Montane Oak–Hickory Forest (Acidic Subtype)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

Native Nebraska Woody Plants

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS NATIVE NEBRASKA WOODY PLANTS Trees (Genus/Species – Common Name) 62. Atriplex canescens - four-wing saltbrush 1. Acer glabrum - Rocky Mountain maple 63. Atriplex nuttallii - moundscale 2. Acer negundo - boxelder maple 64. Ceanothus americanus - New Jersey tea 3. Acer saccharinum - silver maple 65. Ceanothus herbaceous - inland ceanothus 4. Aesculus glabra - Ohio buckeye 66. Cephalanthus occidentalis - buttonbush 5. Asimina triloba - pawpaw 67. Cercocarpus montanus - mountain mahogany 6. Betula occidentalis - water birch 68. Chrysothamnus nauseosus - rabbitbrush 7. Betula papyrifera - paper birch 69. Chrysothamnus parryi - parry rabbitbrush 8. Carya cordiformis - bitternut hickory 70. Cornus amomum - silky (pale) dogwood 9. Carya ovata - shagbark hickory 71. Cornus drummondii - roughleaf dogwood 10. Celtis occidentalis - hackberry 72. Cornus racemosa - gray dogwood 11. Cercis canadensis - eastern redbud 73. Cornus sericea - red-stem (redosier) dogwood 12. Crataegus mollis - downy hawthorn 74. Corylus americana - American hazelnut 13. Crataegus succulenta - succulent hawthorn 75. Euonymus atropurpureus - eastern wahoo 14. Fraxinus americana - white ash 76. Juniperus communis - common juniper 15. Fraxinus pennsylvanica - green ash 77. Juniperus horizontalis - creeping juniper 16. Gleditsia triacanthos - honeylocust 78. Mahonia repens - creeping mahonia 17. Gymnocladus dioicus - Kentucky coffeetree 79. Physocarpus opulifolius - ninebark 18. Juglans nigra - black walnut 80. Prunus besseyi - western sandcherry 19. Juniperus scopulorum - Rocky Mountain juniper 81. Rhamnus lanceolata - lanceleaf buckthorn 20. Juniperus virginiana - eastern redcedar 82. Rhus aromatica - fragrant sumac 21. Malus ioensis - wild crabapple 83. Rhus copallina - flameleaf (shining) sumac 22. Morus rubra - red mulberry 84. Rhus glabra - smooth sumac 23. Ostrya virginiana - hophornbeam (ironwood) 85. Rhus trilobata - skunkbush sumac 24. Pinus flexilis - limber pine 86. Ribes americanum - wild black currant 25. -

Go Nuts! P2 President’S Trees Display Fall Glory in a ‘Nutritious’ Way Report by Lisa Lofland Gould P4 Pollinators & Native Plants UTS HAVE Always Fascinated N Me

NEWSLETTER OF THE NC NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY Native Plant News Fall 2020 Julie Higgie, editor Vol. 18, Issue 3 INSIDE: Go Nuts! P2 President’s Trees Display Fall Glory in a ‘NUTritious’ Way Report By Lisa Lofland Gould P4 Pollinators & Native Plants UTS HAVE always fascinated N me. I was a squirrel for a while when I P6 Book Review was around six years old. My best friend and I spent hours under an oak tree in a P10 Habitat Report neighbor’s yard one autumn, amassing piles of acorns and dashing from imagined preda- P12 Society News tors. So, it seems I’ve always known there’s P14 Scholar News nothing like a good stash of nuts to feel ready for winter. P16 Member It’s not surprising that a big nut supply might leave a winter-conscious Spotlight beast feeling smug. Nuts provide fats, protein, carbohydrates, and vit- amins, along with a number of essential elements such as copper, MISSION zinc, potassium, and manganese. There is a great deal of food value STATEMENT: in those little packages! All that compactly bundled energy evolved to give the embryo plenty of time to develop; the nut’s worth to foraging Our mission is to animals assures that the fruit is widely dispersed. Nut trees pay a promote the en- price for the dispersal work of the animals, but apparently enough sur- vive to make it worth the trees’ efforts: animals eat the nuts and even joyment and con- bury them in storage, but not all are retrieved, and those that the servation of squirrels forget may live to become the mighty denizens of our forests. -

Species List For: Engelmann Woods NA 174 Species

Species List for: Engelmann Woods NA 174 Species Franklin County Date Participants Location NA List NA Nomination List List made by Maupin and Kurz, 9/9/80, and 4/21/93 WGNSS Lists Webster Groves Nature Study Society Fieldtrip Participants WGNSS Vascular Plant List maintained by Steve Turner Species Name (Synonym) Common Name Family COFC COFW Acalypha virginica Virginia copperleaf Euphorbiaceae 2 3 Acer negundo var. undetermined box elder Sapindaceae 1 0 Acer saccharum var. undetermined sugar maple Sapindaceae 5 3 Achillea millefolium yarrow Asteraceae/Anthemideae 1 3 Actaea pachypoda white baneberry Ranunculaceae 8 5 Adiantum pedatum var. pedatum northern maidenhair fern Pteridaceae Fern/Ally 6 1 Agastache nepetoides yellow giant hyssop Lamiaceae 4 3 Ageratina altissima var. altissima (Eupatorium rugosum) white snakeroot Asteraceae/Eupatorieae 2 3 Agrimonia rostellata woodland agrimony Rosaceae 4 3 Ambrosia artemisiifolia common ragweed Asteraceae/Heliantheae 0 3 Ambrosia trifida giant ragweed Asteraceae/Heliantheae 0 -1 Amelanchier arborea var. arborea downy serviceberry Rosaceae 6 3 Antennaria parlinii var. undetermined (A. plantaginifolia) plainleaf pussytoes Asteraceae/Gnaphalieae 5 5 Aplectrum hyemale putty root Orchidaceae 8 1 Aquilegia canadensis columbine Ranunculaceae 6 1 Arisaema triphyllum ssp. triphyllum (A. atrorubens) Jack-in-the-pulpit Araceae 6 -2 Aristolochia serpentaria Virginia snakeroot Aristolochiaceae 6 5 Arnoglossum atriplicifolium (Cacalia atriplicifolia) pale Indian plantain Asteraceae/Senecioneae 4 5 Arnoglossum reniforme (Cacalia muhlenbergii) great Indian plantain Asteraceae/Senecioneae 8 5 Asarum canadense wild ginger Aristolochiaceae 6 5 Asclepias quadrifolia whorled milkweed Asclepiadaceae 6 5 Asimina triloba pawpaw Annonaceae 5 0 Asplenium rhizophyllum (Camptosorus) walking fern Aspleniaceae Fern/Ally 7 5 Asplenium trichomanes ssp. trichomanes maidenhair spleenwort Aspleniaceae Fern/Ally 9 5 Srank: SU Grank: G? * Barbarea vulgaris yellow rocket Brassicaceae 0 0 Blephilia hirsuta var. -

Black Oak Quercus Velutina Tree Acorns ILLINOIS RANGE

black oak Quercus velutina Kingdom: Plantae FEATURES Division: Magnoliphyta The deciduous black oak tree may grow to a height Class: Magnoliopsida of 80 feet and a diameter of about three and one- Order: Fagales half feet. The trunk is straight. The bark is black and deeply furrowed, with a yellow or orange inner bark. Family: Fagaceae The leaves are arranged alternately on the stem. The ILLINOIS STATUS simple leaf blade has seven to nine shallow lobes, each lobe bristle-tipped. The leaf is dark green, shiny common, native and smooth on the upper surface. It is hairy all over or hairy only along the veins on the lower surface. Each leaf may be 10 inches long and eight inches wide with a five-inch leafstalk. Male and female flowers are separate but located on the same tree. The tiny flower has no petals. Male (staminate) flowers are arranged in drooping clusters, while female (pistillate) flowers are in groups of one to four. The fruit is an acorn. Acorns may be single or in groups of two. The acorn is red-brown, ovoid or ellipsoid and not more than one-half enclosed by the cup. The cup appears to have a ragged edge. BEHAVIORS The black oak may be found statewide in Illinois. This tree grows in upland woods. It flowers in April tree and May when the leaves begin to unfold. The hard, red-brown wood is used in construction, for fuel and ILLINOIS RANGE for making fence posts.. acorns © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

Introduction to the Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan

SOUTHERN BLUE RIDGE ECOREGIONAL CONSERVATION PLAN Summary and Implementation Document March 2000 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY and the SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN FOREST COALITION Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan Summary and Implementation Document Citation: The Nature Conservancy and Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition. 2000. Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan: Summary and Implementation Document. The Nature Conservancy: Durham, North Carolina. This document was produced in partnership by the following three conservation organizations: The Nature Conservancy is a nonprofit conservation organization with the mission to preserve plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition is a nonprofit organization that works to preserve, protect, and pass on the irreplaceable heritage of the region’s National Forests and mountain landscapes. The Association for Biodiversity Information is an organization dedicated to providing information for protecting the diversity of life on Earth. ABI is an independent nonprofit organization created in collaboration with the Network of Natural Heritage Programs and Conservation Data Centers and The Nature Conservancy, and is a leading source of reliable information on species and ecosystems for use in conservation and land use planning. Photocredits: Robert D. Sutter, The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This first iteration of an ecoregional plan for the Southern Blue Ridge is a compendium of hypotheses on how to conserve species nearest extinction, rare and common natural communities and the rich and diverse biodiversity in the ecoregion. The plan identifies a portfolio of sites that is a vision for conservation action, enabling practitioners to set priorities among sites and develop site-specific and multi-site conservation strategies. -

Checklist Trees

Willow Linden, Dogwood Trees Serviceberry / Sarvis V American Basswood S Amelanchier arborea Tilia americana Checklist Cockspur Hawthorn W, O Rough-leaved Dogwood V Crataegus crus-galli Cornus drummondii Chickasaw Plum W, O Flowering Dogwood V Prunus angustifolia Cornus florida Big Tree Plum W Tupelo, Ebony Prunus mexicana Black Cherry V Black Gum V Prunus serotina Nyssa sylvatica var. sylvatica Pea Persimmon O Diospyros virginiana Redbud V Ash Cercis canadensis Honey Locust V White Ash M Gleditsia triancanthos Fraxinus americana Black Locust V Blue Ash S, B Robinia pseudo-acacia Fraxinus quadrangualta Cashew Invasive Non-Native Smooth Sumac V Mimosa / Silktree V Rhus glabra Albizia julibrissin Maple Tree of Heaven V Ailanthus altissima Box Elder L, Buffalo National River Acer negundo Red Maple L, Acer rubrum var. rubrum Sugar Maple M Acer saccharum var. saccharum Walnut, Birch Elm, Mulberry, Magnolia The rugged region of the Buffalo national River contains over one hundred different species of Shagbark Hickory M Sugarberry V trees and shrubs. The park trails offer some of Carya ovata Celtis laevigata the best places for viewing native trees and shrubs. This checklist highlights the more Black Hickory V Hackberry V Carya texana Celtis occidentalis Mockernut Hickory V Winged Elm V Habitat Key Carya tomentosa Ulmus alata The following symbols have been Black Walnut V American Elm M used to indicatethetype of habitat Juglans nigra Ulmus americana where trees and shrubs can be found. River Birch S Slippery Elm V Betula nigra Ulmus rubra W - Woodlands B - Bluffs / dry areas / glades Iron wood S, M Osage Orange V S - Streams /swampy areas Carpinus caroliniana Maclura pomifera M - Moist soil L - Lowlands Beech, Oaks Red Mulberry M Morus rubra U - Uplands Ozark Chinquapin V O - Open areas / fields Castanea pumila var. -

Native Tree Families, Including Large and Small Trees, 1/1/08 in the Southern Blue Ridge Region (Compiled by Rob Messick Using Three Sources Listed Below.)

Native Tree Families, Including Large and Small Trees, 1/1/08 in the Southern Blue Ridge Region (Compiled by Rob Messick using three sources listed below.) • Total number of tree families listed in the southern Blue Ridge region = 33. • Total number of native large and small tree species listed = 113. (Only 84 according to J. B. & D. L..) There are 94 tree species in more frequently encountered families. There are 19 tree species in less frequently encountered families. • There is 93 % compatibility between Ashe & Ayers (1902), Little (1980), and Swanson (1994). (W. W. Ashe lists 105 tree species in the region in 1902. These are fully compatible with current listings.) ▸means more frequently encountered species. ?? = means a tree species that possibly occurs in the region, though its presence is not clear. More frequently encountered tree families (21): Pine Family Cashew Family Walnut Family Holly Family Birch Family Maple Family Beech Family Horse-chestnut (Buckeye) Family Magnolia Family Linden (Basswood) Family Laurel Family Tupelo-gum Family Witch-hazel Family Dogwood Family Plane-tree (Sycamore) Family Heath Family Rose Family Ebony Family Legume Family Storax (Snowbell) Family Olive Family Less frequently encountered tree families (12): Cypress Family Bladdernut Family Willow Family Buckthorn Family Elm Family Tea Family Mulberry Family Ginseng Family Custard-apple (Annona) Family Sweetleaf Family Rue Family Honeysuckle Family ______________________________________________________________________________ • More Frequently Encountered Tree Families: Pine Family (10): ▸ Fraser fir - Abies fraseri (a.k.a. Balsam) ▸ red spruce - Picea rubens ▸ shortleaf pine - Pinus echinata ▸ table mountain pine - Pinus pungens ▸ pitch pine - Pinus rigida ▸ white pine - Pinus strobus ▸ Virginia pine - Pinus virginiana loblolly pine - Pinus taeda ▸ eastern hemlock - Tsuga canadensis (a.k.a. -

Pignut Hickory

Carya glabra (Mill.) Sweet Pignut Hickory Juglandaceae Walnut family Glendon W. Smalley Pignut hickory (Curya glabru) is a common but not -22” F) have been recorded within the range. The abundant species in the oak-hickory forest associa- growing season varies by latitude and elevation from tion in Eastern United States. Other common names 140 to 300 days. are pignut, sweet pignut, coast pignut hickory, Mean annual relative humidity ranges from 70 to smoothbark hickory, swamp hickory, and broom hick- 80 percent with small monthly differences; daytime ory. The pear-shaped nut ripens in September and relative humidity often falls below 50 percent while October and is an important part of the diet of many nighttime humidity approaches 100 percent. wild animals. The wood is used for a variety of Mean annual hours of sunshine range from 2,200 products, including fuel for home heating. to 3,000. Average January sunshine varies from 100 to 200 hours, and July sunshine from 260 to 340 Habitat hours. Mean daily solar radiation ranges from 12.57 to 18.86 million J mf (300 to 450 langleys). In Native Range January daily radiation varies from 6.28 to 12.57 million J m+ (150 to 300 langleys), and in July from The range of pignut hickory (fig. 1) covers nearly 20.95 to 23.04 million J ti (500 to 550 langleys). all of eastern United States (11). It extends from According to one classification of climate (20), the Massachusetts and the southwest corner of New range of pignut hickory south of the Ohio River, ex- Hampshire westward through southern Vermont and cept for a small area in Florida, is designated as extreme southern Ontario to central Lower Michigan humid, mesothermal. -

TREES of OHIO Field Guide DIVISION of WILDLIFE This Booklet Is Produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife As a Free Publication

TREES OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized reproduction is pro- hibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the ODNR Division of Wildlife and its contributing artists and photographers. For additional INTRODUCTION information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE (1-800-945-3543). Forests in Ohio are diverse, with 99 different tree spe- cies documented. This field guide covers 69 of the species you are most likely to encounter across the HOW TO USE THIS BOOKLET state. We hope that this guide will help you appre- ciate this incredible part of Ohio’s natural resources. Family name Common name Scientific name Trees are a magnificent living resource. They provide DECIDUOUS FAMILY BEECH shade, beauty, clean air and water, good soil, as well MERICAN BEECH A Fagus grandifolia as shelter and food for wildlife. They also provide us with products we use every day, from firewood, lum- ber, and paper, to food items such as walnuts and maple syrup. The forest products industry generates $26.3 billion in economic activity in Ohio; however, trees contribute to much more than our economic well-being. Known for its spreading canopy and distinctive smooth LEAF: Alternate and simple with coarse serrations on FRUIT OR SEED: Fruits are composed of an outer prickly bark, American beech is a slow-growing tree found their slightly undulating margins, 2-4 inches long. Fall husk that splits open in late summer and early autumn throughout the state. -

The Demographics and Regeneration Dynamic of Hickory in Second-Growth Temperate Forest

Forest Ecology and Management 419–420 (2018) 187–196 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco The demographics and regeneration dynamic of hickory in second-growth T temperate forest ⁎ Aaron B. Leflanda, , Marlyse C. Duguida, Randall S. Morinb, Mark S. Ashtona a Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, New Haven, CT, United States b USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Newtown Square, PA, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Hickory (Carya spp.) is an economically and ecologically important genus to the eastern deciduous forest of Carya North America. Yet, much of our knowledge about the genus comes from observational and anecdotal studies Dendrochronology that examine the genus as a whole, or from research that examines only one species, in only one part of its range. Forest inventory Here, we use data sets from three different spatial scales to determine the demographics and regeneration Landscape patterns of the four most abundant hickory species in the Northeastern United States. These species were the New York shagbark (C. ovata), pignut (C. glabra), mockernut (C. tomentosa), and bitternut (C. cordiformis) hickories. We New England Oak-hickory examine trends in hickory demographics, age class and structure at the regional scale (New England and New Silviculture York), the landscape scale (a 3000 ha forest in northwestern Connecticut) and at the stand scale (0.25–5 ha). Our analysis at all three scales show that individual hickory species are site specific with clumped distribution patterns associated with climate and geology at regional scales; and with soil moisture and fertility at landscape scales. -

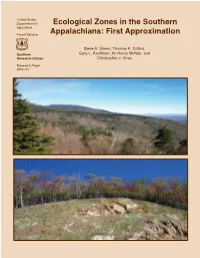

Ecological Zones in the Southern Appalachians: First Approximation

United States Department of Ecological Zones in the Southern Agriculture Forest Service Appalachians: First Approximation Steve A. Simon, Thomas K. Collins, Southern Gary L. Kauffman, W. Henry McNab, and Research Station Christopher J. Ulrey Research Paper SRS–41 The Authors Steven A. Simon, Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, NC 28802; Thomas K. Collins, Geologist, USDA Forest Service, George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, Roanoke, VA 24019; Gary L. Kauffman, Botanist, USDA Forest Service, National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, NC 28802; W. Henry McNab, Research Forester, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Asheville, NC 28806; and Christopher J. Ulrey, Vegetation Specialist, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Blue Ridge Parkway, Asheville, NC 28805. Cover Photos Ecological zones, regions of similar physical conditions and biological potential, are numerous and varied in the Southern Appalachian Mountains and are often typified by plant associations like the red spruce, Fraser fir, and northern hardwoods association found on the slopes of Mt. Mitchell (upper photo) and characteristic of high-elevation ecosystems in the region. Sites within ecological zones may be characterized by geologic formation, landform, aspect, and other physical variables that combine to form environments of varying temperature, moisture, and fertility, which are suitable to support characteristic species and forests, such as this Blue Ridge Parkway forest dominated by chestnut oak and pitch pine with an evergreen understory of mountain laurel (lower photo). DISCLAIMER The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement of any product or service by the U.S.