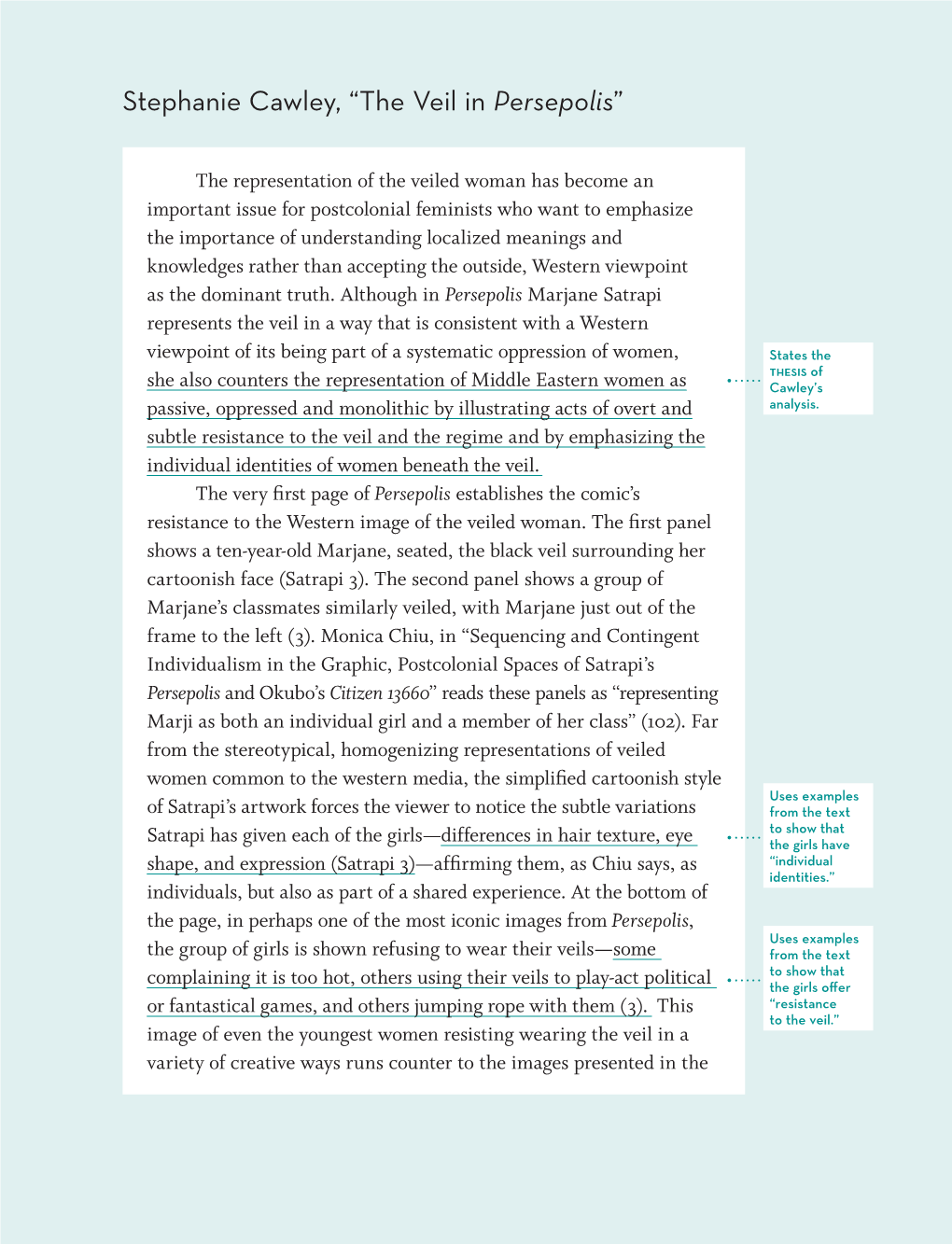

Stephanie Cawley, “The Veil in Persepolis”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discursive Construction of Referential Truth in Art Spiegelman's Maus And

The Comic Book as Complex Narrative: Discursive Construction of Referential Truth in Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis By Hannah Beckler For honors in The Department of Humanities Examination Committee: Annjeanette Wiese Thesis Advisor, Humanities Paul Gordon Honors Council Representative, Humanitities Paul Levitt Committee Member, English April 2014 University of Colorado at Boulder Beckler 2 Abstract This paper addresses the discursive construction of referential truth in Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. I argue that referential truth is obtained through the inclusion of both correlative truth and metafictional self-reflection within a nonfictional work. Rather than detracting from their obtainment of referential truth, the comic book discourses of both Maus and Persepolis actually increase the degree of both referential truth and subsequent perceived nonfictionality. This paper examines the cognitive processes employed by graphic memoirs to increase correlative truth as well as the discursive elements that facilitate greater metafictional self-awareness in the work itself. Through such an analysis, I assert that the comic discourses of Maus and Persepolis increase the referential truth of both works as well as their subsequent perceived nonfictionality. Beckler 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………….4 2. Part One: Character Recognition and Reader Identification in Images……..7 3. Part Two: Representing Space, Time, and Movement……………………..15 4. Part Three: Words and Images……………………………………………..29 5. Part Four: The Problem of Memory in Representation……………...……..34 6. Part Five: Subjective Reconstruction and Narration……………………….48 7. Conclusion………………………………………………………………….56 Works Cited………………………………………………………………...60 Beckler 4 Although comic books are often considered a lower medium of literary and artistic expression compared to works of literature, art, or film, modern graphic novels often challenge the assumption that such a medium is not capable of communicating complex and nuanced stories. -

Teacher Resource Packet for Vietnamese Students. INSTITUTION Washington Office of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Olympia

)xocliMENTRESUME ,ED 118 679 UD 015 707 TITLE- Teacher Resource Packet for Vietnamese Students. INSTITUTION Washington Office of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Olympia. PUB DATE Jul 75 NOTE'-. litp.; This document is available in microfiche only 'due to the print size of parts of the original 0 document EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Asian Americans; Bilingual Education; *Bilingual Students; Educational. Resources; Elementary School Students; English (Second Language); *Ethnic Groups;, Guidelines; Immigrants; *Indo hinese; Minority Group Children; Minority Groups; *Re ugees; Resource Guides; Resource Materials; Se ndary School Students; *Student Characterist cs;- Student Needs; Student Problems; Student TeacheRelationship; Teacher Guidance; Teacher Respons bility IDENTIFIERS *Vietnam r ABSTRACT This packet provides information for classroom , teachers who will be working with Vietnamese students Among the subject matter discussed in the history and general in ormation section are the Republic of Vietnam, family loyalty, p ofessional man, politeness and restraint, village life, fruits and vegetables, meat dishes, festivals, and religion. Other sections include a summary of some cultural differences, a Vietnamese language guide, and Asian immigrant impressions. A section on bilingual education information discus es theory, definition, and the legal situation concerning bilingu4lism and English as a second language. Suggestions for interacting with non-English dominant students in all grade levels in either a regular classroom setting or a secondary school setting are provided. Relevant resources, such as materials that can be used for basic instruction in English (as a second language) classes, reading resources, and community resources are enclosed. (Author/AM) **********L********************************************************* Documents acquired by ERIlinclude many informal unpublished * materials not aotailable from ther sources. -

Human Rights of Women Wearing the Veil in Western Europe

Human Rights of Women Wearing the Veil in Western Europe Research Paper I. Introduction The present paper analyses legislation, policies, and case-law surrounding religious attire in a number of countries in Western Europe and how they affect the human rights of women and girls who wear the veil in Western Europe. It also more broadly analyses discrimination and violence experienced by women wearing the veil in Europe learning from their own voice. Throughout the paper, the terminology ‘veil’ is used to refer to a variety of religious attire worn mostly, but not exclusively, by Muslim women. There are different types of clothing that cover the body. This research is focused on manifestations of veils that are the subject of regulation in several Western European Countries. They include the hijab (a piece of clothing that covers the head and neck, but not the face), niqab (a piece of clothing that covers the face, where only the eyes are visible), burqa (a piece of clothing that covers both the face and eyes), jilbab (a loose piece of clothing that covers the body from head to toe), or abaya, kaftan, kebaya (a loose, often black, full body cover overcoat). The head and body covers are often combined. In several countries, some of these clothing are based on traditional costumes rather than religion and are often worn by rural communities in the countries of origins. The paper also uses the terminology ‘full-face veil’ or ‘face-covering veil’ to refer to both niqab and burqa. Furthermore, it refers to burkini, a swimsuit that covers the body from head to ankles, completed by a dress. -

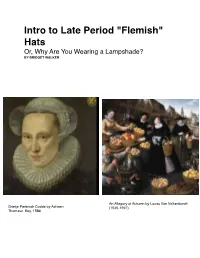

"Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? by BRIDGET WALKER

Intro to Late Period "Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? BY BRIDGET WALKER An Allegory of Autumn by Lucas Van Valkenborch Grietje Pietersdr Codde by Adriaen (1535-1597) Thomasz. Key, 1586 Where Are We Again? This is the coast of modern day Belgium and The Netherlands, with the east coast of England included for scale. According to Fynes Moryson, an Englishman traveling through the area in the 1590s, the cities of Bruges and Ghent are in Flanders, the city of Antwerp belongs to the Dutchy of the Brabant, and the city of Amsterdam is in South Holland. However, he explains, Ghent and Bruges were the major trading centers in the early 1500s. Consequently, foreigners often refer to the entire area as "Flemish". Antwerp is approximately fifty miles from Bruges and a hundred miles from Amsterdam. Hairstyles The Cook by PieterAertsen, 1559 Market Scene by Pieter Aertsen Upper class women rarely have their portraits painted without their headdresses. Luckily, Antwerp's many genre paintings can give us a clue. The hair is put up in what is most likely a form of hair taping. In the example on the left, the braids might be simply wrapped around the head. However, the woman on the right has her braids too far back for that. They must be sewn or pinned on. The hair at the front is occasionally padded in rolls out over the temples, but is much more likely to remain close to the head. At the end of the 1600s, when the French and English often dressed the hair over the forehead, the ladies of the Netherlands continued to pull their hair back smoothly. -

Mantilla Veil NHV Winners and More

Issue 113 - August 2015 This month... Next Issue: August 19th, 2015 Marketing Hats Caren Lee Make a Mantilla Veil NHV Winners And More... the e-magazine for those who make hats Issue 113 August 2015 Contents: The Hatwalk 2 SJ Brown’s advice for marketing millinery on fashion weeks’ runways. Hat of the Month 6 A Melbourne Cup piece by Caren Lee. Make a Shoulder Length Mantilla Veil 8 A tutorial by Denise Innes-Spencer of The British School of Millinery. The NHV Hat Contest 19 The Dutch Hat Association’s 2015 competition winners. Letter to the Editor 24 Advice on applying stiffener. The Back Page 25 Royal Ascot 2015, HATalk Give Away and how to contact us. Cover/Back Pages: 1 www.hatalk.com Head wear by Denise Innes The Hatwalk: Marketing millinery on fashion weeks’ runways Not every country can boast a ‘Hat handing out thousands of business Week’ like England. As a milliner in cards. Still, I was getting nowhere. the United States, I wish there was a So, how does a milliner sell hats New York Hat Week or Chicago Hat in a country where hats are not so Week, but no such luck. Until those commonplace? As with any good cities take the cue from London and marketing plan, you have to know create their own Hat Weeks, I will be your audience. perfectly content just crashing the party on my local runway. After trying all the normal marketing ploys, I realized the normal American Why am I crashing the ‘fashion week’ woman is not my target audience. -

December 18, 1953

Temple !3 e tl1,-El 6S8 Bro~d St . R. :L~.--------. Rhode lslond's Only Anglo-Jewish Greotest Newspoper Independent In Weekly The JewisffHl'fiJa Rhode Island VOL. XXXVIIl, No. 42 FRIDAY, DECEMBER 18, 1913 PROVIDENCE, R. I TWELVE PAGES 10 CENTS THE COPY Prevention, Control of Family l'roblems to , Be Study Project Technion Starts Capital NEW YORK-Three. American of St. Paul and the Rosenberg communities. each typical of its Foundation of San Francisco. The $100,000 Fund Campaign type, but widely separated as to three new projects will be under geographic location, population, way by January, 1954, and will history and pe-rsonality, have been help check findings concerning selected by the Community Re social problem patterns which Fain, Weisberg search Associates, Inc., to test and were uncovered in the Community demonstrate methods of preven Research Associates' original St. tion and control of family prob Paul study. To Head Drive lems in a new million dollar, four Out of the original study by year project. Community. Research Associates Joseph W. Wunsch, national From East to West. the three are came the startling fact that about president of the American Tech~ Hagerstown, Md., with a popUla six per cent of the population were nton Society, announced today tion of 70.000 and a great h istori absorbing well over half of all that Irving Jay Fain and Mark cal tradition; Winona, Minn., health and welfare funds, both Weisberg have accepted the co typical mid-western town with a public and voluntary. ch airmanship of the Southern New population cf 40,000; and San England Chapter of the American Mateo, Cal., comparatively new Multi-Problem Patterns Technion Society's Capital Fund and fast - growing metropolitan Further, it disclosed that more Campaign. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

Autobiographies: Psychoanalysis and the Graphic Novel

AUTOBIOGRAPHIES: PSYCHOANALYSIS AND THE GRAPHIC NOVEL PARASKEVI LYKOU PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE JANUARY 2014 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the conjunction of the graphic novel with life- writing using psychoanalytic concepts, primarily Freudian and post- Freudian psychoanalysis, to show how the graphic medium is used to produce a narrative which reconstructs the function of the unconscious through language. The visual language is rich in meaning, with high representational potential which results in a vivid representation of the unconscious, a more or less raw depiction of the function of the psychoanalytic principles. In this project I research how life-writing utilises the unique representational features of the medium to uncover dimensions of the internal-self, the unconscious and the psyche. I use the tools and principles of psychoanalysis as this has been formed from Freud on and through the modern era, to propose that the visual language of the graphic medium renders the unconscious more accessible presenting the unconscious functionality in a uniquely transparent way, so that to some extent we can see parts of the process of the construction of self identity. The key texts comprise a sample of internationally published, contemporary autobiographical and biographical accounts presented in the form of the graphic novel. The major criterion for including each of the novels in my thesis is that they all are, in one way or another, stories of growing up stigmatised by a significant trauma, caused by the immediate familial and/or social environment. Thus they all are examples of individuals incorporating the trauma in order to overcome it, and all are narrations of constructing a personal identity through and because of this procedure. -

Kate Warren, “Persepolis: Animation, Representation and the Power of the Personal Story,” Screen Education, Winter 2010, Issue 58, PP

Kate Warren, “Persepolis: Animation, Representation and the Power of the Personal Story,” Screen Education, Winter 2010, Issue 58, PP. 117-23. Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis {2007), based on her graphic novels of the same name, is one of a growing number of films thiat employs formats such as animation, which is traditionally aimed at younger audiences, to depict complex and confronting subject matter. In doing so, such films offer interesting avenues of investigation for students and educators, not only in terms of the stories told, but also in relation to how these artistic and aesthetic techniques affect the narrative structures and modes of representation offered. Author, illustrator and filmmaker Marjane Satrapi was born in Rasht, Iran, in 1969.' As a child she witnessed one of the most dramatic periods in her country's recent history: the overthrow of the shah in 1979, the subsequent Islamic Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War. The film Persepolis charts her childhood in Tehran, her secondary education in Vienna and her tertiary studies in Iran, and concludes with her decision to leave Iran permanently for France. The formative years of childhood, adolescence and early adulthood are negotiated during a period of great flux and trauma for her country, her family and herself. Through her graphic novels and this film, Satrapi depicts these events and experiences with frankness, humour, poignancy and emotional power. Questions of representation When approaching cultural and historical traumas - such as war, revolution and genocide - questions are often raised about how these events are to be represented, who is 'entitled' to represent them, and whether they should be represented at all. -

Chicken with Plums

CHICKEN WITH PLUMS a film by Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud Adapted from the graphic novel Chicken with Plums by Marjane Satrapi Venice International Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 Tribeca Film Festival 2012 91 min | Language: French (with English subtitles) East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Tami Kim Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS Teheran, 1958. Since his beloved violin was broken, Nasser Ali Khan, one of the most renowned musicians of his day, has lost all taste for life. Finding no instrument worthy of replacing it, he decides to confine himself to bed to await death. As he hopes for its arrival, he plunges into deep reveries, with dreams as melancholic as they are joyous, taking him back to his youth and even to a conversation with Azraël, the Angel of Death, who reveals the future of his children... As pieces of the puzzle gradually fit together, the poignant secret of his life comes to light: a wonderful story of love which inspired his genius and his music... DIRECTORS’ STATEMENT By Marjane Satrapi & Vincent Paronnaud Chicken with Plums is the story of a famous musician whose prized instrument has been ruined. -

Hat, Cap, Hood, Mitre

CHAPTER 1 Headgear: Hat, Cap, Hood, Mitre Introduction down over his shoulders;4 and in Troilus and Criseyde Pandarus urges his niece, a sedate young widow, to Throughout the later Middle Ages (the twelfth to early cast off her face-framing barbe, put down her book and sixteenth centuries), if we are to believe the evidence of dance.5 art, some kind of headgear was worn by both sexes in- In art of the middle medieval period (from about doors and out: at dinner, in church, even in bed. This is the eighth to the eleventh centuries), headgear is less understandable if we consider the lack of efficient heat- well attested. Men are usually depicted bareheaded. ing in medieval buildings, but headgear was much more Women’s heads and necks are wrapped in voluminous than a practical item of dress. It was an immediate mark- coverings, usually depicted as white, so possibly linen is er of role and status. In art, it is possible to distinguish being represented in most cases. There is no clue to the immediately the head of a man from that of woman, as shape of the piece of cloth that makes up this headdress, for example in a fourteenth-century glass panel with a sa- how it is fastened, or whether there is some kind of cap tirical depiction of a winged serpent which has the head beneath it to which it is secured. Occasionally a fillet is of a bishop, in a mitre, and a female head, in barbe* and worn over, and more rarely under, this veil or wimple. -

Women in the Middle East – Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis Recommended

Women in the Middle East – Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis Recommended Use: This unit was developed for an Introduction to Human Rights class that was taught online. It was part of a module on Women’s Rights and was preceded by a module on group rights in general and information on the history of Women’s Rights. Use in any level human rights class or women’s rights class. The format works for both the original online setting as well as in offline classes. Keywords: Women’s Rights, Middle East, Persepolis, discrimination, stereotypes, Islam, graphic novel Objectives: Students will be able to reflect on the topic of women’s rights (in Iran). Students will be able to compare one or more news articles to the Iranian graphic novel Persepolis. They will be able to formulate a standpoint and recognize biases/constructions in media. Reading(s)/ Material(s): - Marjane Satrapi. Persepolis. The Story of a Childhood. (ISBN: 978-0375714573) - One or more recent articles that provide an outside view of women in the Middle East (e.g. Hubbard, Ben. “Saudi Women Rise Up Quietly.” New York Times. Web. 10/27/2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/27/world/middleeast/a-mostly-quiet-effort-to-put-saudi- women-in-drivers-seats.html?_r=0) Synopsis: Persepolis is Marjane Satrapi’s memoir of growing up in Iran during the Islamic Revolution. Satrapi tells the story of her life in Tehran from ages six to fourteen, years that saw the overthrow of the Shah’s regime, the triumph of the Islamic Revolution, and the devastating effects of war with Iraq.