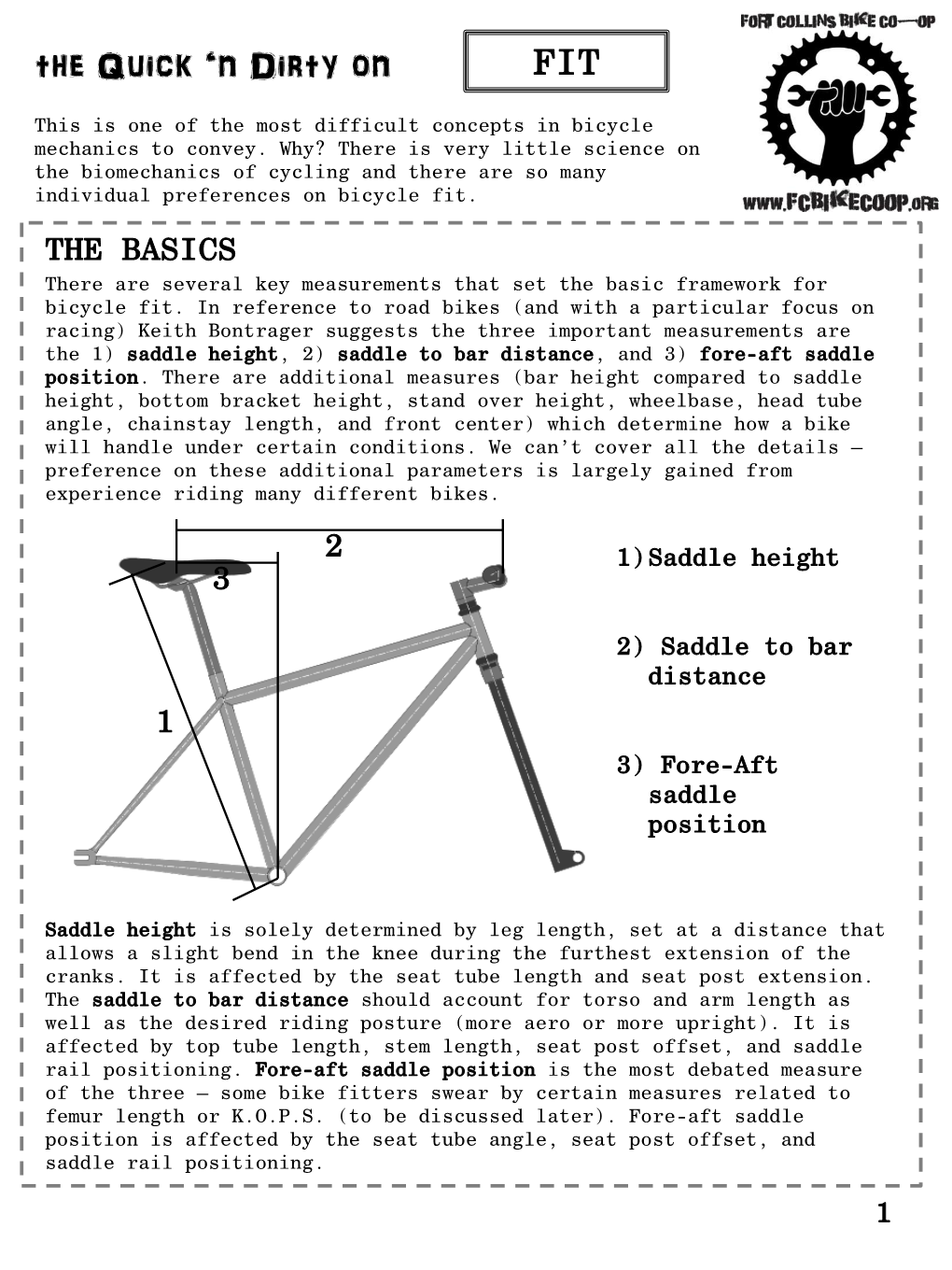

N Dirty on FIT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bakalářská Práce

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra atletiky, plavání a sport ů v p řírod ě Historie mountainbikingu Bakalá řská práce Vedoucí bakalá řské práce: Vypracoval: Mgr. Sylva H řebí čková Lukáš Hyrák SEBS Brno, 2010 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalá řskou práci vypracoval samostatn ě a na základ ě literatury a pramen ů uvedených v použitých zdrojích. V Brn ě dne 13. dubna 2010 ……………………… Děkuji sle čně Mgr. Sylv ě H řebí čkové za odborné vedení, cenné rady a pomoc p ři vypracování této bakalá řské práce. OBSAH Úvod ..............................................................................................................5 1. Mountainbiking ....................................................................................6 1. 1. Disciplíny mountainbikingu...........................................................6 1. 2. Druhy horských kol........................................................................9 2. Historie mountainbikingu ..................................................................12 2. 1. Historie cyklistiky........................................................................12 2. 2. Po čátky mountainbikingu............................................................14 2. 3. Doba pr ůkopník ů.........................................................................17 2. 4. Rozvoj mountainbikingu pro širokou veřejnost...........................23 2. 5. Zlatý v ěk mountainbikingu..........................................................27 2. 6. Úpadek závodního mountainbikingu a dopad na jeho další rozvoj.....................................................................33 -

Secondary Research – Mountain Biking Market Profiles

Secondary Research – Mountain Biking Market Profiles Final Report Reproduction in whole or in part is not permitted without the express permission of Parks Canada PAR001-1020 Prepared for: Parks Canada March 2010 www.cra.ca 1-888-414-1336 Table of Contents Page Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 1 Sommaire .............................................................................................................................. 2 Overview ............................................................................................................................... 4 Origin .............................................................................................................................. 4 Mountain Biking Disciplines ............................................................................................. 4 Types of Mountain Bicycles .............................................................................................. 7 Emerging Trends .............................................................................................................. 7 Associations .......................................................................................................................... 8 International ................................................................................................................... -

Gorsko Kolesarjenje, Razvijajoča Se Športno-Rekreativna Dejavnost

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA ŠPORT Športna vzgoja GORSKO KOLESARJENJE, RAZVIJAJOČA SE ŠPORTNO-REKREATIVNA DEJAVNOST DIPLOMSKO DELO MENTOR: doc. dr. Matej Majerič, prof. šp. vzg. Avtor dela RECENZENT LUKA POSAVEC prof. dr. Stojan Burnik, prof. šp. vzg. Ljubljana, 2014 ZAHVALA Zahvaljujem se mentorju doc. dr. Mateju Majeriču za strokovno pomoč pri izdelavi diplomskega dela. Zahvaljujem se tudi staršem in sestri, ki so mi ves čas študija stali ob strani in me spodbujali. Ključne besede: gorsko kolesarstvo, oprema, vožnja v naravnem okolju, zakonodaja, vplivi na okolje, konflikt, razvijanje turizma GORSKO KOLESARJENJE, RAZVIJAJOČA SE ŠPORTNO-REKREATIVNA DEJAVNOST Luka Posavec IZVLEČEK Gorsko kolesarstvo postaja v Sloveniji športno-rekreativna dejavnost, s katero se ukvarja vedno več ljudi. Pri tej dejavnosti so udeleženci v stiku z naravo, aktivnost vpliva na njihove motorične in funkcionalne sposobnosti in ima pozitiven vpliv tudi na telesno in duševno zdravje. Problem te športno-rekreativne dejavnosti nastane takoj, ko se gorski kolesar pojavi v naravnem okolju, saj ima po prepričanju mnogih gorsko kolesarjenje negativne vplive na okolje. V Sloveniji je od leta 1995 vožnja v naravnem okolju urejena z Uredbo o prepovedi vožnje z vozili v naravnem okolju, junija 2014 pa je Državni zbor RS soglasno sprejel novelo Zakona o ohranjanju narave. Namen zakona je, da se tudi v naravnem okolju vožnja omeji le na prometno infrastrukturo, vožnja izven cest pa v celoti prepove in ustrezno kaznuje, pri čemer je glavni cilj, da se preprečijo škodljive posledice vožnje z vozili na motorni pogon in lasten pogon na neutrjenih površinah. Poseben problem predstavljajo tudi nasprotja med kolesarji in drugimi uporabniki naravnega okolja. -

Senior Industrial Design Thesis Adam Carlson

Senior Industrial Design Thesis Adam Carlson Table of Contents About Me 2 | Adam Carlson | Senior Thesis Senior Thesis | Adam Carlson | 3 Mountain biking is an area of the bike industry that has grown immensely from the point of its birth some thirty years ago. Development of advanced suspen- Project sion systems allowed riders to take their bikes to the unknown territory of off oadr discovery. Today four different sports or subtitles exist under the mountain bike Aim title, they are: Downhill, Enduro/Techical, Singletrack, and Cross Country. Downhill being the most technical and demanding of a bikes suspension and Cross Country The vision of this project is to give being the easiest to ride and small amounts of suspension needed. Current mar- mountain bike users a new system ket strategies have developed multiple lines of bikes to satisfy different design and to improve comfort and usability of suspension characteristics of each category. The result is bikes that excel in their riding off road full suspension moun- designed category but lack characteristics to succeed in other categories. tain bikes. Ideally the final solution will allow new riders the ability to After working in the bike industry for an internship, one thing stood out. A gap, come into the market at a lower price point and be able to ride on tougher which could be filled with a new type of mountain bike concept. The gap provided more technical terrain without the that there was no one bike that could take advantage of all or many of the sports need of lots of prior experience. -

June 2003 Issue

VOLUME 11 NUMBER 4 FREE JUNE 2003 cyclincyclingg utahutah •Calendar of Events - p. 14 Over 200 Events to choose from! •Ogden’s’s WheelerWheeler CreekCreek TTrail - p. 3 •Results - p. 16 •Provo Bike Committee - p. 4 •Brian Head Epic Preview - p. 20 •The Joyride - p. 11 •SAFETEA - p. 7 •DMV Crit Series - p. 10 •Coach’s’s CornerCorner -- p.p. 99 •Cipo and the Giro - p. 2 •Bike Touring on the West Coast - p. 19 MOUNTAIN WEST CYCLING JOURNAL MOUNTAIN WEST CYCLING JOURNAL •Bike Club Guide - part IV - p. 6 2 cycling utah.com JUNE 2003 SPEAKING OF SPOKES busts of 1999. things finally came together for ever watched. The last kilome- I was excited when Cipo won him, and he tied and then broke ter of the finishing climb on the six stages of the Giro last year, Binda’s record, life was as it Monte Zoncolan seemed to take pulling within one stage win of should be, and for this fan it felt forever, even prompting Phil, CipoCipo andand thethe GiroGiro Alfredo Binda’s record 41 stage good. Then, even as I was hop- Paul and Bob to comment that wins in the Giro. I have been ing for more stage wins for this was the longest kilometer of waiting since then to see him tie Cipo, my heart was broken as he racing they could remember. By Dave Ward and then exceed Binda’s record. was taken down on a wet corner The pain on the faces of the Publisher Then, I was ecstatic when just as he was about to sprint to stage leaders Simoni, Stefano Mario won the World Road Race the finish line in San Dona. -

IPMBA News Vol. 12 No. 1 Winter 2003

Product Guide Winter 2003 ipmbaNewsletter of the International Police newsMountain Bike Association IPMBA: Promoting and Advocating Education and Organization for Public Safety Bicyclists. Vol. 12, No. 1 IPMBA’s First Product Guide GOING THE DISTANCE By Maureen Becker The thrill of the “chase.” Executive Director By Deputy Chief Rick Concepcion, PCI #606 elcome to the first IPMBA News of 2003! Not only is this Winthrop Harbor PD (IL) the first issue of the New Year, it is also IPMBA’s first Ed’s Note: The annual IPMBA public safety cyclist competition is official “product guide.” We started thinking about scheduled for Friday, May 23, 2003, in Charleston, West Virginia. This W article is sure to inspire you to join your fellow bike officers and medics putting together a product guide after several IPMBA members and share your skills and experiences. For more information about the suggested it during the 2001 membership survey. When Industry conference, including the competition, visit www.ipmba.org. Liaison Monte May of the KCMO Police Department mentioned it olice bike officers are some the most highly to the members of the Industry Relations Committee (IRC), they motivated and competitive police officers in the jumped all over it, and articles were soon pouring into the IPMBA P world. All of the Winthrop Harbor bike officers office. Seems like that group just loves to talk “tech.” must successfully complete the 32-hour IPMBA Police Because of that, this is not going to be your typical product guide, Cyclist Course before they are allowed to ride. And just comprised only of page after page of company listings. -

M a T Ja Ž O G Ris 2014 M a G Is T Rs K a N a L O G a Univerza Na Primorskem Fakulteta Za Management Matjaž Ogris Koper, 2014

UNIVERZA NA PRIMORSKEM 2014 2014 FAKULTETA ZA MANAGEMENT MAGISTRSKA NALOGA MATJAŽ OGRIS MAGISTRSKA NALOGA NALOGA MAGISTRSKA MATJAŽ OGRIS MATJAŽ KOPER, 2014 UNIVERZA NA PRIMORSKEM FAKULTETA ZA MANAGEMENT Magistrska naloga PRAVNI VIDIKI IN MOŽ NOSTI ZA RAZVOJ GORSKEGA KOLESARSTVA NA KOROŠKEM Matjaž Ogris Koper, 2014 Mentorica: doc. dr. Da nila Djokić Somentor: red. prof. dr. Stojan Burnik POVZETEK Magistrska naloga raziskuje pravnosistemske možnosti in vidike za umestitev gorskega kolesarstva v naravno okolje na Koroškem. Primerjava z avstrijsko zvezno deželo Koroško in Tirolsko ter nemško zvezno deželo Bavarsko pokaže, da pravne podlage vožnje v naravnem okolju Republike Slovenije ovirajo razvoj gorskega kolesarstva. V nekaterih primerjalnih deželah Avstrije in Nemčije je to ustrezno urejeno s primerno zakonodajo in vzpodbudami na zvezni ravni. Empirični del naloge predstavlja kvantitativna raziskava o pojavnosti konfliktov med gorskimi kolesarji in planinci/pohodniki pri rabi planinskih poti na Koroškem. Rezultati anketnega vprašalnika kažejo, da konflikti niso vzrok nepopolnega razvoja gorskega kolesarst va, saj se ti v povprečju pojavljajo v manj kot petih odstotkih vseh medsebojnih srečanj. Ugotovljena je tudi pomembna razlika o zaznavanju gorskega kolesarstva v naravnem okolju med planinci/pohodniki in gorskimi kolesarji. Naloga pomembno prispeva k reše vanju urejanja vožnje z gorskimi kolesi v naravnem okolju. Ključne besede : gorsko kolesarstvo, zakonodaja, konflikt, razvoj, Koroška. SUMMARY In the master's thesis, legal possibilities and prospects of placing mountain biking in the natural environment of Carinthia are explored. Comparison with the Austrian federal states of Carinthia and Tyrol and the German free state of Bavaria reveals that the growth of mountain biking is hindered by the legal basis for driving on the natural environment of the Republic of Slovenia. -

'Any Colour You Want 7I As Long As It's Black!"

''Any colour you want 7i as long as it's black!" When Henry Fo rd said of his Model T automobile that it came in any colour as long as it was black, he was restricting choice. Bell helmets do the opposi te. \Y/e recognise that all cyclists are different. What the racer want in a helmet is not the same as a tourer. A triathlete has different needs to a recreational rider and o on. You can have any helmet you want as long as its a Bell. \X 'e inl'ented the hard she ll bic\'cle helmet \Yal' back in 1r5 and since then ,l'e hal'e been the undisputed leader in helmet technology. Contin uouslv tri,·ing to not only make helmets more protective but lighter, cooler and more comfonahl e as ~·e ll. \\ 'e are also a,l'are of the dil'erse needs of cycl ists. That's why our range no~· offers JO models in a wide range of sizes and colours. ,\lost imponanrly th e\' all conform to the exacting safety C • standard. ,·ou ~mild expect from the ~·orld '. most respected helmet manufacturer. Inspect the fu ll range of Be ll cyc ling helmets today at rnur nearest specia li st biC\·cle retailer. You're different; that's why you choose Bell. Regular columns 16 CALENDAR 16 CLASSIFIEDS 12 PRO DEALERS 5 WARREN SALOMON 39 PHIL SONERYILLE Contents 36 WERNER'S WINNING t WORLD AWHEEL Mountain bike feature WAYS Freewheeling interviews Freewheeling is published seven times a year in the It CHANP NANES 1117 months of January, March, May, July, September, October the MTB champ an d November. -

Trek Aluminum Frame Crack

Trek aluminum frame crack click here to download It's frame material is platinum aluminum alloy. Eventually, you'll develop a crack somewhere, it'll propagate, and the frame is toast. The "platinum aluminum alloy" sounds a lot like a Trek, in which case "platinum" is just. Picked up a trek this past weekend. new tires& tubes, He explained that these old aluminum frame bikes were simply pressed. He told me that the best I could do was to get a Trek 5 series frame for 20% off I' d bet that Trek will honor the warranty if the cracks were not caused by a the bonded in aluminum bb shell disassociated itself from the frame. Basically Trek will not honour there "lifetime" frame warranty on the basis that I Hi I'm currently going through a process of a cracked frame with de Rosa Unfortunately the is Aluminium though so that's not possible - but. There's nothing special about building a bicycle frame which is merely light. The ratio of stiffness to weight of aluminum exceeds that of all other materials which . to the applied force, and shuts down the test when a substantial crack develops. Cannondale, Principia and Trek withstood the test without failure, and the. Advice on cracked Aluminum frame repair - posted in Tech Q&A: Is it worth it or possible to fix a crack on my aluminum frame? The crack is. I have a Trek that I have been using for my outdoor rides this winter. My concern is that I have been told that aluminum frames loose strength at I have inspected the frame and see no signs of cracking but I don't. -

16 CYCLIST.CO.UK £5.99 Autumn 2019

#02 9 78178116 CYCLIST.CO.UK067208 £5.99 Autumn 2019 CONTENTS Issue #02/ Autumn 2019 94 Shadow Of The Stelvio Cyclist Off-Road heads to one of the most famous climbs known to two wheels – and takes a detour onto the stunning tracks you don’t normally get to see CYCLIST.CO.UK 9 CONTENTS Gear 15 Ten pages of all the kit you’ll need to get the most out of riding off-road, from Shimano, Easton, Pirelli, DT Swiss and a host of others 112 Battle On 70 Dirty Kanza The Beach Rides 35 This issue our thirst for adventure takes us to the volcanoes of Iceland, the shadow of the Stelvio in Italy and the depths of rural Sussex – plus the UK’s Battle On The Beach and Dirty Kanza in the US 84 A Trip Back In Time 94 Italy 36 Iceland 54 Sussex On test 125 Cyclist Off-Road puts three of the latest gravel machines from Cannondale, Santa Cruz and Open through their paces Knowledge 145 Want to be a better rider? We’ve got all the insider tips on how to descend faster, fit tubeless tyres, pick the right kit, pack for a multiday adventure and lots more 10 CYCLIST Ed’s Letter Switchboard: +44 (0)20 3890 3890 Advertising: +44 (0)20 3890 3801 Subscriptions: 0330 333 9492 Emails: [email protected] Cyclist, Dennis Publishing, 31-32 Alfred Place, London WC1E 7DP Web: cyclist.co.uk Email: [email protected] Facebook: facebook.com/cyclistmag Instagram: cyclist_mag Twitter: twitter.com/cyclist EDITORIAL Editor Pete Muir Deputy Editor Stu Bowers Art Director Rob Milton Production Editor Martin James Features Editor James Spender Commissioning Editor Peter Stuart Staff Writer Sam Challis Website Editor Jack Elton-Walters Web Writer Joseph Robinson App production/subbing Michael Donlevy Cover image Mike Massaro ADVERTISING Advertising Manager Adrian Hogan Account Manager Alex Law Senior Sales Executive Ben Lorton Agency Account Manager Rebecca New he six months since we launched Cyclist Off-Road have been some of the most PUBLISHING, MARKETING AND SUBS enlightening of my 30-plus years spent riding. -

Wikipress 8: Fahrräder

WikiPress Fahrräder Für viele Menschen ist das Fahrrad ein Alltagsgegenstand, den sie wie Fahrräder selbstverständlich benutzen. Spätestens jedoch, wenn irgendetwas nicht funktioniert, macht man sich Gedanken über die Funktionsweise der Technik, Typen, Praxis Teile. Dieses Buch ist keine Reparaturanleitung, sondern erklärt die vielfäl- tigen Fahrradtypen sowie den Aufbau von Schaltungen, Bremsen und Be- Aus der freien Enzyklopädie Wikipedia leuchtungen mit ihren Vor- und Nachteilen. Auf das wichtigste Zubehör zusammengestellt von – von der Packtasche bis zur Luftpumpe – wird ebenso eingegangen wie auf Fahrradwerkzeug und die passende Bekleidung. Doch nicht nur die Ralf Roletschek Fahrradtechnik wird dem Leser leicht verständlich näher gebracht, er fin- det in diesem Buch auch Tipps zu Radtouren quer durch ganz Deutsch- land. Ralf Roletschek wurde am 5. 2. 1963 in Eberswalde (Kreis Barnim im Bundesland Brandenburg) geboren, ist in der Stadt aufgewachsen und hat die 10-klassige allgemeine polytechnische Oberschule der DDR besucht. Er hat den Beruf des »Facharbeiters für Holzbearbeitung« mit Abitur er- lernt. Diese Berufsform war in der ehemaligen DDR eine verbreitete Be- rufsausbildung, bei der neben der praktischen Arbeit das Abitur erworben wurde. Im Jahr 1990 hat er das Bauingenieurstudium als Tiefbauinge- nieur beendet. In den Folgejahren war er als Bauingenieur und Dozent (Erwachsenenqualifizierung CAD, Erstausbildung Informatikkaufleute, Umschulung Fahrradmonteure) in Spanien und Deutschland tätig und ist derzeit Gastdozent der Fachhochschule Eberswalde. Ralf Roletschek hat als Amateurfotograf seit 1979 erfolgreich an Ausstellungen in vielen Ländern teilgenommen und arbeitet gelegentlich als Pressefotograf für regionale Redaktionen. Er fährt gern mit seinem Reiserad durch das Bio- sphärenreservat Schorfheide-Chorin, fotografiert dabei und schreibt bar- WikiPress 8 rierefreie Homepages. -

Download the 2019 Industry Directory

2019 INDUSTRY DIRECTORY A SUPPLEMENT TO IN COLLABORATION WITH Journalism for the trade Bicycle Retailer & Industry News connects dealers and industry executives throughout North America, Europe and Asia. Whether through our highly tra cked website, email blasts or print, we reach the global bicycle market year-round. Our readers have come to expect a keen focus on analysis, trends, data and the day-to-day reporting of major events a ecting the industry. SALES Sales - U.S. Midwest Sales - Europe Kingwill Company Uwe Weissfl og Respected • Frequent Barry and Jim Kingwill Cell: +49 (0) 170-316-4035 Tel: (847) 537-9196 Tel: +49 (0) 711-35164091 Fax: (847) 537-6519 uweissfl [email protected] Infl uential • Trustworthy [email protected] [email protected] Sales - Italy, Switzerland Ediconsult Internazionale Subscribe to our email newsletters: Sales - U.S. East Tel: +39 10 583 684 www.bicycleretailer.com/newsletter Karl Wiedemann Fax: +39 10 566 578 Tel: (203) 906-5806 [email protected] Get our print or digital edition: Fax: (802) 332-3532 www.bicycleretailer.com/subscribe [email protected] Sales - Taiwan Wheel Giant Inc. Follow us on social media: Sales - U.S. West Tel: +886-4-7360794 & 5 Ellen Butler Fax: +886-4-7357860 facebook.com/bicycleretailer twitter.com/bicycleretailer Tel: (720) 288-0160 Fax 2: +886-4-7360789 [email protected] [email protected] youtube.com/bicycleretailer instagram.com/bicycleretailer Digital Advertising Statistics for BicycleRetailer.com pageviewsmonth 1004 x 90 uniquevisitsmonth pagespersession minutespersession 300x250 Fanatics usersvisitthesite anaverageofxmonth Background Background mobiledesktop takeover takeover socialsharesmonth 300x600 Visitor Demographics 428x107 Male Female 25-55 example ad sizes $100k+ College or graduate school Weekly Newsletters Currently, the editorial staff produces two newsletters each week—a Based in the U.S.