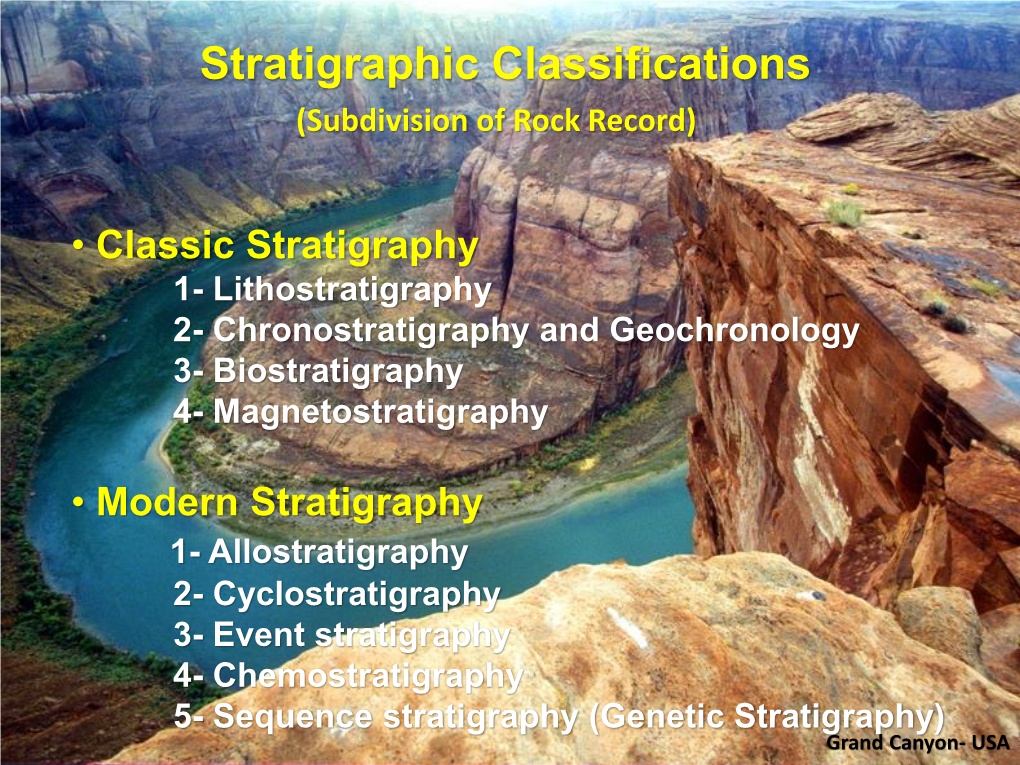

Stratigraphic Classifications (Subdivision of Rock Record)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do Gssps Render Dual Time-Rock/Time Classification and Nomenclature Redundant?

Do GSSPs render dual time-rock/time classification and nomenclature redundant? Ismael Ferrusquía-Villafranca1 Robert M. Easton2 and Donald E. Owen3 1Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, México, DF, MEX, 45100, e-mail: [email protected] 2Ontario Geological Survey, Precambrian Geoscience Section, 933 Ramsey Lake Road, B7064 Sudbury, Ontario P3E 6B5, e-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Geology, Lamar University, Beaumont, Texas 77710, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The Geological Society of London Proposal for “…ending the distinction between the dual stratigraphic terminology of time-rock units (of chronostratigraphy) and geologic time units (of geochronology). The long held, but widely misunderstood distinc- tion between these two essentially parallel time scales has been rendered unnecessary by the adoption of the global stratotype sections and points (GSSP-golden spike) principle in defining intervals of geologic time within rock strata.” Our review of stratigraphic princi- ples, concepts, models and paradigms through history clearly shows that the GSL Proposal is flawed and if adopted will be of disservice to the stratigraphic community. We recommend the continued use of the dual stratigraphic terminology of chronostratigraphy and geochronology for the following reasons: (1) time-rock (chronostratigraphic) and geologic time (geochronologic) units are conceptually different; (2) the subtended time-rock’s unit space between its “golden spiked-marked” -

The Astronomical Theory of Climate and the Age of the Brunhes-Matuyama Magnetic Reversal

EPSL ELSEVIER Earth and Planetary Science Letters 126 (1994) 91-108 The astronomical theory of climate and the age of the Brunhes-Matuyama magnetic reversal Franck C. Bassinot a,1, Laurent D. Labeyrie b, Edith Vincent a, Xavier Quidelleur c Nicholas J. Shackleton d, Yves Lancelot a a Laboratoire de Gdologie du Quaternaire, CNRS-Luminy, Case 907, 13288 Marseille cddex 09, France b Centre des Faibles Radioactivit&, CNRS/CEA, Avenue de la Terrasse, BP 1, 91198 Gif-sur-Yvette, France c Institut de Physique du Globe, Laboratoire de Pal~omagn&isme, 4 Place Jussieu, 75252 Paris c~dex 05, France d Department of Quaternary Research, The Godwin Laboratory, Free School Lane, Cambridge CB2 3RS, UK Received 3 November 1993; revision accepted 30 May 1994 Abstract Below oxygen isotope stage 16, the orbitally derived time-scale developed by Shackleton et al. [1] from ODP site 677 in the equatorial Pacific differs significantly from previous ones [e.g., 2-5], yielding estimated ages for the last Earth magnetic reversals that are 5-7% older than the K/Ar values [6-8] but are in good agreement with recent Ar/Ar dating [9-11]. These results suggest that in the lower Brunhes and upper Matuyama chronozones most deep-sea climatic records retrieved so far apparently missed or misinterpreted several oscillations predicted by the astronomical theory of climate. To test this hypothesis, we studied a high-resolution oxygen isotope record from giant piston core MD900963 (Maldives area, tropical Indian Ocean) in which precession-related oscillations in t~180 are particularly well expressed, owing to the superimposition of a local salinity signal on the global ice volume signal [12]. -

Low-Cost Epoch-Based Correlation Prefetching for Commercial Applications Yuan Chou Architecture Technology Group Microelectronics Division

Low-Cost Epoch-Based Correlation Prefetching for Commercial Applications Yuan Chou Architecture Technology Group Microelectronics Division 1 Motivation Performance of many commercial applications limited by processor stalls due to off-chip cache misses Applications characterized by irregular control-flow and complex data access patterns Software prefetching and simple stride-based hardware prefetching ineffective Hardware correlation prefetching more promising - can remember complex recurring data access patterns Current correlation prefetchers have severe drawbacks but we think we can overcome them 2 Talk Outline Traditional Correlation Prefetching Epoch-Based Correlation Prefetching Experimental Results Summary 3 Traditional Correlation Prefetching Basic idea: use current miss address M to predict N future miss addresses F ...F (where N = prefetch depth) 1 N Miss address sequence: A B C D E F G H I assume N=2 Use A to prefetch B C Use D to prefetch E F Use G to prefetch H I Correlations recorded in correlation table Correlation table size proportional to application working set 4 Correlation Prefetching Drawbacks Very large correlation tables needed for commercial apps - impractical to store on-chip No attempt to eliminate all naturally overlapped misses Miss address sequence: A B C D E F G H I time A C F H B D G I E compute off-chip access 5 Correlation Prefetching Drawbacks Very large correlation tables needed for commercial apps - impractical to store on-chip No attempt to eliminate all naturally overlapped misses Miss address sequence: -

Treasury's Emergency Rental Assistance

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: TREASURY’SHEADING EMERGENCY1 HERE RENTAL ASSISTANCEHEADING (ERA)1 HERE PROGRAM AUGUST 2021 ongress established an Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) program administered by the U.S. Department of the Treasury to distribute critically needed emergency rent and utility assistance to Cmillions of households at risk of losing their homes. Congress provided more than $46 billion for emergency rental assistance through the Consolidated Appropriations Act enacted in December 2020 and the American Rescue Plan Act enacted in March 2021. Based on NLIHC’s ongoing tracking and analysis of state and local ERA programs, including nearly 500 programs funded through Treasury’s ERA program, NLIHC has continued to identify needed policy changes to ensure ERA is distributed efficiently, effectively, and equitably. The ability of states and localities to distribute ERA was hindered early on by harmful guidance released by the Trump administration on its last day in office. Immediately after President Biden was sworn into office, the administration rescinded the harmful FAQ and released improved guidance to ensure ERA reaches households with the greatest needs, as recommended by NLIHC. The Biden administration issued revised ERA guidance in February, March, May, June, and August that directly addressed many of NLIHC’s concerns about troubling roadblocks in ERA programs. Treasury’s latest guidance provides further clarity and recommendations to encourage state and local governments to expedite assistance. Most notably, the FAQ provides even more explicit permission for ERA grantees to rely on self-attestations without further documentation. WHO IS ELIGIBLE TO RECEIVE EMERGENCY RENTAL ASSISTANCE? Households are eligible for ERA funds if one or more individuals: 1. -

Geologic History of the Earth 1 the Precambrian

Geologic History of the Earth 1 algae = very simple plants that Geologists are scientists who study the structure grow in or near the water of rocks and the history of the Earth. By looking at first = in the beginning at and examining layers of rocks and the fossils basic = main, important they contain they are able to tell us what the beginning = start Earth looked like at a certain time in history and billion = a thousand million what kind of plants and animals lived at that breathe = to take air into your lungs and push it out again time. carbon dioxide = gas that is produced when you breathe Scientists think that the Earth was probably formed at the same time as the rest out of our solar system, about 4.6 billion years ago. The solar system may have be- certain = special gun as a cloud of dust, from which the sun and the planets evolved. Small par- complex = something that has ticles crashed into each other to create bigger objects, which then turned into many different parts smaller or larger planets. Our Earth is made up of three basic layers. The cen- consist of = to be made up of tre has a core made of iron and nickel. Around it is a thick layer of rock called contain = have in them the mantle and around that is a thin layer of rock called the crust. core = the hard centre of an object Over 4 billion years ago the Earth was totally different from the planet we live create = make on today. -

Lithostratigraphic Mapping Through Saprolitic Regolith Using Soil Geochemistry and High-Resolution Aeromagnetic Surveys

EGU2020-20242 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-20242 EGU General Assembly 2020 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Lithostratigraphic Mapping Through Saprolitic Regolith Using Soil Geochemistry and High-Resolution Aeromagnetic Surveys. Helen Twigg and Murray Hitzman iCRAG, School of Earth Sciences, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin, Ireland The Neoproterozoic Central African Copperbelt located in southern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the northwestern Zambia and contains 48% of the world’s cobalt reserves and significant resources of copper, zinc, nickel and gold. A good understanding of the geology is critical for successful mineral exploration. However, geological mapping is hindered by low topographic relief, limited outcrop, and a generally deep (10-100m) weathering profile developed since the Late Miocene. Multielement soil geochemistry provides a means for conducting geological mapping. Areas with outcrop or containing drill holes and/or trenches were utilized to relate known geological lithologies with soil geochemical results using major element and trace element ratios. The lithostratigraphy within a study area along the DRC-Zambia border can be geochemically sub- divided into three units. Mixed carbonate and siliciclastic lithologies of the lower portion of the local stratigraphy are typically characterised by elevated V, Ti, and Nb. Mudstones and siltstones are dominated by elevated Al, Fe and Ba. The upper portion of the local stratigraphy is geochemically neutral with regards to trace elements. Lithological discrimination through analysis of soil geochemical data is limited in some areas by intense weathering. A A-CNK-FM diagram exhibits how complete weathering of carbonate rocks and carbonate-rich breccias (after evaporites) results in the somewhat counter intuitive outcome that residual soils above carbonate rocks are amongst the most aluminum rich in the study area with >80% Al2O3 (mol%) or >80% combined Al2O3 (mol%) and FeO + MgO (mol%). -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

The Paleontology Synthesis Project and Establishing a Framework for Managing National Park Service Paleontological Resource Archives and Data

Lucas, S.G. and Sullivan, R.M., eds., 2018, Fossil Record 6. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 79. 589 THE PALEONTOLOGY SYNTHESIS PROJECT AND ESTABLISHING A FRAMEWORK FOR MANAGING NATIONAL PARK SERVICE PALEONTOLOGICAL RESOURCE ARCHIVES AND DATA VINCENT L. SANTUCCI1, JUSTIN S. TWEET2 and TIMOTHY B. CONNORS3 1National Park Service, Geologic Resources Division, 1849 “C” Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20240, [email protected]; 2National Park Service, 9149 79th Street S., Cottage Grove, MN 55016, [email protected]; 3National Park Service, Geologic Resources Division, 12795 W. Alameda Parkway, Lakewood, CO 80225, [email protected] Abstract—The National Park Service Paleontology Program maintains an extensive collection of digital and hard copy documents, publications, photographs and other archives associated with the paleontological resources documented in 268 parks. The organization and preservation of the NPS paleontology archives has been the focus of intensive data management activities by a small and dedicated team of NPS staff. The data preservation strategy complemented the NPS servicewide inventories for paleontological resources. The first phase of the data management, referred to as the NPS Paleontology Synthesis Project, compiled servicewide paleontological resource data pertaining to geologic time, taxonomy, museum repositories, holotype fossil specimens, and numerous other topics. In 2015, the second phase of data management was implemented with the creation and organization of a multi-faceted digital data system known as the NPS Paleontology Archives and NPS Paleontology Library. Two components of the NPS Paleontology Archives were designed for the preservation of both park specific and servicewide paleontological resource archives and data. A third component, the NPS Paleontology Library, is a repository for electronic copies of geology and paleontology publications, reports, and other media. -

Mechanical Stratigraphic Controls on Natural Fracture Spacing and Penetration

Journal of Structural Geology 95 (2017) 160e170 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Structural Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jsg Mechanical stratigraphic controls on natural fracture spacing and penetration * Ronald N. McGinnis a, , David A. Ferrill a, Alan P. Morris a, Kevin J. Smart a, Daniel Lehrmann b a Department of Earth, Material, and Planetary Sciences, Southwest Research Institute, 6220 Culebra Road, San Antonio, TX 78238-5166, USA b Geoscience Department, Trinity University, One Trinity Place, San Antonio, TX 78212, USA article info abstract Article history: Fine-grained low permeability sedimentary rocks, such as shale and mudrock, have drawn attention as Received 20 July 2016 unconventional hydrocarbon reservoirs. Fracturing e both natural and induced e is extremely important Received in revised form for increasing permeability in otherwise low-permeability rock. We analyze natural extension fracture 21 December 2016 networks within a complete measured outcrop section of the Ernst Member of the Boquillas Formation Accepted 7 January 2017 in Big Bend National Park, west Texas. Results of bed-center, dip-parallel scanline surveys demonstrate Available online 8 January 2017 nearly identical fracture strikes and slight variation in dip between mudrock, chalk, and limestone beds. Fracture spacing tends to increase proportional to bed thickness in limestone and chalk beds; however, Keywords: Mechanical stratigraphy dramatic differences in fracture spacing are observed in mudrock. A direct relationship is observed be- Natural fractures tween fracture spacing/thickness ratio and rock competence. Vertical fracture penetrations measured Fracture spacing from the middle of chalk and limestone beds generally extend to and often beyond bed boundaries into Fracture penetration the vertically adjacent mudrock beds. -

Soils in the Geologic Record

in the Geologic Record 2021 Soils Planner Natural Resources Conservation Service Words From the Deputy Chief Soils are essential for life on Earth. They are the source of nutrients for plants, the medium that stores and releases water to plants, and the material in which plants anchor to the Earth’s surface. Soils filter pollutants and thereby purify water, store atmospheric carbon and thereby reduce greenhouse gasses, and support structures and thereby provide the foundation on which civilization erects buildings and constructs roads. Given the vast On February 2, 2020, the USDA, Natural importance of soil, it’s no wonder that the U.S. Government has Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) an agency, NRCS, devoted to preserving this essential resource. welcomed Dr. Luis “Louie” Tupas as the NRCS Deputy Chief for Soil Science and Resource Less widely recognized than the value of soil in maintaining Assessment. Dr. Tupas brings knowledge and experience of global change and climate impacts life is the importance of the knowledge gained from soils in the on agriculture, forestry, and other landscapes to the geologic record. Fossil soils, or “paleosols,” help us understand NRCS. He has been with USDA since 2004. the history of the Earth. This planner focuses on these soils in the geologic record. It provides examples of how paleosols can retain Dr. Tupas, a career member of the Senior Executive Service since 2014, served as the Deputy Director information about climates and ecosystems of the prehistoric for Bioenergy, Climate, and Environment, the Acting past. By understanding this deep history, we can obtain a better Deputy Director for Food Science and Nutrition, and understanding of modern climate, current biodiversity, and the Director for International Programs at USDA, ongoing soil formation and destruction. -

Equivalence of Current–Carrying Coils and Magnets; Magnetic Dipoles; - Law of Attraction and Repulsion, Definition of the Ampere

GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) THE EARTH'S MAGNETIC FIELD OUTLINE Magnetism Magnetic forces: - equivalence of current–carrying coils and magnets; magnetic dipoles; - law of attraction and repulsion, definition of the ampere. Magnetic fields: - magnetic fields from electrical currents and magnets; magnetic induction B and lines of magnetic induction. The geomagnetic field The magnetic elements: (N, E, V) vector components; declination (azimuth) and inclination (dip). The external field: diurnal variations, ionospheric currents, magnetic storms, sunspot activity. The internal field: the dipole and non–dipole fields, secular variations, the geocentric axial dipole hypothesis, geomagnetic reversals, seabed magnetic anomalies, The dynamo model Reasons against an origin in the crust or mantle and reasons suggesting an origin in the fluid outer core. Magnetohydrodynamic dynamo models: motion and eddy currents in the fluid core, mechanical analogues. Background reading: Fowler §3.1 & 7.9.2, Lowrie §5.2 & 5.4 GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) MAGNETIC FORCES Magnetic forces are forces associated with the motion of electric charges, either as electric currents in conductors or, in the case of magnetic materials, as the orbital and spin motions of electrons in atoms. Although the concept of a magnetic pole is sometimes useful, it is diácult to relate precisely to observation; for example, all attempts to find a magnetic monopole have failed, and the model of permanent magnets as magnetic dipoles with north and south poles is not particularly accurate. Consequently moving charges are normally regarded as fundamental in magnetism. Basic observations 1. Permanent magnets A magnet attracts iron and steel, the attraction being most marked close to its ends. -

International Chronostratigraphic Chart

INTERNATIONAL CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHIC CHART www.stratigraphy.org International Commission on Stratigraphy v 2015/01 numerical numerical numerical Eonothem numerical Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age Erathem / Era System / Period GSSP GSSP age (Ma) GSSP GSSA EonothemErathem / Eon System / Era / Period EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) / Eon GSSP age (Ma) present ~ 145.0 358.9 ± 0.4 ~ 541.0 ±1.0 Holocene Ediacaran 0.0117 Tithonian Upper 152.1 ±0.9 Famennian ~ 635 0.126 Upper Kimmeridgian Neo- Cryogenian Middle 157.3 ±1.0 Upper proterozoic ~ 720 Pleistocene 0.781 372.2 ±1.6 Calabrian Oxfordian Tonian 1.80 163.5 ±1.0 Frasnian 1000 Callovian 166.1 ±1.2 Quaternary Gelasian 2.58 382.7 ±1.6 Stenian Bathonian 168.3 ±1.3 Piacenzian Middle Bajocian Givetian 1200 Pliocene 3.600 170.3 ±1.4 Middle 387.7 ±0.8 Meso- Zanclean Aalenian proterozoic Ectasian 5.333 174.1 ±1.0 Eifelian 1400 Messinian Jurassic 393.3 ±1.2 7.246 Toarcian Calymmian Tortonian 182.7 ±0.7 Emsian 1600 11.63 Pliensbachian Statherian Lower 407.6 ±2.6 Serravallian 13.82 190.8 ±1.0 Lower 1800 Miocene Pragian 410.8 ±2.8 Langhian Sinemurian Proterozoic Neogene 15.97 Orosirian 199.3 ±0.3 Lochkovian Paleo- Hettangian 2050 Burdigalian 201.3 ±0.2 419.2 ±3.2 proterozoic 20.44 Mesozoic Rhaetian Pridoli Rhyacian Aquitanian 423.0 ±2.3 23.03 ~ 208.5 Ludfordian 2300 Cenozoic Chattian Ludlow 425.6 ±0.9 Siderian 28.1 Gorstian Oligocene Upper Norian 427.4 ±0.5 2500 Rupelian Wenlock Homerian