Health & Climate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High-Resolution Bathymetric Survey of Samoa

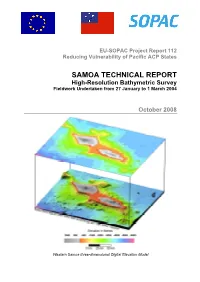

EU-SOPAC Project Report 112 Reducing Vulnerability of Pacific ACP States SAMOA TECHNICAL REPORT High-Resolution Bathymetric Survey Fieldwork Undertaken from 27 January to 1 March 2004 October 2008 Western Samoa three-dimensional Digital Elevation Model Prepared by: Jens Krüger and Salesh Kumar SOPAC Secretariat May 2008 PACIFIC ISLANDS APPLIED GEOSCIENCE COMMISSION c/o SOPAC Secretariat Private Mail Bag GPO, Suva FIJI ISLANDS http://www.sopac.org Phone: +679 338 1377 Fax: +679 337 0040 www.sopac.org [email protected] Important Notice This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Community; however, the views expressed herein must never be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Community. Samoa: High-Resolution Bathymetry EU EDF-SOPAC Reducing Vulnerability of Pacific ACP States – iii TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Geographic Situation .................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Geological Setting ...................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Previous Bathymetry Compilations............................................................................ -

Ethnographic Assessment and Overview National Park of American Samoa

PACIFIC COOPERATIVE STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I AT MĀNOA Dr. David C. Duffy, Unit Leader Department of Botany 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 Technical Report 152 ETHNOGRAPHIC ASSESSMENT AND OVERVIEW NATIONAL PARK OF AMERICAN SAMOA November 2006 Jocelyn Linnekin1, Terry Hunt, Leslie Lang and Timothy McCormick 1 Email: [email protected]. Department of Anthropology, University of Connecticut Beach Hall Room 445, U-2176 354 Mansfield Road Storrs, Connecticut 06269-2176 Ethnographic Assessment and Overview The National Park of American Samoa Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures iii List of Slides v Preface: Study Issues vi Maps vii Key to Maps x I. The Environmental Context 1 Climate and Vegetation 1 The National Park Environments 4 II. Archaeology and Samoan Prehistory 8 Early Settlement 8 Later Inland Settlement 9 Late Prehistoric Period 9 European Contact and the Historical Period 10 Archaeology in the National Park Units 10 III. Research Methodology 15 Documentary Phase 15 Field Research 15 Limitations of the Research 17 IV. Ethnohistory 22 Myths and Legends Relevant to the Park 22 The European Contact Period 25 Western Ethnohistorical and Ethnographic Reports 31 V. Agriculture and Domestically Useful Plants 46 Tutuila Unit 46 Ta'u Unit 49 Ofu Unit 51 Summary 52 VI. Marine Resources 53 Tutuila Unit 53 Ta'u Unit 57 Ofu Unit 58 Summary 61 i VII. Medicinal Plants 63 Ofu Unit 63 Ta'u Unit 66 Tutuila Unit 66 Summary 67 VIII. Analysis of Freelist Data 75 Crops and Cultivated Plants 76 Medicinal Plants 81 Fish and Marine Species 84 Animals and Birds 86 Summary of the Freelist Results 88 IX. -

American Samoa

Date visited: November 8, 2016 American Samoa Previous (American Revolutionary War) (/entry/American_Revolutionary_War) Next (American civil religion) (/entry/American_civil_religion) American Samoa Amerika Sāmoa / Sāmoa Amelika is an unorganized, American Samoa incorporated territory of the United States (/entry/File:American_samoa_coa.png) (/entry/File:Flag_of_American_Samoa.svg) Flag Coat of arms Motto: "Samoa, Muamua Le Atua" (Samoan) "Samoa, Let God Be First" Anthem: The StarSpangled Banner, Amerika Samoa (/entry/File:LocationAmericanSamoa.png) Capital Pago Pago1 (de facto (/entry/De_facto)), Fagatogo (seat of (/entry/List_of_national_capitals) government) Official languages English, Samoan Government President Barack Obama (/entry/Barack_Obama) (D) Governor Togiola Tulafono (D) Lieutenant Governor Ipulasi Aitofele Sunia (D) Unincorporated territory of the United States (/entry/United_States) Tripartite Convention 1899 Deed of Cession of Tutuila 1900 Deed of Cession of Manu'a 1904 Annexation of Swains Island 1925 Area (/entry/List_of_countries_and_outlying_territories_by_area) Date visited: November 8, 2016 199 km² (212th Total (/entry/List_of_countries_and_outlying_territories_by_area)) 76.83 sq mi Water (%) 0 Population 2009 estimate 66,432 2000 census 57,291 326/km² Density 914/sq mi GDP (/entry/Gross_domestic_product) 2007 estimate (PPP) Total $575.3 million Per capita (/entry/Per_capita) Currency (/entry/Currency) US dollar (USD) Internet TLD (/entry/List_of_Internet_top .as level_domains) Calling code ++1684 (/entry/List_of_country_calling_codes) (/entry/United_States), located in the South Pacific Ocean (/entry/Pacific_Ocean) southeast of the sovereign state of Samoa (/entry/Samoa). The native inhabitants of its 70,000 people are descended from seafaring Polynesians (/entry/Polynesia) who populated many islands in the South Pacific. It is a destination spot of many vacationers due to its seasonally sublime climate and miles of clear sandy beaches. -

Mavae and Tofiga

Mavae and Tofiga Spatial Exposition of the Samoan Cosmogony and Architecture Albert L. Refiti A thesis submitted to� The Auckland University of Technology �In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art & Design� Faculty of Design & Creative Technologies 2014 Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... i Attestation of Authorship ...................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ viii Abstract .................................................................................................................................... ix Preface ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Leai ni tusiga ata: There are to be no drawings ............................................................. 1 2. Tautuanaga: Rememberance and service ....................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 6 Spacing .................................................................................................................................. -

'Pacific Destiny' and American Policy in Samoa, 1872-1899

'Pacific Destiny' and American Policy in Samoa, 1872-1899 Stuart Anderson American involvement in Samoa in the late 19th Century constitutes one of the most extraordinary episodes in the diplomatic history of the United States.1 During a period of intense opposition to foreign entanglements and overseas expansion, the United States was embroiled in the affairs of a remote island group where American strategic interests were almost nonexistent and the American economic stake was insigni- ficant. At a time when the expansive policies of William H. Seward and Ulysses S. Grant were handily defeated in the Congress, the Alaska treaty was ridiculed, James G. Blaine's pan-Americanism ended in failure, and Hawaiian annexation remained a task for the future, the United States was ready to enter into agreements regarding Samoa that constituted, in a sense, the nation's first entangling alliance since the French treaty of 1778.2 Yet it is still far from clear what attracted American interest to Samoa. The standard diplomatic history textbooks offer no convincing explanation; all would seem to agree with Thomas A. Bailey that "there was something remarkable about the determination of the United States, ten years before the Spanish-American War, to go to the very brink of hostilities with Germany rather than yield negligible commercial and questionable strategic advantages in faraway Samoa."3 Clearly the United States had no vital interests in the Samoan archipe- lago. Why she was so deeply involved in that part of the world for almost 30 years has remained, therefore, a mystery. It is the contention of this essay that United States involvement in Samoa can be explained only in terms of the idea of America's Pacific destiny that existed in the minds of American policy makers. -

Seawalls in Samoa: a Look at Their Ne Vironmental, Social and Economic Implications Sawyer Lawson SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2011 Seawalls in Samoa: A Look at Their nE vironmental, Social and Economic Implications Sawyer Lawson SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Environmental Health and Protection Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Place and Environment Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Lawson, Sawyer, "Seawalls in Samoa: A Look at Their nE vironmental, Social and Economic Implications" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1058. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1058 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seawalls in Samoa: A Look at Their Environmental, Social and Economic Implications Sawyer Lawson Project Advisor: Espen Ronneberg Academic Director: Jackie Fa’asisila S.I.T. Samoa, Spring 2011 Abstract: This study concerns the environmental, economic and social implications of seawalls in Samoa. Information for this study was gathered using a combination of secondary sources and primary sources including interviews, surveys and participant observation. Given the cultural and economic importance of Samoa’s coastline and the fact that seawalls, which already occupy much of Samoa’s coast, are becoming more abundant, it is important to understand the implications of building them. The researcher found that partially due to climate change and sand mining, Samoa’s coastline has become increasingly threatened by erosion and coastal retreat. -

WORLD CATALOGUE of THESES on the PACIFIC ISLANDS Dickson Familiarity with Theses and Dissertations on His Subject Is Essential to the Research Worker

WORLD CATALOGUE OF THESES ON THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Dickson WORLD CATALOGUE OF THESES ON THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Diane Dickson and Carol Dossor Familiarity with theses and dissertations on his subject is essential to the research worker. These usually unpublished works are not, however, normally included in bibliographies and manuscript catalogues. As early as 1955 the growing number of theses on the Pacific islands had led to a demand for a catalogue, which was partially met by the publication of an Index o f Social Science Theses on the South Pacific. The growing recognition of the importance of the Pacific area now calls for a more comprehensive inventory, covering all disciplines, which this cata logue attempts to supply. The catalogue is based on the micro film Library of Theses on the Pacific Islands maintained by the Department of Pacific History of the Australian National University, and expanded by study of all available theses catalogues and by requests for information from universities known to be interested in Pacific studies. It contains more than 1,000 entries and will be an essential aid to all workers in the field of Pacific studies. Price in Australia $3.90 This book was published by ANU Press between 1965–1991. This republication is part of the digitisation project being carried out by Scholarly Information Services/Library and ANU Press. This project aims to make past scholarly works published by The Australian National University available to a global audience under its open-access policy. WORLD CATALOGUE OF THESES ON THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Pacific Monographs This series, under the general editorship of H. -

156 Annotated Bibliography American Samoa. 1978. Census Of

Annotated Bibliography American Samoa. 1978. Census of Agriculture. 1981 part 55: American Samoa. U.S. Department of Commerce. With data organized by county, the census gives amount of land under cultivation, amount and type of crops grown, amount and type of animals raised, and age data on farmers. Amerson, A., W. Whistler, and T. Schwaner. 1982. Wildlife and Wildlife Habitat of American Samoa I. Environment and Ecology. Washington DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. This is a general survey of the natural environment. Amerson, A., W. Whistler, and T. Schwaner. 1982. Wildlife and Wildlife Habitat of American Samoa II. Accounts of Flora and Fauna. Washington DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. This is a biological survey of the fauna and floral components of the natural environment of American Samoa. Ashmole, M. J. 1963. Guide to the Birds of Samoa. Honolulu: Bishop Museum. The author gives descriptions, distribution, scientific identifications, and Samoan names. Data are mostly from published sources and the Bishop Museum specimen collection. Bougainville, Louis de. 1967 [1772]. A Voyage Round the World Performed by Order of His Most Christian Majesty, in the Years 1766, 1767, 1768, and 1769. John Reinhold Forster, trans. London. Reprint ed., New York: Da Capo Press. Bougainville dubbed the Samoan islands 'the Navigators.' He visited the islands on May 3, 1768, and made a few exchanges with people of Ofu and Olosega; see pages 278-83. Bryan, E.H. 1935. Samoan and scientific names of plants found in Samoa. Mimeo. Honolulu: Bernice P. Bishop Museum. -

Inventory and Monitoring of Seabirds in National Park of American Samoa

Final Report. Technical Report 136 INVENTORY AND MONITORING OF SEABIRDS IN NATIONAL PARK OF AMERICAN SAMOA By Paul J. O’Connor and Mark J. Rauzon October 2004 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I AT MANOA NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CONTRACT NO. 8036-2-9004 CONTRIBUTION NUMBER 136 PSCU/UH - i - Item Page Table of Contents i List of Figures iii List of Tables iv Report Summary 1 Project Introduction 3 Background 3 Study Area 4 Study Species 11 Methods 13 General Methods 13 Complete Island Surveys 15 Fixed Location Counts 17 High-Elevation Ground & 19 Cliff Nesters Results & Discussion 22 General Results & Discussion 22 Complete Island Surveys 22 Fixed location Counts 35 Seabird Colonies 38 Coastal Breeders 38 High-Elevation Ground & Cliff 40 Nesters Species Present 40 Nests 43 Petrel Distributions Elsewhere 44 in American Samoa Petrel Specimens & Natural 45 History Rose Atoll Seabirds 49 Conclusions 50 Monitoring & Its Future at 50 NPSA Seabird Population Status 52 Field Access & Operations 54 Developing Additional 55 Survey Methods Invasive Species 56 - ii - Invertebrates 56 Vertebrates 56 Rodent Control 60 Human Impacts 63 Recommendations 64 Tutuila Unit 64 Manu’a Units 65 Acknowledgments 66 References 67 Appendices 71-140 Appendix A: Seabird Accounts for American Samoa 71 Appendix B: Tutuila and Aunu’u Islands, Round Island 98 Survey Site Maps Appendix C: Tahiti Petrel Voice Analysis 112 Appendix D: Ectoparasites from Tahiti Petrel on Ta’u 116 Appendix E: Radar Survey Techniques Employed at 119 Channel Islands National Park Appendix F: Establishing a Water Collection System 123 and Base Camp on Mt. Lata Appendix G: Status of the Spotless Crake in American 124 Samoa Appendix H: Coastal Seabird Colonies Maps for 130 American Samoa Appendix I: Brief Video Clips from Summit of Mt. -

PACIFIC ISLANDS (Fiji, Samoa, Tonga)

PACIFIC ISLANDS (Fiji, Samoa, Tonga) Who is a Pacific Islander? The “Pacific Islands” is how we are described because of our geographic location, “Islands, geographically located in the Pacific Ocean”. Today, we will talk and share with educators, health experts, and community members of the three dominant Pacific Islander populations who live in San Mateo County, namely, Fijians, Samoans, and Tongans. PACIFIC ISLAND NATIONS • When you talk about the Pacific Islands, you are talking about different Island Nations. • Different heads of countries, from kings to presidents, etc. Even different forms of government. • Some are independent countries, yet some are under the rule of a foreign power. PACIFIC ISLAND NATIONS • Each Island Nation has their own language. • There is not one language that is used or understood by all Pacific Islanders. • There are some similarities but each island nation has it’s own unique characteristics. • Challenge in grouping the islands as just one group, “Pacific Islanders”. ISLANDS OF THE PACIFIC GREETINGS • From the Islands of Fiji “Bula Vinaka” • From the Islands of Samoa “Talofa Lava” • From the Kingdom of Tonga “Malo e Lelei” • From Chamorro “Hafa Adai” • From Tahiti “Ia Orana” • From Niue “Fakalofa atu” • From NZ Maoris “Tena Koe” • From Hawaii “Aloha” FIJI ISLANDS • Group of volcanic islands in the South Pacific, southwest of Honolulu. • Total of 322 islands, just over 100 are inhabited. • Biggest island Viti Levu, is the size of the “Big Island” of Hawaii. • Larger islands contain mountains as high as 4,000 feet. PEOPLE OF FIJI • Indigenous people are Fijians who are a mixture of Polynesian and Melanesian. -

The US Federal Framework and American Samoa

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON BOTHELL Constitutional Ambiguity as Policy: The U.S. Federal Framework and American Samoa Kerry L Francis 6/9/2014 A Capstone project presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Policy Studies, School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences, UWB. Acknowledgements I would like to extend my heartfelt appreciation to Professor Camille Walsh for her helpful guidance and indispensable insight in the writing of this paper; and to Professor Johanna Crane, whose comments greatly factored in the paper’s final outcome. Also, I must acknowledge Professors Alan Wood, Bruce Kochis, Daniel Goldhaber, Daniel Jacoby, Keith Nitta, Nives Dolšak, and Shauna Carlisle, whose instruction imparted in me in each their own way, something beyond the learning of the course and program curriculum in the classroom. And finally—to Jennifer—whose steady encouragement, counsel and friendship since those sunny years in high school, bumped and pushed me along to this moment. i For Noah. ii Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I – the Policy Problem…………………………………………………………………….2 Chapter II – Literature Review……………………………………………………………….........9 Chapter III – Methodology……………………………………………………………………….21 Discussion of Methods…………………………………………………………………...23 Chapter IV – Results and Discussion..............................................................................................26 South Pacific Preludes……………………………………………………………………31 The Deeds of Cession and the Early Phase of -

Social Policies in Samoa

Social Policies in Samoa Desmond U. Amosa ß Commonwealth Secretariat and United Nations Research Institute for Social Development 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher. Published by the Commonwealth Secretariat Edited by Wayzgoose Designed by The Charlesworth Group Cover design by Tattersall Hammarling & Silk Printed by Hobbs the Printers, Totton, Hampshire Established in 1963, the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) is an autonomous institution within the UN system that carries out multidisciplinary research on the social dimensions of contemporary development issues. Through its research, UNRISD stimulates dialogue and contributes to policy debates on key issues of social development within and outside the UN system. Visit www.unrisd.org for full details. The Commonwealth is a voluntary association of 54 countries that support each other and work together towards shared goals in democracy and development. The Commonwealth Secretariat executes plans agreed by Commonwealth Heads of Government through technical assistance, advice and policy development. It works as a trusted partner for all Commonwealth people as: a force for peace, democracy, equality and good governance; a catalyst for global consensus-building; and a source of assistance for sustainable development and poverty eradication. Views and opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors and should in no way be attributed to the institutions to which they are affiliated or to the Commonwealth Secretariat or UNRISD.