Report on the Route of Migration from Myanmar and Cambodia to Thailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

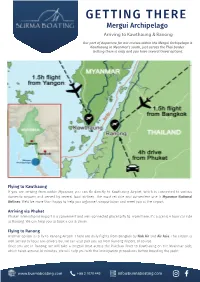

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong Our port of departure for our cruises within the Mergui Archipelago is Kawthaung in Myanmar’s south, just across the Thai border. Getting there is easy and you have several travel options. Flying to Kawthaung If you are arriving from within Myanmar, you can fly directly to Kawthaung Airport, which is connected to various domestic airports and served by several local airlines. The most reliable and convenient one is Myanmar National Airlines. We’d be more than happy to help you organise transportation and meet you at the airport. Arriving via Phuket Phuket International Airport is a convenient and well-connected place to fly to. From there, it’s a scenic 4 hour car ride to Ranong. We can help you to book a car & driver. Flying to Ranong Another option is to fly to Ranong Airport. There are daily flights from Bangkok by Nok Air and Air Asia. The airport is well served by local taxi drivers but we can also pick you up from Ranong Airport, of course. Once you are in Ranong, we will take a longtail boat across the Pakchan River to Kawthaung on the Myanmar side, which takes around 30 minutes. We will help you with the immigration procedures before boarding the yacht. www.burmaboating.com +66 2 1070 445 [email protected] GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Crossing the Thai-Myanmar border In the case you arrive through the Thailand side and doesn’t want our assistance, here is a quick step by step instruction to cross the border between the 2 countries. -

ACU's Thai-Burma Program

ACU’s Thai-Burma Program: Engagement with the Myanmar refugee crisis Duncan Cooka and Michael Ondaatjeb a Academic Lead, Thai-Burma Program b Pro Vice-Chancellor (Arts and Academic Culture) National School of Arts, Australian Catholic University Paper presented at The ACU and DePaul University conference on community engagement and service learning. Tuesday 23 July, 2019 Introduction to ACU’s Thai-Burma Program Introduction video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dtvaXe2GYrQ 2 | Faculty of Education and Arts The East Myanmar-Thailand context • Myanmar (formerly Burma) • Approx. 6000 km northwest of Australia • Population: Approx. 54 million Thailand • At least 135 distinct ethnic groups • Land borders with Bangladesh, India, China, Laos and Thailand Myanmar 3 | Faculty of Education and Arts Historical/Political context of the refugee crisis • Thai-My border refugees since 1984 • Conflict dates back to at least 1949 • Longest running civil war in the world • Multiple East Myanmar ethnic groups fleeing armed conflict and persecution for three decades: Karen, Karenni, Mon and Shan, but others as well • ‘Slow genocide’ of ethnic minorities • Human rights violations by Burmese government • 2011: military-regime to a military-controlled government 4 | Faculty of Education and Arts The Thai-Myanmar Border context • Approx. 100,000 refugees in 9 camps in TL • Largest camp: Mae La, c. 36,000 people • Thailand: no national asylum systems, refugees often considered illegal migrants • No organised access to Thai education system • ACU’s operations -

Chapter 2 Leterature Review

CHAPTER 2 LETERATURE REVIEW The contents in this chapter were divided into five parts as follows: 1. Data from Aranyaprathet Customs House 2. A description of Ban Klongluek Border Market 3. Stressor 4. Stress 4.1 Definition of stress 4.2 The concept of stress 4.3 Stress evaluation 4.4 Stress related outcomes 5. Stress management 5.1 The concept of coping 5.2 The concept of stress management Data from Aranyaprathet Customs House The data from Information and Communication Technology, by the cooperation of Thailand Custom House indicates that overall business on the borderland of Thailand have increased every year by millions of baht since 1997. Comparison between all Thailand -Cambodia business shows borderland International business is 75% of all International business between Thailand and Cambodia as show table 2-1. Borderland businesses are mainstays of economy in this area of country. Sakaeo Province is an eastern province of Thailand where has the boundary contacts with the Cambodia. In 2007, Aranyaprathet Custom House and Chanthaburi Custom House had total trade value 18,468 and 14,432 million baht, respectively. This market has a lot of tourists, about 10,000 persons per day, circulating funds of about 100-200 million baht as show table 2-2 and table 2-3. 10 Table 2-1 Comparison between International business is Thailand-Cambodia business and Thailand -Cambodia business borderland (1997-2007) Year International Border Line Amount* % Amount* % 1997 11,825 100 8,271 70 1998 13,413 100 10,041 75 1999 13,939 100 10,496 75 2000 14,230 -

An Updated Checklist of Aquatic Plants of Myanmar and Thailand

Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Taxonomic paper An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand Yu Ito†, Anders S. Barfod‡ † University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand ‡ Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark Corresponding author: Yu Ito ([email protected]) Academic editor: Quentin Groom Received: 04 Nov 2013 | Accepted: 29 Dec 2013 | Published: 06 Jan 2014 Citation: Ito Y, Barfod A (2014) An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand. Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Abstract The flora of Tropical Asia is among the richest in the world, yet the actual diversity is estimated to be much higher than previously reported. Myanmar and Thailand are adjacent countries that together occupy more than the half the area of continental Tropical Asia. This geographic area is diverse ecologically, ranging from cool-temperate to tropical climates, and includes from coast, rainforests and high mountain elevations. An updated checklist of aquatic plants, which includes 78 species in 44 genera from 24 families, are presented based on floristic works. This number includes seven species, that have never been listed in the previous floras and checklists. The species (excluding non-indigenous taxa) were categorized by five geographic groups with the exception of to reflect the rich diversity of the countries' floras. Keywords Aquatic plants, flora, Myanmar, Thailand © Ito Y, Barfod A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Cross-Border Cooperation Case Study of Cambodia-Vietnam Border Point

Cross-border Cooperation Case Study of Cambodia-Vietnam Border Point The 3rd Global Roundtable on Infrastructure Governance and Tools 24 May 2019 Seoul Kazumasa Sanui J I C A Chief Advisor Project for Improving Logistics System of Cambodia Cross-border Cooperation Contents Case Study of Cambodia-Vietnam Border Point 1. Characteristics of cross-border cooperation * 2. Introduction of the project 3. Preparation for the project 4. Critical challenges and lessons learned for cross-border cooperation * * Here, this presentation tries to extract common factors from the case study. Japan International Cooperation Agency 1 1. Characteristics of cross-border cooperation Cross-border cooperation projects commonly… • Have many stakeholders. • Require lengthy coordination process. • Are affected by state-state power balance. • Are unlikely to solve only by the countries concerned. • Are sometimes controversial, even though having reached agreement by countries concerned. Japan International Cooperation Agency 2 2. Introduction of the project OVERALL GOAL To strengthen connectivity between Cambodia and Vietnam through Southern Economic Corridor OBJECTIVE To reduce time and improve reliability for border-crossing at Bavet – Moc Bai TARGET COUNTRY Cambodia and Vietnam PERIOD 2018 – (preparatory stage) MODALITY Technical assistance, Loan (TBC) BACKGROUND AGREEMENTS Cross-border Transport Agreement in Greater Mekong Subregion, Bilateral agreements, MOU for expressway Japan International Cooperation Agency 3 Southern Economic Corridor (SEC) Features of -

Military Brotherhood Between Thailand and Myanmar: from Ruling to Governing the Borderlands

1 Military Brotherhood between Thailand and Myanmar: From Ruling to Governing the Borderlands Naruemon Thabchumphon, Carl Middleton, Zaw Aung, Surada Chundasutathanakul, and Fransiskus Adrian Tarmedi1, 2 Paper presented at the 4th Conference of the Asian Borderlands Research Network conference “Activated Borders: Re-openings, Ruptures and Relationships”, 8-10 December 2014 Southeast Asia Research Centre, City University of Hong Kong 1. Introduction Signaling a new phase of cooperation between Thailand and Myanmar, on 9 October 2014, Thailand’s new Prime Minister, General Prayuth Chan-o-cha took a two-day trip to Myanmar where he met with high-ranked officials in the capital Nay Pi Taw, including President Thein Sein. That this was Prime Minister Prayuth’s first overseas visit since becoming Prime Minister underscored the significance of Thailand’s relationship with Myanmar. During their meeting, Prime Minister Prayuth and President Thein Sein agreed to better regulate border areas and deepen their cooperation on border related issues, including on illicit drugs, formal and illegal migrant labor, including how to more efficiently regulate labor and make Myanmar migrant registration processes more efficient in Thailand, human trafficking, and plans to develop economic zones along border areas – for example, in Mae 3 Sot district of Tak province - to boost trade, investment and create jobs in the areas . With a stated goal of facilitating border trade, 3 pairs of adjacent provinces were named as “sister provinces” under Memorandums of Understanding between Myanmar and Thailand signed by the respective Provincial governors during the trip.4 Sharing more than 2000 kilometer of border, both leaders reportedly understood these issues as “partnership matters for security and development” (Bangkok Post, 2014). -

Transport Logistics

MYANMAR TRADE FACILITATION THROUGH LOGISTCS CONNECTIVITY HLA HLA YEE BITEC , BANGKOK 4.9.15 [email protected] Total land area 677,000sq km Total length (South to North) 2,100km (East to West) 925km Total land boundaries 5,867km China 2,185km Lao 235km Thailand 1,800km Bangladesh 193km India 1,463km Total length of coastline 2,228km Capital : Naypyitaw Language :Myanmar MYANMAR IN 2015 REFORM & FAST ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS SIGNIFICANT POTENTIAL CREDIBILITY AMONG ASEAN NATIONS GATE WAY “ CHINA & INDIA & ASEAN” MAXIMIZING MULTIMODALTRANSPORT LINKAGES EXPEND GMS ECONOMIC TRANSPORT CORRIDORS EFFECTIVE EXTENSION INTO MYANMAR INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTION TRADE AND LOTISGICS SUPPLY CHAIN TRANSPARENCY & PREDICTABILITY LEGAL & REGULATORY FREAMEWORK INFRASTUCTURE INFORMATION CORRUPTION FIANACIAL SERVICE “STRENGTHEING SME LOGISTICS” INDUSTRIAL ZONE DEVELOPMENT 7 NEW IZ KYAUk PHYU Yadanarbon(MDY) SEZ Tart Kon (NPD) Nan oon Pa han 18 Myawadi Three pagoda Existing IZ Pon nar island Yangon(4) Mandalay Meikthilar Myingyan Yenangyaing THI LA WAR Pakokku SEZ Monywa Pyay Pathein DAWEI Myangmya SEZ Hinthada Mawlamyaing Myeik Taunggyi Kalay INDUSTRIES CATEGORIES Competitive Industries Potential Industries Basic Industries Food and Beverages Automobile Parts Agricultural Machinery Garment & Textile Industrial Materials Agricultural Fertilizer Household Woodwork Minerals & Crude Oil Machinery & spare parts Gems & Jewelry Pharmaceutical Electrical & Electronics Construction Materials Paper & Publishing Renewable Energy Household products TRANSPORT -

Smallholders and Forest Landscape Restoration in Upland Northern Thailand

102 International Forestry Review Vol.19(S4), 2017 Smallholders and forest landscape restoration in upland northern Thailand A. VIRAPONGSEa,b aMiddle Path EcoSolutions, Boulder, CO 80301, USA bThe Ronin Institute, Montclair, NJ 07043, USA Email: [email protected] SUMMARY Forest landscape restoration (FLR) considers forests as integrated social, environmental and economic landscapes, and emphasizes the produc- tion of multiple benefits from forests and participatory engagement of stakeholders in FLR planning and implementation. To help inform application of the FLR approach in upland northern Thailand, this study reviews the political and historical context of forest and land manage- ment, and the role of smallholders in forest landscape management and restoration in upland northern Thailand. Data were collected through a literature review, interviews with 26 key stakeholders, and three case studies. Overall, Thai policies on socioeconomics, forests, land use, and agriculture are designed to minimize smallholders’ impact on natural resources, although more participatory processes for land and forest management (e.g. community forests) have been gaining some traction. To enhance the potential for FLR success, collaboration processes among upland forest stakeholders (government, NGOs, industry, ethnic minority smallholders, lowland smallholders) must be advanced, such as through innovative communication strategies, integration of knowledge systems, and most importantly, by recognizing smallholders as legitimate users of upland forests. Keywords: North Thailand, smallholders, forest management, upland, land use Politique forestière et utilisation de la terre par petits exploitants dans les terres hautes de la Thaïlande du nord A. VIRAPONGSE Cette étude cherche à comprendre le contexte politique de la gestion forestière dans les terres hautes de la Thaïlande du nord, et l’expérience qu’ont les petits exploitants de ces politiques. -

The Transport Trend of Thailand and Malaysia

Executive Summary Report The Potential Assessment and Readiness of Transport Infrastructure and Services in Thailand for ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Content Page 1. Introduction 1.1 Rationales 1 1.2 Objectives of Study 1 1.3 Scopes of Study 2 1.4 Methodology of Study 4 2. Current Status of Thailand Transport System in Line with Transport Agreement of ASEAN Community 2.1 Master Plan and Agreement on Transport System in ASEAN 5 2.2 Major Transport Systems for ASEAN Economic Community 7 2.2.1 ASEAN Highway Network 7 2.2.2 Major Railway Network for ASEAN Economic Community 9 2.2.3 Main Land Border Passes for ASEAN Economic Community 10 2.2.4 Main Ports for ASEAN Economic Community 11 2.2.5 Main Airports for ASEAN Economic Community 12 2.3 Efficiency of Current Transport System for ASEAN Economic Community 12 3. Performance of Thailand Economy and Transport Trend after the Beginning of ASEAN Economic Community 3.1 Factors Affecting Cross-Border Trade and Transit 14 3.2 Economic Development for Production Base Thriving in Thailand 15 3.2.1 The analysis of International Economic and Trade of Thailand and ASEAN 15 3.2.2 Major Production Bases and Commodity Flow of Prospect Products 16 3.2.3 Selection of Potential Industries to be the Common Production Bases of Thailand 17 and ASEAN 3.2.4 Current Situation of Targeted Industries 18 3.2.5 Linkage of Targeted Industries at Border Areas, Important Production Bases, 19 and Inner Domestic Areas TransConsult Co., Ltd. King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi 2T Consulting and Management Co., Ltd. -

Charlie Thame and Kraiyos Patrawart February 2017

Charlie Thame and Kraiyos Patrawart February 2017 Strengthening Out of School Children (OOSC) Mechanisms in Tak Province (February 2017) Charlie Thame and Kraiyos Patrawart ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Cover photo by Kantamat Palawat Published by This report was written by Charlie Thame and Kraiyos Patrawart. Both would like to thank Save the Children Thailand all those who contributed to the project, which would not have been possible without the kind 14th Fl., Maneeya Center Building (South), 518/5 Ploenchit Road, support of several individuals and organisations. Special thanks are extended to the Primary Lumpini, Pathumwan, Bangkok 10330, Thailand Education Service Area Office Tak 2 (PESAO Tak 2), Tak Province. Khun Pongsakorn, Khun +66(0) 2684 1286 Aof, and Khun Ninarall graciously gave their time and support to the team, without which the [email protected] study would not have been possible. Aarju Hamal and Sia Kukuawkasem provided invaluable http://thailand.savethechildren.net research assistance with documentary review, management and coordination, and translation. Siraporn Kaewsombat’s assistance was also crucial for the success of the project. The team would like to express further thanks to all at Save the Children Thailand for their support during the study, particularly Tim Murray and Kate McDermott. REACT The Reaching Education for All Children in Thailand (REACT) project is supported by Save the Children Hong Kong and implemented by Save the Children International in Thailand. REACT aims to ensure migrant children in Thailand have access to quality basic education and communities support children’s learning. The main target groups are the migrant children in Tak and Ranong provinces. -

Cross-Border Migration, Trafficking and the Sex Industry: Thailand and Its Neighbours

86 Articles Section Cross-Border Migration, Trafficking and the Sex Industry: Thailand and Its Neighbours Carl Grundy-Warr, Rita King and Gary Risser The post-Cold War formalisation of cross-border • the so-called transitional economies of political and economic relations has turned Indochina and Myanmar (Burma) have been previously alienated borderlands into coexistent, opened up to international capital; even interdependent ones, such that each state tries to maximise economic advantage through more • there is a need for more migrant labour to feed open borders (Grundy-Warr, 1993).1 One dimension the economic growth of the emerging Newly of these new geopolitical realities is the promotion Industrialising Economies (NIEs) of Asia; of transboundary transportation networks, the so called ‘corridors of growth’ linking various parts of • there are problems of deteriorating economies the greater Mekong Basin together as a means to in the countryside, particularly in Myanmar and encourage closer intra-regional trade and Cambodia. Poverty is a critical issue underlying investments (Walker, 1993). The Asian the migration of young people from villages to Development Bank has effectively become a towns or to other countries; supranational investment broker supporting ambitious transboundary infrastructural projects • the end of the Cold War politics and growth in which is in line with the Bank’s vision of sub- formal trade has also produced a big expansion regional economic cooperation (Chapman, 1995). in cross-border natural resource exploitation, -

East-West Economic Corridor (EWEC)Strategy and Action Plan

Munich Personal RePEc Archive East-West Economic Corridor (EWEC)Strategy and Action Plan Lord, Montague ADB, Asian Development Bank May 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/41147/ MPRA Paper No. 41147, posted 09 Sep 2012 18:18 UTC East-West Economic Corridor (EWEC) Strategy and Action Plan RETA-6310 Development Study of the East-West Economic Corridor Greater Mekong Subregion Prepared by Montague Lord Presented to Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 0401 Metro Manila The Philippines May 2009 RETA 6310: EWEC STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................. iv List of Tables, Figures and Box ................................................................................................................ vi Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... viii Map ................................................................................................................................................ xi 1. Background and Accomplishments .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Overview of the Corridor Area ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 First Strategy and Action Plan, 2001-2008 .............................................................................