Springtails in Sugarbeet: Identification, Biology, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Changing of the Guard in White Grub Control Insecticides

A PRACTICAL RESEARCH DIGEST FOR TURF MANAGERS Volume 10, Issue 6 • June 2001 ¡TURFGRASS PEST CONTROL IN THIS ISSUE • The changing of the The Changing of the guard in white grub Guard in White Grub control insecticides 1 Organophosphate/ Control Insecticides carbamate update New product information By Kevin Mathias Natural control influence of insecticides combination of federal regulatory rulings and economic decisions by insecticide Multiple targeting manufacturers has dramatically changed the landscape of white grub insecticides A and control strategies. At the beginning of the 1990's white grub control insecti- • Site analysis for golf cides consisted mainly of organophosphate and carbamate based chemistries with only a course development 7 few biorational products available (Table 1). As a group, the organophosphate and car- Climate bamate insecticides, have a relatively short residual activity and are highly efficacious when used in curative control programs. Topography Optimum results are attained if the products are applied in mid to late August or into September, as white grub damage is first noticed and Drainage patterns when the grubs are young and relatively small. Optimum results are Water availability As we enter the new millennium many of the cura- attained if the tive control products have been replaced by a group of Soils and geology products are applied new insecticides. These insecticides, Merit and Mach 2, offer greater applicator safety, have less adverse effect Environmental issues in mid to late August on the environment, provide a longer window of appli- Wetlands or into September, as cation due to their extended soil residual activities, have minimal impact on beneficial predators, and pro- Water quality white grub damage vide excellent control (+90%) of white grubs. -

13 Index of Common Names

Index of Common Names BITING/STINGING/VENOMOUS PESTS Bees ………………………………………………………… 6 Honey bee…………………………………………………6 Africanized bees……………………………………….. 7 Bumblebee…………………………………………………….9 Carpenter bee……………………………………………….9 Digger bee………………………………………………………11 Leaf cutter bee………………………………………………….12 Sweat bee………………………………………………………..13 Wasps…………………………………………………………….14 Tarantula hawk…………………………………………………14 Yellowjacket……………………………………………………….15 Aerial yellowjacket ……………………………………………….15,16 Common yellowjacket ……………………………………………….15 German yellowjacket……………………………………………….15 Western yellowjacket……………………………………………….15 Paper wasp………………………………………………. 18 Brown paper wasp……………………………………………….18 Common paper wasp ……………………………………………….18 European paper wasp……………………………………………….18 Navajo paper wasp……………………………………………….18,19 Yellow paper wasp……………………………………………….18,19 Western paper wasp……………………………………………….18 Mud dauber………………………………………………. 20 Black and blue mud dauber……………………………..………………….20 Black and yellow mud dauber……………………………………………….20 Organ pipe mud dauber……………………………………………….20,21 Velvet ant……………………………………………………21 Scorpions………………………………………………………23 Arizona bark scorpion……………………………………………….23 Giant hairy scorpion ……………………………………………….24 Striped-tail scorpion……………………………………………….25 Yellow ground scorpion……………………………………………….25 Spiders…………………………………………………………..26 Cellar spider……………………………………………….2 6 Recluse spider……………………………………………….27 Tarantula…………………………………………………. 28 Widow spider……………………………………………….29 Scorpion/spider look-alikes……………………………………………….30 Pseudoscorpion……………………………………………….30 Solifugid/wind -

Observations on the Springtail Leaping Organ and Jumping Mechanism Worked by a Spring

Observations on the Springtail Leaping Organ and Jumping Mechanism Worked by a Spring Seiichi Sudo a*, Masahiro Shiono a, Toshiya Kainuma a, Atsushi Shirai b, and Toshiyuki Hayase b a Faculty of Systems Science and Technology, Akita Prefectural University, Japan b Institute of Fluid Science, Tohoku University, Japan Abstract— This paper is concerned with a small In this paper, the springtail leaping organ was jumping mechanism. Microscopic observations of observed with confocal laser scanning microscopy. A springtail leaping organs were conducted using a jumping mechanism using a spring and small confocal leaser scanning microscope. A simple electromagnet was produced based on the observations springtail mechanism using a spring and small of leaping organ and the jumping analysis of the electromagnet was produced based on the observations springtail. of leaping organ and the jumping analysis of the globular springtail. Jumping characteristics of the mechanism were examined with high-speed video II. EXPERIMENTAL METHOD camera system. A. Microscopic Observations Index Terms—Jumping Mechanism, Leaping Organ, Globular springtails are small insects that reach Springtail, Morphology, Jumping Characteristics around 1 mm in size. They have the jumping organ (furcula), which can be folded under the abdomen. Muscular action releasing the furcula can throw the I. INTRODUCTION insect well out of the way of predators. Jumping in insect movement is an effective way to In this paper, microscopic observations of the furcula escape predators, find food, and change locations. were conducted using the confocal laser scanning Grasshoppers, fleas, bush crickets, katydids, and locusts microscope. Confocal laser scanning microscopy is are particularly well known for jumping mechanisms to fluorescence – imaging technique that produces move around. -

Occasional Invaders

This publication is no longer circulated. It is preserved here for archival purposes. Current information is at https://extension.umd.edu/hgic HG 8 2000 Occasional Invaders Centipedes Centipede Millipede doors and screens, and by removal of decaying vegetation, House Centipede leaf litter, and mulch from around the foundations of homes. Vacuum up those that enter the home and dispose of the bag outdoors. If they become intolerable and chemical treatment becomes necessary, residual insecticides may be Centipedes are elongate, flattened animals with one pair of used sparingly. Poisons baits may be used outdoors with legs per body segment. The number of legs may vary from caution, particularly if there are children or pets in the home. 10 to over 100, depending on the species. They also have A residual insecticide spray applied across a door threshold long jointed antennae. The house centipede is about an inch may prevent the millipedes from entering the house. long, gray, with very long legs. It lives outdoors as well as indoors, and may be found in bathrooms, damp basements, Sowbugs and Pillbugs closets, etc. it feeds on insects and spiders. If you see a centipede indoors, and can’t live with it, escort it outdoors. Sowbugs and pillbugs are the only crustaceans that have Centipedes are beneficial by helping controlArchived insect pests and adapted to a life on land. They are oval in shape, convex spiders. above, and flat beneath. They are gray in color, and 1/2 to 3/4 of an inch long. Sowbugs have two small tail-like Millipedes appendages at the rear, and pillbugs do not. -

Springtails1 P

ENY-228 Springtails1 P. G. Koehler, M. L. Aparicio, and M. Pfiester2 organic material and other nutrients to return to the soil; these nutrients are later used by plants. Occasionally, springtails attack young seedlings and may damage the roots and stems. Biology and Description The Order Collembola has two suborders easily distin- guished by their body shape. One appears linear (Figure 1), while the other appears globular (Figure 2). These suborders are further divided into families that contain the separate species. Only seven families include the 650 species in North America. Worldwide, 3,600 species have been discovered. This fact sheet is included in SP134: Pests in and around the Florida Home, which is available from the UF/IFAS Extension Bookstore. http:// ifasbooks.ifas.ufl.edu/p-154-pests-in-andaroundthe-florida-home.aspx Figure 1. A linear springtail. Springtails are minute insects without wings in the Order Springtails range in length from 0.25 to 6 mm, but are Collembola. They occur in large numbers in moist soil and normally about 1 mm long. Colors range from white to can be found in homes with high humidity, organic debris, yellow, gray, or blue-gray. Attached to the tip of the abdo- or mold. Homeowners sometimes discover these insects men is a forked appendage resembling a lever and called occurring in large numbers in swimming pools, potted the furcula. At rest, a clasp called the tenaculum holds the plants, or in moist soil and mulch. They feed on fungi, furcula to the abdomen. When disturbed or threatened, fungal spores, and decaying, damp vegetation, causing the springtail’s tenaculum releases the furcula, which then 1. -

10010 Processing Mites and Springtails

Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute www.abmi.ca Processing Mites (Oribatids) and Springtails (Collembola) Version 2009-05-08 May 2009 ALBERTA BIODIVERSITY MONITORING INSTITUTE Acknowledgements Jeff Battegelli reviewed the literature and suggested protocols for sampling mites and springtails. These protocols were refined based on field testing and input from Heather Proctor. The present document was developed by Curtis Stambaugh and Christina Sobol, with the training material compiled by Brian Carabine. Jim Schieck provided input on earlier drafts of the present document. Updates to this document were incorporated by Dave Walter and Robert Hinchliffe. Disclaimer These standards and protocols were developed and released by the ABMI. The material in this publication does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of any individual or organization other than the ABMI. Moreover, the methods described in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the individual scientists participating in methodological development or review. Errors, omissions, or inconsistencies in this publication are the sole responsibility of ABMI. The ABMI assumes no liability in connection with the information products or services made available by the Institute. While every effort is made to ensure the information contained in these products and services is correct, the ABMI disclaims any liability in negligence or otherwise for any loss or damage which may occur as a result of reliance on any of this material. All information products and services are subject to change by the ABMI without notice. Suggested Citation: Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute, 2009. Processing Mites and Springtails (10010), Version 2009-05-08. -

A Seasonal Guide to New York City's Invertebrates

CENTER FOR BIODIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION A Seasonal Guide to New York City’s Invertebrates Elizabeth A. Johnson with illustrations by Patricia J. Wynne CENTER FOR BIODIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION A Seasonal Guide to New York City’s Invertebrates Elizabeth A. Johnson with illustrations by Patricia J. Wynne Ellen V. Futter, President Lewis W. Bernard, Chairman, Board of Trustees Michael J. Novacek, Senior Vice-President and Provost of Science TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.................................................................................2-3 Rules for Exploring When to Look Where to Look Spring.........................................................................................4-11 Summer ...................................................................................12-19 Fall ............................................................................................20-27 Winter ......................................................................................28-35 What You Can Do to Protect Invertebrates.............................36 Learn More About Invertebrates..............................................37 Map of Places Mentioned in the Text ......................................38 Thanks to all those naturalists who contributed information and to our many helpful reviewers: John Ascher, Allen Barlow, James Carpenter, Kefyn Catley, Rick Cech, Mickey Maxwell Cohen, Robert Daniels, Mike Feller, Steven Glenn, David Grimaldi, Jay Holmes, Michael May, E.J. McAdams, Timothy McCabe, Bonnie McGuire, Ellen Pehek, Don -

GENERAL HOUSEHOLD PESTS Ants Are Some of the Most Ubiquitous Insects Found in Community Environments. They Thrive Indoors and O

GENERAL HOUSEHOLD PESTS Ants are some of the most ubiquitous insects found in community environments. They thrive indoors and outdoors, wherever they have access to food and water. Ants outdoors are mostly beneficial, as they act as scavengers and decomposers of organic matter, predators of small insects and seed dispersers of certain plants. However, they can protect and encourage honeydew-producing insects such as mealy bugs, aphids and scales that are feed on landscape or indoor plants, and this often leads to increase in numbers of these pests. A well-known feature of ants is their sociality, which is also found in many of their close relatives within the order Hymenoptera, such as bees and wasps. Ant colonies vary widely with the species, and may consist of less than 100 individuals in small concealed spaces, to millions of individuals in large mounds that cover several square feet in area. Functions within the colony are carried out by specific groups of adult individuals called ‘castes’. Most ant colonies have fertile males called “drones”, one or more fertile females called “queens” and large numbers of sterile, wingless females which function as “workers”. Many ant species exhibit polymorphism, which is the existence of individuals with different appearances (sizes) and functions within the same caste. For example, the worker caste may include “major” and “minor” workers with distinct functions, and “soldiers” that are specially equipped with larger mandibles for defense. Almost all functions in the colony apart from reproduction, such as gathering food, feeding and caring for larvae, defending the colony, building and maintaining nesting areas, are performed by the workers. -

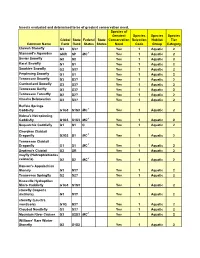

Insects Evaluated and Determined to Be of Greatest Conservation Need

Insects evaluated and determined to be of greatest conservation need. Species of Greatest Species Species Species Global State Federal State Conservation Selection Habitat Tier Common Name Rank Rank Status Status Need Code Group Category Etowah Stonefly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Stannard's Agarodes GNR SP MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Sevier Snowfly G2 S2 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Karst Snowfly G1 S1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Smokies Snowfly G2 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Perplexing Snowfly G1 S1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Snowfly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Cumberland Snowfly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Sallfly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Forestfly G2 S2? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Cheaha Beloneurian G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Buffalo Springs Caddisfly G1G3 S1S3 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Helma's Net-spinning Caddisfly G1G3 S1S3 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Sequatchie Caddisfly G1 S1 C Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Cherokee Clubtail Dragonfly G2G3 S1 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Clubtail Dragonfly G1 S1 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Septima's Clubtail G2 SR Yes 1 Aquatic 2 mayfly (Habrophlebiodes celeteria) G2 S2 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Hanson's Appalachian Stonely G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Springfly G2 S2? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Knoxville Hydroptilan Micro Caddisfly G1G3 S1S3 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 stonefly (Isoperla distincta) G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 stonefly (Leuctra monticola) G1Q S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Clouded Needlefly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Mountain River Cruiser G3 S2S3 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Williams' Rare Winter Stonefly G2 S1S2 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Con't...Insects evaluated and determined to be of greatest conservation need. -

Marine Insects

UC San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography Technical Report Title Marine Insects Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1pm1485b Author Cheng, Lanna Publication Date 1976 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Marine Insects Edited by LannaCheng Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, La Jolla, Calif. 92093, U.S.A. NORTH-HOLLANDPUBLISHINGCOMPANAY, AMSTERDAM- OXFORD AMERICANELSEVIERPUBLISHINGCOMPANY , NEWYORK © North-Holland Publishing Company - 1976 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,without the prior permission of the copyright owner. North-Holland ISBN: 0 7204 0581 5 American Elsevier ISBN: 0444 11213 8 PUBLISHERS: NORTH-HOLLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY - AMSTERDAM NORTH-HOLLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY LTD. - OXFORD SOLEDISTRIBUTORSFORTHEU.S.A.ANDCANADA: AMERICAN ELSEVIER PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC . 52 VANDERBILT AVENUE, NEW YORK, N.Y. 10017 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Marine insects. Includes indexes. 1. Insects, Marine. I. Cheng, Lanna. QL463.M25 595.700902 76-17123 ISBN 0-444-11213-8 Preface In a book of this kind, it would be difficult to achieve a uniform treatment for each of the groups of insects discussed. The contents of each chapter generally reflect the special interests of the contributors. Some have presented a detailed taxonomic review of the families concerned; some have referred the readers to standard taxonomic works, in view of the breadth and complexity of the subject concerned, and have concentrated on ecological or physiological aspects; others have chosen to review insects of a specific set of habitats. -

Homologous Neurons in Arthropods 2329

Development 126, 2327-2334 (1999) 2327 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1999 DEV8572 Analysis of molecular marker expression reveals neuronal homology in distantly related arthropods Molly Duman-Scheel1 and Nipam H. Patel2,* 1Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, University of Chicago, 920 East 58th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA 2Department of Anatomy and Organismal Biology and HHMI, University of Chicago, MC1028, AMBN101, 5841 South Maryland Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 16 March; published on WWW 4 May 1999 SUMMARY Morphological studies suggest that insects and crustaceans markers, across a number of arthropod species. This of the Class Malacostraca (such as crayfish) share a set of molecular analysis allows us to verify the homology of homologous neurons. However, expression of molecular previously identified malacostracan neurons and to identify markers in these neurons has not been investigated, and the additional homologous neurons in malacostracans, homology of insect and malacostracan neuroblasts, the collembolans and branchiopods. Engrailed expression in neural stem cells that produce these neurons, has been the neural stem cells of a number of crustaceans was also questioned. Furthermore, it is not known whether found to be conserved. We conclude that despite their crustaceans of the Class Branchiopoda (such as brine distant phylogenetic relationships and divergent shrimp) or arthropods of the Order Collembola mechanisms of neurogenesis, insects, malacostracans, (springtails) possess neurons that are homologous to those branchiopods and collembolans share many common CNS of other arthropods. Assaying expression of molecular components. markers in the developing nervous systems of various arthropods could resolve some of these issues. -

<I>Orchesella</I> (Collembola: Entomobryomorpha

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2015 A Molecular and Morphological Investigation of the Springtail Genus Orchesella (Collembola: Entomobryomorpha: Entomobryidae) Catherine Louise Smith University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Catherine Louise, "A Molecular and Morphological Investigation of the Springtail Genus Orchesella (Collembola: Entomobryomorpha: Entomobryidae). " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3410 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Catherine Louise Smith entitled "A Molecular and Morphological Investigation of the Springtail Genus Orchesella (Collembola: Entomobryomorpha: Entomobryidae)." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Entomology and Plant Pathology. John K. Moulton, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Ernest C. Bernard, Juan Luis Jurat-Fuentes Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) A Molecular and Morphological Investigation of the Springtail Genus Orchesella (Collembola: Entomobryomorpha: Entomobryidae) A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Catherine Louise Smith May 2015 Copyright © 2014 by Catherine Louise Smith All rights reserved.