Paper Barassi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Our Exhibition Catalogue

CONTENTS Published to accompany the exhibition at Foreword 04 Two Temple Place, London Dodo, by Gillian Clarke 06 31st january – 27th april 2014 Exhibition curated by Nicholas Thomas Discoveries: Art, Science & Exploration, by Nicholas Thomas 08 and Martin Caiger-Smith, with Lydia Hamlett Published in 2014 by Two Temple Place Kettle’s Yard: 2 Temple Place, Art and Life 18 London wc2r 3bd Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: Copyright © Two Temple Place Encountering Objects, Encountering People 24 A catalogue record for this publication Museum of Classical Archaeology: is available from the British Library Physical Copies, Metaphysical Discoveries 30 isbn 978-0-9570628-3-2 Museum of Zoology: Designed and produced by NA Creative Discovering Diversity 36 www.na-creative.co.uk The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences: Cover Image: Detail of System According to the Holy Scriptures, Muggletonian print, Discovering the Earth 52 plate 7. Drawn by Isaac Frost. Printed in oil colours by George Baxter Engraved by Clubb & Son. Whipple Museum of the History of Science, The Fitzwilliam Museum: University of Cambridge. A Remarkable Repository 58 Inside Front/Back Cover: Detail of Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806), Komei bijin mitate The Polar Museum: Choshingura junimai tsuzuki (The Choshingura drama Exploration into Science 64 parodied by famous beauties: A set of twelve prints). The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. Whipple Museum of the History of Science: Thinking about Discoveries 70 Object List 78 Two Temple Place 84 Acknowledgements 86 Cambridge Museums Map 87 FOREWORD Over eight centuries, the University of Cambridge has been a which were vital to the formation of modern understandings powerhouse of learning, invention, exploration and discovery of nature and natural history. -

Art and Life

Resource Notes – for teachers and group leaders Art and Life is an exhibition of paintings and pottery produced between 1920 and 1931 by artists Ben Nicholson, Winifred Nicholson, Christopher Wood, Alfred Wallis and William Staite Murray. All the artists knew each other personally, exhibited or worked together and shared similar values in terms of making art. Jim Ede, creator of Kettle's Yard, was a friend and a supporter of these artists, who played a central role in shaping his taste and approach to life. Their artwork makes up a key part of the Kettle’s Yard permanent collection. Art and Life shows British painting during a period of change, when representational painting was replaced by a more gestural, ‘felt’ abstraction. Painting was no longer about producing a technically accomplished representation of the real world, but about expressing 'lived' experience, through colour, form and movement. The process of making art came to be about the spiritual as well as the visual; about vitality, Winifred Nicholson, Autumn Flowers on a experience and intuition and re-connecting the Mantlepiece,1932. Oil on wood panel, 76 x person with life through art. 60cm. Private Collection © Trustees of Winifred Nicholson The Artists Winifred and Ben Nicholson grew up in an environment that gave them access to artists, artworks and intellectual society. Although working closely together, Winifred and Ben's paintings were quite different. Winifred's emphasis was strongly on colour and light whereas Ben focused more on line, muted colours and abstract, simple forms. Christopher Wood met the Nicholsons in 1926 and became a close friend, living with them for periods of time in Cumbria and St Ives, Cornwall. -

Welcome to the Laing Art Gallery and Articulation

WELCOME TO THE LAING ART GALLERY AND ARTICULATION The Laing Art Gallery sits in the heart of Newcastle City Centre and opened its doors in 1904 thanks to the local merchant Alexander Laing who gifted the gallery to the people of Newcastle. Unusually, when the Laing Art Gallery first opened, it didn’t have a collection! Laing was confident that local people would support the Gallery and donate art. In the early days the Gallery benefitted from a number of important gifts and bequests from prominent industrialists, public figures, art collectors, and artists. National galleries and museums continued to lend works, and, three years after opening its doors, the Laing began to acquire art. In 1907, the Gallery’s first give paintings were purchased. Over the last 100 years, the Laing’s curators have continued to build the collection, and it is now a Designated Collection, recognised as nationally important by Arts Council England. The Laing Art Gallery’s exceptional collection focuses on but is not limited to British oil paintings, watercolours, ceramics, and silver and glassware, as well as modern and contemporary pieces of art. We also run temporary exhibition programmes which change every three months. WELCOME TO THE LAING ART GALLERY! Here is your chosen artwork: 1933 (design) by Ben Nicholson Key Information: By Ben Nicholson Produced in 1933 Medium: Oil and pencil on panel Dimensions: (unknown) Location: Laing Art Gallery Currently on display in Gallery D PAINTING SUMMARY 1933 (design) is part of a series of works produced by Nicholson in the year of its title. The principle motif of these paintings is the female profile. -

Joys of the East TEFAF Online Running from November 1-4 with Preview Days on October 30 and 31

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp ISSUE 2463 | antiquestradegazette.com | 17 October 2020 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 koopman rare art antiques trade KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY [email protected] +44 (0)20 7242 7624 www.koopman.art Main picture: Jagat Singh II (1734-51) enjoying TEFAF moves a dance performance (detail) painted in Udaipur, c.1740. From Francesca Galloway. to summer Below: a 19th century Qajar gold and silver slot for 2021 inlaid steel vase. From Oliver Forge and Brendan Lynch. The TEFAF Maastricht fair has been delayed to May 31-June 6, 2021. It is usually held in March but because of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic the scheduled dates have been moved, with the preview now to be held on May 29-30. The decision to delay was taken by the executive committee of The European Fine Art Foundation (TEFAF). Chairman Hidde van Seggelen said: “It is our hope that by pushing the dates of TEFAF Maastricht to later in the spring, we make physical attendance possible, safe, and comfortable for our exhibitors and guests.” Meanwhile, TEFAF has launched a digital marketplace for dealers with the first Joys of the East TEFAF Online running from November 1-4 with preview days on October 30 and 31. Two-part Asian Art in London begins with Indian and Islamic art auctions and dealer exhibitions Aston’s premises go This year’s ‘Islamic Week’, running from 29-November 7. -

Feb 2 7 2004 Libraries Rotch

Architecture Theory 1960-1980. Emergence of a Computational Perspective by Altino Joso Magalhses Rocha Licenciatura in Architecture FAUTL, Lisbon (1992) M.Sc. in Advanced Architectural Design The Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation Columbia University, New York. USA (1995) Submitted to the Department of Architecture, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: Design and Computation at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OF TECHNOLOGY February 2004 FEB 2 7 2004 @2004 Altino Joso Magalhaes Rocha All rights reserved LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author......... Department of Architecture January 9, 2004 Ce rtifie d by ........................................ .... .... ..... ... William J. Mitchell Professor of Architecture ana Media Arts and Sciences Thesis Supervisor 0% A A Accepted by................................... .Stanford Anderson Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Head, Department of Architecture ROTCH Doctoral Committee William J. Mitchell Professor of Architecture and Media Arts and Sciences George Stiny Professor of Design and Computation Michael Hays Eliot Noyes Professor of Architectural Theory at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design Architecture Theory 1960-1980. Emergence of a Computational Perspective by Altino Joao de Magalhaes Rocha Submitted to the Department of Architecture on January 9, 2004 in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: Design and Computation Abstract This thesis attempts to clarify the need for an appreciation of architecture theory within a computational architectural domain. It reveals and reflects upon some of the cultural, historical and technological contexts that influenced the emergence of a computational practice in architecture. -

BEN NICHOLSON / GERARDO RUEDA: Confluencias BEN NICHOLSON / GERARDO RUEDA: CONFLUENCIAS

BEN NICHOLSON / GERARDO RUEDA: CONFLUENCIAS BEN NICHOLSON / GERARDO RUEDA: CONFLUENCIAS 2 BEN NICHOLSON / GERARDO RUEDA: CONFLUENCIAS Del 19 de noviembre de 2013 al 10 de enero de 2014 GALERIA LEANDRO NAVARRO C/ AMOR DE DIOS, Nº1 28014 MADRID Horario: de Lunes a Viernes de 10 a 14h. y de 17 a 20h. Sábado previa cita. Tel.: 91 429 89 55 Fax: 91 429 91 55 e-mail: [email protected] www.leandro-navarro.com NICHOLSON Y RUEDA. FRENTE AL MAR. confluencia en un asunto capital, lo que Herbert Read citaba como “pureza de 6 7 Dos artistas jóvenes se hallan frente al mar, es el mismo agua de Normandía: Nicholson está en estilo” , la búsqueda de eso que Nicholson llamaba la “clear light” . Así, ambos Dieppe1 y Rueda en Deauville. Ambos miran, cuando es calmo el océano, los barcos de vela cruzar el hori- artistas partirán no tanto del cubismo que, como no podía ser menos en uno zonte y analizan las curiosas formas, triángulos y verticales, líneas y planos que estos componen sobre la de los momentos cruciales del arte del siglo veinte, es ciertamente revisitado planicie del agua, en el azul del cielo de verano. El artista inglés mira ese mar y que se aprecia ocasionalmente en sus pinturas, pero sus miradas no esqui- en los años treinta2, nuestro Rueda mediados los cincuenta3. Aquél, poético van la admiración por la tradición clásica, sin complejo, y ambos citarán a los pintores primitivos para desde ahí viajar después defensor de las emociones, en tanto este, también proustiano, escribe: “Una Gerardo Rueda. -

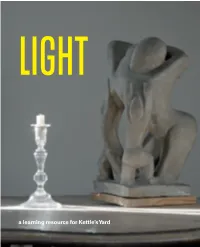

Learning About Light, Nature and Space at Kettle's

LIGHT a learning resource for Kettle’s Yard LIGHT a learning resource for Kettle’s Yard This learning resource is designed to help teachers and educators engage their students with the house and collection at Kettle’s Yard. Light is the !rst of three publications which focus on one of the key themes of the house – Light, Nature and Space. Each resource includes: detailed information on selected artworks and objects artists’ biographies examples of contemporary art discussion-starters and activities You will !nd useful information for pre-visit planning, supporting groups during visits and leading progression activities back in the classroom. Group leaders can use this information in a modular way – content from the sections on artworks and objects can be ‘mixed and matched’ with the simple drawing and writing activities to create a session. This publication was written by the Kettle’s Yard Learning Team with contributions from: Sarah Campbell, Bridget Cusack, Rosie O’Donovan, Sophie Smiley and Lucy Wheeler. With many thanks to teachers Lizzy McCaughan, Jonathan Stanley, Nicola Powys, Janet King and students from Homerton Initial Teacher Training course for their thoughtful ideas and feedback. CONTENTS Introduction What is Kettle’s Yard? 5 Light at Kettle’s Yard 7 Artworks and Objects in the House Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Wrestler s 9 David Peace, Canst thou bind the Cluster of the Pleiades 13 Dancer Room 17 Winifred Nicholson, Cyclamen and Primula 21 Gregorio Vardanega, Disc 25 Bryan Pearce, St Ives Harbour 29 Kenneth Martin, Screw mobile 33 Venetian Mirror 35 Constantin Brancusi, Prometheus 39 Contemporary works exhibited at Kettle’s Yard Lorna Macintyre, Nocturne 45 Tim Head, Sweet Bird 46 Edmund de Waal, Tenebrae No.2 49 Contemporary Artists’ Biographies 51 More Ideas and Information Talking about art 55 Drawing activities 57 Word and image 59 How to book a group visit to Kettle’s Yard 61 Online resources 62 2 WHAT IS KETTLE’S YARD? Kettle’s Yard was the home of Jim and Helen Ede from 1957-1973. -

Contemporary Art Society Report 1934-1935

CONTEMPORARY ART SOCIETY REPORT 1934-1935 THE CONTEMPORARY ART SOCIETY For the Acquisition of Works of Modern Art for Loan or Gift to Public Galleries President: LORD HOWARD DE WALDEN Treasttrer and Chairman: SIR C. KENDALL-BUTLER, K.B.E. Bourton House, Shrivenham Honorary Secretary : LORD IVOR SPENCER-CHURCHILL 4 John Street, Mayfair, W. 1 Committee : SIR C. KENDALL-BUTLER, K.B.E. (Chairman) Lord Balniel, M.P. Edward Marsh, C.B., C.M.G., Muirhead Bone C.V.O. Samuel Courtauld Ernest Marsh Sir A. M. Daniel, K.B.E. The Hon. Jasper Ridley Campbell Dodgson, C.B.E. Sir Michael Sadler, K.C.S.I., C.B. A. M. Hind, O.B.E. Earl of Sandwich St. John Hutchinson, K.C. Montague Shearman J. Maynard Keynes, C.B. Lord Ivor Spencer-Churchill J. B. Manson C. L. Stocks, C.B. Assiffant Secretary: Mr. H. S. EDE I THF. BLUE BARGE, WEYMOUTH Richard Eurich REPORT THIS Report of the activities of the Society during the past two years is circulated in the hope that it may encourage members to talk about the Society, and make it widely known amongst their friends. In these days of economy, when people hesitate to spend much on pictures, it should at least be possible for them, if they are interested in art and artists, to spend a guinea on becoming a member of the Society. By so doing, they would be helping to acquire works of art to be given eventually to the Nation's public galleries, and at the same time they would be assisting artists. -

The Interwar Years,1930S

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • My sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN • The Aesthetic Movement, 1860-1880 • Late Victorians, 1880-1900 • The Edwardians, 1890-1910 • The Great War and After, 1910-1930 • The Interwar Years, 1930s • World War II and After, 1940-1960 • Pop Art & Beyond, 1960-1980 • Postmodern Art, 1980-2000 • The Turner Prize • Summary West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

British Art Studies May 2019 British Art Studies Issue 12, Published 31 May 2019

British Art Studies May 2019 British Art Studies Issue 12, published 31 May 2019 Cover image: Margaret Mellis, Red Flower (detail), 1958, oil on board, 39.4 x 39.1 cm. Collection of Museums Sheffield (VIS.4951).. Digital image courtesy of the estate of Margaret Mellis. Photo courtesy of Museums Sheffied (All rightseserved). r PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Cumbrian Cosmopolitanisms: Li Yuan-chia and Friends, Hammad Nasar Cumbrian Cosmopolitanisms: Li Yuan-chia and Friends Hammad Nasar Abstract The LYC Museum & Art Gallery (the LYC) in the Cumbrian village of Banks (astride Hadrian’s Wall) was the single-minded effort of artist Li Yuan-chia (1929–1994). -

Artlyst Recommendends Artlyst

Artlyst Out of London museums reopen for summer season 2021 – Artlyst Recommendends 5 May 2021 Out of London Museums Reopen for Summer Season 2021 – Artlyst Recommends 5 May 2021 / Art Categories Features / Art Tags Out of London Exhibitions 2021, Summer 2021 Image: photo Sara Faith ©Artlyst 2021 As Museums and Galleries plan their reopenings after the current Covid restrictions and the public plan their Summer staycations, Artlyst has put together a selection of exhibitions throughout the country to get you through the season. John Nash: Towner Eastbourne John Nash: The Landscape of Love and Solace Towner Eastbourne, Eastbourne 18 May – 26 September 2021 Towner Eastbourne presents the most comprehensive major exhibition of work in over 50 years by John Nash, one of the most versatile and prolific artists of the 20th century. In a career spanning more than seven decades, Nash produced work across a range of mediums, from iconic oil paintings, now housed in some of Britain’s most important collections, to accomplished wood engravings, line-drawings, lithographs and watercolours. William Roberts, Seaside Modern, Hastings Contemporary Seaside Modern: Art and Life on the Beach. Hastings Contemporary, 27 May 2021 – 26 September 2021 Featuring paintings, photographs, posters and more, dating from 1920 to 1970, Seaside Modern will explore the relationship between artists and the seaside. While some artists, such as LS Lowry and William Roberts, depicted the people who thronged the beaches, others, like Paul Nash and Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, explored the coastal landscape itself. Poster designers enticed holidaymakers to the coast with images of glamorous young people in stylish swimwear, as the seaside became both popular and fashionable. -

NATURE-Learning-Resource.Pdf

NATURE a learning resource for Kettle’s Yard NATURE a learning resource for Kettle’s Yard This learning resource is designed to help teachers and educators engage and inspire their students through the house and collection at Kettle’s Yard. Nature is the second of three publications which focus on key themes of the house – Light, Nature and Space. Inside, you will find: information on artworks and objects artists’ biographies examples of contemporary responses to nature ideas and information for visiting with groups Content from different sections on artworks and objects can be mixed and matched with the simple drawing and writing activities to create the right session for your group. 1 CONTENTS What is Kettle’s Yard? 4 Nature at Kettle’s Yard 7 Artwork and Objects in the House Ben Nicholson 9 Pebbles 14 Ian Hamilton Finlay 16 Henry Moore 18 William Congdon 22 The Bridge 25 William Staite Murray 28 Elisabeth Vellacott 31 Christopher Wood 32 Henri Gaudier-Brzeska 36 Contemporary Responses to Nature Katie Paterson 41 Andy Holden 44 Anthea Hamilton 47 More Ideas and Information Talking About Art 53 Drawing Activities 55 Word and Image 57 How to book a visit to Kettle’s Yard 59 Online Resources 61 2 3 When Jim was working at the Tate Gallery, London, in the 1920s and 1930s, he befriended a young generation of artists including Ben and Winifred Nicholson, Christopher Wood and David Jones. Jim supported his artist friends by purchasing artworks early in their careers. Their paintings, prints and drawings formed the basis of the Kettle’s Yard collection.