NATURE-Learning-Resource.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Artist and the American Land

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1975 A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land Norman A. Geske Director at Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska- Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Geske, Norman A., "A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land" (1975). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 112. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME I is the book on which this exhibition is based: A Sense at Place The Artist and The American Land By Alan Gussow Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-154250 COVER: GUSSOW (DETAIL) "LOOSESTRIFE AND WINEBERRIES", 1965 Courtesy Washburn Galleries, Inc. New York a s~ns~ 0 ac~ THE ARTIST AND THE AMERICAN LAND VOLUME II [1 Lenders - Joslyn Art Museum ALLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM, OBERLIN COLLEGE, Oberlin, Ohio MUNSON-WILLIAMS-PROCTOR INSTITUTE, Utica, New York AMERICAN REPUBLIC INSURANCE COMPANY, Des Moines, Iowa MUSEUM OF ART, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, University Park AMON CARTER MUSEUM, Fort Worth MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON MR. TOM BARTEK, Omaha NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington, D.C. MR. THOMAS HART BENTON, Kansas City, Missouri NEBRASKA ART ASSOCIATION, Lincoln MR. AND MRS. EDMUND c. -

Download Our Exhibition Catalogue

CONTENTS Published to accompany the exhibition at Foreword 04 Two Temple Place, London Dodo, by Gillian Clarke 06 31st january – 27th april 2014 Exhibition curated by Nicholas Thomas Discoveries: Art, Science & Exploration, by Nicholas Thomas 08 and Martin Caiger-Smith, with Lydia Hamlett Published in 2014 by Two Temple Place Kettle’s Yard: 2 Temple Place, Art and Life 18 London wc2r 3bd Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: Copyright © Two Temple Place Encountering Objects, Encountering People 24 A catalogue record for this publication Museum of Classical Archaeology: is available from the British Library Physical Copies, Metaphysical Discoveries 30 isbn 978-0-9570628-3-2 Museum of Zoology: Designed and produced by NA Creative Discovering Diversity 36 www.na-creative.co.uk The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences: Cover Image: Detail of System According to the Holy Scriptures, Muggletonian print, Discovering the Earth 52 plate 7. Drawn by Isaac Frost. Printed in oil colours by George Baxter Engraved by Clubb & Son. Whipple Museum of the History of Science, The Fitzwilliam Museum: University of Cambridge. A Remarkable Repository 58 Inside Front/Back Cover: Detail of Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806), Komei bijin mitate The Polar Museum: Choshingura junimai tsuzuki (The Choshingura drama Exploration into Science 64 parodied by famous beauties: A set of twelve prints). The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. Whipple Museum of the History of Science: Thinking about Discoveries 70 Object List 78 Two Temple Place 84 Acknowledgements 86 Cambridge Museums Map 87 FOREWORD Over eight centuries, the University of Cambridge has been a which were vital to the formation of modern understandings powerhouse of learning, invention, exploration and discovery of nature and natural history. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Winnovative HTML to PDF Converter for .NET

ARCS homepage The Archival Spirit, February 2012 Newsletter of the Archivists of Religious Collections Section, Society of American Archivists Contents l Letter from the Chair: New ARCS Sparks! l From the Vice-Chair l Archives Workshop in Kenya l DePauw Celebrates 175th Anniversary l Lights, Cameras, Archives in Action: The Diocese of Olympia Archives Begins a Blog! l Christ Church Adds to its Online Database of Records l New Museum Exhibition Links American Artist’s Paintings and Young Pope’s Writings l Web Editor's Note From the Chair: New ARCS Sparks! By Terry Reilly Archivist, University of Calgary This is a creative moment in the world of the Archives of Religious Collections Section. The section has a lot of new energy. We are working ahead on several initiatives while continuing our important role of outreach to new religious archives and archivists. Do you know someone who is just starting out as a religious archivist or someone who is returning to the work after an absence or sabbatical? Encourage them to get in touch with ARCS. We want to incorporate as many new perspectives as we can. Are you associated with a regional religious archivists group? We will be excited to hear what is happening at your area meetings, exhibits or programming plans. Since our annual general meeting in Chicago we have held two steering committee conference calls. We know that regular communication is essential to effective planning. Also, based on your responses at the annual meeting, I have forwarded lists of your interests to members of the steering committee. -

Exibart.Onpaper 18 Sped

FREE Exibart.onpaper 18 Sped. in A.P. 45% art. 2. c. 20 A.P. in Sped. let. B - l. 662/96 Firenze Copia euro 0,0001 arte.architettura.design.musica.moda.filosofia.hitech.teatro.videoclip.editoria.cinema.gallerie.danza.trend.mercato.politica.vip.musei.gossip eventi d'arte in italia | anno terzo | novembre - dicembre 2004 www.exibart.com Un numero così non l'avete mai visto. Ad iniziare dalla cover, come sempre d'autore: questa volta -il tratto urban è inconfondibile- la firmano Botto e Bruno. All'interno quattro chiac- chiere con il fotografo più hot del momento, Terry Richardson. Lo abbiamo incontrato a Bologna, per la presentazione del suo libro. Diario per immagini tenero, scandaloso, sexy, impre- vedibile… ovviamente limited edition. Ve ne diamo un assaggio pepatissimo in una pagina di sole foto. Quelle che nessun'altra rivista (in Italia) ha osato pubblicare. Ricordiamo il filo- sofo Jacques Derida, recentemente scomparso. Senza retorica, due contributi: uno pro ed uno contro. Un'altra pagina la dedichiamo a Donald Judd, papà del Minimal, di cui ricorrono dieci anni dalla morte (anche qui ci sa tanto di essere stati gli unici a ricordarcelo). E a Cristopher Reeve, al mito di Superman e all'immortalità formato celluloide. E ancora. Nuovi spazi che aprono i battenti, overview dalla Biennale di Architettura ed un incontro a tu per tu con Miss Graffiti -al secolo Miss Van- giovane artista di Tolosa che ha firmato la nuova col- lezione della griffe Fornarina. E poi le mostre da non perdere in Italia e all'estero, un giovane designer da tener d'occhio, libri, teatro, parliamo pure di Brian Wilson deus ex machina dei beach Boys, che ha dato alla luce -meglio tardi che mai!- un progetto durato trent'anni. -

Eleonora Caracciolo Di Torchiarolo 00 REPORT LAUREL HOLLOMAN in Senso Orario/ Clockwise Let Me Fall, 2012

di/by Eleonora Caracciolo di Torchiarolo 00 REPORT LAUREL HOLLOMAN In senso orario/ clockwise Let Me Fall, 2012 Between Two Seas, 2012 Memory Loss, 2012 Red Rain, 2012 Nella Pagina a fianco / On the other page Gravity Always Wins, 2012 VENEZIA • PERSONALE Armoniosa energia DI LAUrel Il filo rosso che lega le opere mezzo della sua vita cambia Falling” in corso all’Ateneo nello stesso tempo cerca HolloMan e la vita di Laurel Holloman è decisamente rotta e passa da Veneto di Venezia fino al 29 l’accordo che risuona sicuro, la scelta di muoversi sempre un settore artistico proiettato, settembre, la Holloman si la bellezza che nasce, molto ALL’ATENEO nella direzione dell’unione, della per così dire, verso l’esterno propone di esplorare i temi del semplicemente, dal suscitare coesione e dell’armonia fra e l’esteriorità a uno diretto rinnovamento e della rinascita emozioni”. VENETO fattori difformi e lontani. all’intimità e alla spiritualità di spirituale attraverso la coesione È tutto qui e ora nelle grandi tele Prima di tutto un dato ciascuno. – eccoci di nuovo – tra natura, di Laurel Holloman: la luce e le / OVERVIEW PANORAMA biografico, che sempre dà Il suo fare arte prende immagini elementari e vita tenebre, il dolore e la gioia, la importanti indicazioni sul modo chiaramente le mosse umana, dove per “immagini materia e lo spirito, in cui, grazie di lavorare di un artista: la dall’espressionismo astratto, elementari” l’artista intende le alle monumentali dimensioni, Holloman è celebre negli Stati movimento che forse più di raffigurazioni di acqua, fuoco, l’osservatore viene risucchiato, Uniti per essere attrice di serie altri, coerenti e omogenei aria e terra, e a “vita umana” avvolto, abbracciato, in televisive di successo. -

Paper Barassi

UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS IN SCOTLAND CONFERENCE 2004 The collection as a work of art: Jim Ede and Kettle's Yard Sebastiano Barassi Curator of Collections Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge [email protected] The significance of a collection depends upon a wide range of value judgements. And indeed ‘significance’ itself is a multifaceted term, which can refer to the mere quality of having a meaning as well as imply a hierarchical determination. In this paper I would like to propose a definition of the significance of a collection based upon ideas developed for art criticism and exemplified by the history of the creation of Kettle’s Yard. *** In his 1914 book Art , Bloomsbury writer and critic Clive Bell thus outlined the notion of ‘significant form’: “What quality is shared by all objects that provoke our aesthetic emotions? In each, lines and colours combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions. These relations and combinations I call ‘Significant Form’; and ‘Significant Form’ is the one quality common to all works of visual art.” Bell’s definition became the founding principle of Formalism, a doctrine that has since grown out of fashion among art historians and museum professionals. However, I would like to suggest that the notion of ‘significance’ as the ability to stir emotions, can usefully be applied to collections (not only art collections) to help define their role in today’s society. I hope that the story of the creation of Kettle’s Yard will provide a helpful example. Kettle’s Yard was created in 1956 by Harold Stanley Ede, who was known to his friends as Jim. -

Feb 2 7 2004 Libraries Rotch

Architecture Theory 1960-1980. Emergence of a Computational Perspective by Altino Joso Magalhses Rocha Licenciatura in Architecture FAUTL, Lisbon (1992) M.Sc. in Advanced Architectural Design The Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation Columbia University, New York. USA (1995) Submitted to the Department of Architecture, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: Design and Computation at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OF TECHNOLOGY February 2004 FEB 2 7 2004 @2004 Altino Joso Magalhaes Rocha All rights reserved LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author......... Department of Architecture January 9, 2004 Ce rtifie d by ........................................ .... .... ..... ... William J. Mitchell Professor of Architecture ana Media Arts and Sciences Thesis Supervisor 0% A A Accepted by................................... .Stanford Anderson Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Head, Department of Architecture ROTCH Doctoral Committee William J. Mitchell Professor of Architecture and Media Arts and Sciences George Stiny Professor of Design and Computation Michael Hays Eliot Noyes Professor of Architectural Theory at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design Architecture Theory 1960-1980. Emergence of a Computational Perspective by Altino Joao de Magalhaes Rocha Submitted to the Department of Architecture on January 9, 2004 in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: Design and Computation Abstract This thesis attempts to clarify the need for an appreciation of architecture theory within a computational architectural domain. It reveals and reflects upon some of the cultural, historical and technological contexts that influenced the emergence of a computational practice in architecture. -

“Uproar!”: the Early Years of the London Group, 1913–28 Sarah Macdougall

“Uproar!”: The early years of The London Group, 1913–28 Sarah MacDougall From its explosive arrival on the British art scene in 1913 as a radical alternative to the art establishment, the early history of The London Group was one of noisy dissent. Its controversial early years reflect the upheavals associated with the introduction of British modernism and the experimental work of many of its early members. Although its first two exhibitions have been seen with hindsight as ‘triumphs of collective action’,1 ironically, the Group’s very success in bringing together such disparate artistic factions as the English ‘Cubists’ and the Camden Town painters only underlined the fragility of their union – a union that was further threatened, even before the end of the first exhibition, by the early death of Camden Town Group President, Spencer Gore. Roger Fry observed at The London Group’s formation how ‘almost all artist groups’, were, ‘like the protozoa […] fissiparous and breed by division. They show their vitality by the frequency with which they split up’. While predicting it would last only two or three years, he also acknowledged how the Group had come ‘together for the needs of life of two quite separate organisms, which give each other mutual support in an unkindly world’.2 In its first five decades this mutual support was, in truth, short-lived, as ‘Uproar’ raged on many fronts both inside and outside the Group. These fronts included the hostile press reception of the ultra-modernists; the rivalry between the Group and contemporary artists’ -

The Market & the Muse

The Market & The Muse: 18 19 IF AN ARTIST PAINTS IN MONASTIC SECLUSION, IS IT ART? BY CHRISTOPHER REARDON IF AN ARTIST PAINTS IN MONASTIC SECLUSION, IS IT ART? CHRISTOPHER REARDON THE MARKET & THE MUSE: Congdon, who was born the night the Titanic sank, believed that he, IF AN ARTIST PAINTS IN MONASTIC SECLUSION, IS IT ART? too, was destined to go to an early grave. Certainly in the 1950s he kept on a collision course. In a letter from Guatemala City in 1957, he told his cousin, the poet Isabella Gardner, a descendant of the Boston collector Isabella Stewart Gardner, of the hazardous nature of his creative process. “In order to have a pure birth,” he wrote, using a metaphor he often applied to his viscer- al style of action painting, “I must go through scenes little short of suicide and not a bit short of madness and destruction.” No model of stability herself, Gardner saw his paintings (and her own writing) as the flowering of an oth- erwise noxious ancestral weed she called, in a poem so titled, “The Panic Vine.” Ultimately, though, Congdon found a way to untangle himself both from the manic tendencies that were said to run through his family and from the self-annihilation that came to characterize the New York School. In August 1959, he went to Assisi, Italy, and converted to Roman Catholicism. n the outskirts of Milan, just By then, some of his spirited cityscapes of New York and Venice, often 20 seven miles from the dazzlingO fashion district where Gianni Versace and rendered in thick strokes of black and gold, had already entered the perma- 21 Miucci Prada launched their careers, a two-hundred-year-old manor house nent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern stands among several acres of barley, corn, and soy. -

History of Freemasonry in New Jersey

History of Freemasonry in New Jersey Commemorating the Two Hundredth Anniversary Of the Organization of the Grand Lodge of THE MOST ANCIENT AND HONORABLE SOCIETY OF FREE AND ACCEPTED MASONS for the State of New Jersey 1787-1987 Written And Prepared By The History Committee R.W. Edward Y. Smith, Jr., Grand Historian, Covenant No. 161 R.W. Earl G. Gieser, Past Junior Grand Deacon, Wilkins-Eureka No. 39 W. George J. Goss, Solomon's No. 46 R.W. Frank Z. Kovach, Past Grand Chaplain, Keystone No. 153 R.W. R. Stanford Lanterman, Past District Deputy Grand Master, Cincinnati No. 3 First Edition Index Contents Chapter Title Page I Antecedents 1682-1786 ···························· 1 II The Foundation Of The Grand Lodge 1786-1790 . .. ...... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... .. ... 5 ITI The Formative Years 1791-1825 .............. 9 IV A Time Of Trouble 1826-1842 ................ 15 V A Renewal Of Purpose 1843-1866 ........... 19 VI The Years Of Stability 1867-1900 ........... 23 VII The Years Of Growth 1901-1930 . 29 VITI Depression And Resurgence 1931-1957 .... 35 IX The Present State Of Affairs 1958-1986 .. 39 Appendix Lodges Warranted In New Jersey Lodges Warranted Prior To 1786 . 46 Lodges Warranted 1787 To 1842 . 46 Lodges Warranted Following 1842 . 50 Appendix Famous New Jersey Freemasons . 67 Appendix Elective Officers Of The Grand Lodge Since Organization . 98 Lieut. Colonel David Brearley, Jr. circa 1776-1779 The Hon. David Brearley, Jr. circa 1786-1790 The First R. W Grand Master-1786-1790 Grand Lodge, F. & A. M. of New Jersey Whitehall Tavern, New Brunswick, N.J. circa 1786 l. #-~-~ .. ~- Whitehall Tavern, New Brunswick, N.J. -

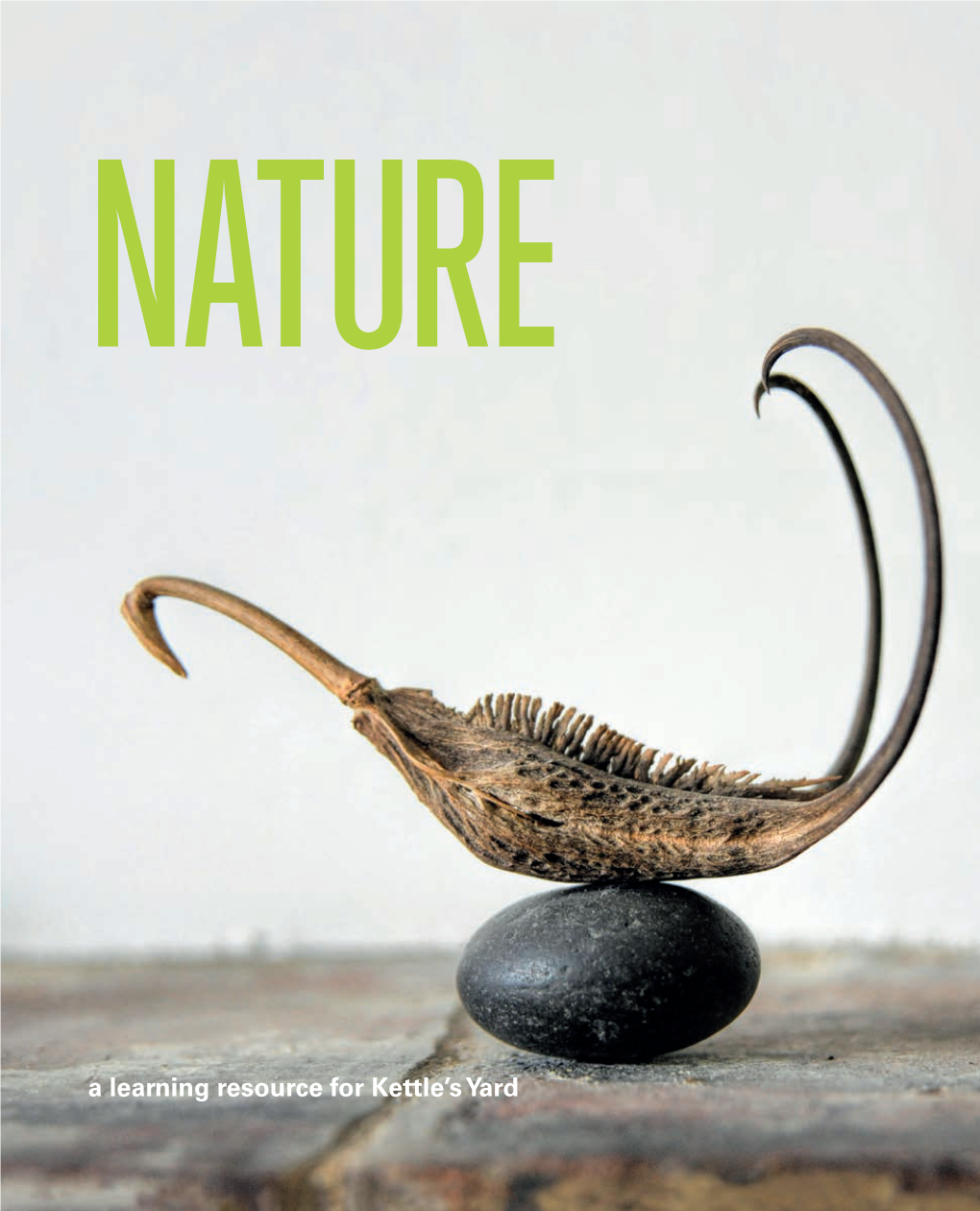

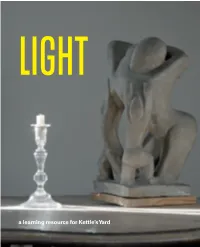

Learning About Light, Nature and Space at Kettle's

LIGHT a learning resource for Kettle’s Yard LIGHT a learning resource for Kettle’s Yard This learning resource is designed to help teachers and educators engage their students with the house and collection at Kettle’s Yard. Light is the !rst of three publications which focus on one of the key themes of the house – Light, Nature and Space. Each resource includes: detailed information on selected artworks and objects artists’ biographies examples of contemporary art discussion-starters and activities You will !nd useful information for pre-visit planning, supporting groups during visits and leading progression activities back in the classroom. Group leaders can use this information in a modular way – content from the sections on artworks and objects can be ‘mixed and matched’ with the simple drawing and writing activities to create a session. This publication was written by the Kettle’s Yard Learning Team with contributions from: Sarah Campbell, Bridget Cusack, Rosie O’Donovan, Sophie Smiley and Lucy Wheeler. With many thanks to teachers Lizzy McCaughan, Jonathan Stanley, Nicola Powys, Janet King and students from Homerton Initial Teacher Training course for their thoughtful ideas and feedback. CONTENTS Introduction What is Kettle’s Yard? 5 Light at Kettle’s Yard 7 Artworks and Objects in the House Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Wrestler s 9 David Peace, Canst thou bind the Cluster of the Pleiades 13 Dancer Room 17 Winifred Nicholson, Cyclamen and Primula 21 Gregorio Vardanega, Disc 25 Bryan Pearce, St Ives Harbour 29 Kenneth Martin, Screw mobile 33 Venetian Mirror 35 Constantin Brancusi, Prometheus 39 Contemporary works exhibited at Kettle’s Yard Lorna Macintyre, Nocturne 45 Tim Head, Sweet Bird 46 Edmund de Waal, Tenebrae No.2 49 Contemporary Artists’ Biographies 51 More Ideas and Information Talking about art 55 Drawing activities 57 Word and image 59 How to book a group visit to Kettle’s Yard 61 Online resources 62 2 WHAT IS KETTLE’S YARD? Kettle’s Yard was the home of Jim and Helen Ede from 1957-1973.