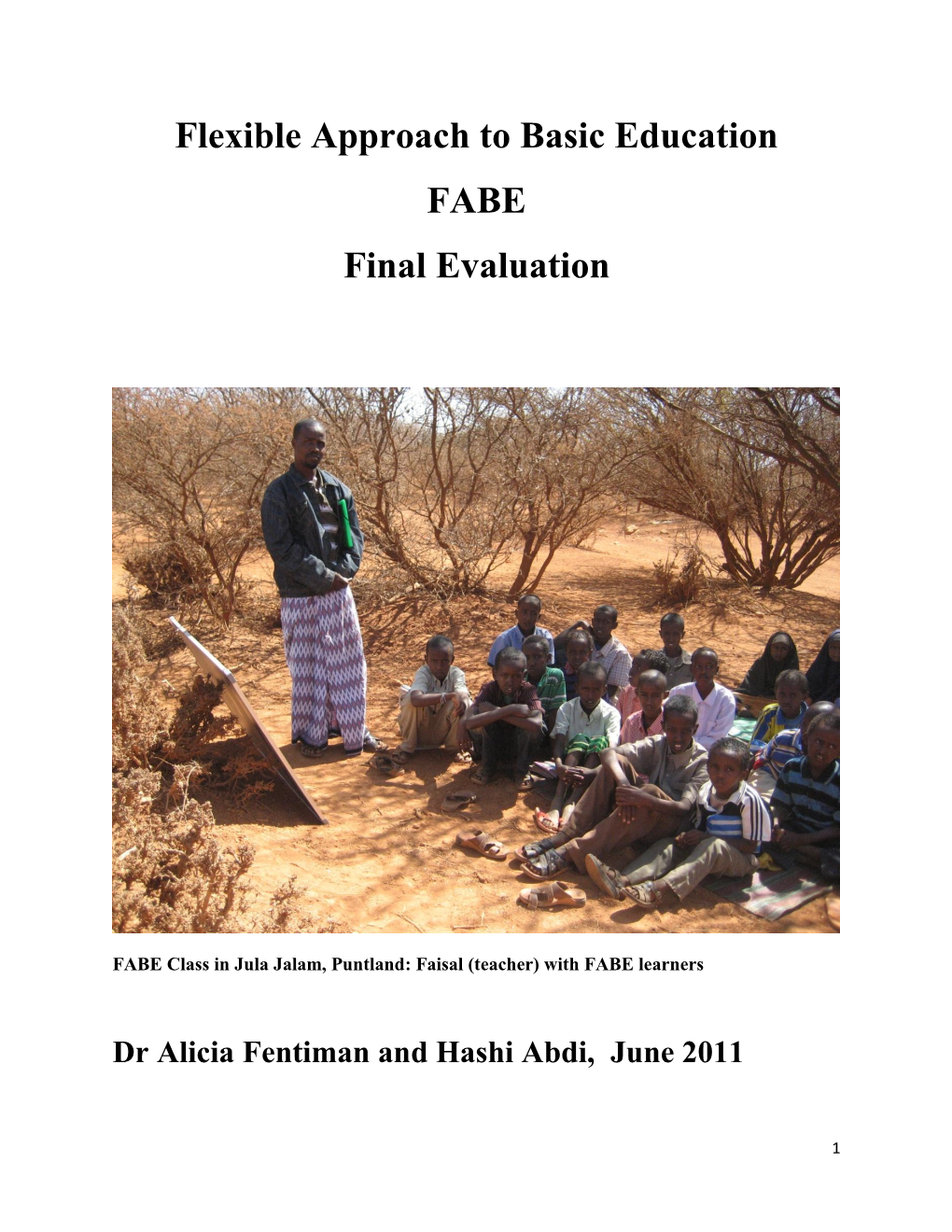

Flexible Approach to Basic Education FABE: Final Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Security Council Distr.: General 18 February 2005

United Nations S/2005/89 Security Council Distr.: General 18 February 2005 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Somalia I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to the statement of the President of the Security Council of 31 October 2001 (S/PRST/2001/30), in which the Council requested me to submit reports on a quarterly basis on the situation in Somalia. The report focuses on developments regarding the national reconciliation process in Somalia since my previous report, of 8 October 2004 (S/2004/804). It also provides an update on the security situation as well as the humanitarian and development activities of United Nations programmes and agencies in Somalia. II. The formation of the Transitional Federal Government 2. The Somali National Reconciliation Conference concluded on 14 October 2004 with the swearing-in of Colonel Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed as the President of Somalia. He was elected by the members of the Transitional Federal Parliament of Somalia on 10 October 2004 after three rounds of voting. In the final round, Colonel Yusuf obtained 189 votes while the runner-up candidate, Abdullahi Ahmed Addow, obtained 79 votes. Mr. Addow accepted the outcome and pledged to cooperate with the President. Prior to the vote, all 26 presidential candidates signed a declaration to support the elected President and to demobilize their militias. 3. On 3 November, President Yusuf appointed Ali Mohammed Gedi, a veterinarian and member of the Hawiye clan, predominant in Mogadishu, as Prime Minister of the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia. 4. During the first week of December, Prime Minister Gedi announced the appointment of some 73 Ministers, Ministers of State and Assistant Ministers. -

1 MINISTRY of EDUCATION & SCIENCE REPUBLIC of SOMALILAND Fifth Draft GLOBAL PARTNERSHIP for EDUCATION PROGRAM 2018-2021 Nove

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION & SCIENCE REPUBLIC OF SOMALILAND Fifth Draft GLOBAL PARTNERSHIP FOR EDUCATION PROGRAM 2018-2021 November, 2017 1 ACRONYMS AAGR Annual Average Growth Rate ABE Alternative Basic Education ADRA Adventist Development and Relief Agency AET Africa Education Trust CA Coordinating Agency CEC Community Education Committee CRM Complaint Response Mechanism DEO District Education Officer DFID Department For International Development (UK) ECE Early Childhood Education EDT Education Development Trust EFPT EMIS Focal Point Teacher ERGA Early Grade Reading Assessment EiE Education in Emergencies EMIS Education Management Information System ESA Education Sector Analysis ESPIG Education Sector Plan Implementation Grant ESSP Education Sector Strategic Plan ESC Education Sector Committee EU European Union GA Grant Agent GDP Gross Domestic Product GER Gross Enrolment Rate GFS Girl Friendly Space GPE Global Partnership for Education GPI Gender Parity Index IDP Internally Displaced People INGO International Non-Governmental Organization IPTT Indicator Performance Tracking Table IQS Integrated Quranic Schools JRES Joint Education Sector Review KRT Key Resource Teacher MEAL Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning MLA Measuring Learning Achievement MOES Ministry of Education & Science MOERA Ministry of Endowment and Religious Affairs MOH Ministry of Health MoU Memorandum of Understanding M&E Monitoring and Evaluation NDP National Development Plan NFE None Formal Education NGO Non-Governmental Organization NRC Norwegian Refugee -

Final Report of the Somali Interactive Radio Instruction Program

final rePort of the Somali interactive radio instruction Program Place pull quote here damwf lkars hifas lacsdef acs dfleas dfl sayd f askdef pasdfy hifas lacsdef acs dfleas dfl sayd f askdef pasdfy Final RePoRt of the Somali interactive radio inStruction Program i Contents Chapter 1. executive summary ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2. introduction .......................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 3.achievements of the somali interactive Radio instruction Program ..........................8 3.1 Tangible results: siRiP helped somali children learn more. .....................................8 3.1.1 enrollment numbers .............................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2 learning gains: 2007 student assessment ........................................................................ 9 3.1.3 learning gains: 2010-2011 student assessment................................................................10 3.2 Expanding opportunity: siRiP provided access to learning and educational resources where there were none. .............................................. 12 3.2.1 enrollment of out-of-school, idP, and marginalized learners ...................................... 13 3.2.2 enrollment in SiriP-supported Quranic schools ............................................................ 13 3.2.3 addressing gender equity ................................................................................................. -

Post-Conflict Education Development in Somaliland

Post-Conflict Education Development in Somaliland Post-Conflict Education Development in Somaliland Samuel Ayele Bekalo, Michael Brophy and Geoff Welford Abstract In the light of fresh international initiatives to achieve Universal Basic Education (UBE) and gender equality in education by 2015, this paper examines factors affecting its realisation in the context of Somaliland. In a country where over 80% of school age children are receiving little meaningful education, the paper reflects on more flexible education approaches to provide sustainable education for children and disadvantaged adults. The paper draws on fieldwork data from a DfID funded study [1] and the authors' own experiences. The discussion highlights the peculiar circumstances of Somaliland. It charts the provision of Education in the then Somalia from the colonial era through post-independence times to the civil conflict which led to the destruction of education in the country. It goes on to look at the progress being made at the present time following “stop-gap” measures for emergency education towards revitalising enhanced education. It completes the picture by describing challenges to the achievement of the UBE target. The authors review aspects of alternative and flexible educational approaches and urge the integration of these non-formal systems with the formal, governmentally controlled school systems being restored in Somaliland. They do so while sounding a note of caution that for all the energy and enthusiasm associated with these approaches, they have yet to be evaluated for their effectiveness in providing quality basic education. This paper looks at education in Somaliland. It presents a brief summary of the development of education from colonial times, through the recent civil conflict into the present time. -

REPUBLIC of SOMALILAND MINISTRY of EDUCATION and HIGHER STUDIES Education Sector Strategic Plan (ESSP 2017-2021) October 2017

REPUBLIC OF SOMALILAND MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND HIGHER STUDIES Education Sector Strategic Plan (ESSP 2017-2021) October 2017 Supported by: i Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................. vi List of Tables ............................................................................................................... vii Foreword ..................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... x List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................... xii Executive Summary ................................................................................................... xvi 1. Context of the Education Sector Strategy Development ........................................ 1 1.1 Purpose of the Somaliland Education Strategic Plan 2017-21 ................................ 1 1.2 Methodology of the ESSP ...................................................................................... 1 1.2.1 Methodology .................................................................................................. 2 1.2.2. Education Sector Analysis ............................................................................ 2 1.2.3 ESSP Development Process ........................................................................ -

2010 Somaliland Child Rights Situation Analysis

Ministry of Justice Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs 2010 Somaliland Child Rights Situation Analysis 2010 Somaliland Child Rights Situation Analysis The partners in this study, who also financially and technically contributed to the study that was coordinated by Save the Children are: Save the Children, UNICEF, CESVI, SOS Children´s Villages, and ADRA. Disclaimer: This report was commissioned by Save the Children and produced by an independent consultant. The opinions expressed in the report do not necessarily reflect the official position and views of any of the agencies who contributed to the study. Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 9 1. CRSA Methodology ............................................................................................................... 11 2. Context .................................................................................................................................. 16 2.1 Children’s Rights: A Reminder ..................................................................................................................... 16 2.2 Somaliland ~ The Environment for Children and their Rights .............................................................. 18 2.3 Who is a Child ................................................................................................................................................ -

The Gaboye of Somaliland: Legacies of Marginality, Trajectories of Emancipation

University of Milan-Bicocca “Riccardo Massa” Department of Human Sciences for Education Doctoral Programme in Cultural and Social Anthropology Cycle XXIX THE GABOYE OF SOMALILAND: LEGACIES OF MARGINALITY, TRAJECTORIES OF EMANCIPATION Elia Vitturini Registration number 734232 Tutor: Prof. Alice Bellagamba Coordinator: Prof. Ugo E.M. Fabietti ACADEMIC YEAR 2017 A Mascia e Olga. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 3 PART I 18 WHO ARE THE GABOYE? STUDYING WRITTEN SOURCES AND THE SEARCH FOR CONCEPTUAL TOOLS 18 CHAPTER 1 18 DOCUMENTING THE SUBORDINATION OF THE GABOYE 18 1.1 WRITTEN SOURCES ON THE SUBORDINATION OF THE GABOYE 18 1.2 THE REVIEW OF THE WRITTEN SOURCES OF COLONIAL TIMES 20 1.3 THE DEBATE ABOUT ORIGINS 35 1.4 DOCUMENTING THE SUBORDINATED GROUPS’ SOCIAL POSITION BETWEEN PAST AND PRESENT 41 CHAPTER 2 64 THE ACADEMIC DEBATE AROUND ‘CASTES’ IN AFRICA 64 2.1 THE PEREGRINATIONS OF THE CONCEPT OF ‘CASTE’ ACROSS TIME AND SPACE 64 2.2 PAST AND FUTURE TRAJECTORIES OF THE CONCEPT OF ‘CASTE’ WITHIN AFRICAN STUDIES 68 2.3 RENEWING COMPARATIVE DIALOGUE 73 PART II 78 THE ROUTE OF EMANCIPATION IN THE TOWN OF HARGEYSA 78 EMANCIPATION IN THE SOMALI TERRITORIES 78 CHAPTER 3 82 THE TOWN OF HARGEYSA: THE SETTING OF THE GABOYE’S EMANCIPATION 82 3.1 BRITISH WRITTEN SOURCES: 1880s-1940 82 3.2 HARGEYSA AS THE NEW CAPITAL OF THE PROTECTORATE: 1941-1960 95 3.3 URBANISATION AND SOCIAL CHANGE 119 CHAPTER 4 121 THE GABOYE’S ORAL HISTORY 121 4.1 REPRESENTING THE PAST 121 4.2 ORAL HISTORY ABOUT THE ORIGINS OF HARGEYSA 123 4.3 ORAL HISTORY AND HARGEYSA’S FIRST WAVE OF EXPANSION 128 4.4. -

Fulltextthesis.Pdf

An Analytical Understanding of How External Sources Inform and Impact Upon Somaliland’s National Education and Teacher Education Policy Making Processes A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Hassan Suleiman Ahmed School of Sport and Education Brunel University August 2009 1 Abstract This thesis investigates how external sources inform and impact Somaliland‟s national teacher education policy making processes. In this research, external factor is mainly constituted by INGOs that are helping Somaliland‟s education and teacher education re- construction which are considered to be part of wider global-national interactions. The conceptual frameworks of policy making processes, policy transfer, lesson drawing and policy learning are used to develop the theoretical perspectives that inform the research question. Constructivist‟s qualitative research approach which utilises critical discourse analysis as the principle methodology has been used to gain an understanding of the discursive construction of meaning about Somaliland‟s education reforms and analyse the discourses of teacher education and teacher professionalism that are evident in three contemporary education reform policy documents and interview data. This thesis considered policy making processes as a contested, dynamic and multidimensional phenomena and has acknowledged the centrality of power and resources in policy making processes. The analysis of the research data constructed Somaliland‟s education reforms as a discourse of human capital. This had implications for the strategies for managing change, quality and improvement perception, and reconceptualisations of teacher education and teacher professionalism. The thesis concludes with concerns about the contextual visibility to implement the new discourses of education and teacher education and calls for increased policy learning, capacity building, resource increase and modernisation of institutions as well as change of the culture of work. -

Thesisxxsaxlinusson.Pdf (1.228Mb)

Students´ and guardians´ views and experiences with the Alternative Basic Education (ABE) program in the Amhara National Regional State of Ethiopia Åsa Elisabeth Linusson Master of Philosophy Comparative and International Education Institute for Educational Research UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Fall 2009 Abstract The objective of this study was to investigate how participants and guardians of participants perceive the quality and relevance of the Alternative Basic Education (ABE) program in the Amhara National Region of Ethiopia. The ABE program is a condensed version of the first cycle of Formal primary school (grades 1-4) and is a variation of Non-formal education (NFE) with features similar to the `community school´ approach to education. The interest in the program and the research focus arose from the fact that the Ethiopian educational authorities, like governments in several other developing countries have embraced this type of educational programs, apparently in an attempt to achieve Education For All. In 2005/06 the Gross Enrolment Ratio in ABE was at least 5, 5 % in Ethiopia and a steadily increasing share of the school age population is enrolled in the program. Findings on previous research on this type of NFE initiatives indicate that on one hand this type of approaches to education may be more relevant and accessible to the learners and the communities, including that it may enhance the participation of girls and marginalized populations. It may also be less costly to both the implementers and the communities than Formal education. On the other hand there were concerns expressed in the reviewed literature over that NFE in reality may be, or be perceived as being, of second rate to Formal education, and thus neither be more relevant to the communities nor enhance the demand and participation in education. -

Somalia/Somaliland Background Paper

January 2021 Transforming Education for Sustainable Futures: Somalia/Somaliland Background Paper Somalia/Somaliland Background Paper Acronyms Contents ABE Alternative Basic Education Introduction....................................................................................................................... 3 Sustainable Development ......................................................................................... 3 ECE Early Childhood Education Education for (Un)Sustainable Development ................................................ 5 EIE Education in Emergencies TVET Case Study ........................................................................................................ 7 SDG 4 – Quality Education ....................................................................................... 8 ESD Education for Sustainable Development Education and SDG 8 - Decent Work and Economic Growth ........... 13 ESSP Education Sector Strategic Plan Education and SDG 11 - Sustainable Cities and Communities ......... 14 Education and SDG 13 - Climate Action ........................................................ 14 FGS Federal Government of Somalia Conclusion: Transforming Education to support Sustainable GDP Gross Domestic Product Development .................................................................................................................. 16 References ........................................................................................................................ 17 GER Gross Enrolment Rate GPI Gender -

Republic of Somaliland Education Statistics

Republic of Somaliland Education Statistics Yearbook 2013/2014 Ministry of Education and Higher Education Department of Planning and Policy Data and Statistics (EMIS) unit March 2015 Hargeisa, Republic of Somaliland Website: www.moehe.com Department of Planning and Policy Data and Statistics Unit (Education Management Information System) Hargeisa, Somaliland Tel: +252 63-4417068 Website: www.moehe.com Email: [email protected] © Ministry of Education and Higher Education This publication may be used in part or as a whole, provided that the EMIS is acknowledged as the source of the information. Whilst the EMIS does all it can to accurately consolidate and integrate Somaliland education information, it cannot be held liable for incorrect data and for errors in conclusions, opinions and interpretations emanating from the information. Furthermore, the EMIS cannot be held misinterpretation of the statistical content of the publication. This publication has been produced with financial support from the government of the Netherlands through the Peace Building, Education and Advocacy (PBEA) programme and technical assistance from UNICEF. A complete set of the yearbook will be available at the following addresses: • EMIS Unit, MOEHE, Hargeisa, Somaliland • MOEHE’s website: www.moehe.com For more inquiries or requests, please use the following contact information: Mohamed Ibrahim, Director General, MOEHE Somaliland, [email protected] Ahmed Qulle, Director of planning and policy, MOEHE Somaliland, [email protected] Ubah Duale, EMIS Focal Person, -

Somaliland Academic Staff: Identity, Functions, and Institutional Development

Somaliland Academic Staff: Identity, functions, and institutional development Thomas J. Jones I. Introduction The functions of higher education systems in Sub-Saharan African societies have been criticized for their colonial establishment, chronic lack of support due to structural adjustment era policies, low stand- ing in international ranking competitions, and privatization (Cloete, Maassen, & Bailey, 2015). This criticism has come during a time of rapid system expansion globally as well as regionally (Areaya, 2010). Though higher education policy sharing and international pressure to compete in regional or global rankings pushes African universities toward functions that are similar to Northern institutions, most are not able to come close to matching resources, organizational culture or structure, or staffing needs that results in similar academic identity, functionality, or institutions. This paper draws on the survey and interview responses of academ- ics in Somaliland to shed light on the underlying function of higher education in the region and to compare this with cross-national stud- ies from the higher education literature focused on research-based, ‘world class’ institutions. The pressure on academic work due to sys- tem expansion, diversification, and institutional development globally has meant that the traditional roles, training, and characteristics of academic faculty are in a state of flux (Altbach, Reisberg, Yudkevish, Androushchak, & Pacheco, 2012; Gappa, Austin, & Trice, 2006). For Somaliland, answering the question of faculty roles in new institu- 12 Thomas J. Jones tional development as well as showing the policy change needed in lieu of changing functions comes at a critical time. II. The Somaliland Context For over twenty years, Somaliland has acted as an independent state from Somalia.