The Land and Its People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Contact Astronomy Ragbir Bhathal

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, Vol. 142, p. 15–23, 2009 ISSN 0035-9173/09/020015–9 $4.00/1 Pre-contact Astronomy ragbir bhathal Abstract: This paper examines a representative selection of the Aboriginal bark paintings featuring astronomical themes or motives that were collected in 1948 during the American- Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land in north Australia. These paintings were studied in an effort to obtain an insight into the pre-contact social-cultural astronomy of the Aboriginal people of Australia who have lived on the Australian continent for over 40 000 years. Keywords: American-Australian scientific expedition to Arnhem Land, Aboriginal astron- omy, Aboriginal art, celestial objects. INTRODUCTION tralia. One of the reasons for the Common- wealth Government supporting the expedition About 60 years ago, in 1948 an epic journey was that it was anxious to foster good relations was undertaken by members of the American- between Australia and the US following World Australian Scientific Expedition (AAS Expedi- II and the other was to establish scientific tion) to Arnhem Land in north Australia to cooperation between Australia and the US. study Aboriginal society before it disappeared under the onslaught of modern technology and The Collection the culture of an invading European civilisation. It was believed at that time that the Aborig- The expedition was organised and led by ines were a dying race and it was important Charles Mountford, a film maker and lecturer to save and record the tangible evidence of who worked for the Commonwealth Govern- their culture and society. -

Nhulunbuy Itinerary

nd 2 OECD Meeting of Mining Regions and Cities DarwinDarwin -– Nhulunbuy Nhulunbuy 23 – 24 November 2018 Nhulunbuy Itinerary P a g e | 2 DAY ONE: Friday 23 November 2018 Morning Tour (Approx. 9am – 12pm) 1. Board Room discussions - visions for future, land tenure & other Join Gumatj CEO and other guests for an open discussion surrounding future projects and vision and land tenure. 2. Gulkula Bauxite mining operation A wholly owned subsidiary of Gumatj Corporation Ltd, the Gulkula Mine is located on the Dhupuma Plateau in North East Arnhem Land. The small- scale bauxite operation aims to deliver sustainable economic benefits to the local Yolngu people and provide on the job training to build careers in the mining industry. It is the first Indigenous owned and operated bauxite mine. 3. Gulkula Regional Training Centre & Garma Festival The Gulkula Regional training is adjacent to the mine and provides young Yolngu men and women training across a wide range of industry sectors. These include; extraction (mining), civil construction, building construction, hospitality and administration. This is also where Garma Festival is hosted partnering with Yothu Yindi Foundation. 4. Space Base The Arnhem Space Centre will be Australia’s first commercial spaceport. It will include multiple launch sites using a variety of launch vehicles to provide sub-orbital and orbital access to space for commercial, research and government organisations. 11:30 – 12pm Lunch at Gumatj Knowledge Centre 5. Gumatj Timber mill The Timber mill sources stringy bark eucalyptus trees to make strong timber roof trusses and decking. They also make beautiful furniture, homewares and cultural instruments. -

KUNINJKU PEOPLE, BUFFALO, and CONSERVATION in ARNHEM LAND: ‘IT’S a CONTRADICTION THAT FRUSTRATES US’ Jon Altman

3 KUNINJKU PEOPLE, BUFFALO, AND CONSERVATION IN ARNHEM LAND: ‘IT’S A CONTRADICTION THAT FRUSTRATES US’ Jon Altman On Tuesday 20 May 2014 I was escorting two philanthropists to rock art galleries at Dukaladjarranj on the edge of the Arnhem Land escarpment. I was there in a corporate capacity, as a direc- tor of the Karrkad-Kanjdji Trust, seeking to raise funds to assist the Djelk and Warddeken Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) in their work tackling the conservation challenges of maintain- ing the environmental and cultural values of 20,000 square kilometres of western Arnhem Land. We were flying low in a Robinson R44 helicopter over the Tomkinson River flood plains – Bulkay – wetlands renowned for their biodiversity. The experienced pilot, nicknamed ‘Batman’, flew very low, pointing out to my guests herds of wild buffalo and their highly visible criss-cross tracks etched in the landscape. He remarked over the intercom: ‘This is supposed to be an IPA but those feral buffalo are trashing this country, they should be eliminated, shot out like up at Warddeken’. His remarks were hardly helpful to me, but he had a point that I could not easily challenge mid-air; buffalo damage in an iconic wetland within an IPA looked bad. Later I tried to explain to the guests in a quieter setting that this was precisely why the Djelk Rangers needed the extra philanthropic support that the Karrkad-Kanjdji Trust was seeking to raise. * * * 3093 Unstable Relations.indd 54 5/10/2016 5:40 PM Kuninjku People, Buffalo, and Conservation in Arnhem Land This opening vignette highlights a contradiction that I want to explore from a variety of perspectives in this chapter – abundant populations of environmentally destructive wild buffalo roam widely in an Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) declared for its natural and cultural values of global significance, according to International Union for the Conservation of Nature criteria. -

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF). -

Queensland Environmental Offsets Policy Version 1.10

Queensland Environmental Offsets Policy Page 1 of 68 • EPP/2021/1658 • Version 1.10 • Last Reviewed: 03/03/2021 Department of Environment and Science Page 1 of 68 • EPP/2021/1658 • Version 1.10 • Last Reviewed: 03/03/2021 Department of Environment and Science Prepared by: Conservation Policy and Planning, Department of Environment and Science © State of Queensland, 2021. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer While this document has been prepared with care it contains general information and does not profess to offer legal, professional or commercial advice. The Queensland Government accepts no liability for any external decisions or actions taken on the basis of this document. Persons external to the Department of Environment and Science should satisfy themselves independently and by consulting their own professional advisors before embarking on any proposed course of action. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5470. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. -

Land Zones of Queensland

P.R. Wilson and P.M. Taylor§, Queensland Herbarium, Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts. © The State of Queensland (Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts) 2012. Copyright inquiries should be addressed to <[email protected]> or the Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts, 111 George Street, Brisbane QLD 4000. Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3224 8412. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3224 8412 or email <[email protected]>. ISBN: 978-1-920928-21-6 Citation This work may be cited as: Wilson, P.R. and Taylor, P.M. (2012) Land Zones of Queensland. Queensland Herbarium, Queensland Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts, Brisbane. 79 pp. Front Cover: Design by Will Smith Images – clockwise from top left: ancient sandstone formation in the Lawn Hill area of the North West Highlands bioregion – land zone 10 (D. -

Appropriate Terminology, Indigenous Australian Peoples

General Information Folio 5: Appropriate Terminology, Indigenous Australian Peoples Information adapted from ‘Using the right words: appropriate as ‘peoples’, ‘nations’ or ‘language groups’. The nations of terminology for Indigenous Australian studies’ 1996 in Teaching Indigenous Australia were, and are, as separate as the nations the Teachers: Indigenous Australian Studies for Primary Pre-Service of Europe or Africa. Teacher Education. School of Teacher Education, University of New South Wales. The Aboriginal English words ‘blackfella’ and ‘whitefella’ are used by Indigenous Australian people all over the country — All staff and students of the University rely heavily on language some communities also use ‘yellafella’ and ‘coloured’. Although to exchange information and to communicate ideas. However, less appropriate, people should respect the acceptance and use language is also a vehicle for the expression of discrimination of these terms, and consult the local Indigenous community or and prejudice as our cultural values and attitudes are reflected Yunggorendi for further advice. in the structures and meanings of the language we use. This means that language cannot be regarded as a neutral or unproblematic medium, and can cause or reflect discrimination due to its intricate links with society and culture. This guide clarifies appropriate language use for the history, society, naming, culture and classifications of Indigenous Australian and Torres Strait Islander people/s. Indigenous Australian peoples are people of Aboriginal and Torres -

Koala Context

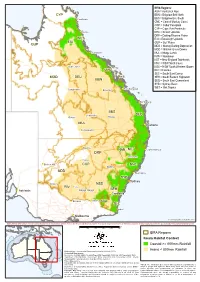

IBRA Regions: AUA = Australian Alps CYP BBN = Brigalow Belt North )" Cooktown BBS = Brigalow Belt South CMC = Central Mackay Coast COP = Cobar Peneplain CYP = Cape York Peninsula ") Cairns DEU = Desert Uplands DRP = Darling Riverine Plains WET EIU = Einasleigh Uplands EIU GUP = Gulf Plains GUP MDD = Murray Darling Depression MGD = Mitchell Grass Downs ") Townsville MUL = Mulga Lands NAN = Nandewar NET = New England Tablelands NNC = NSW North Coast )" Hughenden NSS = NSW South Western Slopes ") CMC RIV = Riverina SEC = South East Corner MGD DEU SEH = South Eastern Highlands BBN SEQ = South East Queensland SYB = Sydney Basin ") WET = Wet Tropics )" Rockhampton Longreach ") Emerald ") Bundaberg BBS )" Charleville )" SEQ )" Quilpie Roma MUL ") Brisbane )" Cunnamulla )" Bourke NAN NET ") Coffs Harbour DRP ") Tamworth )" Cobar ") Broken Hill COP NNC ") Dubbo MDD ") Newcastle SYB ") Sydney ") Mildura NSS RIV )" Hay ") Wagga Wagga SEH Adelaide ") ") Canberra ") ") Echuca Albury AUA SEC )" Eden ") Melbourne © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 INDICATIVE MAP ONLY: For the latest departmental information, please refer to the Protected Matters Search Tool and the Species Profiles & Threats Database at http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/index.html km 0 100 200 300 400 500 IBRA Regions Koala Habitat Context Coastal >= 800mm Rainfall Produced by: Environmental Resources Information Network (2014) Inland < 800mm Rainfall Contextual data source: Geoscience Australia (2006), Geodata Topo 250K Topographic Data and 10M Topographic Data. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2012). Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA), Version 7. Other data sources: Commonwealth of Australia, Bureau of Meteorology (2003). Mean annual rainfall (30-year period 1961-1990). Caveat: The information presented in this map has been provided by a Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2013). -

9 Presidential Address the Discovery Of

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Queensland eSpace 9 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS THE DISCOVERY OF AUSTRALIA [By SIR RAPHAEL CILENTO.] (Read on September 25, 1958.) Accidental Factors As far back almost as recorded history goes there had been speculation about the existence of a great "Southland" extending to the South Pole to balance the great land mass of the North. Ancient Chinese geo graphers are said to mention recognisable places in Western New Guinea; the Japanese claim their sailors knew New Guinea, Cape York Peninsula, and the Gulf of Carpentaria many centuries ago; the Malays from Indonesia certainly visited our northern coasts, for cen turies as they do still. From the beginning of the 14th century, however, while the Moslem power declined in the West (in Spain and North Africa) it revived to a new pitch of fanatical fervour in the Middle East, with the incoming of the Turks. They straddled Asia Minor and Mesopotamia and cut the caravan routes by which Europe was sup plied with spices. The best intelligences of Western Europe began to search ancient geographical treatises for a new route to the "Spice Islands," which are the East Indies — Indonesia—lying above the shores of Queensland. This search for the "Spice Islands" was eventually to result in the charting of all Africa southerly; the discovery of the West Indies and of North, South and Central America westerly; of the Pacific Ocean and its islands behind the unsuspected land mass of America, and, last of all, of Queensland—^the first found finger of Aus tralia. -

KAKADU–ARNHEM LAND REGION, NORTHERN TERRITORY J. Nott

KAKADU–ARNHEM LAND REGION, NORTHERN TERRITORY J. Nott School of Tropical Environment Studies and Geography, James Cook University, PO Box 6811, Cairns, QLD 4870 [email protected] INTRODUCTION Alleged variations in the characteristics of weathering profiles have played a significant role in interpreting the evolution of Darwin Region landscape in the north of the Northern Territory. The region, ARNHEM Walker River which experiences a monsoonal tropical wet–dry climate, is part LAND Groote of the North Australian Craton (Figure 1) and has a landscape Kakadu N.P. Eylandt that is much older than previously assumed. This greater age Gulf of Parsons Range Carpentaria of landscape is indicated by a change from marine Cretaceous Tawallah and sediments on the lowland plain to terrestrial Cretaceous sediments Yiyinti Ranges on the upland plateau, and also by the in situ (as opposed to NORTHERN TERRITOR Y ‘detrital’) nature of deep weathering profiles across the lowland plains. A brief account of the changing views on the age and Kimberley evolution of the landscape in the north of the Northern Territory Region is presented below. NT QLD WA PHYSICAL SETTING SA The landscape of the north of the Northern Territory (Figure 1) NSW is dominated by plains of low relief and generally flat topped VIC Australian Craton uplands eroded from Proterozoic sandstones. The plains, by TAS North Australian Craton contrast, are generally underlain by Proterozoic metasediments and granites. Cretaceous marine sediments, associated with the 400 km Neocomian to Albian marine transgression(s), rest unconformably RRAfKAL01-03 upon the Proterozoic strata in the plains region. -

Yolngu Life in the Northern Territory of Australia: the Significance of Community and Social Capital

On-Line Papers Copyright This online paper may be cited or briefly quoted in line with the usual academic conventions. You may also download them for your own personal use. This paper must not be published elsewhere (e.g. to mailing lists, bulletin boards etc.) without the author’s explicit permission. Please note that if you copy this paper you must: • include this copyright note • not use the paper for commercial purposes or gain in any way • you should observe the conventions of academic citation in a version of the following form: www.cdu.edu.au/centres/inc/pdf/Yolngulife.pdf Publication Details: This web page was last revised on 12/12/2006 Yolngu Life in the Northern Territory of Australia: The Significance of Community and Social Capital Michael Christie and John Greatorex. School Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Aus- tralia http://www.cdu.edu.au/centres/inc [email protected] [email protected] Yolngu Life in the Northern Territory of Australia: The Significance of Community and Social Capital Michael Christie and John Greatorex The notion of social capital has had wide currency in mainstream social policy debate in recent years, with commonly used definitions emphasising three factors: norms, networks and trust. Yolngu Aboriginal people have their own perspectives on norms, networks and trust relationships. This article uses concepts from Yolngu philosophy to explore these perspectives in three contexts: at the former mission settlements, at homeland centres, and among "long-grassers" in Darwin. The persistence of the components of social capital at different levels in particular contexts should be seen by government policy makers as an opportunity to engage in a social development dialogue with Yolngu, aimed at identifying the specific contexts in which Yolngu social capital can be maximised. -

Dutch Exploration of Australia

EBOOK REAU5058_sample SAMPLE Contents Teachers’ Notes 4 Section 3: Early Exploration Curriculum Links 5 of the Land 42 List of Acknowledgements 6 Exploring the Australian Land 43 More Explorations of the Australian Land 44 Early Explorers of the Land 45 Section 1: Maritime Explorers Crossing the Blue Mountains 46 of Australia and Indigenous John Oxley 47 7 Australians Discovering Gold 48 Early Dutch Maritime Explorers of Australia 8 Life on the Goldfields 49 Early British Maritime Explorers of Australia 9 Goldfields Language 50 The Dutch 10 The Gold Rush 51 Putting Things in Order 11 The Eureka Flag 52 Timeline of Early Maritime Explorers 12 William Dampier 13 Captain James Cook 14 Section 4: Australian Gathering Evidence on the Endeavour 15 Bushrangers 53 Maritime Explorers Meet the First Australians 16 Bushrangers 54 Aboriginal Musical Instruments 17 Bushranging 55 The First Australians 1 18 The Wild Colonial Boy 56 The First Australians 2 19 Infamous Bushrangers 57 Aboriginal Hunting and Gathering Tools 20 Gardiner and Power 58 Aboriginal Music 21 Ben Hall 59 Aboriginal Art 22 Ben Hall 60 Ideas in Aboriginal Art 23 Ned Kelly 61 Careful Use of the Natural Environment 24 Ned Kelly 62 Explorers and the First Australians 25 Celebrating Aboriginality 26 SAMPLEAnswers 63-68 Section 2: European Colonisation 27 The First Fleet 28 European Colonies and Expansion 29 The Three Fleets 30 The Journey 31 Captain Arthur Phillip 32 Early Problems 33 New Colonies 34 Convict Life 35 Convict Folk Songs 1 36 Convict Folk Songs 2 37 Convict Love 38 Port Arthur Convict Colony 39 Impact of Colonisation on Aborigines 40 Negative Impact on Aborigines 41 3 History of Australia Early Dutch Maritime Explorers of Australia In the 1600s many ships were sent from Holland to look for a faster way to reach the East Indies (Indonesia) because at this time Holland traded goods with the people there.