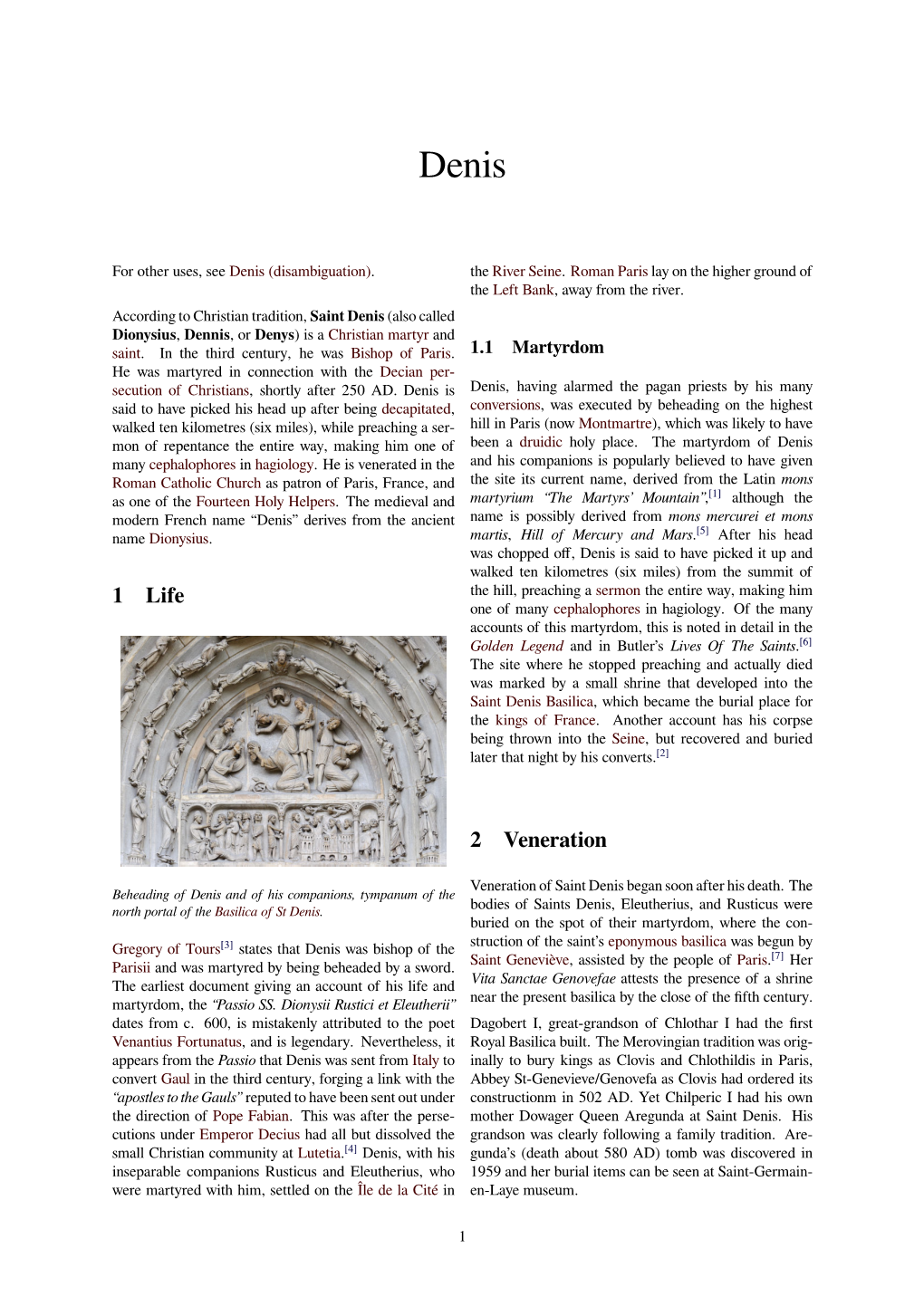

1 Life 2 Veneration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Letter to Pope Francis Concerning His Past, the Abysmal State of Papism, and a Plea to Return to Holy Orthodoxy

A Letter to Pope Francis Concerning His Past, the Abysmal State of Papism, and a Plea to Return to Holy Orthodoxy The lengthy letter that follows was written by His Eminence, the Metropolitan of Piraeus, Seraphim, and His Eminence, the Metropolitan of Dryinoupolis, Andrew, both of the Church of Greece. It was sent to Pope Francis on April 10, 2014. The Orthodox Christian Information Center (OrthodoxInfo.com) assisted in editing the English translation. It was posted on OrthodoxInfo.com on Great and Holy Monday, April 14, 2014. The above title was added for the English version and did not appear in the Greek text. Metropolitan Seraphim is well known and loved in Greece for his defense of Orthodoxy, his strong stance against ecumenism, and for the philanthropic work carried out in his Metropolis (http://www.imp.gr/). His Metropolis is also well known for Greece’s first and best ecclesiastical radio station: http://www.pe912fm.com/. This radio station is one of the most important tools for Orthodox outreach in Greece. Metropolitan Seraphim was born in 1956 in Athens. He studied law and theology, receiving his master’s degree and his license to practice law. In 1980 he was tonsured a monk and ordained to the holy diaconate and the priesthood by His Beatitude Seraphim of blessed memory, Archbishop of Athens and All Greece. He served as the rector of various churches and as the head ecclesiastical judge for the Archdiocese of Athens (1983) and as the Secretary of the Synodal Court of the Church of Greece (1985-2000). In December of 2000 the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarch elected him as an auxiliary bishop of the Holy Archdiocese of Australia in which he served until 2002. -

Contents Inhalt

34 Rome, Pantheon, c. 120 A.D. Contents 34 Rome, Temple of Minerva Medica, c. 300 A.D. 35 Rome, Calidarium, Thermae of Caracalla, 211-217 A.D. Inhalt 35 Trier (Germany), Porta Nigra, c. 300 A.D. 36 NTmes (France), Pont du Gard, c. 15 B.C. 37 Rome, Arch of Constantine, 315 A.D. (Plan and elevation 1:800, Elevation 1:200) 38-47 Early Christian Basilicas and Baptisteries Frühchristliche Basiliken und Baptisterien 8- 9 Introduction by Ogden Hannaford 40 Rome, Basilica of Constantine, 310-13 41 Rome, San Pietro (Old Cathedral), 324 42 Ravenna, Sant' Apollinare Nuovo, c. 430-526 10-19 Great Buildings of Egypt, Mesopotamia and Persia 42 Ravenna, Sant'Apollinare in Classe, 534-549 Grosse Bauten Ägyptens, Mesopotamiens und Persiens 43 Rome, Sant' Agnese Fuori Le Mura, 7th cent. 43 Rome, San Clemente, 1084-1108 12 Giza (Egypt), Site Plan (Scale 1:5000) 44 Rome, Santa Costanza, c. 350 13 Giza, Pyramid of Cheops, c. 2550 B.C. (1:800) 44 Rome, Baptistery of Constantine (Lateran), 430-440 14 Karnak (Egypt), Site Plan, 1550-942 B.C. (1:5000) 44 Nocera (Italy), Baptistery, 450 15 Abu-Simbel (Egypt), Great Temple of Ramesses II, c. 1250 B.C. 45 Ravenna, Orthodox Baptistery, c. 450 (1:800, 1:200) 15 Mycenae (Greece), Treasury of Atreus, c. 1350 B.C. 16 Medinet Habu (Egypt), Funerary Temple of Ramesses II, c. 1175 B.C. 17 Edfu (Egypt), Great Temple of Horus, 237-57 B.C. 46-53 Byzantine Central and Cross-domed Churches 18 Khorsabad (Iraq), Palace of Sargon, 721 B.C. -

The Column Figures on the West Portal of Rochester Cathedral

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society A QUESTION OF IDENTITY? THE COLUMN FIGURES ON THE WEST PORTAL OF ROCHESTER CATHEDRAL S. BLISS In the summer of 1991, the Romanesque west front of Rochester Cathedral (Plate I) underwent thorough cleaning and conservation.' This event draws attention, once again, to the significance of the façade and its sculptural enrichment within the development of English Romanesque art. The west portal (Plate II) is an important monument of this period and occupies a place of special significance in understanding some of the links between the theological, cultural and artistic concerns of the day. It would appear that both the patrons and sculptors of the west portal were highly aware of contemporary Continental precedents and this is made clear by an examination of the column figures incorporated into the jambs (Plates III and IV). They instigated work, which in its theological and aesthetic programme, was unusually rare in England and, perhaps more importantly, saw fit to adapt their subject-matter to express a number of concerns both spiritual and temporal. The figures' identities have been the subject of some debate and, though contemporary scholarship identifies them as King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, it is the intention of this short paper to review their formal uniqueness within the English Romanesque, the debates surrounding their attribution and to provide a possible reading of their meaning within the context of the Rochester portal. Before describing and discussing the figures in detail, it will be useful to consider their physical context within the design of the cathedral's west front. -

Notre-Dame of Paris and the Anticipation of Gothic 231

Notre-Dame of Paris and the Anticipationof Gothic StephenMurray In his Entretiens sur l'architectureEugene-Emmanuel Viollet-le- ment with the archaeological data underlying Viollet-le-Duc's Duc presented four schematic plans that, seen in sequence, understanding of Notre-Dame of Paris in the history of project a dynamic theory of medieval architecture (Fig. 1).1 architecture or from any systematic review of the enormously In the first plan two parallel lines of small circles run inside rich historiographical documentation, has dismissed such two continuous bands; one is invited to think of the slender teleological conceits, compromised, as they are, by the taint of columns and thin outer walls of a wooden-roofed Roman or modernism. We are told in the most recent monograph that Early Christian basilica. In the second (hypothetical) basilica Notre-Dame was, in fact, conceived and built entirely without the weight and thrust of masonry vaults has necessitated flying buttresses; that flyers are not even necessary for the thickened walls and supports. In the third, the vaults are structural integrity of such an edifice.7 Flying buttresses, it is supported by compound piers and thick exterior walls rein- alleged, were added only in the thirteenth and fourteenth forced with buttresses.2 In relation to these three paper centuries-principally as a means to evacuate the rainwater "edifices," expressing the first millennium of ecclesiastical from the high roof along the gutters set in their crests. The architecture, the fourth is seen to be radically different. It is as massive outer uprights of the cathedral, it is claimed, result if the exterior wall had been broken into segments and each from a later intervention. -

The Early Church Fathers on Peter's Presence in Rome

The Early Church Fathers on Peter's Presence in Rome Some contend that Peter couldn’t have been the bishop of Rome because he was never in Rome. This of course runs counter to the testimony of the Early Fathers and Scripture. In 1 Peter 5:12-13 Peter says: “I write you this briefly through Silvanus, whom I consider a faithful brother, exhorting you and testifying that this is the true grace of God. Remain firm in it. The chosen one at Babylon sends you greeting, as does Mark, my son.” Babylon is a code word for Rome and is used elsewhere in Scripture to mean the same thing. Examples can be found in Revelation 18:2, 18:10 and 18:21. Further evidence can be found in Rome itself as Peter’s tomb is located under ST Peter’s Basilica. Dionysius of Corinth You have also, by your very admonition, brought together the planting that was made by Peter and Paul at Rome and at Corinth; for both of them alike planted in our Corinth and taught us; and both alike, teaching similarly in Italy, suffered martyrdom at the same time (Letter to Soter of Rome [inter A.D. 166 -174] as recorded by Eusebius). Irenaeus Matthew also issued among the Hebrews a written Gospel in their own language, while Peter and Paul were evangelizing in Rome and laying the foundation of the Church. (Against Heresies 3:1:1 [A.D. 189]). Caius It is recorded that Paul was beheaded in Rome itself, and Peter, likewise, was crucified, during the reign [of the Emperor Nero]. -

The Anti-Heretical Activities of the Roman Church in the Second Century

HISTOREIN VOLUME 6 (2006) The church of Rome was actively involved Christians against in the disputes and conflicts that challenged the Christian movement throughout the Christians: Roman Empire from a very early period. Its interference in the affairs of other com- The Anti-heretical munities is most evident in the anti-hereti- cal campaigns launched by its leaders as well as in the efforts those leaders made to Activities of the found a universal church. This article shall restrict itself to the second century and as Roman Church much as possible to the middle of that cen- tury. This period has not been investigated in the Second much due to the lack of reliable evidence. But as it seems to have been crucial for later developments, it is worth some close Century scrutiny. Most of what I will present in this article is not highly original – and what is original is not always very solid. My debt to previous studies will be clear enough and my own conjectures underlined. But I hope that a fresh examination of the scant evidence may stimulate discussion that could lead to a slightly new evaluation of the situation. Dimitris J. Kyrtatas I shall argue that the leaders of the Chris- University of Thessaly tian community of Rome started develop- ing, from a very early stage, an ambitious plan that they consciously pursued in a most persistent manner. To facilitate dis- cussion, my arguments are grouped under four headings. I deal firstly with examples of what may be called clear cases of direct intervention; secondly, with the means em- ployed and the weapons used in such inter- ventions; thirdly, with the reasons behind Rome’s intervention; and fourthly, with the strategy and the aims of the intervention as well as with an estimate of the results, suc- cesses and failures of the endeavour. -

The Roman Primacy in the Second Century and the Problem of the Development of Dogma James F

THE ROMAN PRIMACY IN THE SECOND CENTURY AND THE PROBLEM OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF DOGMA JAMES F. McCUE Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pa. HPHE DOCTRINE which distinguishes Roman Catholicism from all * other Christian communities is the primacy of the bishop of Rome. The prevailing Roman Catholic interpretation of the New Testament and the early Christian record is that Jesus commissioned Peter to be the ultimate foundation and source of unity for the apos tolic Church. Peter, as he neared the end of his career, determined that the bishop of the Roman community was to be his successor. Hence forth each successive bishop of the Roman See is to the Church of his age what Peter was to the Church of the age of the apostles. In consequence of this general view of how things must have tran spired in the first and second centuries it is supposed that each suc cessive Roman bishop was aware of his special primatial authority and that his contemporaries—at least those who were properly informed —recognized this primacy. The paucity of evidence for the Roman primacy during the hundred years or so after the apostles is explained by the fact that there was really little occasion for its exercise. How ever, it is maintained that there is some evidence and that its quantity is about what one would expect given the situation of the Church at the time. What development takes place is thus a development in the exercise of the primacy. As certain problems became more and more pressing, the primacy became more important in the life of the Church; but the primacy was always "there," claimed and recognized, just waiting to come into greater prominence. -

Lent | Holy Week | Easter #Lentpilgrim INTRODUCTION

lent | holy week | easter #LentPilgrim INTRODUCTION his Lent, the Church of England is focusing on pilgrimage. In that spirit, we have created this virtual pilgrimage which T takes us on a journey from the Cathedral to the Cross, from Bristol to the bitter passion of Golgotha. It is not a straight path, as life is not straightforward, but twists and turns through the countries, and across the centuries. Accompanied by saints with links to places along the way, we will journey through Lent as we travel across Britain, France, Italy, and on into the Middle East. As we reach Rome, the pilgrimage retraces the journey of St Paul, in reverse, taking us from Rome, through Sicily, Malta, Rhodes, and beyond, until we arrive in Jerusalem, at the foot of the Cross. In addition to this devotional pilgrimage, from the back page of this booklet you will find details of services on Easter Day and in Holy Week, along with additional events and services such as the Lent Lunches, reading Mark right through, and Stations of the Cross. We pray that you will choose to travel with us for part or all of this journey. Booklet compiled and created by Tim Popple, 2019 FORTY DAYS AND FORTY NIGHTS Day 1 Jordan Bristol Day 2 Aldhelm Malmesbury Day 3 Osmund Salisbury Day 4 Swithun Winchester Day 5 Frideswide Oxford Day 6 Alban St Albans Day 7 John Donne London Day 8 William Rochester Day 9 Æthelberht Kent Day 10 Thomas Becket Canterbury Day 11 Richard of Chichester Dover Day 12 William de St-Calais Calais Day 13 Remigius Picardy Day 14 Joan of Arc Rouen Day 15 Thérèse -

The Rise of the Monarchical Episcopate

THE RISE OF THE MONARCHICAL EPISCOPATE KENNETH A. STRAND Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan It is generally recognized that by the time of Irenaeus (ca. A.D. 185) the monarchical episcopate with its threefold ministry of bishop ( &zimoxo<) elders (xpeapb~spot) and deacons ( 8~&xovot) had well-nigh universally replaced what is often considered an earlier organizational pattern of a twofold ministry of bishops or elders (that is, bishops-elders) and deacons. The question of how and when the monarchical episcopate developed has occasioned much discussion, some of which has been based more on modern theological concepts than on a careful consideration of the ancient historical sources. Though in some quarters the matter appears still to be a rather live issue, discussion seems for the most part The earliest evidence for the latter pattern is to be found in some NT references we shall notice shortly. Here a word about terminology is in order: In harmony with standard practice, "monarchical epis- copate, " "monepiscopacy, " and "threefold ministry" will be used synonymously for that type of church organization where on a local level one individual, usually designated the bishop, is in charge of the church (assisted by elders and deacons) ; and "presbyterial orga- nization," "twofold ministry," etc., will be used synonymously to refer to the type of local organization where a board of elders (or bishop-elders) has charge (assisted by deacons). The method of appointment or election is not a consideration in this usage, but the fact of such appointment or election for service on a local 2evel is. It is recognized, of course, that our sources at times use the term "elders" to mean "older men," as well as in this more restricted way. -

Burgundian Gothic Architecture

BURGUNDIAN GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE ROBERT BRANNER DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, NEW YORK A. ZWEMMER LTD LONDON tjj V1 © 1960 A. ZWEMMER LTD, 76-80 CHARING CROSS ROAD, LONDON WC2 MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BLOCKS ETCHED BY W. F. SEDGWICK LTD, LONDON SEI TEXT AND ILL USTRATIONS PRINTED BY PERCY LUND, HUMPHRIES AND CO. LTD, BRADFORD BOUND BY KEY AND WHITING LTD, LONDON NI Contents List of Plates I. Auxerre Cathedral, the interior of the chevet 2a. Anzy Ie Due, the nave 2b. Paray Ie Monial, the nave 3a. Fontenay, the nave 3b. Pontigny, the nave 4a. Fontenay, the chapter house 4b. Vermenton, detail of the nave sa. Bar sur Aube, St Pierre, the exterior of the chevet sb. Bar sur Aube, St Maclou, detail of the nave 6a. Chablis, St Pierre, the nave 6b. Montreal, the crossing and apse 7a. Langres Cathedral, the interior 7b. Bar sur Aube, St Maclou, the nave Sa. Sens Cathedral, the interior of the chevet sb. Chablis, St Martin, the hemicycle 9a. Auxerre, St Eusebe, the nave 9b. Vezelay, the interior of the chevet 10. Pontigny, the interior of the chevet lIa. Canterbury, a detail of Trinity Chapel IIb. Geneva, former Cathedral, a detail of the choir 12a. Troyes, Madeleine, a detail of the choir I2b. Sens Cathedral, a detail of the north tower wall 13a. Auxerre Cathedral, the north aisle of the chevet 13b. Clamecy, St Martin, the ambulatory wall 14. Auxerre Cathedral, an exterior detail of the hemicycle clerestory IS. Auxerre Cathedral, a detail of the clerestory and triforium 16a. -

CONTEXTS of the CADAVER TOMB IN. FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLAND a Volumes (T) Volume Ltext

CONTEXTS OF THE CADAVER TOMB IN. FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLAND a Volumes (T) Volume LText. PAMELA MARGARET KING D. Phil. UNIVERSITY OF YORK CENTRE FOR MEDIEVAL STUDIES October, 1987. TABLE QE CONTENTS Volume I Abstract 1 List of Abbreviations 2 Introduction 3 I The Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth Century England: The Problem Stated. 7 II The Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth Century England: The Surviving Evidence. 57 III The Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth Century England: Theological and Literary Background. 152 IV The Cadaver Tomb in England to 1460: The Clergy and the Laity. 198 V The Cadaver Tomb in England 1460-1480: The Clergy and the Laity. 301 VI The Cadaver Tomb in England 1480-1500: The Clergy and the Laity. 372 VII The Cadaver Tomb in Late Medieval England: Problems of Interpretation. 427 Conclusion 484 Appendix 1: Cadaver Tombs Elsewhere in the British Isles. 488 Appendix 2: The Identity of the Cadaver Tomb in York Minster. 494 Bibliography: i. Primary Sources: Unpublished 499 ii. Primary Sources: Published 501 iii. Secondary Sources. 506 Volume II Illustrations. TABU QE ILLUSTRATIONS Plates 2, 3, 6 and 23d are the reproduced by permission of the National Monuments Record; Plates 28a and b and Plate 50, by permission of the British Library; Plates 51, 52, 53, a and b, by permission of Trinity College, Cambridge. Plate 54 is taken from a copy of an engraving in the possession of the office of the Clerk of Works at Salisbury Cathedral. I am grateful to Kate Harris for Plates 19 and 45, to Peter Fairweather for Plate 36a, to Judith Prendergast for Plate 46, to David O'Connor for Plate 49, and to the late John Denmead for Plate 37b. -

The Stained Glass of John Hardman and Company Under the Leadership of John Hardman Powell from 1867 to 1895

The Stained Glass of John Hardman and Company under the leadership of John Hardman Powell from 1867 to 1895 Mathé Shepheard Volume I Text Based on a thesis presented at Birmingham City University in January 2007 Copyright © 2010 Mathé Shepheard This text is Volume I of The Stained Glass of John Hardman and Company under the leadership of John Hardman Powell from 1867 to 1895 by Mathé Shepheard. The accompanying two volumes of Plates can be downloaded from the same site. CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements 11 Preface 12 Note on viewing 14 Chapter One The Historical and Religious Background 15 Chapter Two The Crucifixion 32 Chapter Three Typology 49 Chapter Four Events in the life of the Lord 58 Chapter Five Saints 72 Chapter Six The Virgin Mary 92 Chapter Seven Conclusion 103 Appendix One Saints 112 Appendix Two Note on Kempe 115 Appendix Three Further considerations on viewing 117 Tables: Table 1. Analysis of 106 Crucifixion windows by content and decade 120 Table 2. Lady Patrons’ windows 1865-76 121 Table 3. Production of Windows in selected years with cost ranges 122 Table 4. Number of Schemes by Architect 1865 to 1890 123 Archive Abbreviations 124 Bibliography 124 Previous Publication 132 3 List of Plates Volume II – Plates 1 to 54 Plates 1 to 26–Illustrations for Chapter 2, The Crucifixion. Plate Number 1. East Window, St. Bartholomew and All Saints, Wootton Bassett, 1870. 2. East Window, Lady Chapel, Hereford Cathedral, 1874. 3. East Window, The Immaculate Conception and St. Dominic, Stone, 1866. 4. East Window, St. John the Baptist, Halesowen, Window and Sketch, 1875.