South Worcestershire Development Plan 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mondays to Fridays Saturdays Sundays

540 Evesham - Beckford - Bredon - Tewkesbury Astons of Kempsey Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions 1 1 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 1 2 2 1 1 3 3 Greenhill, adj Prince Henry's High School 1545 1540 Evesham, Bus Station (Stand B) 0734 0737 0748 0848 0948 1048 1148 1248 1348 1448 1448 1548 1550 1548 1648 1748 Bengeworth, opp Cemetery 0742 Four Pools, adj Woodlands 0745 Fairfield, opp South Worcestershire College 0748 Fairfield, adj Cheltenham Road 0738 0750 0752 0852 0952 1052 1152 1252 1352 1452 1452 1552 1554 1552 1652 1752 Hinton Cross, Hinton Cross (S-bound) 0743 0757 0857 0957 1057 1157 1257 1357 1457 1457 1557 1559 1557 1657 1757 Hinton on the Green, Bevens Lane (N-bound) 1603 1559 Sedgeberrow, Winchcombe Road (SE-bound) 0746 0900 1100 1300 1500 1600 1604 1700 Sedgeberrow, adj Queens Head 0747 0901 1101 1301 1501 1601 1605 1701 Sedgeberrow, opp Churchill Road 0750 0904 1104 1304 1504 1604 1608 1704 Sedgeberrow, adj Hall Farm Drive 0800 1000 1200 1400 1500 1800 Ashton under Hill, opp Cross 0756 0804 0908 1004 1108 1204 1308 1404 1504 1508 1608 1612 1708 1804 Ashton under Hill, adj Cornfield Way 0758 0804 0910 1004 1110 1204 1310 1404 1506 1510 1610 1614 1710 1804 Ashton under Hill, adj Bredon Hill Middle School 0800 0800 1510 Beckford, opp Church 0808 0808 0916 1008 1116 1208 1316 1408 1516 1516 1616 1618 1716 1808 Little Beckford, Cheltenham Road (NE-bound) 0919 1319 Beckford, opp Church 0923 1323 1616 Conderton, opp Shelter -

8.4 Sheduled Weekly List of Decisions Made

LIST OF DECISIONS MADE FOR 09/03/2020 to 13/03/2020 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order Application No: 20/00090/TPOA Location: The Manor House, 4 High Street, Badsey, Evesham, WR11 7EW Proposal: Horsechestnut - To be removed. Reason - Roots are blocking the drains, tree has been pollarded in the past so is a bad shape and it is diseased. Applicant will plant another tree further from the house. Decision Date: 11/03/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Ms Elizabeth Noyes Agent: Ms Elizabeth Noyes The Manor House The Manor House 4 High Street 4 High Street Badsey Badsey Evesham Evesham WR11 7EW WR11 7EW Parish: Badsey Ward: Badsey Ward Case Officer: Sally Griffiths Expiry Date: 11/03/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565308 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 20/00236/HP Location: Hopwood, Prospect Gardens, Elm Road, Evesham, WR11 3PX Proposal: Extension to form porch Decision Date: 13/03/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mr & Mrs Asbury Agent: Mr Scott Walker Hopwood The Studio Prospect Gardens Bluebell House Elm Road Station Road Evesham Blackminster WR11 3PX Evesham WR11 7TF Parish: Evesham Ward: Bengeworth Ward Case Officer: Oliver Hughes Expiry Date: 31/03/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565191 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Page 1 of 17 Application No: 20/00242/ADV Location: Cavendish Park Care Home, Offenham Road, Evesham, WR11 3DX Proposal: Application -

The Parish Magazine Takes No Responsibility for Goods Or Services Advertised

Ashton-under-Hill The Beckford Overbury Parish Alstone & Magazine Teddington July 2018 50p Quiet please! Kindly don’t impede my concentration I am sitting in the garden thinking thoughts of propagation Of sowing and of nurturing the fruits my work will bear And the place won’t know what’s hit it Once I get up from my chair. Oh, the mower I will cherish, and the tools I will oil The dark, nutritious compost I will stroke into the soil My sacrifice, devotion and heroic aftercare Will leave you green with envy Once I get up from my chair. Oh the branches I will layer and the cuttings I will take Let other fellows dig a pond, I shall dig a LAKE My garden – what a showpiece! There’ll be pilgrims come to stare And I’ll bow and take the credit Once I get up from my chair. Extracts from ‘When I get Up From My Chair’ by Pam Ayres Schedule of Services for The Parish of Overbury with Teddington, Alstone and Little Washbourne, with Beckford and Ashton under Hill. JULY Ashton Beckford Overbury Alstone Teddington 6.00 pm 11.00 am 1st July 8:00am 9.30 am Evening Family 5th Sunday BCP HC CW HC Prayer Service after Trinity C Parr Clive Parr S Renshaw Lay Team 6.00 pm 11.00 am 9.30 am 8th July 9.30 am Evening Morning Morning 6th Sunday CW HC Worship Prayer Prayer after Trinity S Renshaw R Tett S Renshaw Roger Palmer 11.00 am 6.00 pm 15th July 9.30 am 8.00 am Village Evening 7th Sunday CW HC BCP HC Worship Prayer after Trinity M Baynes M Baynes G Pharo S Renshaw 10.00 am United Parish 22nd July CW HC 8th Sunday & Alstone after Trinity Patronal R Tett 29th July 10:30am 9th Sunday Bredon Hill Group United Worship after Trinity Overbury AUGUST 6.00 pm 5th August 8.00 am 9.30 am Evening 10th Sunday BCP HC CW HC Prayer after Trinity S Renshaw S Renshaw S Renshaw Morning Prayers will be said at 8.30am on Fridays at Ashton. -

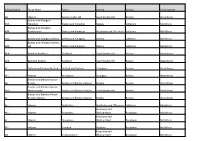

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency AA - <None> Ashton-Under-Hill South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABA - Aldington Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABB - Blackminster Badsey and Aldington Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs ABC - Badsey and Aldington Badsey Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington Bowers ABD - Hill Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs ACA - Beckford Beckford Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs ACB - Beckford Grafton Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs AE - Defford and Besford Besford Defford and Besford Eckington Bredon West Worcs AF - <None> Birlingham Eckington Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AH - Bredon Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AHA - Westmancote Bredon and Bredons Norton South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AI - Bredons Norton Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs AJ - <None> Bretforton Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs Broadway and AK - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AL - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs AP - <None> Charlton Fladbury Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AQ - <None> Childswickham Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Honeybourne and ARA - <None> Bickmarsh Pebworth Littletons Mid Worcs ARB - <None> Cleeve Prior The Littletons Littletons Mid Worcs Elmley Castle and AS - <None> Great Comberton Somerville -

Woodground Farm, Stock Green, Redditch, Worcestershire, B96 6TA 01562 820880 WOODGROUND FARM

Woodground Farm, Stock Green, Redditch, Worcestershire, B96 6TA 01562 820880 WOODGROUND FARM STOCK GREEN, REDDITCH, WORCESTERSHIRE, B96 6TA Droitwich 7 miles—Worcester 12 miles - Birmingham 24 miles (All distances approximate) BEAUTIFULLY SITUATED SMALL HOLDING, COMPRISING: Three bedroom farmhouse in need of extensive rebuild/renovation Traditional farm buildings, cattle yard and dutch barn Permanent grassland In all approximately 12.49 acres FOR SALE BY PUBLIC AUCTION ON WEDNESDAY 6TH APRIL 2016 AT 6.00 PM AT STONE MANOR HOTEL, KIDDERMINSTER, WORCESTERSHIRE, DY10 4PJ Sole Agents: Vendor’s Solicitors: Halls Holdings Ltd Mr T Baxter Esq Gavel House Taylors Solicitors 137 Franche Road 1 Mason Road Kidderminster Headless Cross Worcestershire Redditch DY11 5AP B97 5DA Tel: 01562 820880 Tel: 01527 544221 FOR SALE FOR SALE BY PUBLIC AUCTION GUIDE PRICE: £350,000 4 reception 3 bedrooms 1 bath rooms 12.49 Acres of land rooms Situation Description The farmhouse currently offers two storey Woodground Farm is situated in the idyllic rural Woodground farm offers a rare opportunity to accommodation with fixed wooden stair to loft Hamlet of Stock Green. The location is convenient purchase a ring fenced small holding comprising area. for commuting to Birmingham, Worcester, the of a farmhouse in need of rebuild/refurbishment, national motorway network and the facilities of the farm buildings and grassland, in all approximately nearby towns of Bromsgrove, Droitwich Spa, 12.49 acres. Stratford upon Avon and Redditch. Woodground Farmhouse Woodground farmhouse requires comprehensive rebuild/refurbishment but has huge potential to create a superb rural property (subject to the necessary planning consents). Directions From the B4090 Hanbury to Feckenham road turn right onto Church Road sign posted towards Bradley Green, at the end of the road turn left onto Dark Lane signposted towards Stock Wood, at the end of the road turn right and the property will be situated on your left as indicated by the agents For The farmhouse has many character features such Sale Board. -

Choice Plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 3 Home HOME Choice CHOICE .ORG.UK Plus PLUS

home choice plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 3 Home HOME Choice CHOICE .ORG.UK Plus PLUS ‘Working in partnership to offer choice from a range of housing options for people in housing need’ home choice plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 4 The Home Choice Plus process The Home Choice Plus process 2 What is a ‘bid’? 8 Registering with Home Choice plus 3 How do I bid? 9 How does the banding system work? 4 How will I know if I am successful? 10 How do I find available properties? 7 Contacts 11 What is Home Choice Plus? Home Choice Plus has been designed to improve access to affordable housing. The advantage is that you only register once and the scheme allows you to view and bid on available properties for which you are eligible across all of the districts. Home Choice Plus has been developed by a number of Local Authorities and Housing Associations working in partnership. Home Choice Plus is a way of allocating housing and advertising other housing options across the participating Local Authority areas. (Home Choice Plus will also be used for advertising other housing options such as private rents and intermediate rents). This booklet explains how to look for housing across all of the Districts involved in this scheme. Please see website for further information. Who is eligible to join the Home Choice Plus register? • Some people travelling to the United Kingdom are not entitled to Housing Association accommodation on the basis of their immigration status. • You may be excluded if you have a history of serious rent arrears or anti social behaviour. -

Evesham to Pershore (Via Dumbleton & Bredon Hills) Evesham to Elmley Castle (Via Bredon Hill)

Evesham to Pershore (via Dumbleton & Bredon Hills) Evesham to Elmley Castle (via Bredon Hill) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 19th July 2019 15th Nov. 2018 07th August 2021 Current status Document last updated Sunday, 08th August 2021 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2018-2021, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Evesham to Pershore (via Dumbleton and Bredon Hills) Start: Evesham Station Finish: Pershore Station Evesham station, map reference SP 036 444, is 21 km south east of Worcester, 141 km north west of Charing Cross and 32m above sea level. Pershore station, map reference SO 951 480, is 9 km west north west of Evesham and 30m above sea level. -

Sedgeberrow Mill Winchcombe Road • Sedgeberrow • Evesham • Worcestershire Sedgeberrow Mill Winchcombe Road • Sedgeberrow Evesham • Worcestershire

Sedgeberrow Mill Winchcombe Road • SedgebeRRoW • eveSham • WoRceSteRShiRe Sedgeberrow Mill Winchcombe Road • SedgebeRRoW eveSham • WoRceSteRShiRe Fascinating Grade II listed converted mill with ancillary accommodation in a village location Accommodation and Amenities Reception Hall • Sitting room • Mill room • Kitchen Dining room • Drawing room • Master bedroom Family bathroom • 3 Further bedrooms • Cloakroom Separate 1 bedroom self contained cottage Double garage • Stables • Paddock area In all about 0.08 hectare (0.2 acre) Evesham Railway station 4 miles (trains to London Paddington from 101 minutes) • Evesham 3 miles Cheltenham 12 miles • Chipping Campden 12 miles Stratford upon Avon 18 miles • Worcester 18 miles M5 (J9) 8 miles (distances and time approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. 1 bedroom cottage Situation • The parish of Sedgeberrow is surrounded by open countryside property is listed Grade II as being of Special Architectural or • Further living accommodation is found on the first floor located south of the market town of Evesham Historic Interest containing the kitchen, dining room and drawing room. An • Sedgeberrow itself benefits from numerous local amenities • The property is approached via a shared private drive with original mill stone is found in the dining room including a public house, village shop and a well regarded the house to the left and private parking opposite, in front of • The second floor benefits from a spacious landing with the primary school recently rated by Ofstead as outstanding. There the paddock. -

Converted from C:\PCSPDF\PCS63804.TXT

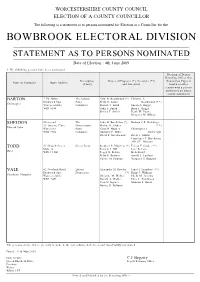

WORCESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR The following is a statement as to persons nominated for Election as a Councillor for the BOWBROOK ELECTORAL DIVISION __________________________________________ STATEMENT__________________________________________ AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED Date of Election : 4th June 2009 1. The following persons have been nominated Decision of Deputy Returning Officer that Description Names of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) Nomination Paper is Name of Candidate Home Address (if any) and Assentors Invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated BARTON 7 The Butts The Labour Colin R. Beardwood (*) Christine C. Droitwich Spa Party Philip G. Lamb Beardwood (**) Christopher Worcestershire Candidate Sharon J. Lamb Susan A. Briggs WR9 8SW John E. Smith Brian F. Briggs Shirley F. Smith Frank W. Payne Margaret M. Billings SHELDON Overmead The John H. Brackston (*) Barbara J.E. Meddings 23 Lucerne Close Conservative Michael L. Oakes (**) Edward John Worcester Party Carol H. Hughes Christopher J. WR3 7NA Candidate Anthony P. Miller Hartwright David T. Greenwood David J. Morris Constance J. Brackston Alfred L. Dawson TODD 52 Church Street Green Party Stephen P. Mayhew (*) Teresa F. Croke (**) Malvern Patricia L. Hill June R. Lane Dave WR14 1NH Peggy K. Belton Br Ackroyd Philip E. Bottom Arnold L. Ludford Valerie M. Dobson Margaret E. Buggins VALE 62 Newland Road Liberal Alexandra M. Rowley Janet I. Saunders (**) Droitwich Spa Democrats (*) Philip J. Williams Stephanie Margaret Worcestershire Christine M. Walker Sheila M. Jarrams WR9 7AZ Donald A. Walker Clare J. Tomlinson Vera N. Ingram Miranda F. Harris Norma D. Williams The persons above, where no entry is made in the last column, have been and stand validly nominated. -

Tewkesbury Community Connector

How much will it cost? 630 £1.50 adult return and £1.00 child up to 16 return on Tewkesbury Community Connector. £1.80 adult return on service 540 to Evesham. Tewkesbury £3.20 adult return on service D to Cheltenham. Please note: through ticketing unavailable at present. Fares to be paid to the connecting service driver and not Community to Tewkesbury Community Connector drivers. Contact details Holders of concessionary bus passes can travel free. To book your journey on Tewkesbury Connector Community Connector and for more How to book information please contact Third Sector To book your journey, simply call Third Sector Services Services on 0845 680 5029 on 0845 680 5029 between 8.00am and 4.00pm on the day before you travel. The booking line is open Monday Third Sector Services, Sandford Park Offices to Friday. You can also tell the Tewkesbury Community College Road, Cheltenham, GL53 7HX Connector driver when you next want to travel. www.thirdsectorservices.org.uk Please book by Friday of the previous week if you require transport on Saturday or Monday. When you book you will need to specify the day required, which village to pick you up from and where you intend to travel. You will be advised of the pick up place and time. Please note: the vehicle may arrive up to 10 minutes before or 10 minutes after the agreed time. Introducing a new community transport service for Tewkesbury Borough Operated by Third Sector Services in partnership with Gloucestershire County Council Further information Some journeys on service 606 will now serve Alderton and Gretton. -

Vlorcestershire. [ KELLY's

436 MAR VlORCESTERSHIRE. [ KELLY'S MARKET GARDENERs-eontinued. Jone~ Richard, Gt. Comberton,Pershre Nash John, Broughton, Pershore Hazlewood J. Eachway, Lickey, Barnt Jones Rbt. I 8wan la. Evesham New J.The Leys,Bengeworth,Ev('sbam Green 8.0 Jones William, Eckington, Pershore Newbury William, The Acers, North- Hazlewood William, Lydiate ash, Jones William, Grimley, Worcester wick road, Barbourne, Worcester Lickey, Bromsgrove Jordan J.The Green,Hampton,Eveshm Nickson J. Mucklow,Franche,Kdrmstr Healey Wm. Catshill, Bromsgrove Keen Henry, Badsey, Evesham Kunn Wm. Church Lench, Evesham Heath Mrs. A. Aldington, Evesham Keen John, Badsey, Evesham Oakley William, Pinvin, Pershore Heath Joseph, Wadborough, Kemp- Keen Richard, Badsey, Evesham Osborn Miss Martha, Draycot, Kemp- sey, Worcester Keen William, Badsey, Evesham sey, Worcester Hefford George, Henwick road, St. Kendal J. Lickey end, Lickey.Bmsgve Osborne G. jun. Bewdley st. Evesham John's, Worcester Keyte Charles, Badsey, Evesham Osborne Thomas, IQ Elm road, Benge- Heming R. North Littleton, Evesham Keyte John, Badsey, Evesham worth, Evesham Hemming William, Newland,Pershore Keyte John, jun. Badsey, Evesham Osborne Wm. Habberley, Kiddermnstr Herbert James, Badsey, Evesham Keyte William, Badsey, Evesham Palfrey Thos. High street, Pershore Herbert Thomas, The Leys, Benge- Kings Jsph. Lickey end, Bromsgrove Palmer Reuben, Cookhill, Alcester worth, Evesham Kings Thomas, High street, Pershore RS.O. (Warwickshire) Heritage Alfred, The Leys, Benge- Knight Albt. Victoria ay. Evesham Parish :Mrs. C. Eckington, Pershore worth, Evesham Knight A. T. Victoria ay. Evesham Payne Charles, Broadway R.S.O Hiden William, 23 Cowl st. Evesham Knight Charles, Badsey, Evesham Pearce George, Station road, Pershore Higgs Henry, Blakebrook, Kiddermstr Knight Edwin, Badsey, Evesham Pearman Herbert, Netherfields, Bad- Hill Geo. -

South Worcestershire Councils Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment

South Worcestershire Councils Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Final Report August 2019 www.jbaconsulting.com South Worcestershire Councils This page is intentionally left blank 2018s1367 - South Worcestershire Councils - Level 1 SFRA Final Report v1.0.docx ii JBA Project Manager Joanne Chillingworth The Library St Philips Courtyard Church Hill Coleshill Warwickshire B46 3AD Revision history Revision Ref/Date Amendments Issued to Draft Report v1.0/ Draft Report Angie Matthews December 2018 (Senior Planning Officer) Draft Report v2.0/May Addition of cumulative impact Angie Matthews 2019 assessment, updated report layout (Senior Planning Officer) Final Report v1.0/August Addressed stakeholder comments Angie Matthews 2019 (Senior Planning Officer) Contract This report describes work commissioned by the South Worcestershire Councils (Wychavon District Council, Malvern Hills District Council and Worcester City Council), by an email dated 12th October 2018 from Wychavon District Council. Lucy Finch of JBA Consulting carried out this work. Prepared by .................................. Lucy Finch BSc Analyst Reviewed by .................................. Joanne Chillingworth BSc MSc MCIWEM C.WEM Principal Analyst Hannah Coogan BSc MCIWEM C.WEM Technical Director Purpose This document has been prepared as a Final Report for the South Worcestershire Councils (Malvern Hills District Council, Wychavon District Council and Worcester City Council). JBA Consulting accepts no responsibility or liability for any use that is made of this document