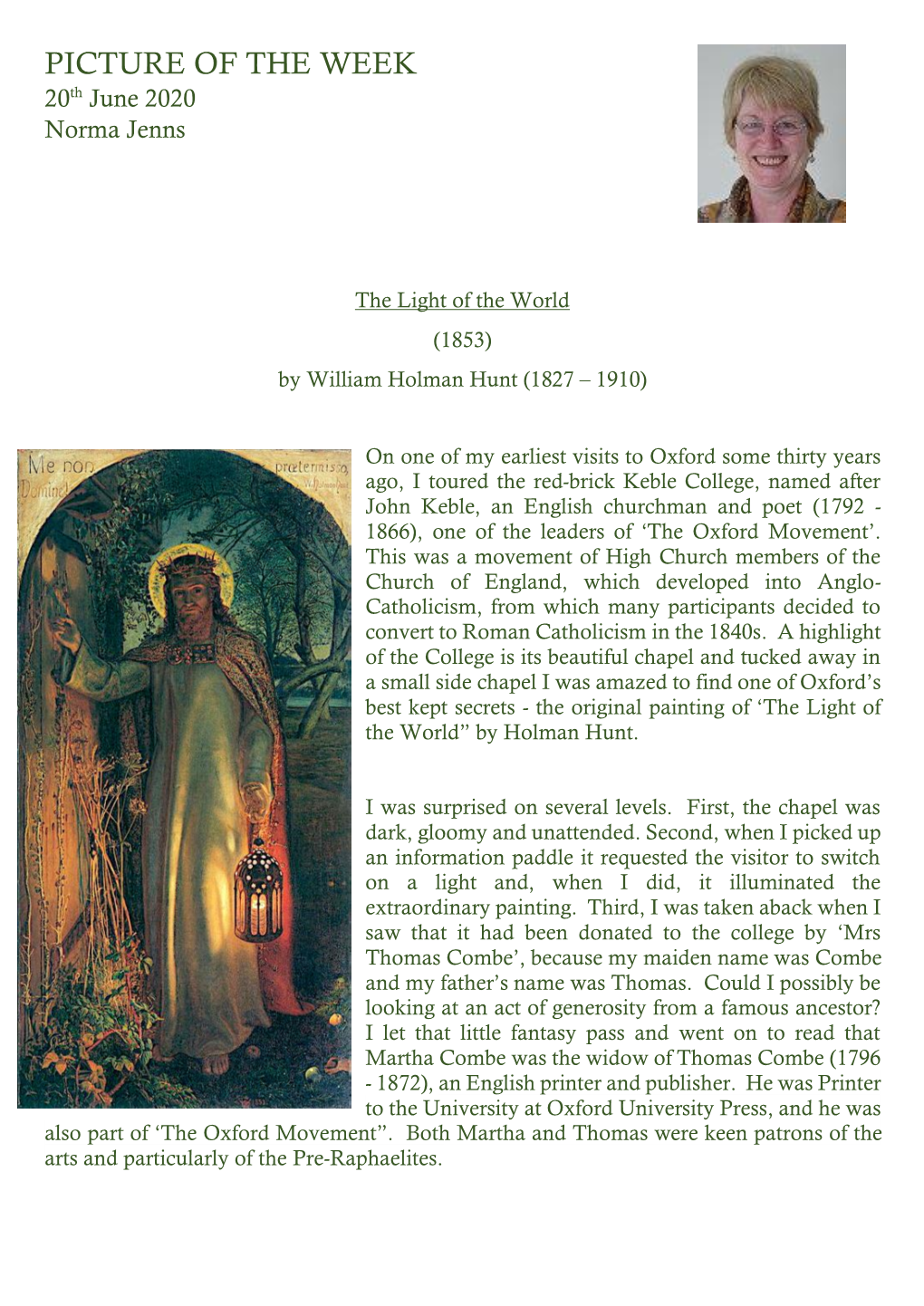

20Th June 2020 Norma Jenns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Afterglow in Egypt Teachers' Notes

Teacher guidance notes The Afterglow in Egypt 1861 A zoomable image of this painting is available by William Holman Hunt on our website to use in the classroom on an interactive whiteboard or projector oil on canvas 82 x 37cm www.ashmolean.org/learning-resources These guidance notes are designed to help you use paintings from our collection as a focus for cross- curricular teaching and learning. A visit to the Ashmolean Museum to see the painting offers your class the perfect ‘learning outside the classroom’ opportunity. Starting questions Questions like these may be useful as a starting point for developing speaking and listening skills with your class. What catches your eye first? What is the lady carrying? Can you describe what she is wearing? What animals can you see? Where do you think the lady is going? What do you think the man doing? Which country do you think this could be? What time of day do you think it is? Why do you think that? If you could step into the painting what would would you feel/smell/hear...? Background Information Ideas for creative planning across the KS1 & 2 curriculum The painting You can use this painting as the starting point for developing pupils critical and creative thinking as well as their Hunt painted two verions of ‘The Afterglow in Egypt’. The first is a life-size painting of a woman learning across the curriculum. You may want to consider possible ‘lines of enquiry’ as a first step in your cross- carrying a sheaf of wheat on her head, which hangs in Southampton Art Gallery. -

St Barnabas and St Paul, with St Thomas the Martyr Parish Profile

September 2018 St Barnabas and St Paul, with St Thomas the Martyr Parish profile Unity and Mutual Respect United, friendly and welcoming – we hope that is the impression our congregation might Why I worship here: make on a first-time visitor to our principal service, the 10.30am Sunday High Mass at St Traditional liturgy with Barnabas. Ours is not a predominantly elderly congregation: we have young families as well its timeless beauty and as people who have worshipped here for many decades, and everything in between. holiness. Originally worshippers came predominantly from the parish itself, then an industrial suburb; now they come from all over Oxford and beyond – indeed, all over the world – drawn by our Tractarian heritage, with its beautiful liturgy, excellent music, and sound but concise sermons. The congregation also reflects Oxford’s place in the wider world; many nationalities and backgrounds are represented, pointing to the profound truth that we are one Contents: in Christ. Unity and Mutual Respect Our New Incumbent History Liturgy and Worship Music Church Life Parish Links About the Parish Vicarage Properties Challenges and Opportunities From the Bishop The Oxford Deanery This fellowship is also expressed socially. The newly-installed kitchen/servery at the west Appendices: end of the church not only encourages a lively coffee-time after Mass but enables us to Summary Accounts 2017 gather for Lent courses and study days over a shared lunch and to celebrate feast days in some style. Motion & Statement of Need Map of Parish Throughout this profile the reader will find occasional statements headed ‘Why I worship here’. -

PRE-RAPHAELITES: DRAWINGS and WATERCOLOURS Opening Spring 2021, (Dates to Be Announced)

PRESS RELEASE 5 February 2021 for immediate release: PRE-RAPHAELITES: DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS Opening Spring 2021, (dates to be announced) Following the dramatic events of 2020 and significant re-scheduling of exhibition programmes, the Ashmolean is delighted to announce a new exhibition for spring 2021: Pre-Raphaelites: Drawings and Watercolours. With international loans prevented by safety and travel restrictions, the Ashmolean is hugely privileged to be able to draw on its superlative permanent collections. Few people have examined the large number of Pre-Raphaelite works on paper held in the Western Art Print Room. Even enthusiasts and scholars have rarely looked at more than a selection. This exhibition makes it possible to see a wide range of these fragile works together for the first time. They offer an intimate and rare glimpse into the world of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the artists associated with the movement. The exhibition includes works of extraordinary beauty, from the portraits they made of each other, studies for paintings and commissions, to subjects taken from history, literature and landscape. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) In 1848 seven young artists, including John Everett Millais, William The Day Dream, 1872–8 Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, resolved to rebel against the Pastel and black chalk on tinted paper, 104.8 academic teaching of the Royal Academy of Arts. They proposed a × 76.8 cm Ashmolean Museum. University of Oxford new mode of working, forward-looking despite the movement’s name, which would depart from the ‘mannered’ style of artists who came after Raphael. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) set out to paint with originality and authenticity by studying nature, celebrating their friends and heroes and taking inspiration from the art and poetry about which they were passionate. -

Week of Wall-To-Wall Art

No. 70, May 2011 Published by the Jericho Community Association – www.jerichocentre.org.uk Week of wall-to-wall art Hub of Artweeks action Twelve-year-old ericho has become a major centre of Lucien Ohanian JOxfordshire Artweeks, which this of Shirley Place, year will run in Jericho from May 21-30. alongside some Oxford’s was the first Artweeks in the of his abstract photography. His country, and it is still by far the largest. unusual image According to one of Jericho’s promi- of a wine bottle nent artists, Valerie Petts of Cardigan was used for the Street, “Artweeks is such an amazing or- cover of last year’s ganization. With so many venues it has Artweeks poster and become much more of a festival. It’s not catalogue. Other about big commercial things. Anybody in young artists will the community is free to put their work be exhibiting their up. And people need not feel intimidated work at St Barnabas about visiting all these places and look- School. ing at art.” Jericho has long been a centre for art- twoartstudiosonthetopfloorforsome death. After they ran into heavy opposition ists, with neighbours working away in years. But we now also have the Art Jeri- from the press in London they retreated to vastly contrasting styles. Those in Great cho gallery in King Street. And many lo- Oxford,specificallytoJerichowherethey Clarendon Street, for example, range cal cafés will have exhibitions. Footsore found a patron in Thomas Combe, the su- from David Langford’s traditional scenes art enthusiasts can also get a cup of tea at perintendent of the Clarendon Press who of Oxford to Lulu Wong Taylor’s dramatic St. -

William Holman Hunt's Portrait of Henry Wentworth Monk

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 William Holman Hunt’s Portrait of Henry Wentworth Monk Jennie Mae Runnels Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4920 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. William Holman Hunt’s Portrait of Henry Wentworth Monk A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History at Virginia Commonwealth University. Jennie Runnels Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Art History MA Thesis Spring 2017 Director: Catherine Roach Assistant Professor Department of Art History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia April 2017 Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Chapter 1 Holman Hunt and Henry Monk: A Chance Meeting Chapter 2 Jan van Eyck: Rediscovery and Celebrity Chapter 3 Signs, Symbols and Text Conclusion List of Images Selected Bibliography Acknowledgements In writing this thesis I have benefitted from numerous individuals who have been generous with their time and encouragement. I owe a particular debt to Dr. Catherine Roach who was the thesis director for this project and truly a guiding force. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Eric Garberson and Dr. Kathleen Chapman who served on the panel as readers and provided valuable criticism, and Dr. Carolyn Phinizy for her insight and patience. -

Painted Sermons: Explanatory Rhetoric and William Holman Hunt’S Inscribed Frames

PAINTED SERMONS: EXPLANATORY RHETORIC AND WILLIAM HOLMAN HUNT’S INSCRIBED FRAMES Karen D. Rowe A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2005 Committee: Sue Carter, Advisor Catherine Cassara Graduate Faculty Representative Thomas Wymer Richard Gebhardt Bruce Edwards ii ABSTRACT Sue Carter, Advisor This study was undertaken to determine the rhetorical function of the verbal texts inscribed on the frames of the paintings of the Victorian Pre-Raphaelite artist William Holman Hunt. The nineteenth century expansion of the venues of rhetoric from spoken to written forms coupled with the growing interest in belle lettres created the possibility for the inscriptions to have a greater function than merely captioning the work. Visits were made to museums in the United States and Great Britain to ascertain which of Hunt’s paintings have inscribed frames. In addition, primary sources at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and the British Library, London, were consulted to determine if the artist had recorded his design plans or stated any specific purpose for the inscriptions. Contemporary reviews and exhibition catalogs were also consulted at these libraries. In addition, secondary sources were examined for relevant discussions of Hunt’s works. It was concluded that the inscribed works fit the parameters of explanatory rhetoric, a form informational and didactic rather than persuasive in nature. The common nineteenth century venue for explanatory rhetoric was the pulpit, instructing converted parishioners about Church doctrines and their Christian duties. It was also concluded that this shift in rhetorical purpose was not new to the Victorian era, rather that there is a long history of explanatory rhetoric going back at least to Augustine. -

St Barnabas and St Paul, with St Thomas the Martyr Parish Profile

September 2018 St Barnabas and St Paul, with St Thomas the Martyr Parish profile Unity and Mutual Respect United, friendly and welcoming – we hope that is the impression our congregation might Why I worship here: make on a first-time visitor to our principal service, the 10.30am Sunday High Mass at St Traditional liturgy with Barnabas. Ours is not a predominantly elderly congregation: we have young families as well its timeless beauty and as people who have worshipped here for many decades, and everything in between. holiness. Originally worshippers came predominantly from the parish itself, then an industrial suburb; now they come from all over Oxford and beyond – indeed, all over the world – drawn by our Tractarian heritage, with its beautiful liturgy, excellent music, and sound but concise sermons. The congregation also reflects Oxford’s place in the wider world; many nationalities and backgrounds are represented, pointing to the profound truth that we are one Contents: in Christ. Unity and Mutual Respect Our New Incumbent History Liturgy and Worship Music Church Life Parish Links About the Parish Vicarage Properties Challenges and Opportunities From the Bishop The Oxford Deanery This fellowship is also expressed socially. The newly-installed kitchen/servery at the west Appendices: end of the church not only encourages a lively coffee-time after Mass but enables us to Summary Accounts 2017 gather for Lent courses and study days over a shared lunch and to celebrate feast days in some style. Motion & Statement of Need Map of Parish Throughout this profile the reader will find occasional statements headed ‘Why I worship here’. -

Jericho Conservation Area Designation Study

Jericho Conservation Area Designation Study Oxford City Council – City Development October 2010 Contents Reason for the Study........................................................................................3 Study Area........................................................................................................4 Summary of Significance..................................................................................5 Vulnerability......................................................................................................7 Opportunity for Enhancement ..........................................................................9 Archaeological Interest...................................................................................10 Designated Heritage Assets and Buildings of Local Architectural and Historic Interest............................................................................................................12 Designated Heritage Assets in the surrounding area that influence the character of the study area:............................................................................12 Historic Development .....................................................................................14 Medieval 1086 – 1453 ................................................................................14 Early Modern 1453-1789 ............................................................................16 1790-1899...................................................................................................19 -

Jericho and the Pre-Raphaelites

1 Jericho and the Pre-Raphaelites John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shallot The past is not dead, it is living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make. William Morris Few people are aware that the area of Oxford known as Jericho has a number of striking connections with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood which, as well as being the only British art movement to take on international significance, has claims to being the best-loved art movement of all. The Pre-Raphaelites' patron Thomas Combe, in company with his wife Martha, presided over what became a kind of "good-humoured salon" [Jon Whiteley, 'Oxford and the Pre-Raphaelites', Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1989, p. 26] in Jericho at the Combe's residence in Walton Street and the existence of this Jericho base led to the creation of a series of memorable paintings which were first of all painted, then hung and exhibited in Jericho. In 1850 Combe, who was then printer to the university, came across John Everett 2 Millais in Botley Wood where, together with Charles Collins - Wilkie's brother - he was engaged in painting. Combe took an interest in what they were both doing and invited them back to Jericho for lunch. Millais and Collins declined the invitation on the grounds that they were too busy. However, undeterred, Combe sent them over a hamper of food on his return and this was how the relationship began - one which would establish Jericho as a stamping-ground for Collins and Millais, later to be followed by other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. -

The Evolution of the Ashmolean Natural History Society 1880-1901 M

The evolution of the Ashmolean Natural History Society 1880-1901 M. Price Summary In 1880, a new scientific society, the Oxfordshire Natural History and Field Club was formed in Oxford. In 1901 this Society was amalgamated, for expedient reasons, with an Oxford University based society, The Ashmolean Society, founded in 1828. In 1901 the two societies were integrated and re-named, to become the current Ashmolean Natural History Society of Oxfordshire. Introduction This article will focus on the background of the formation of the Oxfordshire Natural History and Field Club between 1880 and 1901 and the diverse nature of the people who were involved with its activities throughout its independent existence. It begins with an overview of the gradual changes taking place in the social and intellectual climate of mid-nineteenth-century Oxford. This will be followed by a brief account of the academic climate in Oxford and the nature of the ‘town and gown’ divide within its local societies. A prosopography of various individuals mentioned in the text will be found in Appendix 1. Further detail can be found in Price (2007). The Ashmolean Society and the Oxford Architectural and Historical Society (formed in 1839 as the Oxford Society for the Promotion of Gothic Architecture) were predominantly for the benefit of elected University members and rarely accessible to those outside its milieu. The foundation of the Oxfordshire Natural History and Field Club was the means by which a new scientific society was able to meet the needs of many individuals in the way that existing intellectual societies did not. -

Hunt-Tupper Collection Msshm 54509-54686

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8mw2qb0 No online items Hunt-Tupper Collection mssHM 54509-54686 Suzanne Oatey The Huntington Library May 2020 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Hunt-Tupper Collection mssHM mssHM 54509-54686 1 54509-54686 Contributing Institution: The Huntington Library Title: Hunt-Tupper collection Creator: Hunt, William Holman, 1827-1910 Creator: Tupper, John Lucas, approximately 1823-1879 Identifier/Call Number: mssHM 54509-54686 Physical Description: 3.51 Linear Feet (3 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1850-1931 Abstract: A collection of correspondence chiefly between Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt and fellow artist and friend, John Lucas Tupper. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Conditions Governing Use The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. Hunt-Tupper collection, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Immediate Source of Acquisition Purchased from Sotheby's, lot 751, July 1971. Biographical / Historical William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) was an English painter who, with Sir John Everett Millais (1829-1896), originated the Pre-Raphaelite movement. He married Frances Waugh, but she died as a result of complications giving birth to their son Cyril Benone Holman Hunt. Hunt later married Frances's sister, Marion Edith Waugh, and they had two children, Gladys Mulock Holman Hunt and Hilary Holman Hunt. -

Sir John Everett Millais, Bart, PRA Ferdinand Lured by Ariel 1849

Sir John Everett Millais, Bart, P.R.A. Ferdinand Lured by Ariel 1849-1850 Oil on panel, 64.8 x 50.8 cm (arched top) Signed and dated in monogram, lower left, JEMillais / 1849 Exhibited: Royal Academy 1850, no. 504; Royal Scottish Academy 1854, no. 322; Fine Art Society, London, ‘The Collected Works of John Everett Millais’ 1881, no. 2; Grosvenor Gallery, London, ‘Exhibition of the Works of Sir John E. Millais, Bart, R.A.’ 1886, no. 78; Guildhall, London, ‘Loan Collection of Pictures by Painters of the British School who have flourished during Her Majesty’s Reign’ 1897, no. 131; Royal Academy, ‘Works by the Late Sir John Everett Millais’ 1898, no. 58; Carfax Gallery, London, ‘A Century of Art, 1810-1910’ 1911, no. 48; Tate Gallery, ‘Works by the English Pre-Raphaelite Painters Lent by the Art Gallery Committee of the Birmingham Corporation’ 1911-12, no. 14; Tate Gallery, ‘Paintings and Drawings of the 1860s Period’ 1923, no. 86; Royal Academy, ‘Exhibition of British Art c. 1000-1860’ 1934, no. 566; Birmingham City Art Gallery, ‘The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’ 1947, no. 51; Whitechapel Gallery, ‘The Pre-Raphaelites: A Loan Exhibition of their Paintings and Drawings held in the Centenary Year of the Foundation of the Brotherhood’ 1948, no. 44; Royal Academy and Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, ‘Millais P.R.B./ P.R.A.’ 1967, no. 23; King’s Lynn, ‘The Pre-Raphaelites as Painters and Draughtsmen, a Loan Exhibition from Two Private Collections’ 1971, no. 54; Tate Gallery, ‘The Pre-Raphaelites’ 1984, no. 24; Frick Collection, New York, ‘Victorian Fairy Painting’ 1998-9, ex-cat.; Yale Center for British Art and Huntingdon Library, San Marino, ‘Great British Paintings from American Collections: Holbein to Hockney’ 2001-2, no.