Methodist Chapels in Jersey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Peter Q3 2020.Pdf

The Jersey Boys’ lastSee Page 16 march Autumn2020 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Featured What’s new in St Peter? Very little - things have gone Welcomereally quiet it seems, so far as my in-box is concerned anyway. Although ARTICLES the Island has moved to Level 1 of the Safe Exit Framework and many businesses are returning to some kind of normal, the same cannot be said of the various associations within the Parish, as you will see from 6 Helping Wings hope to fly again the rather short contributions from a few of the groups who were able to send me something. Hopefully this will change in the not too distant future, when social distancing returns to normal. There will be a lot of 8 Please don’t feed the Seagulls catching up to do and, I am sure, much news to share in Les Clefs. Closed shops So in this autumn edition, a pretty full 44 pages, there are some 10 offerings from the past which I hope will provide some interesting reading and visual delight. With no Battle of Flowers parades this year, 12 Cash for Trash – Money back on Bottles? there’s a look back at the 28 exhibits the Parish has entered since 1986. Former Constable Mac Pollard shares his knowledge and experiences about St Peter’s Barracks and ‘The Jersey Boys’, and we learn how the 16 The Jersey Boys last march retail sector in the Parish has changed over the years with an article by Neville Renouf on closed shops – no, not the kind reserved for union members only! We also learn a little about the ‘green menace’ in St 20 Hey Mr Bass Man Aubin’s Bay and how to refer to and pronounce it in Jersey French, and after several complaints have been received at the Parish Hall, some 22 Floating through time information on what we should be doing about seagulls. -

Dégrèvement and Réalisation Information for the Litigant in Person

The Jersey Court Service Judicial Greffe & Viscount’s Department Dégrèvement and Réalisation: Information for the Litigant in Person e] This document outlines the legal proceedings known as dégrèvement, setting out the options available to a debtor at each stage of the process. Much has been simplified or omitted, and the laws governing the procedures mentioned must be read, and appropriate professional advice obtained, to obtain an accurate picture of what the law is. You are advised to obtain legal advice in relation to your particular circumstances. Legal Aid in Jersey is administered by the Acting Bâtonnier, whose offices are at 40 Don Street, St Helier, Jersey. Tel: +44 (0)845 8001066 Fax: +44 (0)1534 601708 Website: www.legalaid.je Email: [email protected] Before applying for Legal Aid you should make sure that you have read and understood the form headed Notes for Legal Aid Applicants, available at www.legalaid.je as a download. April 2016 Dégrèvement and réalisation: Information for the Litigant in Person April 2016 Contents 1. Dégrèvement and réalisation .......................................................................................................... 2 2. Key terminology .............................................................................................................................. 2 3. Why would a secured creditor apply for a dégrèvement ? .............................................................. 4 4. The dégrèvement procedure .......................................................................................................... -

The Linguistic Context 34

Variation and Change in Mainland and Insular Norman Empirical Approaches to Linguistic Theory Series Editor Brian D. Joseph (The Ohio State University, USA) Editorial Board Artemis Alexiadou (University of Stuttgart, Germany) Harald Baayen (University of Alberta, Canada) Pier Marco Bertinetto (Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, Italy) Kirk Hazen (West Virginia University, Morgantown, USA) Maria Polinsky (Harvard University, Cambridge, USA) Volume 7 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ealt Variation and Change in Mainland and Insular Norman A Study of Superstrate Influence By Mari C. Jones LEIDEN | BOSTON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jones, Mari C. Variation and Change in Mainland and Insular Norman : a study of superstrate influence / By Mari C. Jones. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25712-2 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-25713-9 (e-book) 1. French language— Variation. 2. French language—Dialects—Channel Islands. 3. Norman dialect—Variation. 4. French language—Dialects—France—Normandy. 5. Norman dialect—Channel Islands. 6. Channel Islands— Languages. 7. Normandy—Languages. I. Title. PC2074.7.J66 2014 447’.01—dc23 2014032281 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 2210-6243 ISBN 978-90-04-25712-2 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25713-9 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff and Hotei Publishing. -

Biodiversity Strategy for Jersey

Bio Diversity a strategy for Jersey Forward by Senator Nigel Quérée President, Planning and Environment Committee This document succeeds in bringing together all the facets of Jersey’s uniquely diverse environmental landscape. It describes the contrasting habitats which exist in this small Island and explains what should be done to preserve them, so that we can truly hand Jersey on to future generations with minimal environmental damage. It is a document which should be read by anyone who wants to know more about the different species which exist in Jersey and what should be done to protect them. I hope that it will help to foster a much greater understanding of the delicate balance that should be struck when development in the Island is considered and for that reason this is a valuable supporting tool for the Jersey Island Plan. Introduction Section 4 Loss of biodiversity and other issues Section 1 Causes of Loss of Biodiversity 33 The structure of the strategy Conservation Issues 34 Biodiversity 1 In Situ/Ex Situ Conservation 34 Biodiversity and Jersey 2 EIA Procedures in Jersey 36 Methodology 2 Role of Environmental Adviser 36 Approach 3 International Relations 38 Process 3 Contingency Planning 38 Key International Obligations 3 Current Legislation 5 Section 5 Evaluation of Natural History Sites 5 In situ conservation Introduction 42 Section 2 Habitats 42 Sustainable use Species 46 Introduction 9 The Identification of Key Species 47 General Principles 9 Limitations 48 Scope of Concern 11 Species Action Plans 49 Sample Action Plan 51 -

48 St Saviour Q3 2020.Pdf

Autumn2020 Esprit de St Sauveur Edition 48 farewellA fond Rectorto our wonderful Page 30 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Autumn 2020 St Saviour Parish Magazine p3 From the Editor Featured Back on Track! articles La Cloche is back on track and we have a full magazine. There are some poems by local From the Constable poets to celebrate Liberation and some stories from St Saviour residents who were in Jersey when the Liberation forces arrived on that memorable day, 9th May 1945. It is always enlightening to read and hear of others’ stories from the Occupation and Liberation p4 of Jersey during the 1940s. Life was so very different then, from now, and it is difficult for us to imagine what life was really like for the children and adults living at that time. Giles Bois has submitted a most interesting article when St Saviour had to build a guardhouse on the south coast. The Parish was asked to help Grouville with patrolling Liberation Stories the coast looking for marauders and in 1690 both parishes were ordered to build a guardhouse at La Rocque. This article is a very good read and the historians among you will want to rush off to look for our Guardhouse! Photographs accompany the article to p11 illustrate the building in the early years and then later development. St Saviour Battle of Flowers Association is managing to keep itself alive with a picnic in St Paul’s Football Club playing field. They are also making their own paper flowers in different styles and designs; so please get in touch with the Association Secretary to help with Forever St Saviour making flowers for next year’s Battle. -

Jersey's Spiritual Landscape

Unlock the Island with Jersey Heritage audio tours La Pouquelaye de Faldouët P 04 Built around 6,000 years ago, the dolmen at La Pouquelaye de Faldouët consists of a 5 metre long passage leading into an unusual double chamber. At the entrance you will notice the remains of two dry stone walls and a ring of upright stones that were constructed around the dolmen. Walk along the entrance passage and enter the spacious circular main Jersey’s maritime Jersey’s military chamber. It is unlikely that this was ever landscape landscape roofed because of its size and it is easy Immerse Download the FREE audio tour Immerse Download the FREE audio tour to imagine prehistoric people gathering yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org the history the history here to worship and perform rituals. and stories and stories of Jersey of Jersey La Hougue Bie N 04 The 6,000-year-old burial site at Supported by Supported by La Hougue Bie is considered one of Tourism Development Fund Tourism Development Fund the largest and best preserved Neolithic passage graves in Europe. It stands under an impressive mound that is 12 metres high and 54 metres in diameter. The chapel of Notre Dame de la Clarté Jersey’s Maritime Landscape on the summit of the mound was Listen to fishy tales and delve into Jersey’s maritime built in the 12th century, possibly Jersey’s spiritual replacing an older wooden structure. past. Audio tour and map In the 1990s, the original entrance Jersey’s Military Landscape to the passage was exposed during landscape new excavations of the mound. -

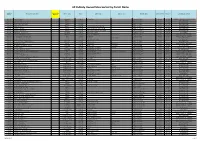

All Publicly Owned Sites Sorted by Parish Name

All Publicly Owned Sites Sorted by Parish Name Sorted by Proposed for Then Sorted by Site Name Site Use Class Tenure Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Vingtaine Name Address Parish Postcode Controlling Department Parish Disposal Grouville 2 La Croix Crescent Residential Freehold La Rue a Don Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DA COMMUNITY & CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS Grouville B22 Gorey Village Highway Freehold Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9EB INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B37 La Hougue Bie - La Rocque Highway Freehold Vingtaine de la Rue Grouville JE3 9UR INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B70 Rue a Don - Mont Gabard Highway Freehold Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 6ET INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B71 Rue des Pres Highway Freehold La Croix - Rue de la Ville es Renauds Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DJ INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville C109 Rue de la Parade Highway Freehold La Croix Catelain - Princes Tower Road Vingtaine de Longueville Grouville JE3 9UP INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville C111 Rue du Puits Mahaut Highway Freehold Grande Route des Sablons - Rue du Pont Vingtaine de la Rocque Grouville JE3 9BU INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville Field G724 Le Pre de la Reine Agricultural Freehold La Route de Longueville Vingtaine de Longueville Grouville JE2 7SA ENVIRONMENT Grouville Fields G34 and G37 Queen`s Valley Agricultural Freehold La Route de la Hougue Bie Queen`s Valley Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9EW HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES Grouville Fort William Beach Kiosk Sites 1 & 2 Land Freehold La Rue a Don Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DY JERSEY PROPERTY HOLDINGS -

Treasure Exhibition Objects

Treasure Exhibition Objects The main focus of the exhibition is the Coin Hoard found in 2012. This is displayed in a conservation laboratory in the middle of the exhibition. There is live conservation ongoing to the Le Catillon Hoard II. Coins are being taken off the main hoard, cleaned, identified and then catalogued and packaged. The rest of the exhibition contains items from Jersey, Guernsey, Sark , Alderney and France from both the Romans and the Celts. l The rest of the exhibition contains items from The ship timbers from Guernsey Jersey, Guernsey, Sark , Alderney and France from l The Orval Chariot Burial from France both the Romans and the Celts. l Coins from Le Catillon Hoard I from Grouville The amount of items from bothe the cultures l Paule Statues from Brittany show their similarities and differences. They l Kings Road burials from Guernsey also demonstrate the variety of objects found archaeologically in these areas. The below list gives you details of every artefact There are a number of artefacts of particular within the exhibition. significance: Orval Chariot Burial Iron ring bolts, possibly elements connected with the chariot shaft. Five copper alloy phalerae decorated with small carved coral plaques, mounted on their support Iron hoops intended to strengthen the hub of each with a birch resin-based glue, occasionally finished of the two wheels. off with a small bronze rivet. (metal disc used to Iron eye bolts and forked rod which were probably adorn the harness) used as shock absorbers between the axel and the Two rein rings. carriage. Two copper alloy harness rings. -

UK23001 Page 1 of 13 South East Coast of Jersey, Channel Islands

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 7, 2nd edition, as amended by COP9 Resolution IX.1 Annex B). A 3rd edition of the Handbook, incorporating these amendments, is in preparation and will be available in 2006. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the Official Respondent: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. Joint Nature Conservation Committee DD MM YY Monkstone House City Road Peterborough Designation date Site Reference Number Cambridgeshire PE1 1JY UK Telephone/Fax: +44 (0)1733 – 562 626 / +44 (0)1733 – 555 948 Email: [email protected] Name and address of the compiler of this form: UK Overseas Territories Conservation Forum, 102 Broadway, Peterborough, PE1 4DG, UK 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: Designated: 25 September 2000 3. -

States of Jersey

STATES OF JERSEY Economic Affairs Jersey Telecom Privatisation Sub-Panel MONDAY, 17th DECEMBER 2007 Panel: Deputy G.P. Southern of St. Helier (Chairman) Deputy J.A. Martin of St. Helier Deputy G.C.L. Baudains of St. Clement Deputy J.G. Reed of St. Ouen Witnesses: Senator P.F.C. Ozouf (The Minister for Economic Development) Mr. M. King Deputy G.P. Southern of St. Helier (Chairman): Welcome to this now public hearing of Jersey Telecom Sub Panel. We have now got all members here so we are fully quorate. Welcome, Philip. If I may I would like to start us off by talking about the J.C.R.A. (Jersey Competition Regulatory Authority) and the opening up of the market. I will start with the most recent information I have received in the paper today that the hearing on the number portability has once again been postponed. Would you happen to know any reason for that? Senator P.F.C. Ozouf (The Minister for Economic Development): You have an advantage over me, Chairman, of having read the J.P. (Jersey Evening Post) but I am aware of this and I have to say that I will ask Mike King to comment on this. I am pleased to hear that the hearing is off because of the reasons … I will let Mike explain and then make a comment. Mr. M. King: Yes, I think it is fair to say that the E.D.D. (Economic Development Department) assessment of the situation regarding the hearing on O.N.P. (Operator Number Portability) was that there was room for discussion between particularly Jersey Telecom but also other operators and the regulator to look at alternative ways of resolving the issue of portability in the shortest timeframe, at the lowest cost and in such a way that would deliver to the customers of Jersey a solution which would allow them to have full number portability and free up the market. -

Jersey's Military Landscape

Unlock the Island with Jersey Heritage audio tours that if the French fleet was to leave 1765 with a stone vaulted roof, to St Malo, the news could be flashed replace the original structure (which from lookout ships to Mont Orgueil (via was blown up). It is the oldest defensive Grosnez), to Sark and then Guernsey, fortification in St Ouen’s Bay and, as where the British fleet was stationed. with others, is painted white as a Tests showed that the news could navigation marker. arrive in Guernsey within 15 minutes of the French fleet’s departure! La Rocco Tower F 04 Standing half a mile offshore at St Ouen’s Bay F 02, 03, 04 and 05 the southern end of St Ouen’s Bay In 1779, the Prince of Nassau attempted is La Rocco Tower, the largest of to land with his troops in St Ouen’s Conway’s towers and the last to be Jersey’s spiritual Jersey’s maritime bay but found the Lieutenant built. Like the tower at Archirondel landscape Governor and the Militia waiting for it was built on a tidal islet and has a landscape Immerse Download the FREE audio tour Immerse Download the FREE audio tour him and was easily beaten back. surrounding battery, which helps yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org the history the history However, the attack highlighted the give it a distinctive silhouette. and stories and stories need for more fortifications in the area of Jersey of Jersey and a chain of five towers was built in Portelet H 06 the bay in the 1780s as part of General The tower on the rock in the middle Supported by Supported by Henry Seymour Conway’s plan to of the bay is commonly known as Tourism Development Fund Tourism Development Fund fortify the entire coastline of Jersey. -

In the Circle

ALL THETHE TALK TALK OF THE OF THE IN TERRAIN TERRAIN THE CIRCLE Follow us on This newsletter is also Edition No 3 available on our website September 2016 @ JsyPetanque www.thejpa.co.uk Inter Insular to go ahead in October th The inter-insular match standing fixtures. However applications is September 5 between Jersey and JPA chairman Derek Hart Names should be forwarded Guernsey is now scheduled and the Guernsey Club to … for the weekend of 22nd-23rd captain, John Cuthbertson, [email protected]). October. The annual fixture have agreed to try and play The team of 26 players will was under threat because the event over a weekend. It be selected soon afterwards. Condor’s ferry schedules will of course mean the The JPA has indicated that a made it impossible for the extra expense of an over- small subsidy may be made Jersey squad to travel to night stay and the risk that to support travel and Guernsey and return on the some players won’t be accommodation. The same day. It’s a problem available to take part. The Guernsey Club de Pétanque that other clubs and JPA is now asking members has several indoor terrains, associations have had to who are willing to play to so if the weather is poor the grapple with and in some put their names for ward. Inter Insular could still be cases forced to cancel long- The closing date for played under cover. standing fixtures. However JPA chairman Derek Hart and Home Nations to be INSIDE THE CIRCLE held in Jersey in 2018? THIS QUARTER A great year for the sport in Jersey has surely been capped by the island’s first appearance in the Home Nations Championship.