Read Book Media Ethics at Work 2Nd Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amnesty International Communiqué De Presse

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE Embargo : 23 avril 2007 14h00 TU Des dirigeants, des célébrités et des journalistes appellent les gouvernements à établir un Traité sur le commerce des armes, pour sauver des vies humaines Campagnes Contrôlez les armes : Oxfam International, Amnesty International et le Réseau d’action international sur les armes légères (RAIAL) New York. Trois personnalités féminines soutenant la campagne pour contrôler le commerce international des armes --- la présidente libérienne, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, l’actrice Helen Mirren, titulaire d’un Oscar et l’ancienne présidente irlandaise, Mary Robinson --- ainsi que 20 journalistes célèbres, ont demandé ce lundi 23 avril aux gouvernements d’établir un traité strict sur le commerce des armes, fondé sur le droit international humanitaire et relatif aux droits humains, afin de cesser les transferts d’armes qui entretiennent les conflits et la violence dans le monde. Les gouvernements ont officiellement jusqu’à la fin du mois pour soumettre leurs projets de traité au Secrétaire général des Nations unies. Si ces propositions ne mentionnent pas explicitement l’interdiction des transferts d’armes qui aggravent les conflits, la pauvreté et les atteintes aux droits humains, il existe un risque réel que le traité qui en résultera ne puisse sauver aucune vie, selon les partisans de la campagne. Il est à craindre que des gouvernements sceptiques, comme les États-Unis, tentent d’empêcher l’adoption d’un traité strict. L’actrice Helen Mirren a déclaré : « Du Kenya au Brésil et au Sri Lanka, il y a plus d’armes que jamais, plus faciles et moins chères à obtenir. -

The Archaeologist 59

Winter 2006 Number 59 The ARCHAEOLOGIST This issue: ENVIRONMENTAL ARCHAEOLOGY Submerged forests from early prehistory p10 Views of a Midlands environmental officer p20 Peatlands in peril p25 Institute of Field Archaeologists SHES, University of Reading, Whiteknights The flora of PO Box 227, Reading RG6 6AB Roman roads, tel 0118 378 6446 towns and fax 0118 378 6448 gardens email [email protected] website www.archaeologists.net p32 ONTENTS .%7 -! IN !RCHAEOLOGICAL &IELD 0RACTICE &ULL AND 0ART TIME $EVELOP YOUR CAREER BY TAKING A POSTGRADUATE DEGREE IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL PRACTICE C 4HE 5NIVERSITY OF -ANCHESTER IS LAUNCHING AN EXCITING AND UNIQUE COURSE WHICH SEEKS TO BRIDGE THE GAP BETWEEN THEORY AND PRACTICE )T COMBINES A CRITICAL AND EVALUATIVE APPROACH TO ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION WITH PRACTICAL SKILLS AND TECHNICAL EXPERTISE4AUGHT THROUGH CLASSROOM AND FIELDWORK BASED SESSIONS A PLACEMENT WITHIN THE PROFESSION 1 Contents AND A DISSERTATION ITS EMPHASIS IS UPON FOSTERING A NEW CRITICALLY INFORMED APPROACH TO THE PROFESSION 2 Editorial 4HE 5NIVERSITY OF -ANCHESTER IS AN INTERNATIONALLY RECOGNISED CENTRE FOR SOCIAL ARCHAEOLOGY /UR RESEARCH 3 From the Finds Tray THEMES INCLUDE POWER AND IDENTITY LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AND MONUMENTALITY HERITAGE AND CONTEMPORARY 5 Finishing someone else’s story Michael Heaton, Peter Hinton and Frank Meddens SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PAST RITUAL AND RELIGION THEORY PHILOSOPHY AND PRACTICE OF ARCHAEOLOGY7E ARE A COHERENT 6 IFA and Continuous Professional Development Kate Geary AND FRIENDLY COMMUNITY WITH AN -

Redgrove Papers: Letters

Redgrove Papers: letters Archive Date Sent To Sent By Item Description Ref. No. Noel Peter Answer to Kantaris' letter (page 365) offering back-up from scientific references for where his information came 1 . 01 27/07/1983 Kantaris Redgrove from - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 365. Peter Letter offering some book references in connection with dream, mesmerism, and the Unconscious - this letter is 1 . 01 07/09/1983 John Beer Redgrove pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 380. Letter thanking him for a review in the Times (entitled 'Rhetoric, Vision, and Toes' - Nye reviews Robert Lowell's Robert Peter 'Life Studies', Peter Redgrove's 'The Man Named East', and Gavin Ewart's 'The Young Pobbles Guide To His Toes', 1 . 01 11/05/1985 Nye Redgrove Times, 25th April 1985, p. 11); discusses weather-sensitivity, and mentions John Layard. This letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 373. Extract of a letter to Latham, discussing background work on 'The Black Goddess', making reference to masers, John Peter 1 . 01 16/05/1985 pheromones, and field measurements in a disco - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 229 Latham Redgrove (see 73 . 01 record). John Peter Same as letter on page 229 but with six and a half extra lines showing - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref 1 . 01 16/05/1985 Latham Redgrove No 1, on page 263 (this is actually the complete letter without Redgrove's signature - see 73 . -

The Impact of Internal Migration on Population Redistribution: an International Comparison

The Impact of Internal Migration on Population Redistribution: An International Comparison MARTIN BELL* PHILIP REES MAREK KUPISZEWSKI DOROTA KUPISZEWSKA PHILIPP UEFFING AUDE BERNARD ELIN CHARLES-EDWARDS JOHN STILLWELL *Corresponding Author. School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, The University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia 4072. Phone 61-7-33657087. [email protected] MARTIN BELL is Professor of Geography, Queensland Centre for Population Research, School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, University of Queensland, Australia. PHILIP REES is Professor Emeritus, School of Geography, University of Leeds, UK. MAREK KUPISZEWSKI is Professor, Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization, Polish Academy of Sciences. DOROTA KUPISZEWSKA is an Independent Consultant, Warsaw, Poland, formerly Principal Research Fellow, International Organization for Migration. PHILIPP UEFFING is Research Associate, Queensland Centre for Population Research, School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, University of Queensland, Australia. AUDE BERNARD is Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Queensland Centre for Population Research, School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, University of Queensland, Australia. ELIN CHARLES-EDWARDS is Lecturer in Geography, Queensland Centre for Population Research, School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, University of Queensland, Australia. JOHN STILLWELL is Professor of Migration and Regional Development, School of Geography, University -

6. from Vietnam to Iraq: Negative Trends in Television War Reporting

THE PUBLIC RIGHT TO KNOW 6. From Vietnam to Iraq: Negative trends in television war reporting ABSTRACT In 1876, an American newspaperman with the US 7th Cavalry, Mark Kellogg, declared: ‘I go with Custer, and will be at the death.’1 This overtly heroic pronouncement embodies what many still want to believe is the greatest role in journalism: to go up to the fight, to be with ‘the boys’, to expose yourself to risk, to get the story and the blood-soaked images, to vividly describe a world of strength and weakness, of courage under fire, of victory and defeat—and, quite possibly, to die. So culturally embedded has this idea become that it raises hopes among thousands of journalism students worldwide that they too might become that holiest of entities in the media pantheon, the television war correspondent. They may find they have left it too late. Accompanied by evolutionary technologies and breathtaking media change, TV war reporting has shifted from an independent style of filmed reportage to live pieces-to-camera from reporters who have little or nothing to say. In this article, I explore how this has come about; offer some views about the resulting negative impact on practitioners and the public; and explain why, in my opinion, our ‘right to know’ about warfare has been seriously eroded as a result. Keywords: conflict reporting, embedded, television war reporting, war correspondents TONY MANIATY Australian Centre for Independent Journalism N 22nd December 1961, the first American serviceman was killed in Saigon. By April 1969 a staggering 543,000 US troops occupied OSouth Vietnam, with calls from field commanders for even more. -

Community Guide 1

Images of War Celebrations of PeaceThe Photographs and Collage Art of Dan Eldon A Community Guide to accompany the traveling exhibit “Once one has been to these challenging, terrible places, they’re always strangely drawn back because there’s nothing that can compare to seeing the raw reality of the basic human need for survival. It disgusts and inspires.” –Dan Eldon Purpose of this Guide The following activities and discussion questions are provided to help members of your community to better understand and enjoy the exhibit Images of War. Celebrations of Peace: The Photographs and Collage Art of Dan Eldon. We have put the guide on the Internet in hopes of making it available to the widest audience possible; however, a paper version will also travel with the exhibit and may be copied. Appropriate Audience The guide has been created by a team of college and high school educators and is intended for a broad audience, including school-aged students (middle school through college level), youth groups (e.g., church groups, older scout groups), and adults (e.g., members of book clubs, art groups, and retirement educational groups). Our hope is that the activities and discussion questions, which are purposely broad, can be easily adapted for various audiences and settings. How to Use This Guide The Guide is broken into five parts: 1. About Dan Eldon – a brief overview of his life 2. The Exhibit – Activities and Discussion 3. The Book – Dan Eldon: The Art of Life 4. The Film – Dying to Tell the Story 5. Resources The questions and activities in this guide are meant to elucidate your experience of each of these three things. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. A Public Theology for Peace Photography: A Critical Analysis of the Roles of Photojournalism in Peacebuilding, with the Special Reference to the Gwangju Uprising in South Korea Sangduk Kim i ii I, Sangduk Kim, attests that this thesis has been composed by me, and that the work is my own, and that the work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Sangduk Kim iii iv Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Jolyon Mitchell for his continuous support of my PhD studies and related research, for his kindness, encouragement, and immense knowledge. His guidance helped me throughout the time of research and writing of this thesis. I could not have imagined having a better supervisor and mentor for my PhD study. -

Vertical File

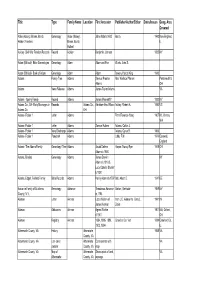

Title Type Family Name Location First Ancestor Publisher/Author/Editor Dates/Issues Geog. Area Covered Abbe (Abbey), Brown, Burch, Genealogy Abbe (Abbey), John Abbe b.1613 Burch 1943 New England, Hulbert Families Brown, Burch, IL Hulbert Ackley- Civil War Pension Records Record Ackley Benjamin Johnson 1832 NY Adam (Biblical)- Bible Genealogies Genealogy Adam Adam and Eve Wurts, John S. Adam (Biblical)- Book of Adam Genealogy Adam Adam Bowen, Harold King 1943 Adams Family Tree Adams Samuel Preston Mrs. Wallace Phorsm Portsmouth & Adams OH Adams News Release Adams James Taylor Adams VA Adams - Spring Family Record Adams James Wamorth? 1832 NY Adams Co., OH- Early Marriages in Records Adams Co., Abraham thru Wilson Ackley, Robert A. 1982 US Adams Co. OH Adams- Folder 1 Letter Adams From Florence Hoag 1907 Mt. Vernon, WA Adams- Folder 1 Letter Adams Samuel Adams Adams, Calvin J. Adams- Folder 1 Navy Discharge Adams Adams, Cyrus B. 1866 Adams- Folder 1 Pamphlet Adams Lobb, F.M. 1979 Cornwall, England Adams- The Adams Family Genealogy/ Tree Adams Jacob Delmar Harper, Nancy Eyer 1978 OH Adams b.1858 Adams, Broyles Genealogy Adams James Darwin KY Adams b.1818 & Lucy Ophelia Snyder b.1820 Adams, Edgell, Twiford Family Bible Records Adams Henry Adams b.1797 Bell, Albert D. 1947 DE Adriance Family of Dutchess Genealogy Adriance Theodorus Adriance Barber, Gertrude 1959 NY County, N.Y. m.1783 Aikman Letter Aikman Lists children of from L.C. Aikman to Cora L. 1941 IN James Aikman Davis Aikman Obituaries Aikman Agnes Ritchie 1901 MA, Oxford, d.1901 OH Aikman Registry Aikman 1884, 1895, 1896, Crawford Co. -

The Story of BBC News in Northern Ireland

chronicle The Story of BBC News in Northern Ireland GEN72252 BBC BOOKLET ST8 FINAL.indd 2 19/02/2009 19:54 GEN72252 BBC BOOKLET ST8 FINAL.indd 2 19/02/2009 19:54 Issues, Dilemmas The existence of an online accompaniment and Opportunities to this initiative is an indication of how much has changed in recent decades. Our platforms “The future is not just an extension of the past: for communication are now vastly different something new enters in.” and significantly more diverse. We have made the transition from black and white to colour (John Updike: Due Considerations) pictures and from mute film to high definition digital images. Limited local programming on The appointment of the BBC’s first television the Home Service has been succeeded by BBC journalist at Broadcasting House in Belfast was Radio Ulster and Radio Foyle and Ceefax is a significant development in 1955. In those today complemented by a range of interactive days, Northern Ireland was seen as something television services. Satellite connections, mobile of a provincial backwater where not very much telephony and the internet have become happened. Within a relatively short period almost commonplace and citizen journalism (in of time that image and everyday life were to all its different forms) is an increasing part of change in ways which would have far-reaching the BBC’s output. social, political and editorial consequences. Chronicle highlights some of the issues and Throughout the Troubles the BBC’s Belfast dilemmas which have shaped BBC journalism newsroom was a crowded, and sometimes and the audience it serves. -

PDF File of Chapter 1

Ethics and journalism? 1 A reporter is `a man without virtue who writes lies . for his pro®t.' Dr Samuel Johnson THE REPORTING BESTIARY: WATCHDOGS, VULTURES AND GADFLYS In polls conducted in 1993 estate agents received the lowest rating in British public esteem; journalists were just above them. And yet the lure of a career in the media is stronger than ever. Reporters repel and attract; they are the twenty- ®rst century equivalent of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the `hack' for whom, in the words of foreign correspondent, Nicholas Tomalin, the only necessary quali- ®cations are `a plausible manner, rat-like cunning and a little literary ability.' Little trusted, little loved (but often secretly admired), the reporter is seen as the cynical, ruthless ®gure parodied in the Channel 4 series Drop the Dead Donkey (1990±98) and ®lms such as Broadcast News (1987) and Network (1976). Described by the satirical magazine, Private Eye, and the Royal Family as `the reptiles', compared to jackals and vultures feeding on human carrion, this image of the journalist reached its apotheosis at the time of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997. The presence and behaviour of the paparazzi at the scene of the accident and Earl Spencer's public accusation that `editors have blood on their hands ± I always believed the press would kill her in the end,' was a low-water mark for British journalism. Earlier that same year, the white-suited Martin Bell, a former BBC corre- spondent, won election to Parliament as the unof®cial, anti-corruption candidate against the discredited Conservative contender, Neil Hamilton. -

Penguin Classics

PENGUIN CLASSICS A Complete Annotated Listing www.penguinclassics.com PUBLISHER’S NOTE For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world, providing readers with a library of the best works from around the world, throughout history, and across genres and disciplines. We focus on bringing together the best of the past and the future, using cutting-edge design and production as well as embracing the digital age to create unforgettable editions of treasured literature. Penguin Classics is timeless and trend-setting. Whether you love our signature black- spine series, our Penguin Classics Deluxe Editions, or our eBooks, we bring the writer to the reader in every format available. With this catalog—which provides complete, annotated descriptions of all books currently in our Classics series, as well as those in the Pelican Shakespeare series—we celebrate our entire list and the illustrious history behind it and continue to uphold our established standards of excellence with exciting new releases. From acclaimed new translations of Herodotus and the I Ching to the existential horrors of contemporary master Thomas Ligotti, from a trove of rediscovered fairytales translated for the first time in The Turnip Princess to the ethically ambiguous military exploits of Jean Lartéguy’s The Centurions, there are classics here to educate, provoke, entertain, and enlighten readers of all interests and inclinations. We hope this catalog will inspire you to pick up that book you’ve always been meaning to read, or one you may not have heard of before. To receive more information about Penguin Classics or to sign up for a newsletter, please visit our Classics Web site at www.penguinclassics.com. -

This Book Is Available from the British Library

The War Correspondent The War Correspondent Fully updated second edition Greg McLaughlin First published 2002 Fully updated second edition first published 2016 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Greg McLaughlin 2002, 2016 The right of Greg McLaughlin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3319 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3318 2 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7837 1758 3 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1760 6 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1759 0 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the European Union and United States of America To Sue with love Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations x 1 Introduction 1 PART I: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 2 The War Correspondent: Risk, Motivation and Tradition 9 3 Journalism, Objectivity and War 33 4 From Luckless Tribe to Wireless Tribe: The Impact of Media Technologies on War Reporting 63 PART II: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT AND THE MILITARY 5 Getting to Know Each Other: From Crimea to Vietnam 93 6 Learning and Forgetting: From the Falklands to the