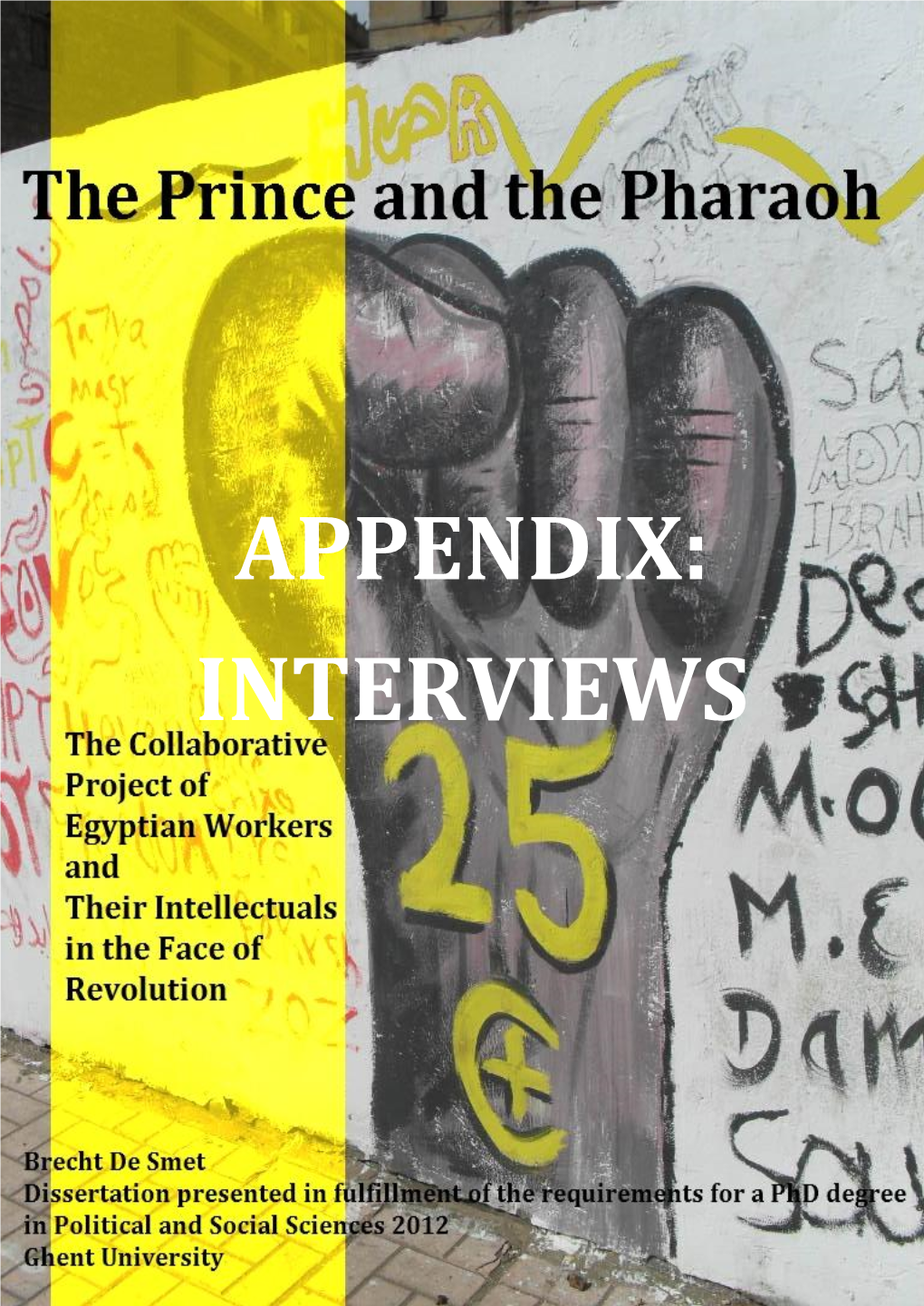

Appendix: Interviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Opposition in an Authoritarian Context a Historical Reconstruction of the Moroccan Left from Independence to the Present Day

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Lingue, economie e istituzioni dell’Asia e dell’Africa mediterranea Tesi di Laurea Political opposition in an authoritarian context A historical reconstruction of the Moroccan left from independence to the present day Relatrice Ch.ma Prof.ssa Barbara de Poli Correlatrice Ch.ma Prof.ssa Maria Cristina Paciello Laureando Daniele Paolini Matricola 874978 Anno Accademico 2019/2020 وطن المرء ليس مكان وﻻدته ولكنه المكان الذي تنتهي فيه كل محاوﻻته للهروب نجيب محفوظ Home is not where you were born; home is where all your attempts to escape cease. Naguib Mahfouz TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 ................................................................................................................................................... المقدمة INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 5 METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH ................................................................................................ 10 CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................................................ 14 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 14 2. THE FRENCH PROTECTORATE ........................................................................................... 14 3. THE FRENCH LEFTIST IN MOROCCO ................................................................................ 18 4. POLITICAL -

Egyptian Political Parties and

(Doha Institute) www.dohainstitute.org Commentary Egyptian Political Parties and Parliamentary Elections 2011/2012 Ahmad Abed Rabbo Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies Commentary Doha, December- 2011 Commentary Series Copyrights reserved for Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies © 2011 Contents EGYPTIAN POLITICAL PARTIES ........................................ AND PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 2011/2012 .................. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF THE ELECTIONS ...................................................... 1 COMPETING PARTIES AND COALITIONS ................................................................ 2 PARTY ALLIANCES .................................................................................................. 3 NON-ALLIED PARTIES ............................................................................................. 4 PARTIES THAT EMANATED FROM THE DISSOLVED NATIONAL PARTY .................. 4 THE MAIN ELECTION CHALLENGES FACING THE PARTIES .................................. 5 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................... 5 Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies Egyptian Political Parties Introduction The first phase of elections for the People’s Assembly and Shura Council in the Arab Republic of Egypt was launched on November 28, 2011, and the last phase will end on March 11, 2012. Initial results are expected to produce -

From Revolution to Coalition – Radical Left Parties in Europe

e P uro e t Parties in t Parties F e l evolution to Coalition – r al C Birgit Daiber, Cornelia Hildebrandt, Anna Striethorst (Ed.) adi r From From revolution to Coalition – radiCal leFt Parties in euroPe 2 Manuskripte neue Folge 2 r osa luxemburg stiFtung Birgit Daiber, Cornelia Hildebrandt, Anna Striethorst (Ed.) From Revolution to Coalition – Radical Left Parties in Europe Birgit Daiber, Cornelia Hildebrandt, Anna Striethorst (Ed.) From revolution to Coalition – radiCal leFt Parties in euroPe Country studies of 2010 updated through 2011 Phil Hill (Translation) Mark Khan, Eoghan Mc Mahon (Editing) IMPRINT MANUSKRIPTE is published by Rosa-Luxemburg-Foundation ISSN 2194-864X Franz-Mehring-Platz 1 · 10243 Berlin, Germany Phone +49 30 44310-130 · Fax -122 · www.rosalux.de Editorial deadline: June 2012 Layout/typesetting/print: MediaService GmbH Druck und Kommunikation, Berlin 2012 Printed on Circleoffset Premium White, 100 % Recycling Content Editor’s Preface 7 Inger V. Johansen: The Left and Radical Left in Denmark 10 Anna Kontula/Tomi Kuhanen: Rebuilding the Left Alliance – Hoping for a New Beginning 26 Auður Lilja Erlingsdóttir: The Left in Iceland 41 Dag Seierstad: The Left In Norway: Politics in a centre-left government 50 Barbara Steiner: «Communists we are no longer, Social Democrats we can never be the Swedish Left Party» 65 Thomas Kachel: The British Left At The End Of The New Labour Era – An Electoral Analysis 78 Cornelia Hildebrandt: The Left Party in Germany 93 Stéphane Sahuc: Left Parties in France 114 Sascha Wagener: The Left -

Comparing Two Regime Crises in Syria: Regional Actors and Russian Involvement

Comparing Two Regime Crises in Syria: Regional Actors and Russian Involvement SULTAN ALTAMIMI (21010106) BA, Edith Cowan University, 2009 MA, Curtin University, 2012 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social Sciences (Political Science and International Relations) 2017 ii Candidate’s Declaration Having completed my course of study and research towards the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, I hereby submit my thesis for examination in accordance with the regulations and declare: The thesis is my own composition, all sources have been acknowledged and my contribution is clearly identified in the thesis. This thesis does not breach any ethical rules with regard to the conduct of the research. The thesis has been substantially completed during the course of enrolment in this degree at UWA and has not previously been accepted for a degree at this or another institution. Signature: Date: 13/07/2018 iii iv Abstract This thesis considers the causes of Middle Eastern and Russian involvement in the two Syrian crises of 1982 and since 2011 from a geopolitical perspective. Middle Eastern and Russian involvement in the two Syrian crises was the result of the absence of a regional regulatory system that is capable of considering the geopolitical interests of regional actors and resolving, or even preventing, interstate conflicts without resorting to violence. The absence of a regulatory system in the Middle East is due to the fact that the region is not highly developed as a whole, according to the stage of maturity of Saul B. Cohen’s World Geopolitical System theory, which has been applied in this study. -

Westminsterresearch

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Islamists and democracy in Sudan: the role of Hasan Turabi, 1989-2001 Suhair Ahmed Salah Mohammed School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Languages This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2012. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] ISLAMISTS AND DEMOCRACY IN SUDAN: THE ROLE OF HASAN TURABI 1989-2001 S. A. S. Mohammed PhD 2012 ISLAMISTS AND DEMOCRACY IN SUDAN: THE ROLE OF HASAN TURABI 1989-2001 SUHAIR AHMED SALAH MOHAMMED A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2012 Abstract This research assesses the experiment of the Islamic movement in Sudan following the 1989 coup. The main question that needs to be answered with regard to Turabi and the Islamists in Sudan is the gap between theory and practice.