Original Article Malocclusions in Xia Dynasty in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 2. Co-Investigators (Members of the China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group)

Appendix 2. Co-investigators (Members of the China Kadoorie Biobank collaborative group) Name Location Role Contribution Rory Collins, MBBS, University of Oxford, Oxford, International Steering Study design and MSc UK Committee coordination Richard Peto, MD, University of Oxford, Oxford, International Steering Study design and MSc UK Committee coordination Robert Clarke, MD, University of Oxford, Oxford, International Steering Study design and MSc UK Committee coordination Robin Walters, PhD University of Oxford, Oxford, International Steering Study design and UK Committee coordination Xiao Han, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination Can Hou, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination Biao Jing, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination Chao Liu, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination Pei Pei, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination Yunlong Tan, BSc Chinese Academy of Medical Member of National Co- Data cleaning, verification, Sciences, Beijing, China ordinating Centre, Beijing and coordination -

Summary of Mass Lead Poisoning Incidents

Summary of Mass Lead Poisoning Incidents Lead has been used for thousands of years in products including paints, gasoline, cosmetics, and even children’s toys, but lead battery production is by far the largest consumer of lead. Although chronic exposures to lead affect both children and adults, there have also been many reports of localized mass acute lead poisonings. Below we outline some of the largest lead poisoning incidents related to the manufacturing and recycling of lead batteries that have been reported since 1987. Shanghai, China 2011 Twenty-five children living in Kanghua New Village were found to have elevated blood lead levels. At least ten of these children were hospitalized for treatment. As a result, the Shanghai Environmental Protection Bureau shut down two factories for additional investigations that are reportedly located approximately 700 meters away from the village. One of the two factories was a lead battery manufacturing plant operated by the U.S. company, Johnson Controls. The other, Shanghai Xinmingyuan Automobile Accessory Co., made lead-containing wheel weights. Jiangsu Province, China 2011 One-third of the employees at Taiwanese-owned Changzhou Ri Cun Battery Technology Company in eastern Jiangsu province were found with elevated BLLs between 28- 48ug/dL. All employees of the lead battery plant were tested after a pregnant employee discovered through testing her BLL was twice the level of concern. Production at the factory was temporarily suspended. Yangxunqiao, Zhejiang Province, China 2011 More than 600 people (including 103 children) working in and living around a cluster of aluminum foil fabricating workshops were found with excessive blood lead levels (BLLs). -

Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (11 Wastewater Management and Water Supply Subprojects)

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 34473-01 February 2006 PRC: Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (11 Wastewater Management and Water Supply Subprojects) Prepared by Henan Provincial Government for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 02 February 2006) Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.12 $1.00 = CNY8.06 The CNY exchange rate is determined by a floating exchange rate system. In this report a rate of $1.00 = CNY8.27 is used. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BOD – biochemical oxygen demand COD – chemical oxygen demand CSC – construction supervision company DI – design institute EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMC – environmental management consultant EMP – environmental management plan EPB – environmental protection bureau GDP – gross domestic product HPG – Henan provincial government HPMO – Henan project management office HPEPB – Henan Provincial Environmental Protection Bureau HRB – Hai River Basin H2S – hydrogen sulfide IA – implementing agency LEPB – local environmental protection bureau N – nitrogen NH3 – ammonia O&G – oil and grease O&M – operation and maintenance P – phosphorus pH – factor of acidity PMO – project management office PM10 – particulate -

Of the Chinese Bronze

READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Ar chaeolo gy of the Archaeology of the Chinese Bronze Age is a synthesis of recent Chinese archaeological work on the second millennium BCE—the period Ch associated with China’s first dynasties and East Asia’s first “states.” With a inese focus on early China’s great metropolitan centers in the Central Plains Archaeology and their hinterlands, this work attempts to contextualize them within Br their wider zones of interaction from the Yangtze to the edge of the onze of the Chinese Bronze Age Mongolian steppe, and from the Yellow Sea to the Tibetan plateau and the Gansu corridor. Analyzing the complexity of early Chinese culture Ag From Erlitou to Anyang history, and the variety and development of its urban formations, e Roderick Campbell explores East Asia’s divergent developmental paths and re-examines its deep past to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of China’s Early Bronze Age. Campbell On the front cover: Zun in the shape of a water buffalo, Huadong Tomb 54 ( image courtesy of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Institute for Archaeology). MONOGRAPH 79 COTSEN INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY PRESS Roderick B. Campbell READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Archaeology of the Chinese Bronze Age From Erlitou to Anyang Roderick B. Campbell READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press Monographs Contributions in Field Research and Current Issues in Archaeological Method and Theory Monograph 78 Monograph 77 Monograph 76 Visions of Tiwanaku Advances in Titicaca Basin The Dead Tell Tales Alexei Vranich and Charles Archaeology–2 María Cecilia Lozada and Stanish (eds.) Alexei Vranich and Abigail R. -

Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility)

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 39321 June 2008 PRC: Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility) Prepared by: ANZDEC Limited Australia For Shaanxi Province Development and Reform Commission This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. FINAL REPORT SHAANXI QINLING BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND DEMONSTRATION PROJECT PREPARED FOR Shaanxi Provincial Government And the Asian Development Bank ANZDEC LIMITED September 2007 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as at 1 June 2007) Currency Unit – Chinese Yuan {CNY}1.00 = US $0.1308 $1.00 = CNY 7.64 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BAP – Biodiversity Action Plan (of the PRC Government) CAS – Chinese Academy of Sciences CASS – Chinese Academy of Social Sciences CBD – Convention on Biological Diversity CBRC – China Bank Regulatory Commission CDA - Conservation Demonstration Area CNY – Chinese Yuan CO – company CPF – country programming framework CTF – Conservation Trust Fund EA – Executing Agency EFCAs – Ecosystem Function Conservation Areas EIRR – economic internal rate of return EPB – Environmental Protection Bureau EU – European Union FIRR – financial internal rate of return FDI – Foreign Direct Investment FYP – Five-Year Plan FS – Feasibility -

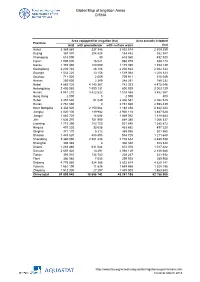

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

Central China Securities Co., Ltd

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. Central China Securities Co., Ltd. (a joint stock company incorporated in 2002 in Henan Province, the People’s Republic of China with limited liability under the Chinese corporate name “中原證券股份有限公司” and carrying on business in Hong Kong as “中州證券”) (Stock Code: 01375) ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2017 The board (the “Board”) of directors (the “Directors”) of Central China Securities Co., Ltd. (the “Company”) hereby announces the audited annual results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended 31 December 2017. This annual results announcement, containing the full text of the 2017 annual report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcements of annual results and have been reviewed by the audit committee of the Company. The printed version of the Company’s 2017 annual report will be dispatched to the shareholders of the Company and available for viewing on the website of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited at www.hkexnews.hk, the website of the Shanghai Stock Exchange at www.sse.com.cn and the website of the Company at www.ccnew.com around mid-April 2018. -

Chemoradiation Versus Oesophagectomy for Locally

Jia et al. Trials (2019) 20:206 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3316-5 STUDY PROTOCOL Open Access Chemoradiation versus oesophagectomy for locally advanced oesophageal cancer in Chinese patients: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial Ruinuo Jia1,2, Weijiao Yin1, Shuoguo Li1, Ruonan Li1, Junqiang Yang1, Tanyou Shan1, Dan Zhou1, Wei Wang1, Lixin Wan3, Fuyou Zhou4 and Shegan Gao1* Abstract Background: Surgery is the gold standard treatment for local advanced disease, while definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy (DCRT) is recommended for those who are medically unable to tolerate major surgery or medically fit patients who decline surgery. The primary aim of this trial is to compare the outcomes in Chinese patients with oesophageal squamous cell cancer with locally advanced resectable disease who have received either surgery or DCRT. Methods/design: One hundred ninety-six patients with T1bN + M0 or T2-4aN0-2 M0 oesophageal squamous cell cancer will be randomised to the DCRT group or the surgery group. In the DCRT group, patients will be given intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) with 50 Gy/25 fractions and basic chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil regimens. In the surgery group, patients will receive neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NCRT) and standard oesophagectomy. Five years of follow-up will be scheduled for patients. The primary endpoints are 2-year/5-year overall survival; the secondary endpoints are 2-year/5-year progression-free survival, treatment- related adverse events and the patients’ quality of life. The main evaluation methods include oesophagoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography and biopsy, oesophageal barium meal, computed tomography, positron emission tomography-computed tomography, blood tests and questionnaires. -

Heavy Metals Distribution, Sources, and Ecological Risk Assessment in Huixian Wetland, South China

water Article Heavy Metals Distribution, Sources, and Ecological Risk Assessment in Huixian Wetland, South China Liangliang Huang 1,2 , Saeed Rad 1,* , Li Xu 1,3, Liangying Gui 4, Xiaohong Song 2, Yanhong Li 1, Zhiqiang Wu 3 and Zhongbing Chen 5,* 1 College of Environmental Science and Engineering, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin 541004, China; [email protected] (L.H.); [email protected] (L.X.); [email protected] (Y.L.) 2 Guangxi Key Laboratory of Environmental Pollution Control and Technology, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin 541004, China; [email protected] 3 Coordinated Innovation Center of Water Pollution Control and Water Security in Karst Area, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin 541004, China; [email protected] 4 College of Tourism and Landscape Architecture, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin 541004, China; [email protected] 5 Department of Applied Ecology, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Kamýcká 129, 16521 Prague, Czech Republic * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.R.); [email protected] (Z.C.); Tel.: +86-773-253-6372 (S.R.); +42-022-438-2994 (Z.C.) Received: 30 November 2019; Accepted: 3 February 2020; Published: 6 February 2020 Abstract: This research has focused on the source identification, concentration, and ecological risk assessment of eight heavy metals in the largest karst wetland (Huixian) of south China. Numerous samples from superficial soil and sediment within ten representative landuse types were collected and examined, and the results were analyzed using multiple methods. Single pollution index (Pi) results were underpinned by the Geoaccumulation index (Igeo) method, in which Cd was observed as the priority pollutant with the highest contamination degree in this area. -

Changes of Tgfb1 and Tgfbrii Expression in Esophageal Precancerous and Cancerous Lesions: a Study of a High-Risk Population in Henan, Northern China

Diseases of the Esophagus (2002) 15, 74–79 Ó 2002 ISDE/Blackwell Publishing Asia http://www.paper.edu.cn Original article Changes of TGFb1 and TGFbRII expression in esophageal precancerous and cancerous lesions: a study of a high-risk population in Henan, northern China Q. Zhou,1 L. Dong Wang,1,2 F. Du,1 Y. Zhou,3 Y. Rui Zhang,4 B. Liu,5 C. Wei Feng,6 S. Shan Gao,1 Z. Min Fan,1 C. S. Yang,7 S. Zheng2 1Laboratory for Cancer Research, College of Medicine, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan; 2Cancer Institute, Zhejing University, Hangzhou, China; 3Department of Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University and 4Department of Gastroenterology, Henan Province Hospital, Zhengzhou, Henan; 5Department of Gastroenterology, Tong Ren Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing; 6Department of Gastroenterology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan, China; 7Laboratory for Cancer Research, College of Pharmacy, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ, USA SUMMARY. The level of transforming growth factor b1 (TGFb1) and transforming growth factor bII receptor (TGFbRII) was determined immunohistochemically in normal tissues and tissues with different severities of lesions (basal cell hyperplasia, BCH; dysplasia, DYS; carcinoma in situ, CIS; and squamous cell carcinoma, SCC) from surgically resected human esophagi and esophageal biopsies of symptom-free subjects. The samples were from an area with high esophageal cancer incidence in northern China (Linzhou, formerly Linxian, and nearby county Huixian in Henan Province). Peroxidase immunostain (ABC) and conventional hematoxylin and eosin stain were used. The tissue sections were incubated with antibodies of TGFb1 and TGFbRII overnight. The immunoreactivity was observed in cytoplasm of the esophageal specimen. -

In-Situ Stress Partition and Its Implication on Coalbed Methane Occurrence in the Basin–Mountain Transition Zone: a Case Study of the Pingdingshan Coalfield, China

Sådhanå (2020) 45:47 Ó Indian Academy of Sciences https://doi.org/10.1007/s12046-020-1278-7Sadhana(0123456789().,-volV)FT3](0123456789().,-volV) In-situ stress partition and its implication on coalbed methane occurrence in the basin–mountain transition zone: a case study of the Pingdingshan coalfield, China JIANGWEI YAN1,2,3, TIANRANG JIA1,2,3,*, GUOYING WEI1,2,4,*, MINGJIE ZHANG1,2 and YIWEN JU5 1 State Key Laboratory Cultivation Base for Gas Geology and Gas Control, Henan Polytechnic University, Jiaozuo 454003, China 2 College of Safety Science and Engineering, Henan Polytechnic University, Jiaozuo 454003, China 3 Collaborative Innovation Center of Coalbed Methane and Shale Gas for Central Plains Economic Region, Jiaozuo 454003, Henan Province, China 4 Collaborative Innovation Center of Coal Safety Production of Henan Province, Jiaozuo 454003, China 5 Key Laboratory of Computational Geodynamics, College of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] MS received 25 June 2019; revised 2 December 2019; accepted 5 December 2019 Abstract. The basin–mountain transition zone presents complex geologic structures and non-uniformly dis- tributed in-situ stress. Studying the spatial distribution laws of in-situ stress and their influences on coalbed methane (CBM) occurrence in coal seams plays a significant role in CBM extraction and prevention of coalmine disasters. Based on the actual measured in-situ stress data, CBM content and gas pressure data in the Pingdingshan coalfield, located in the basin–mountain transition zone in the south of the late Palaeozoic basins in the North China block, this research investigated the distribution characteristics of geologic structures and partition of in-situ stress as well as the effects of in-situ stresses on CBM occurrence in the research area using evolution theories of geologic structure and a statistical analysis method. -

Buddhist State Monasteries in Early Medieval China and Their Impact on East Asia Liqun He

Buddhist State Monasteries in Early Medieval China and their Impact on East Asia A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Philosophy of Heidelberg University in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of East Asian Art History by Liqun He December, 2013 Dissertation Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Lothar Ledderose; Prof. Dr. Sarah E. Fraser Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 1. Research topic ........................................................................................................... 1 2. Previous research on the layout of Buddhist monasteries in Early Medieval China ....................................................................................................................................... 5 3. The significance of the topic and research methods.................................................. 9 Chapter I - Monastery Layout in Early Medieval China: Textual Evidence ...... 15 1. The introduction of Buddhism and the establishment of early monasteries in China ..................................................................................................................................... 15 2. Buddhist monasteries in the Northern and Southern Dynasties .............................. 21 3. Buddhist monastery system during the Sui and Tang Dynasties............................. 25 Chapter II - Monastery Layout in Early Medieval China: Archaeological Evidence ....................................................................................................................