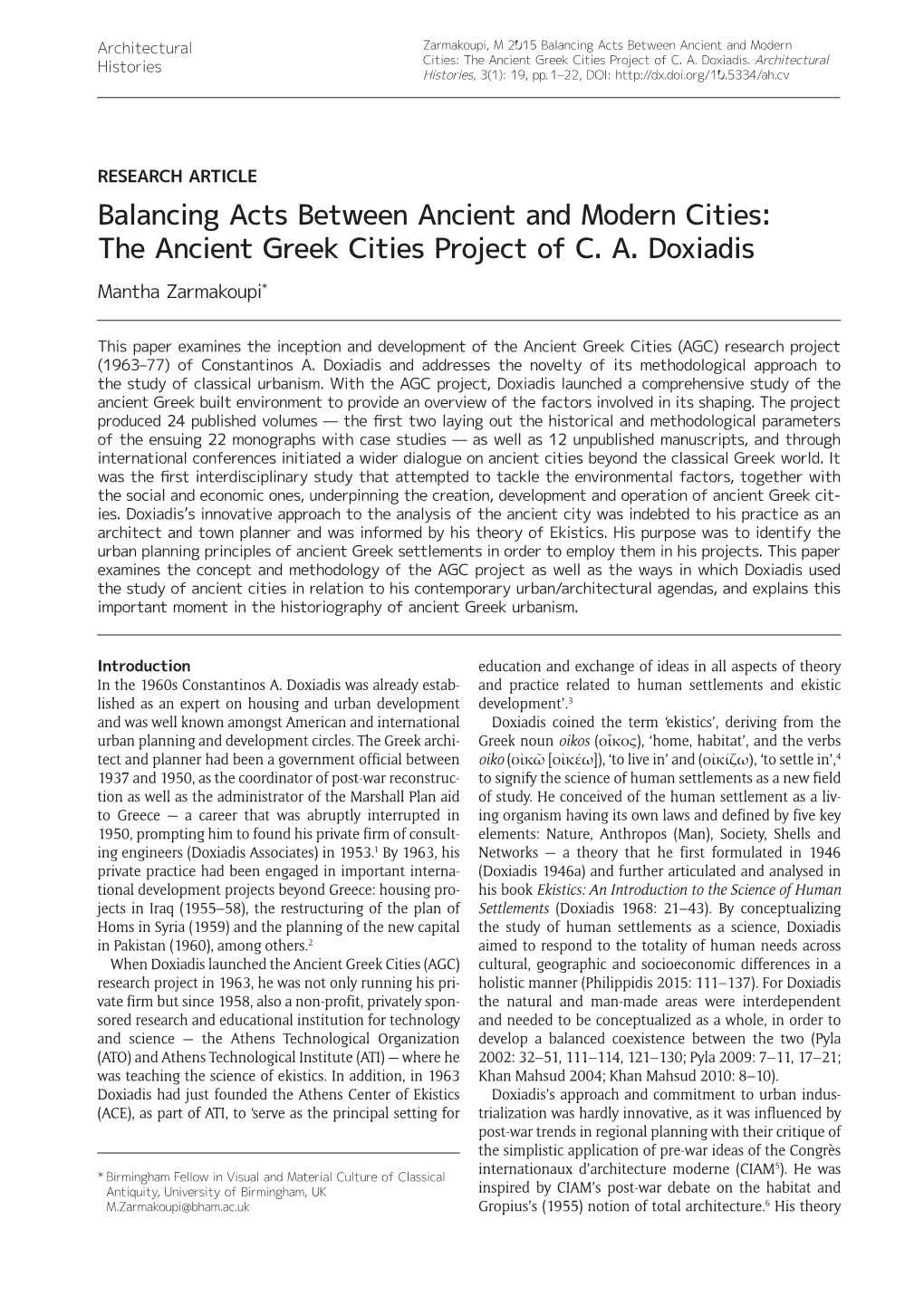

The Ancient Greek Cities Project of CA Doxiadis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

Urbanistica N. 146 April-June 2011

Urbanistica n. 146 April-June 2011 Distribution by www.planum.net Index and english translation of the articles Paolo Avarello The plan is dead, long live the plan edited by Gianfranco Gorelli Urban regeneration: fundamental strategy of the new structural Plan of Prato Paolo Maria Vannucchi The ‘factory town’: a problematic reality Michela Brachi, Pamela Bracciotti, Massimo Fabbri The project (pre)view Riccardo Pecorario The path from structure Plan to urban design edited by Carla Ferrari A structural plan for a ‘City of the wine’: the Ps of the Municipality of Bomporto Projects and implementation Raffaella Radoccia Co-planning Pto in the Val Pescara Mariangela Virno Temporal policies in the Abruzzo Region Stefano Stabilini, Roberto Zedda Chronographic analysis of the Urban systems. The case of Pescara edited by Simone Ombuen The geographical digital information in the planning ‘knowledge frameworks’ Simone Ombuen The european implementation of the Inspire directive and the Plan4all project Flavio Camerata, Simone Ombuen, Interoperability and spatial planners: a proposal for a land use Franco Vico ‘data model’ Flavio Camerata, Simone Ombuen What is a land use data model? Giuseppe De Marco Interoperability and metadata catalogues Stefano Magaudda Relationships among regional planning laws, ‘knowledge fra- meworks’ and Territorial information systems in Italy Gaia Caramellino Towards a national Plan. Shaping cuban planning during the fifties Profiles and practices Rosario Pavia Waterfrontstory Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Monica Bocci Brasilia, the city of the future is 50 years old. The urban design and the challenges of the Brazilian national capital Michele Talia To research of one impossible balance Antonella Radicchi On the sonic image of the city Marco Barbieri Urban grapes. -

Evaluation of the Human Settlements Environment of Public Housing Community: a Case Study of Guangzhou

sustainability Article Evaluation of the Human Settlements Environment of Public Housing Community: A Case Study of Guangzhou Fan Wu 1, Yue Liu 2, Yingyan Zeng 1, Hui Yan 1, Yi Zhang 3 and Ling-Hin Li 4,* 1 Department of Construction Management, School of Civil Engineering and Transportation, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510641, China; [email protected] (F.W.); [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (H.Y.) 2 School of Architecture, Building and Civil Engineering, Loughborough University, Leicestershire LE11 3TU, UK; [email protected] 3 Guangzhou Municipal Housing and Urban-Rural Development Bureau, Guangzhou 510030, China; [email protected] 4 Department of Real Estate and Construction, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +85-23-917-8932 Received: 20 July 2020; Accepted: 2 September 2020; Published: 8 September 2020 Abstract: With the improvement of social housing policies and an increase in the quantity of public housing stock, issues such as poor property management service, poor housing quality, and insufficient public services remain to be resolved. This study focuses on the human settlement environments of public housing communities in Guangzhou and establishes an evaluation system containing built environments and housing environments satisfaction criteria. In our analysis, the evaluation system was modified using data collected from surveys through factor analysis, which reduced dimensions to the indoor environment, the community environment, and social relations. Moreover, multivariable regression analysis was performed to identify the differences of needs among residents with different living environments and family backgrounds. The result shows that housing area, transportation resources, and public services have met the basic needs of residents who were generally satisfied with the community environment of their public housing. -

10 Megaregions Reconsidered: Urban Futures and the Future of the Urban

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository 1 10 Megaregions reconsidered: urban futures and the future of the urban John Harrison and Michael Hoyler 10.1 An introduction to (more than just) a debate on megaregions We live in a world of competing urban, regional and other spatial imaginaries. This book’s chief concern has been with one such spatial imaginary – the megaregion. More particularly, its theme has been the assertion that the megaregion constitutes globalization’s new urban form. Yet, what is clear is that the intellectual and practical literatures underpinning the megaregion thesis are not internally coherent and this is the cause of considerable confusion over the precise role of megaregions in globalization. This book has offered one solution through its focus on the who, how and why of megaregions much more than the what and where of megaregions. In short, moving the debate forward from questions of definition, identification and delimitation to questions of agency (who or what is constructing megaregions), process (how are megaregions being constructed), and specific interests (why are megaregions being constructed) is the contribution of this book. The individual chapters have interrogated many of the claims and counter-claims made about megaregions through examples as diverse as California, the US Great Lakes, Texas and the Gulf Coast, Greater Paris, Northern England, Northern Europe, and China’s Pearl River Delta. But, as with any such volume, our approach has offered up as many new questions as it has provided answers. -

Doxiadis, from Ekistics to the Delos Meetings

17th IPHS Conference, Delft 2016 | HISTORY URBANISM RESILIENCE | VOLUME 06 Scales and Systems | Policy Making Systems of City,Culture and Society- | Urbanism and- Politics in the 1960s: Permanence, Rupture and Tensions in Brazilian Urbanism and Development URBAN pLANNING IN GUANABARA STATE, BRAZIL: DOXIADIS, FROM EKISTICS TO THE DELOS MEETINGS Vera Rezende Universidade Federal Fluminense This article looks into the evolution of the Ekistics Theory as formulated by Constantinos A. Doxiadis for the drawing up of a concept of Network. Following the Delos Meetings, this theory, a science of human settlements, subsequently evolved into the idea of human activity networks and how they could apply to different fields, especially architecture and urbanism. Those meeting were held during cruises around the Greek Islands with intellectuals from different areas of knowledge and countries. , Moreover, Ekistics theory was used as a basic for the formulation of the Plan for Guanabara State, Brazil, whose launch in 1964 took place a few months after the first Delos Meeting in 1963. The plan was developed for Guanabara State following the transfer of the country’s capital from Rio de Janeiro to Brasília in 1960. Carlos Lacerda, the first elected governor, invited Doxiadis, hoping that by using technical instruments devised by the Greek architect and by relying on a foreign consultant, the plan would turn the city-state into a model of administration, apart from political pressures. The article highlights the rationality based on the Ekistics, strongly -

Cities and Their Vital Systems: Infrastructure Past, Present, and Future

Cities and Their Vital Systems: Infrastructure Past, Present, and Future i Series on Technology and Social Priorities NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING CitiesCitiesCities andandand TheirTheirTheir VitalVitalVital SystemsSystemsSystems Infrastructure Past, Present, and Future Jesse H. Ausubel and Robert Herman Editors NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C. 1988 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Cities and Their Vital Systems: Infrastructure Past, Present, and Future ii National Academy Press 2101 Constitution Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20418 NOTICE: The National Academy of Engineering was established in 1964, under the charter of the National Academy of Sciences, as a parallel organization of outstanding engineers. It is autonomous in its administration and in the selection of its members, sharing with the National Academy of Sci- ences the responsibility for advising the federal government. The National Academy of Engineering also sponsors engineering programs aimed at meeting national needs, encourages education and research, and recognizes the superior achievement of engineers. Dr. Robert M. White is president of the National Academy of Engineering. Funds for the National Academy of Engineering's Symposium Series on Technology and Social Priorities were provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, and the Academy's Technology Agenda Program. This publication has been reviewed by a group other than the authors according to procedures approved by a Report Review Committee. The views expressed in this volume are those of the authors and are not presented as the views of the Mellon Foundation, Carnegie Corporation, or the National Academy of Engineering. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cities and their vital systems. -

Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa

sustainability Article Between Village and Town: Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa Jytte Agergaard * , Susanne Kirkegaard and Torben Birch-Thomsen Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen, Oster Voldgade 13, DK-1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (T.B.-T.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In the next twenty years, urban populations in Africa are expected to double, while urban land cover could triple. An often-overlooked dimension of this urban transformation is the growth of small towns and medium-sized cities. In this paper, we explore the ways in which small towns are straddling rural and urban life, and consider how insights into this in-betweenness can contribute to our understanding of Africa’s urban transformation. In particular, we examine the ways in which urbanism is produced and expressed in places where urban living is emerging but the administrative label for such locations is still ‘village’. For this purpose, we draw on case-study material from two small towns in Tanzania, comprising both qualitative and quantitative data, including analyses of photographs and maps collected in 2010–2018. First, we explore the dwindling role of agriculture and the importance of farming, businesses and services for the diversification of livelihoods. However, income diversification varies substantially among population groups, depending on economic and migrant status, gender, and age. Second, we show the ways in which institutions, buildings, and transport infrastructure display the material dimensions of urbanism, and how urbanism is planned and aspired to. Third, we describe how well-established middle-aged households, independent women (some of whom are mothers), and young people, mostly living in single-person households, explain their visions and values of the ways in which urbanism is expressed in small towns. -

2017-Annual-Report.Pdf

2.1 million meals distributed Supporting Boroume at the Since 2012 THI has distributed over Farmer’s Market Program 2.1 million meals through our partners IOCC/Apostoli and SOS Villages Greece. THI Australia supports the Boroume at the Farmer’s Market Program, a dynamic community initiative that saves surplus food from farmers’ markets in Athens for 11 athletes supported distribution in local charities. THI is supporting 11 athletes each year from Greece and Cyprus as they prepare for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. MDA Hellas operations in Thessaloniki funded 180,000 meals served For 3 years now and working with MDA Hellas we fully fund the operations of THI is supporting Prolepsis/Diatrofi the organization’s unit in Thessaloniki, providing schoolchildren with daily offering daily services to patients meals. Since 2015 through a match suffering from 47 rare neuromuscular by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation disorders. we have served 180,000 meals to students whose families suffer from food insecurity and in some cases hunger. 62,797 gallons of heating fuel donated Establish the first ever transit Since 2014 we helped donate 62,797 centers gallons of heating fuel to a total of 59 social welfare institutions located in CRISIS RELIEF Working with METAdrasi THI has helped Northern Greece through our partners establish the first ever transit centers for IOCC/Apostoli. unaccompanied minors fleeing war in the Middle East located on the islands of Lesvos and Samos. 30,000 children supported each year 10,000 children vaccinated For a fourth consecutive year THI is Working with Doctors of the World we supporting “Together for Children,” an have vaccinated over 10,000 children. -

'The Planned City Sweeps the Poor Away...'§: Urban Planning and 21St Century Urbanisation

Progress in Planning 72 (2009) 151–193 www.elsevier.com/locate/pplann ‘The planned city sweeps the poor away...’§: Urban planning and 21st century urbanisation Vanessa Watson * School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, Cape Town 7700, South Africa Abstract In recent years, attention has been drawn to the fact that now more than half of the world’s population is urbanised, and the bulk of these urban dwellers are living in the global South. Many of these Southern towns and cities are dealing with crises which are compounded by rapid population growth, particularly in peri-urban areas; lack of access to shelter, infrastructure and services by predominantly poor populations; weak local governments and serious environmental issues. There is also a realisation that newer issues of climate change, resource and energy depletion, food insecurity and the current financial crisis will exacerbate present difficult conditions. As ideas that either ‘the market’ or ‘communities’ could solve these urban issues appear increasingly unrealistic, there have been suggestions for a stronger role for governments through reformed instruments of urban planning. However, agencies (such as UN-Habitat) promoting this make the point that in many parts of the world current urban planning systems are actually part of the problem: they serve to promote social and spatial exclusion, are anti-poor, and are doing little to secure environmental sustainability. Urban planning, it is argued, therefore needs fundamental review if it is to play any meaningful role in current urban issues. This paper explores the idea that urban planning has served to exclude the poor, but that it might be possible to develop new planning approaches and systems which address urban growth and the major environment and resource issues, and which are pro- poor. -

Obverse Reverse

obverse reverse 84 A Bronze Coin from Eleusis in the Kelsey Museum Eleusis, Greece, second half of the fourth century BCE Coin Bronze with dark greenish and brown patina, Diam. 1 cm; Thickness 0.2 cm; Weight 3.32 g Gift from the family of Dr. Abram Richards (after 1884), Kelsey Museum 26837 A group of 1,205 ancient coins from the collection of Dr. Abram Richards (1822–1884) was donated to the Univer- sity of Michigan in 1884 (typescript catalogue 1897); 856 of them eventually became part of the Kelsey Museum collection (typescript catalogue 1974).1 This essay focuses on a single coin from Eleusis from that collection. One side of the coin depicts a male seated on a winged car drawn by two serpents; in his right hand he holds two ears of grain. The other side shows a pig standing on some thin lines, most likely a bundle of twigs, to judge from better preserved parallels. Above the pig, barely legible, can be read Λ, Υ, Σ—part of ΕΛΕΥΣ (Eleusis). Below the bundle of twigs is a bull’s head. What is the meaning behind these images, and what were such coins used for? Eleusis, some 21 kilometers west of Athens and close to the sea, is now mainly known for the remains of a major sanctuary of Demeter and Kore. The sanctuary was excavated continuously between 1882 and the 1950s. On the basis of unpublished material from these excavations, Michael Cosmo- poulos (2003) argues that the earliest ritual activities at the site can be attested as early as the Late Bronze Age. -

Density Paper: Outline

Density in Urban Development 20 January 1996 This is a complete draft text prepared for Building Issues. A summarized version is published as Building Issues, 3/96. Vol 8, No 3 (http://www.hdm.lth.se/bi/report/frame.htm). Claudio Acioly Jr. Forbes Davidson IHS-Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies The authors The authors have been involved both through teaching and working with urban development issues in a wide range of countries. They have worked at project level and have first hand experience both of the power of local traditions and of bureaucratic inertia when any changes to the existing norms are proposed. Any change from the status quo is difficult. To support this it is hoped that the report provides a stimulus for critical thinking, arguments for change and access to useful material. Claudio Acioly Jr Claudio Acioly Jr . is an architect & urban planner with experience in planning, design, management, implementation and evaluation of housing and urban development projects. He has long-term experience in Brazil, The Netherlands and Guinea-Bissau and short-term missions in diverse countries. He is the author of two books on self-help housing and neighbourhood upgrading and several papers in international journals. In 1992, he earned his master degree in Design, Planning and Management of Buildings and the Built Environment at the Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands. Apart from consultancy works, he presently teaches in the IHS in the areas of planning and management of urban development programmes, urban renewal and human settlement upgrading, housing and community-based action planning. -

Ecumenopolis, the Inevitable City of the Future, by C. A

REVIEWS & NOTICES Earth Law Journal: Journal of International and Compa- should be of international interest—to inform those active rative Environmental Law,Edited by NICHOLAS A.ROBINSON. in the environmental field in one country of the theories and A. W. Sijthoff, Leyden, The Netherlands: Vol. 1, No. 1, practices being developed in other countries or at the inter- pp. 1-84, February 1975; Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 85-182, May national level'. 1975, 24.5 X 16.2 x 0.5 and 0.6 cm, respectively; Dfl. 82 / In form and style somewhere between a journal and a $35.75: single issue Dfl. 22 / $9.50; Quarterly. magazine, Environmental Policy and Law's first issue pro- vides an informative and pleasing new encounter for law- Environmental Policy and Law, Edited by MARTIN A. MAT- journal readers. The journal contains good, relevant pic- TES (Editor-in-Chief WOLFGANG E. BURHENNE). Elsevier tures and even some provocative cartoons. Its sponsor, Sequoia, Lausanne, Switzerland: Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 1-48, the International Council of Environmental Law, has thus June 1975; 27.1 x 20.0 x 0.3 cm, Sfr. 90 (or US $36.00, started a meritorious service toward its goal to develop the DM. 85.00, £15.25); Quarterly. interchange of information on legal, administrative, and The appearance of two journals devoted to legal issues policy, aspects of environmental conservation. provides a welcome sign of heightened awareness of the The sponsors and editors of both journals deserve high need for laws and institutions in the quest for international commendation for their pioneering moves to fill glaring environmental protection.