Ancient Egypt, 180 Aunt Nancy and the Bothersome Benjamin Dove, 67 Abraham Lincoln and the Civil Ancient Greece, 180 Visitors, 60 Benjamin Franklin, 171 War, 185 Ancient Maya and Aztec Aurora County All-Stars, 82 Benjamin Franklin, 172 Abraham’s Search for God, 108 Civilizations, 180 Australia, 189 Benjamin Franklin, 175 Absolutely True Diary of a Part- Ancient Mesopotamia, 180 Avatars, 102 Ben’s Bunny Trouble, 47 Time Indian, 84 Ancient Mexico, 157 Avenger, 96 Beowulf, 123 Acids and Bases, 133 Ancient Olympic Games, 164 Aves, 128 Beowulf, 166 Adam Canfield, Watch Your Back!, Ancient Rome, 180 Beowulf, 167 83 And Nobody Got Hurt 2!, 162 Baby, 97 Berenstain Bears and the Big Adaptation, 142 And To Name but Just a Few, 41 Baby Bear, Baby Bear, What Do Spelling Bee, 17 Adolescence, 112 Andersen’s Fairy Tales, 40 You See?, 9 Berenstain Bears Lose a Friend, 17 Adventures of Molly Whuppie and Andruw Jones, 162 Baby Bear’s Big Dreams, 13 Berenstain Bears’ New Kitten, 51 Other Appalachian Folktales, 125 Anfibios, 128 Baby Shower, 19 Bernie Williams, 161 Africa, 184 Angel Isle, 88 Baby / Journey, 73 Best Chef in Second Grade, 52 Africa South of the Sahara, 184 Angela and the Baby Jesus, 35 Babymouse: Puppy Love, 58 Best Eid Ever, 36 Afterlife, 107 Angelina Ice Skates, 29 Babymouse: Skater Girl, 58 Best Hanukkah Ever, 27 Age of Feudalism, 180 Angels among Us, 108 Backbeard, 35 Between the Tides, 139 Agnes Parker. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Tuesday, June 22, 2010 3:47:27PM School: Quincy Jr. High Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 11101 EN 16th Century Mosque, A MacDonald, Fiona MG 7.7 1.0 5,118 NF 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George UG 8.9 17.0 88,942 F 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Verne, Jules MG 10.0 28.0 138,138 F (Unabridged) 34791 EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Clarke, Arthur C. UG 9.0 12.0 64,175 F 111291 EN 2006 NFL Megastars Layden, Joe MG 5.6 1.0 3,285 NF 11592 EN 2095 Scieszka, Jon MG 3.8 1.0 10,043 F 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila MG 3.3 1.0 10,339 F 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue Paola, Tomie De LG 4.4 1.0 6,737 NF 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie MG 4.6 4.0 29,977 F 64569 EN 9.11.01: Terrorists Attack the U.S. Lalley, Patrick MG 7.6 1.0 6,766 NF 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha UG 6.1 9.0 57,139 F 19868 EN Abby's Twin Martin, Ann M. MG 4.2 3.0 23,598 F 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William MG 5.9 3.0 17,610 F 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth UG 6.6 16.0 99,206 F 51005 EN About Insects: A Guide for Children Sill, Cathryn LG 1.7 0.5 101 NF 54089 EN Above the Veil Nix, Garth MG 5.3 7.0 44,306 F 86395 EN Abraham Lincoln Mara, Wil LG 2.5 0.5 280 NF 31812 EN Abraham Lincoln (Famous Schaefer, Lola M. -

Forest Day 2 Programme Book UNFCCC COP 14 Parallel Event Poznan, Poland, 6 December 2008

CO2 Shaping the Global Agenda for Forests and Climate Change Forest Day 2 Programme Book UNFCCC COP 14 Parallel Event Poznan, Poland, 6 December 2008 Forest Day 2 Contents 3 Foreword 5 Acknowledgements 7 Timetable 13 Session 1: Opening Plenary 14 Session 2: Sub Plenary - Cross-Cutting Themes 17 Session 3: Parallel Side Events 37 Session 4: Parallel Side Events 52 Session 5: Closing Plenary 53 Guidelines: Side Events 54 Guidelines: Exhibition Booth 55 Guidelines: Poster Session 56 - Room Allocation 57 - List of Posters 60 List of Exhibition Booth 61 Guidelines: Venue & Floor Map 68 List of Participants Foreword Welcome to Forest Day 2 in Poznan. The first Forest Day at COP 13 in Bali brought together a wide range of stakeholders to participate in debates about forests and climate change. More than 800 participants generated ideas and identified areas of consensus that increased understanding of the issues at stake and helped to move the negotiations forward. With the Bali Road Map in hand, we are now charting our way from Poznan to Copenhagen, a journey that will shape the post-Kyoto climate agreement expected to be concluded at COP 15 in December 2009. The question we face here in Poznan is no longer whether but how forests should be included in a post-2012 climate protection regime. Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD) is squarely on the table as a crucial component 3 of any comprehensive mitigation strategy. And the world is beginning to appreciate the important role of forests in adapting to the changes in climate that are already Forest underway. -

Fabíola Do Socorro Figueiredo Dos Reis Fanfictions Na Internet

Fabíola do Socorro Figueiredo dos Reis Fanfictions na Internet - Um clique na construção do leitor-autor UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARÁ - UFPA Belém – 2011 2 Fabíola do Socorro Figueiredo dos Reis Fanfictions na Internet - Um clique na construção do leitor-autor Dissertação apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da Universidade Federal do Pará, como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre em Estudos Literários. Orientadora: Prof.a Dr.a Lilia Silvestre Chaves Conceito: Excelente UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARÁ - UFPA Belém – 201 3 Fabíola do Socorro Figueiredo dos Reis Fanfictions na Internet - Um clique na construção do leitor-autor Objetivo: Analisar a figura do autor-leitor de fanfictions, alguém que anteriormente foi leitor de uma obra e, depois, passa a escrever a “continuação” ou outras “versões” dela em lugar do autor original. UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARÁ – UFPA Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras Estudos Literários Data de aprovação: 31 de maio de 2011. Banca Examinadora ___________________________________ Prof.a Dr.a Lilia Silvestre Chaves Orientadora - Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA) ___________________________________ Prof. Dr. Júlio César Araújo Membro Externo – Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) ___________________________________ Profª. Drª. Valéria Augusti Membro Interno – Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA) 4 Para Raquel Gonçalves, por todo apoio em vida. Para a Professora Lilia, pela leitura, apoio e grandes ideias. 5 AGRADECIMENTOS À professora orientadora deste projeto, Lilia S. Chaves, pela paciência que teve nas orientações e boa recepção quanto às ideias e mudanças bruscas dos assuntos abordados durante a escrita dos capítulos. Ao apoio da CAPES na manutenção e incentivo à pesquisa na Região Norte do Brasil. -

The Modern Alice Adaptations in Novel, Film and Video Game From

The Modern Alice Adaptations in Novel, Film and Video Game from 2000 - 2012 by Tracey McKenna A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in English – Literary Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2012 © Tracey McKenna 2012 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There have and continue to inspire many adaptations since their publication. The purpose of this thesis is to compare the treatment of the narrative, characters and dialogue of Alice in different forms of media. I will be looking at Frank Beddor’s The Looking Glass Wars, Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland, Nick Willing’s Alice, American McGee’s Alice, and Madness Returns. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor Professor Karen Collins, for her insight and guidance. Without her knowledge and suggestions, this thesis may never have been finished. I would also like to thank Professor Neil Randall and Professor Jennifer Roberts-Smith for reviewing this paper and providing feedback. iv Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Alice’s Audience ...........................................................................................................................................