Grant County Pud Under the Clean Water Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary Report Appraisal Assessment of the Black Rock Alternative

Summary Report Appraisal Assessment of the Black Rock Alternative A component of Yakima River Basin Water Storage Feasibility Study, Washington Technical Series No. TS-YSS-7 Black Rock Valley U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Pacific Northwest Region December 2004 The mission of the U.S. Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Yakima River Basin Water Storage Feasibility Study, Washington Summary Report Appraisal Assessment of the Black Rock Alternative Technical Series No. TS-YSS-7 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Pacific Northwest Region FRONTISPIECES Cashmere h Bend Main Map Legend REGIONAL REFERENCE Major Dams / Diversion Dams Major Roads e Ditch, Canal, etc. in Streams Wenatchee Water Bodies Pipel City Boundaries -K WASHINGTON s Dam Yakima River Basin Boundary K u e Coeur d'Alene e tial K c h [_ Yakama Nation Boundary e [_ l u ten [_ s o Seattle L P Odessa Yakima Project Divisions a Keechel Spokane k m e ! ! K ! ! a Ephrata Government Reservation ! ! c Da h YAKIMA e s s RIVER L C County Boundaries a l k chesse e BASIN E l u Ka m Chelan County [_ L a k Lake e Yakima Easton Grant County Cle Elum Dam Kittitas County Douglas County Quincy Roslyn -

Priest Rapids Hydroelectric Project—FERC Project No

FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT AMENDING LICENSE TO MODIFY RIGHT EMBANKMENT OF THE PRIEST RAPIDS DAM Priest Rapids Hydroelectric Project—FERC Project No. 2114-303 Washington Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Office of Energy Projects Division of Hydropower Administration and Compliance 888 First Street, NE Washington, DC 20426 January 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................. 4 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 6 1.1 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................... 6 1.2 AMENDMENT REQUEST AND NEED FOR ACTION .......................................... 7 A. Amendment Request .................................................................................................. 7 B. Need for Action .......................................................................................................... 8 1.3 PRE-FILING CONSULTATION AND PUBLIC NOTICE ....................................... 8 1.4. STATUTORY AND REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS...................................... 10 1.4.1 Section 18 Fishway Prescription ...................................................................... 10 1.4.2 Endangered Species Act ................................................................................... 10 1.4.3 Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act .................... 11 1.4.4 National Historic -

Dams and Hydroelectricity in the Columbia

COLUMBIA RIVER BASIN: DAMS AND HYDROELECTRICITY The power of falling water can be converted to hydroelectricity A Powerful River Major mountain ranges and large volumes of river flows into the Pacific—make the Columbia precipitation are the foundation for the Columbia one of the most powerful rivers in North America. River Basin. The large volumes of annual runoff, The entire Columbia River on both sides of combined with changes in elevation—from the the border is one of the most hydroelectrically river’s headwaters at Canal Flats in BC’s Rocky developed river systems in the world, with more Mountain Trench, to Astoria, Oregon, where the than 470 dams on the main stem and tributaries. Two Countries: One River Changing Water Levels Most dams on the Columbia River system were built between Deciding how to release and store water in the Canadian the 1940s and 1980s. They are part of a coordinated water Columbia River system is a complex process. Decision-makers management system guided by the 1964 Columbia River Treaty must balance obligations under the CRT (flood control and (CRT) between Canada and the United States. The CRT: power generation) with regional and provincial concerns such as ecosystems, recreation and cultural values. 1. coordinates flood control 2. optimizes hydroelectricity generation on both sides of the STORING AND RELEASING WATER border. The ability to store water in reservoirs behind dams means water can be released when it’s needed for fisheries, flood control, hydroelectricity, irrigation, recreation and transportation. Managing the River Releasing water to meet these needs influences water levels throughout the year and explains why water levels The Columbia River system includes creeks, glaciers, lakes, change frequently. -

Results of a PIT Tag Study at Priest Rapids Dam to Assess the Impact of the Whooshh Fish Transport System on Upstream Migrating Sockeye Salmon

Results of a PIT tag study at Priest Rapids Dam to assess the impact of the Whooshh Fish Transport System on upstream migrating Sockeye Salmon Conducted for Whooshh Innovations, LLC Jeffrey K. Fryer Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission 700 NE Multnomah Street, Suite 1200 Portland, OR 97232 January 15, 2017 Abstract Between June 29 and July 22, 2016, 897 Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) were PIT tagged at the Priest Rapids Dam Off Ladder Adult Fish Trap and released as part of a study to assess the impact of the Whooshh Fish Transport System (WFTS) on migrating salmon. During the first three weeks of the study, alternate groups of five Sockeye Salmon were sent via the WFTS or hand carried to the recovery area. Study fish were tracked upstream by PIT tag detections downloaded from www.ptagis.org. On July 22, WFTS tagged Sockeye Salmon were transported directly over the dam as opposed to going into the recovery area and continuing up the ladder, thereby missing detection at the top of Priest Rapids Dam. Wenatchee stock Sockeye Salmon were subsequently detected at Priest Rapids, Rock Island and Tumwater dams, while Okanogan stock Sockeye Salmon were subsequently detected at Priest Rapids, Rock Island, Rocky Reach, Wells, and Zosel dams. This study found no difference in survival between the WFTS and non-WFTS groups to either Wells or Tumwater dams combined over the entire study, however there were significant differences between the WFTS and non-WFTS groups in the distribution of Sockeye detected at individual dams that were likely attributable to differences in stock composition. -

Vantage Crossing

Vantage Crossing Crossing the Columbia River on I‐90 at Vantage is dramatic, even if routine. From either direction the highway drops over 1000 feet from the relatively lofty Columbia Plateau and crosses a 2500‐foot‐long bridge over Wanapum Dam Reservoir. You may be surprised to learn that in 1914 only two cars at a time could cross at one time on a rickety car ferry. Quick Timeline Before the Settlement Era ‐ The region along the Columbia River from the Beverly Gap (10 miles south of Vantage) to the Snake River was inhabited by the Wanapum tribe of Native Americans in prehistoric times and into the early exploration and settlement era. 1805 ‐ Lewis and Clark spend two days with the Wanapum people near the confluence of the Snake and Columbia Rivers. 1910 ‐ First Vantage townsite platted by Willard Van Slyke who divided it into 120 lots with a 20‐acre easement down the middle. 1914 ‐ Van Slyke establishes a two‐car ferry across the Columbia from the Vantage townsite. The Sunset Highway at this time connected Vantage and Ellensburg via the old Vantage Highway, north of I‐90. 1927 – Washington State Highway Department. (WSDOT) opens a 1,640‐foot, two‐lane cantilever bridge, replacing the car ferry. 1962 ‐ A steel tied‐arch bridge opens at Vantage as part of Interstate 90 traffic construction, above the expected level of water behind the soon to be finished Wanapum Dam. 1964 ‐ Wanapum Dam begins operations 1968 – I‐90 down and through Ryegrass Coulee is completed and traffic no longer goes through Vantage. -

Summary of the 2003 Mid-Columbia PUD Bull Trout Study Results Through 27 August 2003

Summary of the 2003 Mid-Columbia PUD Bull Trout Study Results through 27 August 2003 Detection Summary: • This summary includes fixed-site telemetry data through 27 August 2003 at Rock Island, Rocky Reach, and Wells dams; as well as the fixed-telemetry sites on the Wenatchee, Entiat, Methow, and Okanogan rivers. It also includes aerial survey data through 12 August 2003 and boat survey data through 22 July 2003. To date, three boat and three aerial surveys have been conducted during the 2003-2004 study period. Table 1 summarizes the last known location of all radio-tagged bull trout as identified by release location. • Monitoring of radio-tagged bull trout at the fixed-site telemetry systems at Priest Rapids and Wanapum dams concluded on 16 June 2003. Monitoring at those locations was conducted during Grant PUD’s radio-telemetry evaluation of smolt passage during the spring migration and concluded at the completion of that study. To determine if radio-tagged bull trout migrate downstream into the Grant PUD project area, we will rely on detections of tagged fish within the tailrace of Rock Island Dam. • For the 2003-2004 study period, no new bull trout were captured and tagged. Instead, we continue to track fish tagged in May and June of 2002 (N = 40). Those fish were tagged with transmitters with an estimated tag life of two years, which should continue to operate until the completion of this study period (31 March 2004). • Based on current telemetry data there are seven tagged bull trout in the mainstem Columbia River, four in the Wenatchee River basin, 15 in the Entiat River basin, eight in the Methow River basin, and six transmitters have been recovered (Table 1). -

Technical Report 2007-Draft

Technical Report 2013-3 __________________________________________________________________ ADULT PACIFIC LAMPREY MIGRATION IN THE LOWER COLUMBIA RIVER: 2012 HALF-DUPLEX PIT TAG STUDIES A Report for Study Code ADS-P-00-8 by M. L. Keefer, C. C. Caudill, E. L. Johnson, T. S. Clabough, M. A. Jepson, C. T. Boggs Department of Fish and Wildlife Sciences University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844-1136 and S. C. Corbett & M. L. Moser Northwest Fisheries Science Center, NOAA Fisheries 2725 Montlake Blvd. East, Seattle, WA 98112 For U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Portland District, Portland OR 2013 Technical Report 2013-3 ADULT PACIFIC LAMPREY MIGRATION IN THE LOWER COLUMBIA RIVER: 2012 HALF DUPLEX PIT-TAG STUDIES A Report for Study Code ADS-P-00-8 by M. L. Keefer, C. C. Caudill, E. L. Johnson, T. S. Clabough, M. A. Jepson, C. T. Boggs Department of Fish and Wildlife Sciences University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844-1136 and S. C. Corbett & M. L. Moser Northwest Fisheries Science Center, NOAA Fisheries 2725 Montlake Blvd. East, Seattle, WA 98112 For U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Portland and Walla Walla Districts 2013 ii Acknowledgements Many people assisted with the field work and data compilation for this report and its successful completion was made possible through their efforts. Dennis Quaempts, Carl Schilt and Chris Noyes were responsible for collecting and tagging lampreys. Travis Dick assisted with the maintenance and downloading of the monitoring equipment. Staff at other agencies also provided lamprey detection data, including Matt Fox and Cyndi Baker (Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon), Rod O’Connor (Blueleaf Environmental for Grant County Public Utility District), and Jeff Osborn (Chelan County Public Utility District). -

Passage Route Survival and Behavior of Juvenile Salmon at Priest Rapids Dam, Columbia River, WA Kyle B

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks at Central Washington University Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU Electronic Theses Student Scholarship and Creative Works Fall 2015 Passage Route Survival and Behavior of Juvenile Salmon at Priest Rapids Dam, Columbia River, WA Kyle B. Hatch Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Recommended Citation Hatch, Kyle B., "Passage Route Survival and Behavior of Juvenile Salmon at Priest Rapids Dam, Columbia River, WA" (2015). Electronic Theses. Paper 271. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Works at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. PASSAGE ROUTE SURVIVAL AND BEHAVIOR OF JUVENILE SALMON AT PRIEST RAPIDS DAM, COLUMBIA RIVER, WA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Biology by Kyle Barrett Hatch November 2015 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Kyle Barrett Hatch Candidate for the degree of Master of Science APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Clay Arango, Committee Chair ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Alison Scoville ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Paul James ______________ _________________________________________ Dean of Graduate Studies ii ABSTRACT PASSAGE ROUTE SURVIVAL AND BEHAVIOR OF JUVENILE SALMON AT PRIEST RAPIDS DAM, COLUMBIA RIVER, WA by Kyle Barrett Hatch November 2015 Columbia River hydropower is an economic mainstay of the Pacific Northwest. -

A Study of Apparent Losses of Chinook Salmon and Steelhead

A STUDY OF APPARENT LOSSES OF CHINOOK SALMON AND STEELHEAD BASED ON COUNT DISCREPANCIES BETWEEN DAMS ON THE COLUMBIA AND SNAKE RIVERS, 1967-1968 by Lowell C. Stuehrenberg Kenneth L. Liscom and Gerald E. Monan Final Report of Research Financed by U. S. Army Corps of Engineers (Contract No. DACW57-67-C-0120) and NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Northwest and Alaska Fisheries Center Coastal Zone and Estuarine Studies Division 2725 Montlake Boulevard East Seattle, Washington 98112 August 1978 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................... EXPERIMENTAL SITE AND EQUIPMENT ........... FISH TRAPS AND TAGGING BARGE .......... ACOUSTIC TAGS .................. FLAGTAGS .................... MONITORS .................... TRACKING EQUIPMENT ............... GENERAL EXPERIMENTAL PLAN .............. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES ............... TRAPPING AND TAGGING .............. MONITORING ................... BOAT DRIFTING .................. GENERAL OBSERVATIONS .. 1967e............ SPRING CHINOOK SALMON .............. Bonneville to The Dalles Dams ....... McNary to Priest Rapids and Ice Harbor Dams SUMMER CHINOOK SALMON AND STEELHEAD ....... Temperature Block ............. FALLBACK ..................... GENERAL OBSERVATIONS .. 1968............. SPRING CHINOOK SALMON .............. SUMMER CHINOOK SALMON AND STEELHEAD ..............39 Temperature Block ....................43 FALLBACK ........................... 45 CONCLUSIONS .............................46 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...........................48 LITERATURE CITED ..........................-49 INTRODUCTION -

Downloaded from the DRS Website At

Quincy Chute Hydroelectric Project Wanapum Dam Seattle Spokane Grant County Potholes Priest Rapids East Canal Dam Headworks Nine Canyon Wind Farm WANAPUM DAM QUINCY CHUTE HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT Generation Units . 10. Rated Capacity . 1,203.6. MW Rated Capacity . 9.4. MW Concrete/Earthfill Length . 8,637. FT First Power Generation . .1985 Rated Head . 80 FT Construction Started . .1959 First Power Generation . .1963 POTHOLES EAST CANAL HEADWORKS PROJECT PRIEST RAPIDS DAM Rated Capacity . 6.5. MW First Power Generation . .1990 Generation Units . 10. Rated Capacity . 950. MW Concrete/Earthfill Length . 10,103. FT NINE CANYON WIND PROJECT Rated Head . 78 FT Construction Started . .1956 12 .5% of Project Peak Capacity . .12 MW First Power Generation . .1959 First Power Generation . .2003 ELECTRIC SYSTEM Overhead Distribution Lines . 2,795 MILES Underground Distribution Lines . 1,102. MILES Overhead Transformers . .24,477 Padmount Transformers . 9,935 115kV Transmission Lines . 282. MILES 230kV Transmission Lines . 202. MILES ACTIVE METERS Residential . 39,103. Irrigation . 5,193 Industrial . 122 Commercial . 7,248 Large Commercial . 107 Street Light and Other . .439 Total Active Meters . 52,212. SUBSTATIONS Distribution . 49 Transmission . 5. Transmission/Distribution . 3. HIGH SPEED NETWORK Customers with fiber-optic availability . .33,149 Customers using fiber-optic service . 19,043 Customers using wireless service . 290 As of Dec. 31, 2019 Grant PUD was established by local residents in 1938 to provide power service to all of the county’s residents. We honor the resolve of our founders through our guiding vision, mission and values. VISION Excellence in service and leadership. We continually ask how we can improve service quality, reliability and stewardship of our resources in the most cost-effective manner . -

Characterization of Gatewell Orifice Lighting at the Bonneville Dam Second Powerhouse and Compendium of Research on Light Guidance with Juvenile Salmonids

PNNL-17210 Characterization of Gatewell Orifice Lighting at the Bonneville Dam Second Powerhouse and Compendium of Research on Light Guidance with Juvenile Salmonids FINAL REPORT RP Mueller MA Simmons September 2008 PNNL-17210 Characterization of Gatewell Orifice Lighting at the Bonneville Dam Second Powerhouse and Compendium of Research on Light Guidance with Juvenile Salmonids Final Report RP Mueller MA Simmons September 2008 Prepared for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Portland District, under a Government Order with the U.S. Department of Energy Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Richland, Washington 99352 Summary The study described in this report was conducted by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) to provide biologist and engineers of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) with general design guidelines for using artificial lighting to enhance the passage of juvenile salmonids into the collection channel at the Bonneville Dam second powerhouse, managed by the USACE Portland District. The work comprised three primary objectives. The first was to review and synthesize all relevant studies in which artificial light was evaluated in a field or laboratory setting for its potential to guide fish at passage barriers within juvenile salmonid outmigration corridors. The second objective was to conduct a field study at the Bonneville Dam second powerhouse to evaluate the output levels of two artificial light sources at one orifice entrance within Gatewell 12. The third objective was to compare, in a laboratory setting, the performance of three light sources in terms of light intensity values. PNNL reviewed 36 sources in the published gray and peer-reviewed literature and prepared a synopsis that includes the study objectives, species and life stage, experimental conditions, type of lighting used, and a summary of the results. -

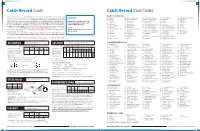

Catch Record Cards & Codes

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142.