Globalization and Inequality Without Differences in Data Definition, Legal System and Other Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 2. Co-Investigators (Members of the China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group)

Appendix 2. Co-investigators (Members of the China Kadoorie Biobank collaborative group) Name Location Role Contribution Rory Collins, MBBS, University of Oxford, Oxford, International Steering Study design and MSc UK Committee coordination Richard Peto, MD, University of Oxford, Oxford, International Steering Study design and MSc UK Committee coordination Robert Clarke, MD, University of Oxford, Oxford, International Steering Study design and MSc UK Committee coordination Robin Walters, PhD University of Oxford, Oxford, International Steering Study design and UK Committee coordination Xiao Han, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination Can Hou, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination Biao Jing, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination Chao Liu, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination Pei Pei, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination Yunlong Tan, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination -

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road

PROCEEDINGS International Mogao Grottes Conference at Dunhuang on the Conservation of Conservation October of Grotto Sites 1993Mogao Grottes Ancient Sites at Dunhuang on the Silk Road October 1993 The Getty Conservation Institute Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road Proceedings of an International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites Conference organized by the Getty Conservation Institute, the Dunhuang Academy, and the Chinese National Institute of Cultural Property Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang The People’s Republic of China 3–8 October 1993 Edited by Neville Agnew THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE LOS ANGELES Cover: Four bodhisattvas (late style), Cave 328, Mogao grottoes at Dunhuang. Courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy. Photograph by Lois Conner. Dinah Berland, Managing Editor Po-Ming Lin, Kwo-Ling Chyi, and Charles Ridley, Translators of Chinese Texts Anita Keys, Production Coordinator Jeffrey Cohen, Series Designer Hespenheide Design, Book Designer Arizona Lithographers, Printer Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 © 1997 The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved The Getty Conservation Institute, an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust, works internation- ally to further the appreciation and preservation of the world’s cultural heritage for the enrichment and use of present and future generations. The listing of product names and suppliers in this book is provided for information purposes only and is not intended as an endorsement by the Getty Conservation Institute. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conservation of ancient sites on the Silk Road : proceedings of an international conference on the conservation of grotto sites / edited by Neville Agnew p. -

Summary of Mass Lead Poisoning Incidents

Summary of Mass Lead Poisoning Incidents Lead has been used for thousands of years in products including paints, gasoline, cosmetics, and even children’s toys, but lead battery production is by far the largest consumer of lead. Although chronic exposures to lead affect both children and adults, there have also been many reports of localized mass acute lead poisonings. Below we outline some of the largest lead poisoning incidents related to the manufacturing and recycling of lead batteries that have been reported since 1987. Shanghai, China 2011 Twenty-five children living in Kanghua New Village were found to have elevated blood lead levels. At least ten of these children were hospitalized for treatment. As a result, the Shanghai Environmental Protection Bureau shut down two factories for additional investigations that are reportedly located approximately 700 meters away from the village. One of the two factories was a lead battery manufacturing plant operated by the U.S. company, Johnson Controls. The other, Shanghai Xinmingyuan Automobile Accessory Co., made lead-containing wheel weights. Jiangsu Province, China 2011 One-third of the employees at Taiwanese-owned Changzhou Ri Cun Battery Technology Company in eastern Jiangsu province were found with elevated BLLs between 28- 48ug/dL. All employees of the lead battery plant were tested after a pregnant employee discovered through testing her BLL was twice the level of concern. Production at the factory was temporarily suspended. Yangxunqiao, Zhejiang Province, China 2011 More than 600 people (including 103 children) working in and living around a cluster of aluminum foil fabricating workshops were found with excessive blood lead levels (BLLs). -

Original Article Malocclusions in Xia Dynasty in China

Chinese Medical Journal 2012;125(1):119-122 119 Original article Malocclusions in Xia Dynasty in China WANG Wei, ZENG Xiang-long, ZHANG Cheng-fei and YANG Yan-qi Keywords: malocclusion; Xia Dynasty skulls; tooth crowding; diastema; individual tooth malposition Background The prevalence of malocclusion in modern population is higher than that in the excavated samples from the ancient times. Presently, the prevalence of juvenile malocclusion in the early stage of permanent teeth is as high as 72.92% in China. This study aimed to observe and evaluate the prevalence and severity of malocclusions in a sample of Xia Dynasty in China, and to compare these findings with the modern Chinese population. Methods The material consisted of 38 male and 18 female protohistoric skulls of Xia Dynasty 4000 years ago. Of 86 dental arches, 29 cases had the jaw relationships. Tooth crowding, diastema, individual tooth malposition and malocclusion were studied. Results Of the samples, 23.3% showed tooth alignment problems including crowding (8.1%), diastema (9.3%), and individual tooth malposition (5.8%). The prevalence of malocclusion was 27.6%, mainly presented as Angle Class I. Conclusions It is indicated that over thousands of years from Neolithic Age (6000–7000 years ago) to Xia Dynasty (4000 years ago), the prevalence of malocclusion did not change significantly. The prevalence of malocclusion of Xia Dynasty samples was much lower than that of modern population. Chin Med J 2012;125(1):119-122 alocclusion is defined as any deviation from the diastema, individual tooth malposition and malocclusion M normal or ideal relationship of the maxillary and of skull samples of Xia Dynasty excavated in Er-li-tou mandibular teeth, as they are brought into functional site in Henan Province and You-yao site in Shanxi contact. -

Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (11 Wastewater Management and Water Supply Subprojects)

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 34473-01 February 2006 PRC: Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (11 Wastewater Management and Water Supply Subprojects) Prepared by Henan Provincial Government for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 02 February 2006) Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.12 $1.00 = CNY8.06 The CNY exchange rate is determined by a floating exchange rate system. In this report a rate of $1.00 = CNY8.27 is used. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BOD – biochemical oxygen demand COD – chemical oxygen demand CSC – construction supervision company DI – design institute EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMC – environmental management consultant EMP – environmental management plan EPB – environmental protection bureau GDP – gross domestic product HPG – Henan provincial government HPMO – Henan project management office HPEPB – Henan Provincial Environmental Protection Bureau HRB – Hai River Basin H2S – hydrogen sulfide IA – implementing agency LEPB – local environmental protection bureau N – nitrogen NH3 – ammonia O&G – oil and grease O&M – operation and maintenance P – phosphorus pH – factor of acidity PMO – project management office PM10 – particulate -

Of the Chinese Bronze

READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Ar chaeolo gy of the Archaeology of the Chinese Bronze Age is a synthesis of recent Chinese archaeological work on the second millennium BCE—the period Ch associated with China’s first dynasties and East Asia’s first “states.” With a inese focus on early China’s great metropolitan centers in the Central Plains Archaeology and their hinterlands, this work attempts to contextualize them within Br their wider zones of interaction from the Yangtze to the edge of the onze of the Chinese Bronze Age Mongolian steppe, and from the Yellow Sea to the Tibetan plateau and the Gansu corridor. Analyzing the complexity of early Chinese culture Ag From Erlitou to Anyang history, and the variety and development of its urban formations, e Roderick Campbell explores East Asia’s divergent developmental paths and re-examines its deep past to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of China’s Early Bronze Age. Campbell On the front cover: Zun in the shape of a water buffalo, Huadong Tomb 54 ( image courtesy of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Institute for Archaeology). MONOGRAPH 79 COTSEN INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY PRESS Roderick B. Campbell READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Archaeology of the Chinese Bronze Age From Erlitou to Anyang Roderick B. Campbell READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press Monographs Contributions in Field Research and Current Issues in Archaeological Method and Theory Monograph 78 Monograph 77 Monograph 76 Visions of Tiwanaku Advances in Titicaca Basin The Dead Tell Tales Alexei Vranich and Charles Archaeology–2 María Cecilia Lozada and Stanish (eds.) Alexei Vranich and Abigail R. -

Thomas David Dubois

East Asian History NUMBER 36 . DECEMBER 2008 Institute of Advanced Studies The Australian National University ii Editor Benjamin Penny Editorial Assistants Lindy Shultz and Dane Alston Editorial Board B0rge Bakken John Clark Helen Dunstan Louise Edwards Mark Elvin Colin Jeffcott Li Tana Kam Louie Lewis Mayo Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Kenneth Wells Design and Production Oanh Collins and Lindy Shultz Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the thilty-sixth issue of East Asian History, printed in July 2010. It continues the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. This externally refereed journal is published twice per year. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian Hist01Y College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 2 6125 2346 Fax +61 2 6125 5525 Email [email protected] Website http://rspas.anu.edu.au/eah/ ISSN 1036-D008 iii CONTENTS 1 Editor's note Benjamin Penny 3 Manchukuo's Filial Sons: States, Sects and the Adaptation of Graveside Piety Thomas David DuBois 29 New Symbolism and Retail Therapy: Advertising Novelties in Korea's Colonial Period Roald Maliangkay 55 Landscape's Mediation Between History and Memory: A Revisualization of Japan's (War-Time) Past julia Adeney Thomas 73 The Big Red Dragon and Indigenizations of Christianity in China Emily Dunn Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing ��g�p, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover image 0 Chi-ho ?ZmJ, South-Facing House (Minamimuki no ie F¥iIoJO)�O, 1939. Oil on canvas, 79 x 64 cm. Collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Korea MANCHUKUO'S FILIAL SONS: STATES, SECTS AND THE ADAPTATION OF GRAVESIDE PIETY � ThomasDavid DuBois On October 23, 1938, Li Zhongsan *9='=, known better as Filial Son Li This paper was presented at the Research (Li Xiaozi *$':r), emerged from the hut in which he had lived fo r three Seminar Series at Hong Kong University, 4 October, 2007 and again at the <'Religious years while keeping watch over his mother's grave. -

Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility)

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 39321 June 2008 PRC: Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility) Prepared by: ANZDEC Limited Australia For Shaanxi Province Development and Reform Commission This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. FINAL REPORT SHAANXI QINLING BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND DEMONSTRATION PROJECT PREPARED FOR Shaanxi Provincial Government And the Asian Development Bank ANZDEC LIMITED September 2007 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as at 1 June 2007) Currency Unit – Chinese Yuan {CNY}1.00 = US $0.1308 $1.00 = CNY 7.64 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BAP – Biodiversity Action Plan (of the PRC Government) CAS – Chinese Academy of Sciences CASS – Chinese Academy of Social Sciences CBD – Convention on Biological Diversity CBRC – China Bank Regulatory Commission CDA - Conservation Demonstration Area CNY – Chinese Yuan CO – company CPF – country programming framework CTF – Conservation Trust Fund EA – Executing Agency EFCAs – Ecosystem Function Conservation Areas EIRR – economic internal rate of return EPB – Environmental Protection Bureau EU – European Union FIRR – financial internal rate of return FDI – Foreign Direct Investment FYP – Five-Year Plan FS – Feasibility -

Spatiotemporal Evolution of Population in Northeast China During 2012–2017: a Nighttime Light Approach

Hindawi Complexity Volume 2020, Article ID 3646145, 12 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3646145 Research Article Spatiotemporal Evolution of Population in Northeast China during 2012–2017: A Nighttime Light Approach Haolin You,1 Cui Jin ,1 and Wei Sun 2 1Key Laboratory of Physical Geography and Geomatics, Liaoning Normal University, 116029 Dalian, China 2Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Key Laboratory of Watershed Geographic Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China Correspondence should be addressed to Cui Jin; [email protected] and Wei Sun; [email protected] Received 5 April 2020; Accepted 7 May 2020; Published 28 May 2020 Guest Editor: Wen-Ze Yue Copyright © 2020 Haolin You et al. +is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Population is one of the key problematic factors that are restricting China’s economic and social development. Previous studies have used nighttime light (NTL) imagery to calculate population density. +is study analyzes the spatiotemporal evolution of the population in Northeast China based on linear regression analyses of NPP-VIIRS NTL imagery and statistical population data from 36 cities in Northeast China from 2012 to 2017. Based on a comparison of the estimation results in different years, we observed the following. (1) +e population of Northeast China showed an overall decreasing trend from 2012–2017, with population changes of +31,600, −960,800, −359,800, −188,000, and −1,127,600 in the respective years. (2) With the overall population loss trend in Northeast China, the population increased in only three cities, namely, Shenyang, Dalian, and Panjin, with an average increase during the six-year period of 24,200, 6,500, and 2,000 people, respectively. -

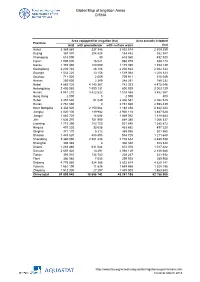

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

The Transition of the Kuomintang Government's Policies Towards

International Journal of Korean History (Vol.20 No.2, Aug. 2015) 153 a 1946: The Transition of the Kuomintang Government’s Policies towards Korean Immigrants in Northeast China* Zhang Muyun** Introduction Currently, the research on the Kuomintang Government’s policies to- wards Korean immigrants has gradually increased. Scholars have attached great importance to the use of archival resources in Shanghai, Tianjin, Peking, Wuhan and Liaoning. Yang Xiaowen1 (2008) made use of the original records to discuss post-war China’s policies towards the repatria- tion of Korean immigrants in the Wuhan area. Ma Jun, Shan Guanchu2 (2006) adequately utilized Zhongguo diyu hanren tuanti guanxi shiliao * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 3rd Annual Korea University Korean History Graduate Student Conference, 2015, Korea University. I thank my discussant and conference participants for valuable discussions. I also appreciate the IJKH reviewers for very helpful comments. ** MA student, Major in history of modern China, School of Marxism, Tsinghua University. 1 Yang Xiaowen. “Zhanhou zhongguo guannei hanren de jizhong qianfan zhengce ji qi shijian yanjiu: yi wuhan wei gean fenxi” (the post-war Chinese’s policies to- wards repatriation of Korean immigrants in Wuhan area) (Master diss., Fudan University, 2008). 2 Ma Jun, Shan Guanchu. “Zhanhou guomin zhengfu qianfan hanren zhengce de yanbian ji zai shanghai diqu de shijian” (the development of the Kuomintang gov- ernment’s policies towards repatriation of Korean immigrants in Shanghai area), Shilin, 2006(2). 154 1946: The Transition of the Kuomintang Government’s Policies ~ huibian3(the Comprehensive Collection of Archival Papers on Korean immigrants’ organizations in China) to investigate the development of the Kuomintang government’s policies towards the repatriation of Korean immigrants in the Shanghai area.