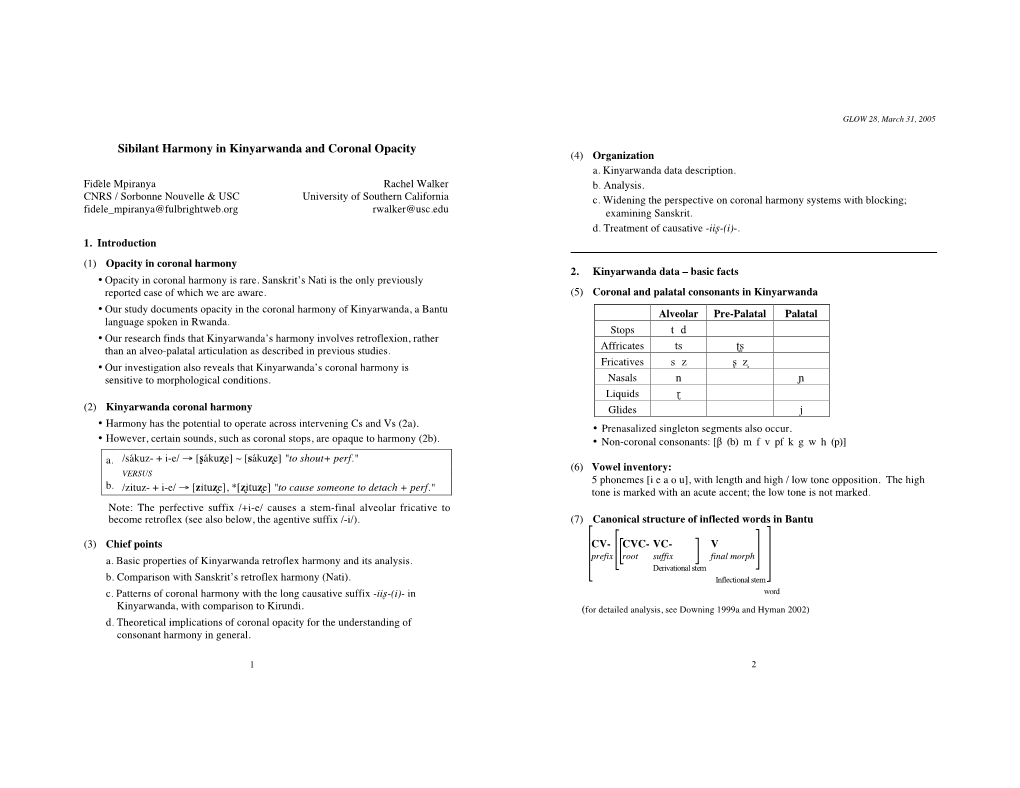

Sibilant Harmony in Kinyarwanda and Coronal Opacity (4) Organization A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Missionary /World Christianity Bibles In

Guide to Missionary / World Christianity Bibles in the Yale Divinity Library Cataloged Collection The Divinity Library holds hundreds of Bibles and scripture portions that were translated and published by missionaries or prepared by church bodies throughout the world. Dating from the eighteenth century to the present day, these Bibles and scripture portions are currently divided between the historical Missionary Bible Collection held in Special Collections and the Library's regular cataloged collection. At this time it is necessary to search both the Guide to the Missionary / World Christianity Bible Collection and the online catalog to check on the availability of works in specific languages. Please note that this listing of Bibles cataloged in Orbis is not intended to be complete and comprehensive but rather seeks to provide a glimpse of available resources. Afroasiatic (Other) Bible. New Testament. Mbuko. 2010. o Title: Aban 'am wiya awan. Bible. New Testament. Hdi. 2013. o Title: Deftera lfida dzratawi = Le Nouveau Testament en langue hdi. Bible. New Testament. Merey. 2012. o Title: Dzam Wedeye : merey meq = Le Nouveau Testament en langue merey. Bible. N.T. Gidar. 1985. o Title: Halabara meleketeni. Bible. N.T. Mark. Kera. 1988. o Title: Kel pesan ge minti Markə jirini = L'évangile selon Marc en langue kera. Bible. N.T. Limba. o Title:Lahiri banama ka masala in bathulun wo, Yisos Kraist. Bible. New Testament. Muyang. 2013. o Title: Ma mu̳weni sulumani ge melefit = Le Nouveau Testament en langue Muyang. Bible. N.T. Mark. Muyang. 2005. o Title: Ma mʉweni sulumani ya Mark abəki ni. Bible. N.T. Southern Mofu. -

The Whistled Fricatives of Southern Bantu

Just put your lips together and blow? The whistled fricatives of Southern Bantu Ryan K. Shosted12∗ 1Dept of Linguistics, University of California, Berkeley 1203 Dwinelle Hall #2650 – Berkeley, CA 94120-2650 USA 2Dept of Linguistics, University of California, San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive #108 – La Jolla, CA 92093-0108 USA [email protected] Abstract. Phonemically, whistled fricatives /s z / are rare, limited almost en- Ţ Ţ tirely to Southern Bantu. Reports differ as to whether they are realized with labial protrusion and/or rounding. Phonetically, whistled sibilants are com- mon; they are regarded as a feature of disordered speech in English. According to the clinical literature, unwanted whistled fricatives are triggered by dental prosthesis and/or orthodontics that alter the geometry of the incisors—not by aberrant lip rounding. Based on aeroacoustic models of various types of whis- tle supplemented with acoustic data from the Southern Bantu language Tshwa (S51), this paper contends that labiality is not necessary for the production of whistled fricatives. 1. Introduction 1.1. Typology Few phonemes are as typologically restricted as the so-called whistled, whistling, or whistly fricatives / s z /.1 They are said to occur in only a handful of languages: the Shona Ţ Ţ (S10) and Tshwa-Ronga (S50) groups of Southern Bantu (Bladon et al., 1987; Sitoe, ∗This research was supported by a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship and a Fulbright Fellowship to the author. I would like to thank John Ohala, Keith Johnson, and Ian Maddieson for their insights. I am also grateful to Larry Hyman for his help with the diachronic data. -

The Violability of Backness in Retroflex Consonants

The violability of backness in retroflex consonants Paul Boersma University of Amsterdam Silke Hamann ZAS Berlin February 11, 2005 Abstract This paper addresses remarks made by Flemming (2003) to the effect that his analysis of the interaction between retroflexion and vowel backness is superior to that of Hamann (2003b). While Hamann maintained that retroflex articulations are always back, Flemming adduces phonological as well as phonetic evidence to prove that retroflex consonants can be non-back and even front (i.e. palatalised). The present paper, however, shows that the phonetic evidence fails under closer scrutiny. A closer consideration of the phonological evidence shows, by making a principled distinction between articulatory and perceptual drives, that a reanalysis of Flemming’s data in terms of unviolated retroflex backness is not only possible but also simpler with respect to the number of language-specific stipulations. 1 Introduction This paper is a reply to Flemming’s article “The relationship between coronal place and vowel backness” in Phonology 20.3 (2003). In a footnote (p. 342), Flemming states that “a key difference from the present proposal is that Hamann (2003b) employs inviolable articulatory constraints, whereas it is a central thesis of this paper that the constraints relating coronal place to tongue-body backness are violable”. The only such constraint that is violable for Flemming but inviolable for Hamann is the constraint that requires retroflex coronals to be articulated with a back tongue body. Flemming expresses this as the violable constraint RETRO!BACK, or RETRO!BACKCLO if it only requires that the closing phase of a retroflex consonant be articulated with a back tongue body. -

African Dialects

African Dialects • Adangme (Ghana ) • Afrikaans (Southern Africa ) • Akan: Asante (Ashanti) dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Fante dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Twi (Akwapem) dialect (Ghana ) • Amharic (Amarigna; Amarinya) (Ethiopia ) • Awing (Cameroon ) • Bakuba (Busoong, Kuba, Bushong) (Congo ) • Bambara (Mali; Senegal; Burkina ) • Bamoun (Cameroons ) • Bargu (Bariba) (Benin; Nigeria; Togo ) • Bassa (Gbasa) (Liberia ) • ici-Bemba (Wemba) (Congo; Zambia ) • Berba (Benin ) • Bihari: Mauritian Bhojpuri dialect - Latin Script (Mauritius ) • Bobo (Bwamou) (Burkina ) • Bulu (Boulou) (Cameroons ) • Chirpon-Lete-Anum (Cherepong; Guan) (Ghana ) • Ciokwe (Chokwe) (Angola; Congo ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Mauritian dialect (Mauritius ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Seychelles dialect (Kreol) (Seychelles ) • Dagbani (Dagbane; Dagomba) (Ghana; Togo ) • Diola (Jola) (Upper West Africa ) • Diola (Jola): Fogny (Jóola Fóoñi) dialect (The Gambia; Guinea; Senegal ) • Duala (Douala) (Cameroons ) • Dyula (Jula) (Burkina ) • Efik (Nigeria ) • Ekoi: Ejagham dialect (Cameroons; Nigeria ) • Ewe (Benin; Ghana; Togo ) • Ewe: Ge (Mina) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewe: Watyi (Ouatchi, Waci) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewondo (Cameroons ) • Fang (Equitorial Guinea ) • Fõ (Fon; Dahoméen) (Benin ) • Frafra (Ghana ) • Ful (Fula; Fulani; Fulfulde; Peul; Toucouleur) (West Africa ) • Ful: Torado dialect (Senegal ) • Gã: Accra dialect (Ghana; Togo ) • Gambai (Ngambai; Ngambaye) (Chad ) • olu-Ganda (Luganda) (Uganda ) • Gbaya (Baya) (Central African Republic; Cameroons; Congo ) • Gben (Ben) (Togo -

Presentation Overview Course Objectives What Is a Sibilant A

1 The Entire World Presentation Overview of Sibilants™ • Targeted for intermediate level of knowledge. However, encompass entry- level to experienced clinicians. • Review S & Z first, then SH & CH, J, ZH. • Evaluation procedure. Christine Ristuccia, M.S. CCC-SLP • Specific treatment strategies. www.sayitright.org • Case study examples. ©2007 Say It Right ©2007 Say It Right Course Objectives What is a Sibilant • Know how to evaluate and treat the various word positions of the sibilant sounds:[s, z, ch, sh, sh, j, and zh]. A consonant characterized • Know how to use co-articulation to elicit correct tongue positioning. by a hissing sound. • Be able to write measurable and objective IEP goals. • Be able to identify 3 elicitation techniques S, Z,Z, SH, ZH, CH, and J • Identify natural tongue positioning for /t/, /n/, /l/ and /d/. • Know difference between frontal and lateral lisp disorders. ©2007 Say It Right ©2007 Say It Right Facts About /s/ & /z/ Facts About [s] & [z] • Cognates. Have same manner and [s] spellings S as in soup production with the exception of C as in city voicing. Sc as in science X as in box • Airflow restricted or released by tongue causes production and common “hissing” sound. [z] spellings s as in pans x as in xylophone • Different spellings, same production. z as in zoo ©2007 Say It Right ©2007 Say It Right Say It Right™ • 888—811-0759 • [email protected] • www.sayitright.org ©2007 Say It Right™ All rights reserved. 2 Two Types of Lisp Frontal Lisp Disorders • Most common Frontal Lateral • Also called interdental lisp • Trademark sound - /th/ • Cause: Tongue is protruding too far forward. -

Legends for Videos

Case-Based Learning through Videos: A Virtual Walk through Our Clinic From Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Anomalies: The Effects on Speech and Resonance, 3rd Edition Ann W. Kummer, Ph.D., CCC-SLP Most students and professionals in speech-language pathology learn about communication disorders from reading textbooks first, and then by attending lectures. This type of learning is not only required for the degree, but is also essential in order to obtain basic and theoretical information for clinical practice. Unfortunately, book knowledge alone does not adequately prepare the learner to evaluate and treat individuals affected by communication disorders. As such, the American Speech-Language- Hearing Association (ASHA) has observation requirements for graduation in speech-language pathology (or communication sciences and disorders) at the bachelor’s level, and practicum experience requirements for graduation at the master’s level. In addition, it is universally recognized that observing, interacting, problem-solving, and obtaining experience in real-life clinical situations is essential for individuals to be able to apply learned didactic information appropriately and effectively in clinical situations. Although observation and practicum experiences are essential for clinical learning, there are many issues and inefficiencies when trying to obtain these experiences. First, students (and professionals wanting to obtain additional competencies) usually need to schedule the experience with an outside facility, and then travel to the location. There is a risk that the patient will cancel or be a no-show. There is also the possibility that the session is not a good one for various reasons. The experience may not be focused learning. For example, the student/observer may understand the point of the session in 5 minutes, but need to be present for the entire session, which can take an hour or more. -

Bantu Plant Names As Indicators of Linguistic Stratigraphy in the Western Province of Zambia

Bantu Plant Names as Indicators of Linguistic Stratigraphy in the Western Province of Zambia Koen Bostoen Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren - Université libre de Bruxelles 1. Introduction and background The present paper is a comparative study of Bantu plant names in a number of languages from the WP of Zambia.1 It is based on fieldwork I undertook, with the kind assistance of the Livingstone Museum, in July-August 2005 in the neighbourhood of two minor towns in the southern part of the WP, i.e. Sioma and Shangombo. I worked with native speakers of Mbunda (K15), Kwamashi (K34), Kwamulonga (K351), Shanjo (K36), Fwe (K402), and Mbwera (L61). The field notes, which I present throughout the paper with the label “Bostoen FN 2005”, are compared to data from closely related or neighbouring languages on the one hand, and on the other hand, to what is known on plant names in terms of common Bantu reconstructions. Map 1 below shows the Bantu languages considered in this paper and their linguistic affiliation according to the current state of knowledge. Data from Khwe, a nearby non-Bantu click language from the Khoe-Kwadi family (Güldemann 2004), are also taken into account for reasons explained further on. 2 This comparative study aims at enhancing our understanding of the language history, which underlies the intricate sociolinguistic picture that characterizes the WP today. The Bantu languages listed above represent only a fraction of the numerous languages to which the WP is home. Contrary to Lozi (K21), the region’s widely used lingua franca with an increasing number of first language speakers, most of these languages are minority languages whose use is geographically localized and functionally restricted and whose number of speakers is declining. -

Aerodynamic Constraints on Sound Change: the Case of Syllabic Sibilants

AERODYNAMIC CONSTRAINTS ON SOUND CHANGE: THE CASE OF SYLLABIC SIBILANTS Alan C. L. Yu University of California, Berkeley, USA ABSTRACT pressure buildup behind the constriction of a fricative is High vowels are known to assimilate in place of articulation severely diminished, resulting in no audible turbulence. and frication to a preceding sibilant. Such an assimilation This paper begins with a brief discussion on the basic facts process is found in a historical sound change from Middle about syllabic sibilants. In section 3, an investigation of the Chinese to Modern Mandarin (e.g., */si/ became [sz]` 'poetry'). aerodynamic properties of oral vowels, vowels before a nasal However, such assibilation is systematically absent when the and nasalized vowels is presented. This investigation reveals vowel is followed by a nasal consonant. This paper investigates that the anticipatory velic opening during the production of a the co-occurrence restriction between nasalization and vowel before a nasal bleeds the pharyngeal pressure build-up. frication, demonstrating that when pharyngeal pressure is Based on this, a physical explanation of the non-fricativizing vented significantly during the opening of the velic valve, the property of vowel before nasal is advanced. necessary pressure buildup behind the constriction of a fricative is severely diminished, resulting in no audible turbulence. It 2. SYLLABIC SIBILANTS? reports the aerodynamic effects of nasalization on vowels, as 2.1. Some facts about syllabic sibilants spoken by a native speaker of American English (presumed to Syllabic sibilants are generally rather uncommon among the parallel the phonetic conditions present in Middle Chinese). world's language. Bell [2] reports in his survey that of the 182 The results reveal that in comparison to oral vowels the languages of major language families and areas of the world 85 pharyngeal pressure, volume velocity and particle velocity of them possess syllabic consonants while only 24 of them decrease dramatically when high vowels are nasalized. -

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE. The Court strongly prefers to use live interpreters in the courtrooms whenever possible. However, when the Court can’t find live interpreters, we sometimes use Language Line, a national telephone service supplying interpreters for most languages on the planet almost immediately. The number for that service is 1-800-874-9426. Contact Circuit Administration at 605-367-5920 for the Court’s account number and authorization codes. AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE/DEAF INTERPRETATION Minnehaha County in the 2nd Judicial Circuit uses a combination of local, highly credentialed ASL/Deaf interpretation providers including Communication Services for the Deaf (CSD), Interpreter Services Inc. (ISI), and highly qualified freelancers for the courts in Sioux Falls, Minnehaha County, and Canton, Lincoln County. We are also happy to make court video units available to any other courts to access these interpreters from Sioux Falls (although many providers have their own video units now). The State of South Dakota has also adopted certification requirements for ASL/deaf interpretation “in a legal setting” in 2006. The following link published by the State Department of Human Services/ Division of Rehabilitative Services lists all the certified interpreters in South Dakota and their certification levels, and provides a lot of other information on deaf interpretation requirements and services in South Dakota. DHS Deaf Services AFRICAN DIALECTS A number of the residents of the 2nd Judicial Circuit speak relatively obscure African dialects. For court staff, attorneys, and the public, this list may be of some assistance in confirming the spelling and country of origin of some of those rare African dialects. -

Sibilant Production in Hebrew-Speaking Adults: Apical Versus Laminal

Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics ISSN: 0269-9206 (Print) 1464-5076 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/iclp20 Sibilant production in Hebrew-speaking adults: Apical versus laminal Michal Icht & Boaz M. Ben-David To cite this article: Michal Icht & Boaz M. Ben-David (2017): Sibilant production in Hebrew- speaking adults: Apical versus laminal, Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699206.2017.1335780 View supplementary material Published online: 20 Jul 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=iclp20 Download by: [109.64.26.236] Date: 20 July 2017, At: 21:54 CLINICAL LINGUISTICS & PHONETICS https://doi.org/10.1080/02699206.2017.1335780 Sibilant production in Hebrew-speaking adults: Apical versus laminal Michal Ichta and Boaz M. Ben-Davidb,c,d aCommunication Disorders Department, Ariel University, Ariel, Israel; bCommunication, Aging and Neuropsychology Lab (CANlab), Baruch Ivcher School of Psychology, Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya, Herzliya, Israel; cDepartment of Speech-Language Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; dToronto Rehabilitation Institute, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The Hebrew IPA charts describe the sibilants /s, z/ as ‘alveolar fricatives’, Received 1 December 2016 where the place of articulation on the palate is the alveolar ridge. The Revised 22 May 2017 point of constriction on the tongue is not defined – apical (tip) or laminal Accepted 24 May 2017 (blade). Usually, speech and language pathologists (SLPs) use the apical KEYWORDS placement in Hebrew articulation therapy. -

Spectral Measures for Sibilant Fricatives of English, Japanese, and Mandarin Chinese

SPECTRAL MEASURES FOR SIBILANT FRICATIVES OF ENGLISH, JAPANESE, AND MANDARIN CHINESE Fangfang Li a, Jan Edwards b, & Mary Beckman a aDepartment of Linguistics, OSU & bDepartment of Communicative Disorders, UW {cathy|mbeckman}@ling.ohio-state.edu, [email protected] ABSTRACT English /s/ and / Ѐ/ can be differentiated by the Most acoustic studies of sibilant fricatives focus on spectral properties of the frication itself [1, 8]. As languages that have a place distinction like the mentioned earlier, English /s/ and / Ѐ/ contrast in English distinction between coronal alveolar /s/ place, with the narrowest lingual constriction being and coronal post-alveolar / Ѐ/. Much less attention made more backward in the oral cavity for / Ѐ/ than has been paid to languages such as Japanese, for /s/. The longer front cavity in producing / Ѐ/ where the contrast involves tongue posture as lowers the overall frequency for the major energy much as position. That is, the Japanese sibilant that concentration in the fricative spectrum. The length an alveolopalatal fricative difference is further enhanced by lip protrusion in ,/נ / contrasts with /s/ is that has a “palatalized” tongue shape (a bunched /Ѐ/, so that it has been consistently observed that predorsum). This paper describes measures that there is more low-frequency energy for the / Ѐ/ can be calculated from the fricative interval alone, spectrum and more high-frequency energy for /s/ which we applied both to the place distinction of [8, 16]. English and the “palatalization” or posture This generalization about a difference in energy distinction of Japanese. The measures were further tested on Mandarin Chinese, a language that has a distribution between /s/ and / Ѐ/ can be captured three-way contrast in sibilant fricatives contrasting effectively by the centroid frequency, the first in both tongue position and posture. -

Pots, Words and the Bantu Problem: on Lexical Reconstruction and Early African History*

Journal of African History, 48 (2007), pp. 173–99. f 2007 Cambridge University Press 173 doi:10.1017/S002185370700254X Printed in the United Kingdom POTS, WORDS AND THE BANTU PROBLEM: ON LEXICAL RECONSTRUCTION AND EARLY AFRICAN HISTORY* BY KOEN BOSTOEN Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren, Universite´ libre de Bruxelles ABSTRACT: Historical-comparative linguistics has played a key role in the recon- struction of early history in Africa. Regarding the ‘Bantu Problem’ in particular, linguistic research, particularly language classification, has oriented historical study and been a guiding principle for both historians and archaeologists. Some historians have also embraced the comparison of cultural vocabularies as a core method for reconstructing African history. This paper evaluates the merits and limits of this latter methodology by analysing Bantu pottery vocabulary. Challenging earlier interpretations, it argues that speakers of Proto-Bantu in- herited the craft of pot-making from their Benue-Congo-speaking ancestors who introduced this technology into the Grassfields region. This ‘Proto-Bantu ceramic tradition’ was the result of a long, local development, but spread quite rapidly into Atlantic Central Africa, and possibly as far as Southern Angola and northern Namibia. The people who brought Early Iron Age (EIA) ceramics to southwestern Africa were not the first Bantu-speakers in this area nor did they introduce the technology of pot-making. KEY WORDS: Archaeology, Bantu origins, linguistics. T HE Bantu languages stretch out from Cameroon in the west to southern Somalia in the east and as far as Southern Africa in the south.1 This group of closely related languages is by far Africa’s most widespread language group.