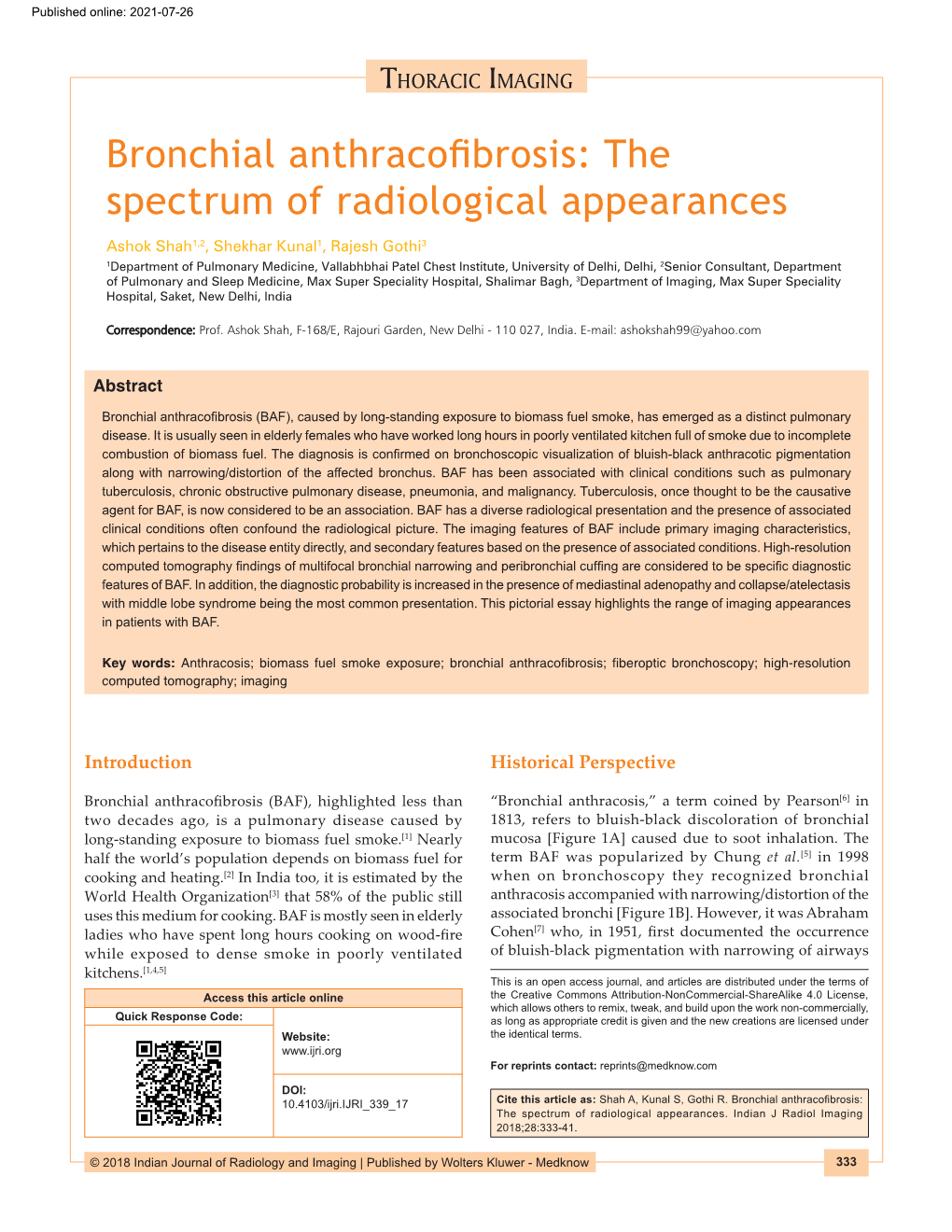

Bronchial Anthracofibrosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chest Radiology: a Resident's Manual

Chest Radiology: A Resident's Manual Bearbeitet von Johannes Kirchner 1. Auflage 2011. Buch. 300 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 13 153871 0 Format (B x L): 23 x 31 cm Weitere Fachgebiete > Medizin > Sonstige Medizinische Fachgebiete > Radiologie, Bildgebende Verfahren Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. 1 Heart Failure Acute left heart failure is most commonly caused by a hyperten- " Compare pulmonary vessels that are equidistant to a central sive crisis. Radiographic signs on the plain chest radiograph ob- point in the respective hilum. tained with the patient standing include: " Compare the diameter of a random easily identifiable superior " Redistribution of pulmonary perfusion lobe artery (often the anterior segmental artery is most easily " Presence of interstitial patterns (Kerley lines, peribronchial identifiable) with the diameter of the corresponding ipsilateral cuffing) bronchus (Fig. 1.62). " Alveolar densities with indistinct vascular structures (ad- vanced stage) As the pulmonary artery and corresponding ipsilateral bronchus " Pleural effusions are normally of precisely equal diameter, a larger arterial diameter is indicative of redistribution of perfusion (Fig. 1.63). The diagnos- All of these signs are essentially attributable to increased fluid tic criteria of caudal-to-cranial redistribution cannot be evaluated content in the abnormally heavy “wet” lung. The fluid accumula- on radiographs obtained in the supine patient. -

Common Pediatric Pulmonary Issues

Common Pediatric Pulmonary Issues Chris Woleben MD, FAAP Associate Dean, Student Affairs VCU School of Medicine Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics Objectives • Learn common causes of upper and lower airway disease in the pediatric population • Learn basic management skills for common pediatric pulmonary problems Upper Airway Disease • Extrathoracic structures • Pharynx, larynx, trachea • Stridor • Externally audible sound produced by turbulent flow through narrowed airway • Signifies partial airway obstruction • May be acute or chronic Remember Physics? Poiseuille’s Law Acute Stridor • Febrile • Laryngotracheitis (croup) • Retropharyngeal abscess • Epiglottitis • Bacterial tracheitis • Afebrile • Foreign body • Caustic or thermal airway injury • Angioedema Croup - Epidemiology • Usually 6 to 36 months old • Males > Females (3:2) • Fall / Winter predilection • Common causes: • Parainfluenza • RSV • Adenovirus • Influenza Croup - Pathophysiology • Begins with URI symptoms and fever • Infection spreads from nasopharynx to larynx and trachea • Subglottic mucosal swelling and secretions lead to narrowed airway • Development of barky, “seal-like” cough with inspiratory stridor • Symptoms worse at night Croup - Management • Keep child as calm as possible, usually sitting in parent’s lap • Humidified saline via nebulizer • Steroids (Dexamethasone 0.6 mg/kg) • Oral and IM route both acceptable • Racemic Epinephrine • <10kg: 0.25 mg via nebulizer • >10kg: 0.5 mg via nebulizer Croup – Management • Must observe for 4 hours after -

Radiologic Assessment in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

THE YALE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE 57 (1984), 49-82 Radiologic Assessment in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit RICHARD I. MARKOWITZ, M.D. Associate Professor, Departments of Diagnostic Radiology and Pediatrics, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut Received May 31, 1983 The severely ill infant or child who requires admission to a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) often presents with a complex set of problems necessitating multiple and frequent management decisions. Diagnostic imaging plays an important role, not only in the initial assessment of the patient's condition and establishing a diagnosis, but also in monitoring the patient's progress and the effects of interventional therapeutic measures. Bedside studies ob- tained using portable equipment are often limited but can provide much useful information when a careful and detailed approach is utilized in producing the radiograph and interpreting the examination. This article reviews some of the basic principles of radiographic interpreta- tion and details some of the diagnostic points which, when promptly recognized, can lead to a better understanding of the patient's condition and thus to improved patient care and manage- ment. While chest radiography is stressed, studies of other regions including the upper airway, abdomen, skull, and extremities are discussed. A brief consideration of the expanding role of new modality imaging (i.e., ultrasound, CT) is also included. Multiple illustrative examples of common and uncommon problems are shown. Radiologic evaluation forms an important part of the diagnostic assessment of pa- tients in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Because of the precarious condi- tion of these patients, as well as the multiple tubes, lines, catheters, and monitoring devices to which they are attached, it is usually impossible or highly undesirable to transport these patients to other areas of the hospital for general radiographic studies. -

Respiratory Distress in Pediatrics

Hindsight is 20/20 Karen A. Santucci, M.D. Professor of Pediatrics Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital October 9, 2014 Disclosure No Financial Relationships Personal Financial Disclosure Case 1 Toddler siblings are jumping on the couch Larger one lands on top of the smaller one, both landing on the tile floor The smaller child cries out and develops respiratory distress. 911 activated Vitals: RR 62, HR 168, afebrile, crying EMS is transports her to the nearest hospital Case Progression Upon arrival, oxygen saturation in 70’s and severe respiratory distress Supplemental oxygen not helping! Decreased breath sounds bilaterally! No reported tracheal deviation Difficult to ventilate and oxygenate! Bilateral chest tubes are placed! She’s Intubated! Still difficult to ventilate and oxygenate! Case Progression Differential Diagnoses? Differential Diagnoses? Pulmonary contusion? Traumatic pneumothorax? Hemothorax? Crush injury? Transection? Underlying problem????? -Asthma -Pneumonia -Cystic fibrosis Perplexing Case Pediatric Pearl If it doesn’t make sense, go back to the basics. What were they doing right before the fall? Something We Don’t See Everyday! or Do We???? What the Heck!! Epidemiology 92,166 cases reported to Poison Centers in 2003 Peak incidence 6 months to 3 years 600 children die annually Majority present to EDs 2003 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System Am J Emerg Med 2004; 22:335-404 Foreign Bodies Food Coins Toys Munchausen Syndrome by -

Post Lung Transplant Complications: Emphasis on CT Imaging Findings

Post Lung Transplant Complications: Emphasis on CT Imaging Findings Rashmi Katre, MD Carlos S Restrepo, MD Ameya Baxi, MD Learning Objectives • To identify the pulmonary complications and pathological processes which may occur after lung transplantation • To describe the role of imaging in post transplant patients with emphasis on the CT imaging findings of the select relevant entities None of the authors has any financial disclosure to make. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest Introduction • Lung transplantation has been widely accepted as a treatment of choice among patients with end stage lung disease. • Past experiences have shown its efficacy in improving the longevity as well as quality of life in many patients. Nevertheless, it is not devoid of complications which may vary from trivial and treatable entities to life threatening conditions. • The complications can be divided into plural, pulmonary and airway diseases such as; hyperacute, acute, and chronic rejection including bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia; pulmonary infections; bronchial anastomotic complications; pleural effusions; pneumothoraces, lung herniation, pulmonary thromboembolism; upper-lobe fibrosis; primary disease recurrence; posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder. • Imaging , especially CT is crucial in early detection, evaluation and diagnosis of these complications, in order to decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with certain conditions. This educational exhibit addresses the pathological processes after lung transplantation and discusses the role of imaging, with emphasis on CT imaging findings. Reperfusion Edema Ischemia-reperfusion injury is a noncardiogenic pulmonary edema that typically occurs more than 24 hours after transplantation, peaks in severity on postoperative day 4, and generally improves by the end of the 1st week. -

Pleural Effusion

1 เอกสารประกอบการสอน เรื่อง รังสีวิทยาระบบทางเดินหายใจ: การเลือกส่งตรวจและแปลผลภาพรังสีทรวงอก (Radiology of the chest: methods of investigation and plain film interpretation) โดย แพทย์หญิงวรรณพร บุรีวงษ์ 2 แผนการสอน หัวข้อ รังสีวิทยาระบบทางเดินหายใจ: การเลือกส่งตรวจและแปลผลภาพรังสีทรวงอก ผู้สอน พญ. วรรณพร บุรีวงษ์ เวลา 3 ชั่วโมง วัตถุประสงค์ เพื่อให้นิสิตแพทย์สามารถ 1. บอกวิธีการตรวจและข้อบ่งชี้ในการส่งตรวจทางรังสีวิทยาของระบบทางเดินหายใจได้ 2. บอกท่าที่ใช้ถ่ายภาพรังสีทรวงอก และความเหมาะสมของเทคนิคที่ใช้ในการถ่ายภาพได้ 3. สามารถอธิบายโครงสร้างและอวัยวะภายในของร่างกายที่พบบนภาพรังสีทรวงอกได้ เนื้อหาหัวข้อ 1. วิธีการตรวจทางรังสีวิทยาของระบบทางเดินหายใจ ได้แก่ Plain chest radiography (CXR), Computed tomography (CT), CT angiography, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Ultrasonography, Angiography และ Radionuclide study 2. ลักษณะทางกายวิภาคเบื้องต้นของระบบทางเดินหายใจ (Normal anatomy of the chest) 3. ภาพถ่ายรังสีทรวงอกแบบปกติ (Normal chest radiography) การจัดประสบการณ์เรียนรู้ 1. บอกวัตถุประสงค์และบอกเนื้อหา 5 นาที 2. สอนบรรยายหัวข้อต่างๆ 60 นาที 3. กิจกรรม/สอนแสดง 90 นาที 4. สรุปเนื้อหาบทเรียน 15 นาที 5. นิสิตซักถาม 10 นาที สื่อการสอน 1. เอกสารประกอบการสอน 2. Power point ทั้งภาพนิ่งและ animation 3. ภาพถ่ายทางรังสี วิธีประเมินผล 1. ข้อสอบ Multiple choice question 5 ตัวเลือก 2. ข้อสอบบรรยายภาพถ่ายทางรังสี OSCE 3 หนังสือและเอกสารอ้างอิง 1. Sutton D. Textbook of radiology and imaging. 6th ed. China: Churchill Living stone, 1998 2. Herring W. Learning radiology: recognizing the basics. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby, 2007. 3. Armstrong P, -

Peribronchial Cuffing Rather Than Consolidation Pneumonia Or Not? P-CXR

21.04.23 KSEM spring conference: Pediatric images, what we have to focus on P-CXR Essential viewpoints for pediatrics in ED1 Ajou Univ. School of Medicine Department of emergency medicine Jung Heon Kim P-CXR I have nothing to disclose .“Normal” chest AP .Pneumonia or not? .Appendix .Take-home message P-CXR Am I normal? “Normal” chest AP P-CXR My residents: “What (the hell) is normal chest AP?” The answer is… It is inherently difficult… Check expiration & rotation Why? Young kids (<4 y): poor cooperation when taking pictures “Normal” chest AP P-CXR . AP view: trapezoid thorax & horizontal ribs . Small-looking lungs - CT ratio: 60%–65% (false cardiomegaly) - Elevated diaphragm . False (+) findings - Thymus: look like mediastinal mass - Trachea: slightly Rt-deviated - Air bronchogram: bronchial branching around hilum . Lat view (optional): retrosternal “white” “Normal” chest AP P-CXR Check expiration & rotation Findings Expiration Diaphragm at 8th post rib or higher (cf, 6th ant. rib) Under-aerated (“whitish lung”) & Rt-deviated trachea Triangular hemi-thorax (ribs: oblique > horizontal) “Larger”-looking heart & thymus Rotation T-spinous proc is midway between 2 med ends of clavicles “Normal” chest AP P-CXR Expiration WIN! vs 8 8 th Diaphragm at slightly higher than 8 post rib ( Diaphragm at 9th post rib (5th ant rib) 4th ant rib) More trapezoid hemi-thorax Triangular hemi-thorax & larger heart “Normal” chest AP P-CXR Rotation WIN! vs Diaphragm at 8th post rib (6th ant rib) Diaphragm at 8th post rib (5th ant rib) Triangular hemi-thorax Trapezoid -

The Added Value of the Lateral Chest Radiograph for Diagnosing

,0$-ǯ92/20ǯ-$18$5<2018 ORIGINAL ARTICLES The Added Value of the Lateral Chest Radiograph for Diagnosing Community Acquired Pneumonia in the Pediatric Emergency Department Michalle Soudack MD1,3, Semion Plotkin MD2,3, Aviva Ben-Shlush MD1, Lisa Raviv-Zilka MD1,3, Jeffrey M. Jacobson MD1, Michael Benacon MD2,3 and Arie Augarten MD2,3 Departments of 1Pediatric Imaging and 2Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Safra Children’s Hospital, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer, Israel 3Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel nia (CAP), and a recent review reiterated and stressed the need ABSTRACT: Background: Opinions differ as to the need of a lateral radio- for both fontal and lateral views for infants and children with graph for diagnosing community acquired pneumonia in lower respiratory tract symptoms [1,2]. children referred to the emergency department. A lateral radio- The lateral chest radiograph assists in the localization and graph increases the ionizing radiation burden but at the same characterization of findings seen on the frontal view. Certain time may improve specificity and sensitivity in this population. “blind areas,” such as the retro-cardiac space, are better visual- Objectives: To determine the value of the frontal and lateral ized with the lateral view. However, despite the IDSA guide- chest radiographs compared to frontal view stand-alone images lines, opinions differ as to the need for the lateral view, in part for the management of children with suspected community due to the extra radiation exposure [2-9]. acquired pneumonia seen in a pediatric emergency department. In this study we aimed to determine the added value of the Methods: Chest radiographs from 451 children with clinically lateral chest radiograph for children with suspected CAP. -

Pediatric Surgery and Medicine for Hostile Environments

PEDIATRIC SURGERY AND MEDICINE FOR HOSTILE ENVIRONMENTS Kevin M. Creamer, MD • Michael M. Fuenfer, MD MY MEDI AR CA S L E D T E A P T A S R T D M E T E I N N T U B O E R T D TU EN INSTI Second Edition Pediatric Surgery and Medicine for Hostile Environments Second Edition Borden Institute US Army Medical Department Center and School Health Readiness Center of Excellence Fort Sam Houston, Texas Office of The Surgeon General United States Army Falls Church, Virginia i The test of the morality of a society is what it does for its children. —Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945) ii This book is dedicated to the military medical professional in a land far from home, standing at the bedside of a critically ill child. iii Dosage Selection: The authors and publisher have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of dosages cited herein. However, it is the responsibility of every practitioner to consult appropriate information sources to ascertain correct dosages for each clinical situation, especially for new or unfamiliar drugs and procedures. The authors, editors, publisher, and the Department of Defense cannot be held responsible for any errors found in this book. Use of Trade or Brand Names: Use of trade or brand names in this publication is for illustrative purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the Department of Defense. Neutral Language: Unless this publication states otherwise, masculine nouns and pronouns do not refer exclusively to men. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the personal views of the authors and are not to be construed as doctrine of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense. -

Download This PDF File

DIAGNOSE THIS A 45-Year-Old Male with New Onset Shortness of Breath Kristen Ralph MD, MSc1, Adam Dmytriw MD MSc2, Robert Miller MD3 1Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University 2Department of Medical Imaging, University of Toronto 3Department of Radiology, QEII Health Sciences Centre A 45 year-old male presented to the ED for the second time in one week, complaining of shortness of breath and low grade fever, taken at home with an oral What is the most likely diagnosis? thermometer. He had recently completed treatment for lymphoma. He denied chest pain, but admitted that A. Congestive heart failure he had noticed some new swelling in his legs. He was B. ARDS or shock lung admitted with a diagnosis of presumed pneumonia C. Lymphangitic carcinomatosis and rapidly deteriorated, requiring intubation 12 D. Acute pulmonary hemorrhage hours following admission to the ICU. A portable E. Bilateral pneumonia anteroposterior (AP) chest x-ray was taken to check placement of this tubes and lines (Figure 1). Figure 1. Anteriorposterior (AP) portable chest radiograph DMJ • Spring 2015 • 41(2) | 8 Diagnose This: Male with Shortness of Breath Answer configuration. The chest x-ray can also demonstrate or rule out other potential causes of the patient’s The correct answer is "A". symptoms. Chest x-ray has a moderate specificity of about 76-83% but has a low sensitivity of 67-68%.6 ARDS would be incorrect as it classically presents as bilateral, peripheral airspace disease. It is not The gold standard test for evaluating heart failure is lymphangitic carcinomatosis as this disease classically a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE). -

CHEST RADIOLOGY Patterns and Differential Diagnoses This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Any screen. Any time. Anywhere. Activate the eBook version of this title at no additional charge.rge. Expert Consult eBooks give you the power to browse and find content, view enhanced images, share notes and highlights—both online and offline. Unlock your eBook today. Visit Scan this QR code to redeem your 1 expertconsult.inkling.com/redeem eBook through your mobile device: 2 Scratch off your code 3 Type code into “Enter Code” box 4 Click “Redeem” 5 Log in or Sign up 6 Go to “My Library” It’s that easy! Place Peel Off Sticker Here For technical assistance: email [email protected] call 1-800-401-9962 (inside the US) call +1-314-447-8200 (outside the US) Use of the current edition of the electronic version of this book (eBook) is subject to the terms of the nontransferable, limited license granted on expertconsult.inkling.com. Access to the eBook is limited to the first individual who redeems the PIN, located on the inside cover of this book, at expertconsult.inkling.com and may not be transferred to another party by resale, lending, or other means. CHEST RADIOLOGY Patterns and Differential Diagnoses This page intentionally left blank Seventh Edition CHEST RADIOLOGY Patterns and Differential Diagnoses James C. Reed, MD Professor of Radiology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky 1600 John F. Kennedy Blvd. Ste 1800 Philadelphia, PA 19103-2899 CHEST RADIOLOGY: PATTERNS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES ISBN: 978-0-323-49831-9 SEVENTH EDITION Copyright © 2018 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. -

Pulmonary Edema: a Pictorial Review of Imaging Manifestations and Current Understanding of Mechanisms of Disease

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS Open Access Articles Open Access Publications by UMMS Authors 2020-10-30 Pulmonary Edema: A Pictorial Review of Imaging Manifestations and Current Understanding of Mechanisms of Disease Maria Barile University of Massachusetts Medical School Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/oapubs Part of the Radiology Commons, and the Respiratory Tract Diseases Commons Repository Citation Barile M. (2020). Pulmonary Edema: A Pictorial Review of Imaging Manifestations and Current Understanding of Mechanisms of Disease. Open Access Articles. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.ejro.2020.100274. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/oapubs/4404 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Articles by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. European Journal of Radiology Open 7 (2020) 100274 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect European Journal of Radiology Open journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ejro Pulmonary Edema: A Pictorial Review of Imaging Manifestations and Current Understanding of Mechanisms of Disease Maria Barile Department of Radiology at University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Pulmonary edema is a common clinical entity caused by the extravascular movement of fluidinto the pulmonary Pulmonary edema interstitium and alveoli. The four physiologic categories of edema include hydrostatic pressure edema, perme Chest radiograph ability edema with and without diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), and mixed edema where there is both an increase CT in hydrostatic pressure and membrane permeability.