Wicksteed and the Jevonian Revolution in the Second Generation1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The End of Economics, Or, Is

THE END OF ECONOMICS, OR, IS UTILITARIANISM FINISHED? By John D. Mueller James Madison Program Fellow Fellow of The Lehrman Institute President, LBMC LLC Princeton University, 127 Corwin Hall, 15 April 2002 Summary. According to Lionel Robbins’ classic definition, “Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means that have alternate uses.” Yet most modern economists assume that economic choice involves only the means and not to the ends of human action. The reason seems to be that most modern economists are ignorant of the history of their own discipline before Adam Smith or Jeremy Bentham. Leading economists like Gary Becker attempt to explain all human behavior, including love and hate, as a maximization of “utility.” But historically and logically, an adequate description of economic choice has always required both a ranking of persons as ends and a ranking of scarce goods as means. What is missing from modern economics is an adequate description of the ranking of persons as ends. This is reflected in the absence of a satisfactory microeconomic explanation (for example, within the household) as to how goods are distributed to their final users, and in an overemphasis at the political level on an “individualistic social welfare function,” by which policymakers are purported to add up the preferences of a society of selfish individuals and determine all distribution from the government downwards, as if the nation or the world were one large household. As this “hole” in economic theory is recognized, an army of “neo-scholastic” economists will find full employment for the first few decades of the 21st Century, busily rewriting the Utilitarian “economic approach to human behavior” that dominated the last three decades of the 20th Century. -

Marginal Revolution

MARGINAL REVOLUTION It took place in the later half of the 19th century Stanley Jevons in England, Carl Menger in Austria and Leon walras at Lausanne, are generally regarded as the founders of marginalist school Hermann Heinrich Gossen of Germany is considered to be the anticipator of the marginalist school The term ‘Marginal Revolution’ is applied to the writings of the above economists because they made fundamental changes in the apparatus of economic analysis They started looking at some of the important economic problems from an altogether new angle different from that of classical economists Marginal economists has been used to analyse the single firm and its behavior, the market for a single product and the formation of individual prices Marginalism dominated Western economic thought for nearly a century until it was challenged by Keynesian attack in 1936 (keynesian economics shifted the sphere of enquiry from micro economics to macro economics where the problems of the economy as a whole are analysed) The provocation for the emergence of marginalist school was provided by the interpretation of classical doctrines especially the labour theory of value and ricardian theory of rent by the socialists Socialists made use of classical theories to say things which were not the intention of the creators of those theories So the leading early marginalists felt the need for thoroughly revising the classical doctrines especially the theory of value They thought by rejecting the labour theory of value and by advocating the marginal utility theory of value, they could strike at the theoretical basis of socialism Economic Ideas of Marginalist School This school concentrated on the ‘margin’ to explain economic phenomena. -

Energy As a Factor of Production: Historical Roots in the American Institutionalist Context Antoine Missemer, Franck Nadaud

Energy as a Factor of Production: Historical Roots in the American Institutionalist Context Antoine Missemer, Franck Nadaud To cite this version: Antoine Missemer, Franck Nadaud. Energy as a Factor of Production: Historical Roots in the American Institutionalist Context. Energy Economics, Elsevier, 2020, 86, pp.104706. 10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104706. halshs-02467734 HAL Id: halshs-02467734 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02467734 Submitted on 26 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. - Authors’s post-print - - published in Energy Economics (2020), 86, 104706 - ENERGY AS A FACTOR OF PRODUCTION: HISTORICAL ROOTS IN THE AMERICAN INSTITUTIONALIST CONTEXT - * Antoine MISSEMER † Franck NADAUD - Full reference: MISSEMER, Antoine and NADAUD, Franck. 2020. “Energy as a Factor of Production: Historical Roots in the American Institutionalist Context”. Energy Economics, 86, 104706. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104706] The pagination of the published version is indicated in the margin. - Abstract The relationship between energy and economic output is today discussed through the decoupling issue. A pioneering historical attempt to measure this relationship can be found in contributions by F. G. Tryon et al. at the Brookings Institution in the 1920s-1930s, in the American institutionalist context. -

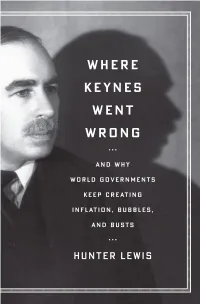

Where Keynes Went Wrong

Praise for Where Keynes Went Wrong “[An] impassioned . and . much needed book. In plain prose, . Hunter Lewis . begins by patiently walking us through precisely what Keynes said . then reveals why Keynes’s work is ‘remarkably unsupported by evidence or logic.’ Lewis does much more besides, showing how Keynesianism has lived in the minds and hearts of politicians, with disastrous results.” —Gene Epstein, Barron’s “Lewis has exposed with unmatched clarity the lineaments of Keynes’s system and enabled us to see exactly its disabling defects. Keynes defied common sense, unable to sustain the brilliant para- doxes that his fertile intellect constantly devised. Lewis’s book is an ideal guide to Keynes’s dangerous and destructive economics. .” —David Gordon, LewRockwell.com “Just what the world needs, and just in time. Keynes is demolished and his quack system refuted. But this wonderful book does more. It restores clear thinking and common sense to their rightful places in the economic policy debate. Three cheers for Hunter Lewis!” —James Grant, Editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer “Hunter Lewis has written a splendid book called Where Keynes We nt Wrong. The dissection of the English economist who died in 1946 is especially timely, given that the past two administra- tions and the current one are identical in believing wholeheart- edly in . key Keynesian dogma.” —Patrick McIlheran, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel “[This] compelling, powerful, and extremely readable book . is fantastic. ‘Must’ reading.” —Kevin Price, CBS and CNN Radio and BizPlusBlog “Lewis has done a service, even if in the negative, of concisely and critically summarizing Keynes’s economic theories, and his book will make readers think.” —Library Journal “[This] highly readable . -

Journal of Energy History Revue D'histoire De L'énergie Les Économistes Et La Fin Des Énergies Fossiles (Antoine Missemer

Journal of Energy History Revue d’histoire de l’énergie AUTHOR Antonin Pottier Les économistes et la fin des Centre International de énergies fossiles (Antoine Recherche sur l’Environnement et le Missemer, 2017) Développement (CIRED), École des Hautes Études en Bibliographic reference Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Antoine Missemer, Les économistes et la fin des énergies fos- France siles (1865-1931) (Paris : Garnier, 2017). POST DATE Abstract 06/02/2020 In Les économistes et la fin des énergies fossiles, ISSUE NUMBER Antoine Missemer explores the different ways by which JEHRHE #2 economists have made fossil fuels an object of eco- SECTION nomic analysis, in the period that runs from The Coal Reviews Question by William Stanley Jevons to Harold Hotelling’s KEYWORDS 1931 paper. He is interested in the fear of resource Coal, Oil, Industry, exhaustion and its impact on industrial development, Knowledge, Public policy but also reports on the theories that pay attention to DOI the economic activities of fossil fuels producers. in progress Plan of the article TO CITE THIS ARTICLE → The Coal Question as an autonomising work Antonin Pottier, “Les → Discussion of the autonomisation thesis économistes et la fin des → American conservationism énergies fossiles (Antoine → Nature as an asset Missemer, 2017)”, Journal of → A retrospective object? Energy History/Revue d’Histoire de l’Énergie [Online], n°2, published 06 february 2020, consulted XXX, URL: http:// energyhistory.eu/node/123 ISSN 2649-3055 JEHRHE #2 | REVIEWS P. 2 POTTIER | LES ÉCONOMISTES ET LA FIN DES ÉNERGIES FOSSILES (ANTOINE MISSEMER, 2017) analysis? Antoine Missemer seeks to engage with these questions in his research. -

Economics, Psychology, and the History of Demand Theory

Economics, Psychology, and the History of Consumer Choice Theory Paper for Conference on The History of Recent Economics (HISRECO) University of Paris X June 22-24, 2007 D. Wade Hands Department of Economics University of Puget Sound Tacoma, WA 98416 USA [email protected] May 2007 Version 2.0 13,693 Words Draft for discussion purposes only. Please do not quote. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the European Association for Evolutionary Political Economy Conference in Istanbul, Turkey, in November 2006 and at the Whittemore School of Business and Economics, University of New Hampshire, in February 2007. I would like to thank John Davis, Harro Maas, and a number of people in the audience at Istanbul and UNH for helpful comments. 0. Introduction The relationship between psychology and consumer choice theory has been long and tumultuous: a veritable seesaw of estrangement and warm reconciliation. Starting with the British neoclassicism of Jevons and Edgeworth, and moving to contemporary economic theory, it appears that psychology was quite in, then clearly out, and now (possibly) coming back in. If one moves farther back in time and takes the view that the classical tradition was grounded in a natural – and thus non-social, non-mental, and non– psychological – order (Schabas 2005), then the scorecard becomes out, in, out, and (possibly) back in. A tumultuous relationship indeed. The purpose of this paper is to provide a critical examination of this turbulent relationship. The argument is presented in three parts. The first section provides a summary of the standard story about the relationship between psychology and consumer choice theory from the early neoclassicals to the present time. -

The Economics of W.S.Jevons

THE ECONOMICS OF W.S.JEVONS Sandra Peart London and New York First published 1996 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 © 1996 Sandra Peart All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by an electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Peart, Sandra. The economics of W.S.Jevons/Sandra Peart. p. cm.—(Routledge studies in the history of economics; 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Jevons, William Stanley, 1835–1882. 2. Economists—Great Britain—Biography. 3. Economics—Great Britain—History—19th century. I. Title. II. Series. HB103.J5P4 1996 95–51459 330.157–dc20 CIP ISBN 0-203-02249-1 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-20445-X (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-06713-8 Truth is the iron hand within the velvety glove, and the one who has truth & good logic on his side will ultimately overcome millions who are led by confused and contradictory ideas. -

The Psychologicaltendency in Recent Political Economy (1892)

document 14 The Psychological Tendency in Recent Political Economy (1892) Conrad Schmidt* Source: Conrad Schmidt, ‘Die psychologische Richtung in der neueren Natio- nal-Oekonomie’, Die Neue Zeit, 10. 1891–2, 2. Bd. (1892), h. 41, s. 421–9, 459–64. Introduction by the Editors There is much irony in the fact that just as Marx was working to complete Capital, and then Engels to make Volumes ii and iii of Capital available, a new approach to economic theory, beginning from a viewpoint exactly the opposite of Marx’s, was emerging in Britain and continental Europe. The so- called ‘marginalist revolution’, a response to the disintegration of the Ricardian * Conrad Schmidt (1863–1932) was a German economist and journalist. In the mid-1880s he studied in Berlin and received his doctorate in 1887 in Leipzig with the thesis Der natürliche Arbeitslohn (The Natural Wage), in which he compared the wages and exploitation theories of Johann Karl Rodbertus and Karl Marx. Schmidt rejected Marx’s theory as an unproven hypothesis in favour of Rodbertus’s views, which were based on the assumption of natural rights. After further study, Schmidt revised this judgement and became a follower of Marxism. In 1889 he published a book for the so-called ‘prize-essay competition’, in which Engels challenged the economists to explain how the formation of an average rate of profit could be made compatible with law of labour value – a solution finally revealed with the publication of the third volume of Capital in 1894. Schmidt’s book was called The Average Rate of Profit on the Basis of Marx’s Law of Value (Schmidt 1889), and gave rise to a lively correspondence between him and Engels. -

One the Prying Eyes of the Natural Scientist

Cambridge University Press 0521827124 - William Stanley Jevons and the Making of Modern Economics Harro Maas Excerpt More information one The Prying Eyes of the Natural Scientist William Stanley Jevons (1835–1882) isunquestionably one of thegreat minds inthe history of economics. Today, he is remembered as one of the “fathers” of the so-called marginalist revolution in economics. Withhis Theory of Po- litical Economy (1871), decisions of economic agents came to be analysedby means of thecalculus, interms ofdeliberations over marginalincrements of utility. In this “mechanics of utility and self-interest” (TPE2 90), economic agents – whetherintheir roleof consumers, workmen, or other – came to be seen as maximising utilityfunctions. Themarginalist revolution was a definitive breakwith the labour theory of value–value came to be iden- tifiedwith exchange value, and this was identifiedwith marginal utilities, not with the costs ofproduction. Jevons isalso rememberedforhis inno- vative contributions to theempirical, statistical study of the economy. He ardently propagated the use of graphstopictureand analyse statisticaldata. He introducedindex numberstomake causalinferences about economic phenomena. In short, there isnoparticleof economicscience, theoretical or empirical,towhich Jevons did not make important contributions that are, today,consideredrevolutionary. Jevons is one of the fathersof modern economics, indeed. This summary evaluation of the importance of Jevons’s contributions to economics contrasts starkly with the image wegain fromasuperficial -

Hayek, Institutions, and Coordination: Essays in the History of Economic Thought and Methodology

1 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE ECONOMIA, ADMINISTRAÇÃO, CONTABILIDADE E GESTÃO DE POLÍTICAS PÚBLICAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ECONOMIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ECONOMIA Hayek, Institutions, and Coordination: Essays in the History of Economic Thought and Methodology Keanu Telles da Costa Brasília 2020 2 Keanu Telles da Costa Hayek, Institutions, and Coordination: Essays in the History of Economic Thought and Methodology Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Economia, da Faculdade de Economia, Administração, Contabilidade e Gestão Pública, da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Economia. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Mauro Boianovsky Universidade de Brasília Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade Departamento de Economia Brasília 2020 3 Keanu Telles da Costa Hayek, Institutions, and Coordination: Essays in the History of Economic Thought and Methodology Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Economia, da Faculdade de Economia, Administração, Contabilidade e Gestão Pública, da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para à obtenção do título de Mestre em Economia. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Mauro Boianovsky Departamento de Economia, Universidade de Brasília Prof. Dr. Rodrigo Peñaloza Departamento de Economia, Universidade de Brasília Prof. Dr. Fabio Barbieri Departamento de Economia, Universidade de São Paulo – Ribeirão Preto Brasília 2020 4 5 Agradecimentos O motivo principal de minha preferência, e ao final de minha escolha, pelo programa de pós-graduação em Economia da Universidade de Brasília (UnB) se resume na oportunidade de poder partilhar, absorver e trabalhar com a principal referência latino- americana e uma das referências mundiais na área de história do pensamento econômico e metodologia, áreas de meu intenso e juvenil interesse desde os meus anos iniciais de formação. -

Working Paper No. 36, the Rise of Marginalism: the Philosophical Foundations of Neoclassical Economic Thought

Portland State University PDXScholar Working Papers in Economics Economics 5-19-2014 Working Paper No. 36, The Rise of Marginalism: The Philosophical Foundations of Neoclassical Economic Thought Emily Pitkin Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/econ_workingpapers Part of the Economic History Commons, and the Economic Theory Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Pitkin, Emily. "The Rise of Marginalism: The Philosophical Foundations of Neoclassical Economic Thought, Working Paper No. 36", Portland State University Economics Working Papers. 36. (19 May 2014) i + 14 pages. This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Working Papers in Economics by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Rise of Marginalism: The Philosophical Foundations of Neoclassical Economic Thought Working Paper No. 36 Authored by: Emily Pitkin A Contribution to the Working Papers of the Department of Economics, Portland State University Submitted for: EC 460, “History of Economic Thought” 19 May 2014; i + 14 pages Prepared for Professor John Hall Abstract: This inquiry examines the works of the early thinkers in marginalist theory and seeks to establish that certain philosophical assumptions about the nature of man led to the development and ultimate ascendance of neoclassical thought in the field of economics. Jeremy Bentham’s key assumption, which he develops in his 1781 work, A Fragment on Government and an Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, that men are driven by the forces of pain and pleasure led directly to William Stanley Jevons and Carl Menger’s investigation and advancement of utility maximization theory one hundred years after Bentham, in 1871. -

Theories of Economic System

Theories of Global Economic System 1 • Mercantilism deals with the economic policy of the time between the Middle Ages and the age of laissez faire or as some scholars put it, 16th to 18th century (Viner, 1968; Kuhn 1963). • The period under which mercantilism held sway was not uniform in Europe. • It began and ended at quite different dates in the various countries and regions of Europe (Heckscher, 1955). • Mercantilism promoted governmental regulations of a nation’s economy for the purpose of augmenting state power at the expense of rival national powers. • It was the economic counterpart of political absolutism. • The 17th century publicists, most notably - Thomas Mun in England, Jean-Baptiste Colbert in France, and Antonio Serra in Italy – never, however, used the term themselves; it was given currency by the Scottish economist, Adam Smith in his Wealth of Nations(1776) 2 • Eli Heckscher (1955) identified the environment out of which mercantilism evolved as: – The ruin or disintegration of the universal Roman Empire – the rise and consolidation of states, limited in territory and influence though sovereign within their own borders, which grew up on the ruins of the universal Roman Empire. – Henceforth, the state stood at the centre of mercantilist endeavours as they developed historically: the state was both the subject and object of mercantilist economic policy. – The state had to assert itself in two opposing directions. On the one hand, the demands of the social institutions of the confined territories had to be defended against the universalism characteristic of the Middle Ages. On the other hand , the state had to assert its economic independence.