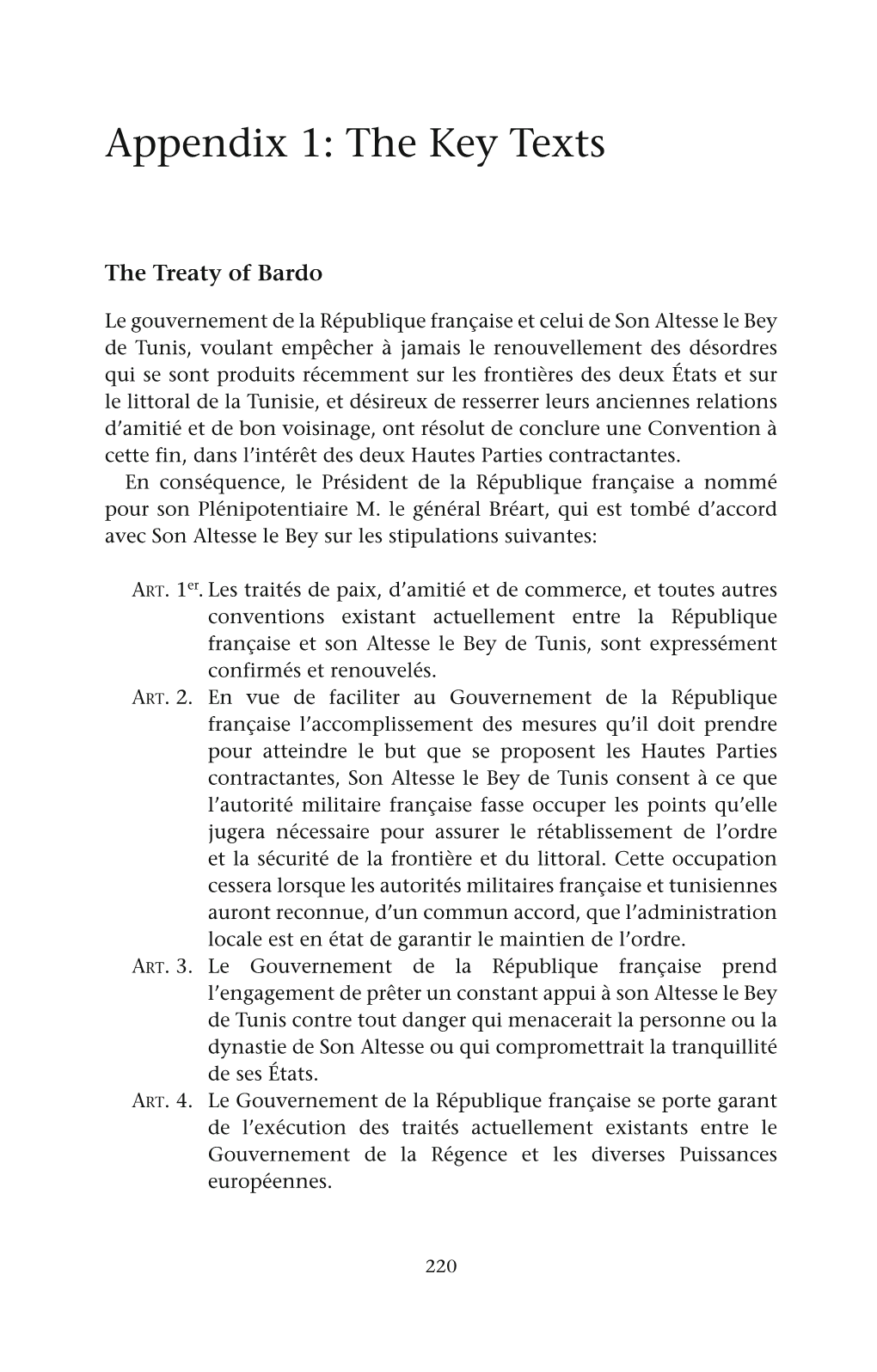

Appendix 1: the Key Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tunisian Islamism Beyond Democratization

Tunisian Islamism beyond Democratization Fabio Merone Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Political and Social Sciences Promotor: Prof. dr. Sami Zemni 1 Acknowledgments This dissertation is the outcome of several years of work and research. Such an achievement is not possible without the help and support of many people. First and foremost, I wish to present my special thanks to Pr. Francesco Cavatorta. He met me in Tunisia and stimulated this research project. He was a special assistant and colleague throughout the long path to the achievement of this work. I would like to show my gratitude in the second place to a special person who enjoyed to be called Abou al-Mouwahed. He was my privileged guide to the world of the Salafist sahwa (revival) and of its young constituency. Thirdly, I would like to pay my regards to my supervisor, pr. Sami Zemni, that proposed to join the friendly and intellectually creative MENARG group and always made me feel an important member of it. I would like to thank also all those whose assistance proved to be a milestone in the accomplishment of my end goal, in particular to all Tunisians that shared with me the excitement and anxiety of that period of amazing historical transformation. Last, but not least, I would like to show my warm thank to my sweet daughter that grew up together with this research, and my wife, both paying sometimes the prize of a hard and tiring period of life. This research project was funded in several periods. -

Eesti Sõjaajaloo Aastaraamat Estonian Yearbook of Military History

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Tallinn University: Open Journal5 Systems(11) / 2015Tallinna Ülikool Eesti sõjaajaloo aastaraamat ESTONIAN YEARBOOK OF MILITARY HISTORY I MAAILMASÕDA IDA-EUROOPAS – TeiSTSUGUNE KOGEMUS, TeiSTSUGUSED MÄLESTUSED Great War in Eastern Europe – Different Experience, Different Memories Eesti Sõjamuuseum Tallinna Ülikooli Kirjastus Viimsi–Tallinn 2015 Eesti sõjaajaloo aastaraamat 5 (11) 2015 I maailmasõda Ida-Euroopas – teistsugune kogemus, teistsugused mälestused Estonian Yearbook of Military History 5 (11) 2015 Great War in Eastern Europe – Different Experience, Different Memories Eesti sõjaajaloo aastaraamatu eelkäija on Eesti Sõjamuuseumi – Kindral Laidoneri Muuseumi aastaraamat (ilmus 2001–2007, ISSN 1406-7625) Kolleegium: dr Karsten Brüggemann, dr Ago Pajur, dr Oula Silvennoinen, dr Seppo Zetterberg, dr Tõnu Tannberg Eesti sõjaajaloo aastaraamatu artiklid on eelretsenseeritud Kaanel: I maailmasõja ajal vangilangenud Austria ohvitser vaguni aknal. Aleksander Funki (1884–1940) foto (EFA.231.0-58375). Tartust pärit Aleksander Funk teenis I maailmasõjas keisrinna Aleksandra Fjodorovna Tsarskoje Selo väli-sanitarrongi nr 143 fotograafina. Peatoimetaja: Toomas Hiio Toimetaja: Sandra Niinepuu Tõlked inglise ja saksa keelest: Sandra Niinepuu ja Toomas Hiio Resümeede tõlge: Alias Tõlkeagentuur OÜ Keeletoimetaja: Kristel Ress (Päevakera tekstibüroo) Autoriõigus: Eesti Sõjamuuseum – Kindral Laidoneri Muuseum, Tallinna Ülikooli Kirjastus ja autorid, 2015 ISSN 2228-0669 Eesti Sõjamuuseum – Kindral Laidoneri Muuseum Mõisa tee 1 74001 Viimsi, Harjumaa www.esm.ee Tallinna Ülikooli Kirjastus Narva mnt 25 10120 Tallinn www.tlupress.com Trükk: Pakett Sisukord Saateks (Toomas Hiio) .................................................................................... 5 I MAAILMASÕDA IDA-EUROOPAS – tEISTSUGUNE KOGEMUS, TEISTSUGUSED MÄLESTUSED Igor Kopõtin Esimese maailmasõja algus Eestis. Võim ja ühiskond.............................. 11 Beginning of the First World War in Estonia. -

From Le Monde (9 May 1975)

'The dawn of Europe' from Le Monde (9 May 1975) Caption: In an article published in the French daily newspaper Le Monde on the 25th anniversary of the Declaration made on 9 May 1950, Pierre Uri, former colleague of Jean Monnet, recalls the preparations for the Schuman Plan. Source: Le Monde. dir. de publ. FAUVET, Jacques. 09.05.1975, n° 9 427. Paris: Le Monde. "L'aube de l'Europe", auteur:Uri, Pierre , p. 1; 4. Copyright: (c) Translation CVCE.EU by UNI.LU All rights of reproduction, of public communication, of adaptation, of distribution or of dissemination via Internet, internal network or any other means are strictly reserved in all countries. Consult the legal notice and the terms and conditions of use regarding this site. URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/the_dawn_of_europe_from_le_monde_9_may_1975- en-16782668-a5de-470c-998e-56739fe3c07c.html Last updated: 06/07/2016 1/4 The 25th anniversary of the ‘Schuman Plan’ The dawn of Europe 9 May 1950 — ‘Today, Wednesday 9 May, at 5 p.m. in the Salon de l’Horloge at the Quai d’Orsay, the Minister of Foreign Affairs will make an important announcement.’ There, in a room bursting at the seams, a tall, frail man, speaking quietly with an eastern accent, acquainted his audience with the document that was to be relayed all over the world by telephone and wireless. Robert Schuman was rectitude and intrepid conviction personified: this was the source of that coolness which he had displayed when, as President of the Council in 1947, he had been confronted with a national strike. -

France and the German Question, 1945–1955

CreswellFrance and and the Trachtenberg German Question France and the German Question, 1945–1955 ✣ What role did France play in the Cold War, and how is French policy in that conºict to be understood? For many years the prevailing as- sumption among scholars was that French policy was not very important. France, as the historian John Young points out, was “usually mentioned in Cold War histories only as an aside.” When the country was discussed at all, he notes, it was “often treated as a weak and vacillating power, obsessed with outdated ideas of a German ‘menace.’”1 And indeed scholars often explicitly argued (to quote one typical passage) that during the early Cold War period “the major obsession of French policy was defense against the German threat.” “French awareness of the Russian threat,” on the other hand, was sup- posedly “belated and reluctant.”2 The French government, it was said, was not eager in the immediate postwar period to see a Western bloc come into being to balance Soviet power in Europe; the hope instead was that France could serve as a kind of bridge between East and West.3 The basic French aim, according to this interpretation, was to keep Germany down by preserving the wartime alliance intact. Germany itself would no longer be a centralized state; the territory on the left bank of the Rhine would not even be part of Germany; the Ruhr basin, Germany’s industrial heartland, would be subject to allied control. Those goals, it was commonly assumed, were taken seriously, not just by General Charles de Gaulle, who headed the French provisional government until Jan- uary 1946, but by Georges Bidault, who served as foreign minister almost without in- terruption from 1944 through mid-1948 and was the most important ªgure in French foreign policy in the immediate post–de Gaulle period. -

Datum: 19. 6. 2013 Projekt: Využití ICT

Datum: 19. 6. 2013 Projekt: Využití ICT techniky především v uměleckém vzdělávání Registrační číslo: CZ.1.07/1.5.00/34.1013 Číslo DUM: VY_32_INOVACE_433 Škola: Akademie ‐ VOŠ, Gymn. a SOŠUP Světlá nad Sázavou Jméno autora: Petr Vampola Název sady: Francie včera, dnes a zítra –reálie pro 4. ročník čtyřletých gymnázií. Název práce: LA FRANCE – SOUVERAINS ET CHEFS D´ÉTAT (prezentace) Předmět: Francouzský jazyk Ročník: IV. Studijní obor: 79‐41‐K/41 Gymnázium Časová dotace: 25 min. Vzdělávací cíl: Žák bude schopen se orientovat v historických faktech a obohatí si slovní zásobu. Pomůcky: PC a dataprojektor pro učitele Poznámka: Tento materiál je součástí tematického balíčku Francie včera, dnes a zítra. Inovace: Posílení mezipředmětových vztahů, využití multimediální techniky, využití ICT. SOUVERAINS ET CHEFS D´ETAT Hugues Capet (987-996) Robert II le Pieux (996-1031) Henri Ier (1031-1060) Philippe Ier (1060-1108) Louis VI le Gros (1108-1137) Louis VII le Jeune (1137-1180) Philippe II Auguste (1180-1223) Louis VIII le Lion (1223-1226) Louis IX (Saint Louis) (1226-1270) Philippe III le Hardi (1270-1285) Philippe IV le Bel (1285-1314) Louis X le Hutin (1314-1316) Jean Ier le Posthume (1316) Philippe V le Long (1316-1322) Charles IV le Bel (1322-1328) Philippe VI (1328-1350) Jean II le Bon (1350-1364) Charles V le Sage (1364-1380) Charles VI (1380-1422) Charles VII (1422-1461) Louis XI (1461-1483) Charles VIII (1483-1498) Louis XII (1498-1515) François Ier (1515-1547) Henri II (1547-1559) François II (1559-1560) Charles IX (1560-1574) -

Fonds Georges Bidault (Xxe Siècle)

Fonds Georges Bidault (XXe siècle) Répertoire (457AP/1-457AP/138) Par J. Irigoin, P. Gillet Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 1993 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_003630 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé en 2012 par l'entreprise diadeis dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) Préface AVANT-PROPOS L'histoire ne saurait s'écrire sans ces archives qui procèdent de l'activité des services publics et qui constituent les fonds de nos archives publiques, nationales, départementales ou communales. C'est là que l'on trouve la continuité, dans la diversité des actions menées. Mais elle ne saurait non plus se passer des papiers privés que les acteurs de premier rang ont constitués au long de leur vie et qui reflètent la part personnelle qu'ils ont prise dans les différentes fonctions qu'ils ont assumées. Grâce à de tels papiers, l'historien saura mieux discerner ce qu'ont été les chemins de la décision ou les voies de la négociation. Il comprendra mieux en quelle mesure et dans quel sens la réflexion et la volonté d'un homme ont orienté le destin des autres. L'art de gouverner demeure, même à l'âge de l'ordinateur, une affaire de personnalité, et l'histoire se désincarne si elle néglige le profil de ceux qui l'ont faite avant qu'on ne l'écrive. -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

The Development of Libyan- Tunisian Bilateral Relations: a Critical Study on the Role of Ideology

THE DEVELOPMENT OF LIBYAN- TUNISIAN BILATERAL RELATIONS: A CRITICAL STUDY ON THE ROLE OF IDEOLOGY Submitted by Almabruk Khalifa Kirfaa to the University of Exeter As a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics In December 2014 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: Almabruk Kirfaa………………………………………………………….. i Abstract Libyan-Tunisian bilateral relations take place in a context shaped by particular historical factors in the Maghreb over the past two centuries. Various elements and factors continue to define the limitations and opportunities present for regimes and governments to pursue hostile or negative policies concerning their immediate neighbours. The period between 1969 and 2010 provides a rich area for the exploration of inter-state relations between Libya and Tunisia during the 20th century and in the first decade of the 21st century. Ideologies such as Arabism, socialism, Third Worldism, liberalism and nationalism, dominated the Cold War era, which saw two opposing camps: the capitalist West versus the communist East. Arab states were caught in the middle, and many identified with one side over the other. generating ideological rivalries in the Middle East and North Africa. The anti-imperialist sentiments dominating Arab regimes and their citizens led many statesmen and politicians to wage ideological struggles against their former colonial masters and even neighbouring states. -

GRASPE Groupe De Réflexion Sur L’Avenir Du Service Public Européen Reflection Group on the Future of the European Civil Service

GRASPE Groupe de Réflexion sur l’avenir du Service Public Européen Reflection Group on the Future of the European Civil Service Cahier n° 37 Décembre 2019 Sommaire Editorial : Commission von der Leyen 3 Quelle Commission pour une Europe-puissance ? Quels moyens pour une "Union plus ambitieuse" ? The Geography of EU discontent with Lewis Dijkstra 19 La Politique européenne de voisinage en échec ? 23 Un budget pour l’Europe 2021-27 avec G-J Koopman et P. 33 Defraigne L’Union Européenne : où en sommes-nous ? Quel avenir? 41 De F. Frutuoso de Melo Dialogue avec P. Collowald 47 Conférence de J.-L. Demarty 71 Conférence : Vers une économie zéro carbone : politique 93 européenne et contributions nationales. The Backstop, What Next For Ireland? With Brian Carty 125 Exodus, Reckoning, Sacrifice: Three Meanings of Brexit, 133 par Kalypso Nicolaïdis Changer l’état des choses est aisé, l’améliorer est très difficile ERASME Diffusion strictement limitée aux personnels des Institutions européennes Groupe de réflexion sur l’avenir du service public Européen Éditeur responsable : Georges VLANDAS Rédaction : Tomas GARCIA AZCARATE, Olivier BODIN, Tremeur DENIGOT, Andréa MAIRATE, Paolo PONZANO, Kim SLAMA, Bertrand SORET, Jean-Paul SOYER, Catherine VIEILLEDENT, Sylvie VLANDAS. Site web et maquette : Jean-Paul SOYER Diffusion : Agim ISLAMAJ Société éditrice : GRAACE AISBL 23 rue du Cardinal, 1210 Bruxelles, Belgique. © GRASPE 2019 Contributeurs et personnes ayant participé aux travaux du GRASPE Envoyez vos réactions et contributions à : [email protected] -

The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason Timothy Scott Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN THE FRENCH-ALGERIAN WAR (1954-1962): HISTORICAL ANALOGY AND THE LIMITS OF FRENCH HISTORICAL REASON By Timothy Scott Johnson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 TIMOTHY SCOTT JOHNSON All Rights Reserved ii The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason by Timothy Scott Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Richard Wolin, Distinguished Professor of History, The Graduate Center, CUNY _______________________ _______________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ -

The London School of Economics and Political Science

The London School of Economics and Political Science The State as a Standard of Civilisation: Assembling the Modern State in Lebanon and Syria, 1800-1944 Andrew Delatolla A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2017 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledge is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe on the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 101,793 words. 2 Acknowledgements This PhD has been much more than an academic learning experience, it has been a life experience and period of self-discovery. None of it would have been possible without the help and support from an amazing network of family, colleagues, and friends. First and foremost, a big thank you to the most caring, attentive, and conscientious supervisor one could hope for, Dr. Katerina Dalacoura. Her help, guidance, and critiques from the first draft chapter to the final drafts of the thesis have always been a source of clarity when there was too much clouding my thoughts. -

The 1958 Good Offices Mission and Its Implications for French-American Relations Under the Fourth Republic

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1970 The 1958 Good Offices Mission and Its Implications for French-American Relations Under the Fourth Republic Lorin James Anderson Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Anderson, Lorin James, "The 1958 Good Offices Mission and Its Implications forr F ench-American Relations Under the Fourth Republic" (1970). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1468. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1467 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THBSIS Ol~ Lorin J'ames Anderson for the Master of Arts in History presented November 30, 1970. Title: The 1958 Good Offices Mission and its Implica tions for French-American Relations Under the Fourth Hepublic. APPROVED BY MEHllERS O~' THE THESIS CO.MNITTEE: Bernard Burke In both a general review of Franco-American re lations and in a more specific discussion of the Anglo American good offices mission to France in 1958, this thesis has attempted first, to analyze the foreign policies of France and the Uni.ted sta.tes which devel oped from the impact of the Second World Wa.r and, second, to describe Franco-American discord as primar ily a collision of foreign policy goals--or, even farther, as a basic collision in the national attitudes that shaped those goals--rather than as a result either of Communist harassment or of the clash of personalities.