Feral Buffalo (Bubalus Bubalis): Distribution and Abundance in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Savanna Responses to Feral Buffalo in Kakadu National Park, Australia

Ecological Monographs, 77(3), 2007, pp. 441–463 Ó 2007 by the Ecological Society of America SAVANNA RESPONSES TO FERAL BUFFALO IN KAKADU NATIONAL PARK, AUSTRALIA 1,2,6 3,4,5 5 4,5 5 AARON M. PETTY, PATRICIA A. WERNER, CAROLINE E. R. LEHMANN, JAN E. RILEY, DANIEL S. BANFAI, 4,5 AND LOUIS P. ELLIOTT 1Department of Environmental Science and Policy, University of California, Davis, California 95616 USA 2Tropical Savannas Cooperative Research Centre, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909 Australia 3The Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia 4Faculty of Education, Health and Science. Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909, Australia 5School for Environmental Research, Charles Darwin University. Darwin, NT 0909, Australia Abstract. Savannas are the major biome of tropical regions, spanning 30% of the Earth’s land surface. Tree : grass ratios of savannas are inherently unstable and can be shifted easily by changes in fire, grazing, or climate. We synthesize the history and ecological impacts of the rapid expansion and eradication of an exotic large herbivore, the Asian water buffalo (Bubalus bubalus), on the mesic savannas of Kakadu National Park (KNP), a World Heritage Park located within the Alligator Rivers Region (ARR) of monsoonal north Australia. The study inverts the experience of the Serengeti savannas where grazing herds rapidly declined due to a rinderpest epidemic and then recovered upon disease control. Buffalo entered the ARR by the 1880s, but densities were low until the late 1950s when populations rapidly grew to carrying capacity within a decade. In the 1980s, numbers declined precipitously due to an eradication program. -

Pre-Contact Astronomy Ragbir Bhathal

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, Vol. 142, p. 15–23, 2009 ISSN 0035-9173/09/020015–9 $4.00/1 Pre-contact Astronomy ragbir bhathal Abstract: This paper examines a representative selection of the Aboriginal bark paintings featuring astronomical themes or motives that were collected in 1948 during the American- Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land in north Australia. These paintings were studied in an effort to obtain an insight into the pre-contact social-cultural astronomy of the Aboriginal people of Australia who have lived on the Australian continent for over 40 000 years. Keywords: American-Australian scientific expedition to Arnhem Land, Aboriginal astron- omy, Aboriginal art, celestial objects. INTRODUCTION tralia. One of the reasons for the Common- wealth Government supporting the expedition About 60 years ago, in 1948 an epic journey was that it was anxious to foster good relations was undertaken by members of the American- between Australia and the US following World Australian Scientific Expedition (AAS Expedi- II and the other was to establish scientific tion) to Arnhem Land in north Australia to cooperation between Australia and the US. study Aboriginal society before it disappeared under the onslaught of modern technology and The Collection the culture of an invading European civilisation. It was believed at that time that the Aborig- The expedition was organised and led by ines were a dying race and it was important Charles Mountford, a film maker and lecturer to save and record the tangible evidence of who worked for the Commonwealth Govern- their culture and society. -

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF). -

Nhulunbuy Itinerary

nd 2 OECD Meeting of Mining Regions and Cities DarwinDarwin -– Nhulunbuy Nhulunbuy 23 – 24 November 2018 Nhulunbuy Itinerary P a g e | 2 DAY ONE: Friday 23 November 2018 Morning Tour (Approx. 9am – 12pm) 1. Board Room discussions - visions for future, land tenure & other Join Gumatj CEO and other guests for an open discussion surrounding future projects and vision and land tenure. 2. Gulkula Bauxite mining operation A wholly owned subsidiary of Gumatj Corporation Ltd, the Gulkula Mine is located on the Dhupuma Plateau in North East Arnhem Land. The small- scale bauxite operation aims to deliver sustainable economic benefits to the local Yolngu people and provide on the job training to build careers in the mining industry. It is the first Indigenous owned and operated bauxite mine. 3. Gulkula Regional Training Centre & Garma Festival The Gulkula Regional training is adjacent to the mine and provides young Yolngu men and women training across a wide range of industry sectors. These include; extraction (mining), civil construction, building construction, hospitality and administration. This is also where Garma Festival is hosted partnering with Yothu Yindi Foundation. 4. Space Base The Arnhem Space Centre will be Australia’s first commercial spaceport. It will include multiple launch sites using a variety of launch vehicles to provide sub-orbital and orbital access to space for commercial, research and government organisations. 11:30 – 12pm Lunch at Gumatj Knowledge Centre 5. Gumatj Timber mill The Timber mill sources stringy bark eucalyptus trees to make strong timber roof trusses and decking. They also make beautiful furniture, homewares and cultural instruments. -

HOMELAND STORY Saving Country

ROGUE PRODUCTIONS & DONYDJI HOMELAND presents HOMELAND STORY Saving Country PRESS KIT Running Time: 86 mins ROGUE PRODUCTIONS PTY LTD - Contact David Rapsey - [email protected] Ph: +61 3 9386 2508 Mob: +61 423 487 628 Glenda Hambly - [email protected] Ph: +61 3 93867 2508 Mob: +61 457 078 513461 RONIN FILMS - Sales enquiries PO box 680, Mitchell ACT 2911, Australia Ph: 02 6248 0851 Fax: 02 6249 1640 [email protected] Rogue Productions Pty Ltd 104 Melville Rd, West Brunswick Victoria 3055 Ph: +61 3 9386 2508 Mob: +61 423 487 628 TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopses .............................................................................................. 3 Donydji Homeland History ................................................................. 4-6 About the Production ......................................................................... 7-8 Director’s Statement ............................................................................. 9 Comments: Damien Guyula, Yolngu Producer… ................................ 10 Comments: Robert McGuirk, Rotary Club. ..................................... 11-12 Comments: Dr Neville White, Anthropologist ................................. 13-14 Principal Cast ................................................................................. 15-18 Homeland Story Crew ......................................................................... 19 About the Filmmakers ..................................................................... 20-22 2 SYNOPSES ONE LINE SYNOPSIS An intimate portrait, fifty -

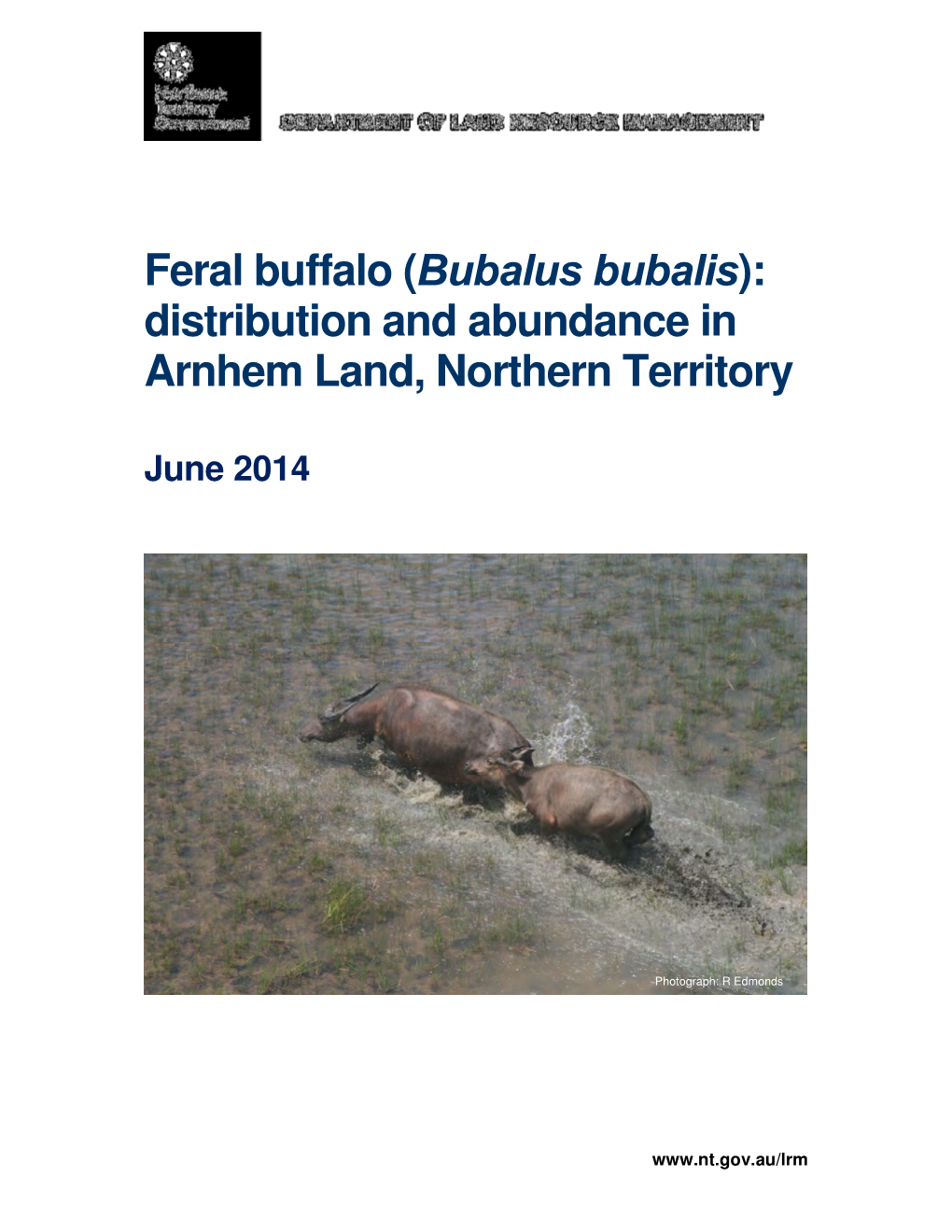

KUNINJKU PEOPLE, BUFFALO, and CONSERVATION in ARNHEM LAND: ‘IT’S a CONTRADICTION THAT FRUSTRATES US’ Jon Altman

3 KUNINJKU PEOPLE, BUFFALO, AND CONSERVATION IN ARNHEM LAND: ‘IT’S A CONTRADICTION THAT FRUSTRATES US’ Jon Altman On Tuesday 20 May 2014 I was escorting two philanthropists to rock art galleries at Dukaladjarranj on the edge of the Arnhem Land escarpment. I was there in a corporate capacity, as a direc- tor of the Karrkad-Kanjdji Trust, seeking to raise funds to assist the Djelk and Warddeken Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) in their work tackling the conservation challenges of maintain- ing the environmental and cultural values of 20,000 square kilometres of western Arnhem Land. We were flying low in a Robinson R44 helicopter over the Tomkinson River flood plains – Bulkay – wetlands renowned for their biodiversity. The experienced pilot, nicknamed ‘Batman’, flew very low, pointing out to my guests herds of wild buffalo and their highly visible criss-cross tracks etched in the landscape. He remarked over the intercom: ‘This is supposed to be an IPA but those feral buffalo are trashing this country, they should be eliminated, shot out like up at Warddeken’. His remarks were hardly helpful to me, but he had a point that I could not easily challenge mid-air; buffalo damage in an iconic wetland within an IPA looked bad. Later I tried to explain to the guests in a quieter setting that this was precisely why the Djelk Rangers needed the extra philanthropic support that the Karrkad-Kanjdji Trust was seeking to raise. * * * 3093 Unstable Relations.indd 54 5/10/2016 5:40 PM Kuninjku People, Buffalo, and Conservation in Arnhem Land This opening vignette highlights a contradiction that I want to explore from a variety of perspectives in this chapter – abundant populations of environmentally destructive wild buffalo roam widely in an Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) declared for its natural and cultural values of global significance, according to International Union for the Conservation of Nature criteria. -

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION on the TIWI ISLANDS, NORTHERN TERRITORY: Part 1. Environments and Plants

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION ON THE TIWI ISLANDS, NORTHERN TERRITORY: Part 1. Environments and plants Report prepared by John Woinarski, Kym Brennan, Ian Cowie, Raelee Kerrigan and Craig Hempel. Darwin, August 2003 Cover photo: Tall forests dominated by Darwin stringybark Eucalyptus tetrodonta, Darwin woollybutt E. miniata and Melville Island Bloodwood Corymbia nesophila are the principal landscape element across the Tiwi islands (photo: Craig Hempel). i SUMMARY The Tiwi Islands comprise two of Australia’s largest offshore islands - Bathurst (with an area of 1693 km 2) and Melville (5788 km 2) Islands. These are Aboriginal lands lying about 20 km to the north of Darwin, Northern Territory. The islands are of generally low relief with relatively simple geological patterning. They have the highest rainfall in the Northern Territory (to about 2000 mm annual average rainfall in the far north-west of Melville and north of Bathurst). The human population of about 2000 people lives mainly in the three towns of Nguiu, Milakapati and Pirlangimpi. Tall forests dominated by Eucalyptus miniata, E. tetrodonta, and Corymbia nesophila cover about 75% of the island area. These include the best developed eucalypt forests in the Northern Territory. The Tiwi Islands also include nearly 1300 rainforest patches, with floristic composition in many of these patches distinct from that of the Northern Territory mainland. Although the total extent of rainforest on the Tiwi Islands is small (around 160 km 2 ), at an NT level this makes up an unusually high proportion of the landscape and comprises between 6 and 15% of the total NT rainforest extent. The Tiwi Islands also include nearly 200 km 2 of “treeless plains”, a vegetation type largely restricted to these islands. -

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF). -

Howard Morphy Cross-Cultural Categories Yolngu Science and Local Discourses Centre for Cross-Cultural Research, the Australian National University

Howard Morphy Cross-cultural categories Yolngu science and local discourses Centre for Cross-Cultural Research, The Australian National University In Yolngu science we learn through observation. For example we observe the seasons and we see the changes in time. We watch the land and see changes in the weather patterns. In space we observe the sun and the morning star. The different stars and the moon tell us different things. Yolngu have been learning about how to read science though the moon. We've learnt to observe different cycles of the moon. It tells us when it's a good time for hunting. In different seasons different food items are ready to be eaten, like different plants. Yolngu don't just hunt for everything at once, but they go according to the different seasons. There are four seasons and Yolngu hunt according to these different seasons. Then each food source is found in abundance at the right time. We read the calendar to know for example when to go and get oysters, it also tells us when different fish is in season and when edible fruit and honey is available. Also Yolngu sing about these different seasons. They sing about the different stars. They observe and see and learn. For generations and generations people have passed on this knowledge orally. It has never been written down. It has been orally passed down to the next generation through oral history; songs, chants and stories. (Raymattja Marika, Yolngu teacher and linguist) The transformation of concepts such as science, law, or religion into cross-cultural categories has occurred in the context of discourse across cultural boundaries. -

Appropriate Terminology, Indigenous Australian Peoples

General Information Folio 5: Appropriate Terminology, Indigenous Australian Peoples Information adapted from ‘Using the right words: appropriate as ‘peoples’, ‘nations’ or ‘language groups’. The nations of terminology for Indigenous Australian studies’ 1996 in Teaching Indigenous Australia were, and are, as separate as the nations the Teachers: Indigenous Australian Studies for Primary Pre-Service of Europe or Africa. Teacher Education. School of Teacher Education, University of New South Wales. The Aboriginal English words ‘blackfella’ and ‘whitefella’ are used by Indigenous Australian people all over the country — All staff and students of the University rely heavily on language some communities also use ‘yellafella’ and ‘coloured’. Although to exchange information and to communicate ideas. However, less appropriate, people should respect the acceptance and use language is also a vehicle for the expression of discrimination of these terms, and consult the local Indigenous community or and prejudice as our cultural values and attitudes are reflected Yunggorendi for further advice. in the structures and meanings of the language we use. This means that language cannot be regarded as a neutral or unproblematic medium, and can cause or reflect discrimination due to its intricate links with society and culture. This guide clarifies appropriate language use for the history, society, naming, culture and classifications of Indigenous Australian and Torres Strait Islander people/s. Indigenous Australian peoples are people of Aboriginal and Torres -

Final Report

final report knowledge for managing Australian landscapes Kantri is for Laif (Country is for Life) A Strategy for the Promotion of Indigenous Knowledge and the Development of Indigenous Livelihoods on the Remote north Australian Indigenous Estate. A Land & Water Australia, CRC-TSM and NAILSMA Project Initiative Published by Land & Water Australia Product Code PN30198 Postal address GPO Box 2182, Canberra ACT 2601 Office location Level 1, The Phoenix 86 Northbourne Avenue, Braddon ACT 2612 Telephone 02 6263 6000 Email [email protected] Internet www.lwa.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia, July 2009 Disclaimer The information contained in this publication is intended for general use, to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the sustainable management of land, water and vegetation. It includes general statements based on scientific research. Readers are advised and need to be aware that this information may be incomplete or unsuitable for use in specific situations. Before taking any action or decision based on the information in this publication, readers should seek expert professional, scientific and technical advice and form their own view of the applicability and correctness of the information. To the extent permitted by law, the Commonwealth of Australia, Land & Water Australia (including its employees and consultants), and the authors of this publication do not assume liability of any kind whatsoever resulting from any person’s use or reliance upon the content of this publication. Kantri is for Laif (Country is for Life) Na‐ja narnu‐yuwa narnu‐walkurra barra, wirrimalaru, barni‐wardimantha, Barni‐ngalngandaya, nakari wabarrangu li‐wankala, li‐ngambalanga kuku, li‐ngambalanga murimuri, li‐ngambalanga ngabuji, li‐ngambalanga kardirdi kalu‐kanthaninya na‐ja narnu‐yuwa, jiwini awarala, anthaa yurrngumantha barra. -

The Land and Its People

CHAPTER 2 THE LAND AND ITS PEOPLE The environment of Northern Australia can seem Earlier settlers in southern Australia may have 1 Boys fishing, Elin Beach, an odd mix. While it has an intimate familiarity found the native vegetation there strange too Hopevale, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by to local Indigenous people, to those accustomed but were able to transform it to a more homely Kerry Trapnell to temperate Australia, it has a strange character. fashion, with European plants and animals. That Fires seem too pervasive and frequent; many has not been the case in the North; for most of the native trees are at least semi-deciduous Australians, it remains a foreign and unfamiliar (they lose their leaves to save water during the landscape, and even its society seems different. Dry season); there is too much grass, some of it taller than a person; the eucalypts don’t have In this chapter we provide an overview of the that familiar evocative reassuring smell; even North’s geography and consider how it differs the colours of the bush seem somewhat harder. from the rest of Australia. We also introduce Parts of the landscape seem decidedly African its regions, weather, landscape features and in flavour, with the boab trees but without the people. Finally, we discuss the North’s current lions. Indeed, the link across the Indian Ocean land tenure and economies, as well as the way is explicitly marked: the Kimberley region is in which the land is managed. These facts and named for its resemblance to the landscape figures provide the background necessary to in southern Africa of the same name.