Community Guide 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amnesty International Communiqué De Presse

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE Embargo : 23 avril 2007 14h00 TU Des dirigeants, des célébrités et des journalistes appellent les gouvernements à établir un Traité sur le commerce des armes, pour sauver des vies humaines Campagnes Contrôlez les armes : Oxfam International, Amnesty International et le Réseau d’action international sur les armes légères (RAIAL) New York. Trois personnalités féminines soutenant la campagne pour contrôler le commerce international des armes --- la présidente libérienne, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, l’actrice Helen Mirren, titulaire d’un Oscar et l’ancienne présidente irlandaise, Mary Robinson --- ainsi que 20 journalistes célèbres, ont demandé ce lundi 23 avril aux gouvernements d’établir un traité strict sur le commerce des armes, fondé sur le droit international humanitaire et relatif aux droits humains, afin de cesser les transferts d’armes qui entretiennent les conflits et la violence dans le monde. Les gouvernements ont officiellement jusqu’à la fin du mois pour soumettre leurs projets de traité au Secrétaire général des Nations unies. Si ces propositions ne mentionnent pas explicitement l’interdiction des transferts d’armes qui aggravent les conflits, la pauvreté et les atteintes aux droits humains, il existe un risque réel que le traité qui en résultera ne puisse sauver aucune vie, selon les partisans de la campagne. Il est à craindre que des gouvernements sceptiques, comme les États-Unis, tentent d’empêcher l’adoption d’un traité strict. L’actrice Helen Mirren a déclaré : « Du Kenya au Brésil et au Sri Lanka, il y a plus d’armes que jamais, plus faciles et moins chères à obtenir. -

The Archaeologist 59

Winter 2006 Number 59 The ARCHAEOLOGIST This issue: ENVIRONMENTAL ARCHAEOLOGY Submerged forests from early prehistory p10 Views of a Midlands environmental officer p20 Peatlands in peril p25 Institute of Field Archaeologists SHES, University of Reading, Whiteknights The flora of PO Box 227, Reading RG6 6AB Roman roads, tel 0118 378 6446 towns and fax 0118 378 6448 gardens email [email protected] website www.archaeologists.net p32 ONTENTS .%7 -! IN !RCHAEOLOGICAL &IELD 0RACTICE &ULL AND 0ART TIME $EVELOP YOUR CAREER BY TAKING A POSTGRADUATE DEGREE IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL PRACTICE C 4HE 5NIVERSITY OF -ANCHESTER IS LAUNCHING AN EXCITING AND UNIQUE COURSE WHICH SEEKS TO BRIDGE THE GAP BETWEEN THEORY AND PRACTICE )T COMBINES A CRITICAL AND EVALUATIVE APPROACH TO ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION WITH PRACTICAL SKILLS AND TECHNICAL EXPERTISE4AUGHT THROUGH CLASSROOM AND FIELDWORK BASED SESSIONS A PLACEMENT WITHIN THE PROFESSION 1 Contents AND A DISSERTATION ITS EMPHASIS IS UPON FOSTERING A NEW CRITICALLY INFORMED APPROACH TO THE PROFESSION 2 Editorial 4HE 5NIVERSITY OF -ANCHESTER IS AN INTERNATIONALLY RECOGNISED CENTRE FOR SOCIAL ARCHAEOLOGY /UR RESEARCH 3 From the Finds Tray THEMES INCLUDE POWER AND IDENTITY LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AND MONUMENTALITY HERITAGE AND CONTEMPORARY 5 Finishing someone else’s story Michael Heaton, Peter Hinton and Frank Meddens SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PAST RITUAL AND RELIGION THEORY PHILOSOPHY AND PRACTICE OF ARCHAEOLOGY7E ARE A COHERENT 6 IFA and Continuous Professional Development Kate Geary AND FRIENDLY COMMUNITY WITH AN -

Redgrove Papers: Letters

Redgrove Papers: letters Archive Date Sent To Sent By Item Description Ref. No. Noel Peter Answer to Kantaris' letter (page 365) offering back-up from scientific references for where his information came 1 . 01 27/07/1983 Kantaris Redgrove from - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 365. Peter Letter offering some book references in connection with dream, mesmerism, and the Unconscious - this letter is 1 . 01 07/09/1983 John Beer Redgrove pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 380. Letter thanking him for a review in the Times (entitled 'Rhetoric, Vision, and Toes' - Nye reviews Robert Lowell's Robert Peter 'Life Studies', Peter Redgrove's 'The Man Named East', and Gavin Ewart's 'The Young Pobbles Guide To His Toes', 1 . 01 11/05/1985 Nye Redgrove Times, 25th April 1985, p. 11); discusses weather-sensitivity, and mentions John Layard. This letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 373. Extract of a letter to Latham, discussing background work on 'The Black Goddess', making reference to masers, John Peter 1 . 01 16/05/1985 pheromones, and field measurements in a disco - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 229 Latham Redgrove (see 73 . 01 record). John Peter Same as letter on page 229 but with six and a half extra lines showing - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref 1 . 01 16/05/1985 Latham Redgrove No 1, on page 263 (this is actually the complete letter without Redgrove's signature - see 73 . -

Telling Stories to a Different Beat: Photojournalism As a “Way of Life”

Bond University DOCTORAL THESIS Telling stories to a different beat: Photojournalism as a “Way of Life” Busst, Naomi Award date: 2012 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Telling stories to a different beat: Photojournalism as a “Way of Life” Naomi Verity Busst, BPhoto, MJ A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Media and Communication Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Bond University February 2012 Abstract This thesis presents a grounded theory of how photojournalism is a way of life. Some photojournalists dedicate themselves to telling other people's stories, documenting history and finding alternative ways to disseminate their work to audiences. Many self-fund their projects, not just for the love of the tradition, but also because they feel a sense of responsibility to tell stories that are at times outside the mainstream media’s focus. Some do this through necessity. While most photojournalism research has focused on photographers who are employed by media organisations, little, if any, has been undertaken concerning photojournalists who are freelancers. -

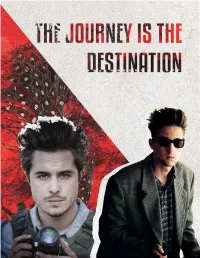

JTD EPK FINAL 8.2016.Pdf

2 and O’Reilly, the journalists who be- come Dan’s guides to the world of war correspondence, Ella Purnell (Tarzan, Never Let Me Go, Maleficent), as Dan’s Synopsis sister Amy and Maria Bello (Prisoners, The Journey is the Destination is in- A History of Violence), as his mother spired by the true story of Dan Eldon, Kathy. a charismatic young activist, artist, photographer and adventurer. By As a young man of American and the age of 22, Dan had traveled to 42 British parentage growing up in Afri- countries, created a series of fine art ca, Dan Eldon always had an instinct journals that would become interna- for helping others. At the age of 19, tional best sellers, worked in refugee aware of the plight of refugees in camps, opened a business, became Malawi, he launched Student Trans- the youngest staff photojournalist at port Aid, and he and his friends Reuters, fallen in love and accumulat- drove across five African countries ed more life experience than most in a to hand-deliver the money they’d lifetime. raised to a refugee camp in the mid- dle of a war zone. Along the way Visually stunning and wildly inspiring, they witnessed examples of sublime The Journey is the Destination follows beauty and extreme hardship. The a young man’s tumultuous coming of trip changed the lives of everyone age, his exploration of love and his involved. struggle to create positive change in an increasingly violent and dangerous world. Dan was a unique person who woke up every day with the drive to make the world a little better before he went to sleep. -

“The Journey Is the Destination: Safari with Dan Eldon”

Objects of Art LA Presents a Special Exhibition “The Journey is the Destination: Safari with Dan Eldon” Limited Edition Prints from the Journals of Dan Eldon, Including Many Never Before on Offer October 6-8, 2017 September, 2017-- This October, Objects of Art LA will debut at The Reef in Los Angeles. One of the highlights is a special exhibit “The Journey is the Destination: Safari with Dan Eldon,” featuring over 25 limited edition prints from the journals of the artist, many of which were featured in the best-selling book of the same name published by Chronicle Books. Much of the work has never been on offer before and this will be the first time any of the prints will have been exhibited for sale on the West Coast. Every piece has a direct reference to Eldon’s safaris, and Objects of Art LA will be the only place to view several of his actual journals, which will also be part of the exhibition. Eldon's art is in numerous prestigious private collections, including those of Diana Rockefeller, Madonna, Julia Roberts, Christiane Amanpour and Rosie O'Donnell, among many others. There will also be two showings of the new award-winning feature film launched at the Toronto Film Festival, The Journey is the Destination, starring Maria Bello and Ben Schnetzer, which tells the story of how Dan Eldon, the artist, explorer, and Reuters photojournalist, led a group of unlikely teens on a rollicking safari across Africa to deliver aid to a refugee camp in Malawi in 1990. The film then follows Dan as he finds himself covering a famine and spiraling civil war in Somalia as Reuters’ youngest photojournalist. -

Hamish Johnson Mr. Patterson-Gram History 12 2-3 24 November 2018

Johnson 1 Hamish Johnson Mr. Patterson-Gram History 12 2-3 24 November 2018 Effect of Conflict Photojournalism on Government Actions and Censorship Throughout the twentieth century, there has been a rapid increase of information available to the general public. From print and radio to television and even internet, the “average joe” now has access to live information from around the world (whether it is accurate or not is another question entirely). This huge societal shift is in part due to the rise of multimedia equipment and journalism having played a large role in shaping not only our modern governments but our expectations from the world around us. Being able to condense the raw elements of emotion, storytelling, perspective, and history into a single photograph gives photojournalism its unique appeal to the public. If a picture is worth a thousand words, why not use it? The essential trait of photojournalism, whether it be for social change, humanitarian crisis, wars both local and afar, or daily news, boils down to “bearing witness.”1 The power of photojournalism to allow one to see the outside world is unparalleled in terms of efficiency. However, this convenience is not always a virtue for governments and organizations that wish to limit knowledge or access to the general public. As the ease of use of media technologies has increased, governments, especially in war, have needed to adapt to new forms of censorship and secrecy to protect reputation and control the public. For most of human history, conflicts have been directly recounted to the public by the victors and typically through the government. -

The Impact of Internal Migration on Population Redistribution: an International Comparison

The Impact of Internal Migration on Population Redistribution: An International Comparison MARTIN BELL* PHILIP REES MAREK KUPISZEWSKI DOROTA KUPISZEWSKA PHILIPP UEFFING AUDE BERNARD ELIN CHARLES-EDWARDS JOHN STILLWELL *Corresponding Author. School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, The University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia 4072. Phone 61-7-33657087. [email protected] MARTIN BELL is Professor of Geography, Queensland Centre for Population Research, School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, University of Queensland, Australia. PHILIP REES is Professor Emeritus, School of Geography, University of Leeds, UK. MAREK KUPISZEWSKI is Professor, Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization, Polish Academy of Sciences. DOROTA KUPISZEWSKA is an Independent Consultant, Warsaw, Poland, formerly Principal Research Fellow, International Organization for Migration. PHILIPP UEFFING is Research Associate, Queensland Centre for Population Research, School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, University of Queensland, Australia. AUDE BERNARD is Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Queensland Centre for Population Research, School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, University of Queensland, Australia. ELIN CHARLES-EDWARDS is Lecturer in Geography, Queensland Centre for Population Research, School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, University of Queensland, Australia. JOHN STILLWELL is Professor of Migration and Regional Development, School of Geography, University -

Dan Eldon: the Art of Life Jennifer New Chronicle Books, 2001

Bibliography The Art of Exploration The Journey Is the Destination Kathy Eldon EXTRAORDINARY EXPLORERS AND CREATORS INSPIRE US ALL TO REACH OUR OWN POTENTIAL Chronicle Books, 1997 Dan Eldon: The Art of Life Jennifer New Chronicle Books, 2001 Dying to Tell the Story Amy Eldon TBS The Art of Life Charles Tsai CNN Deadly Destiny: National Geographic on Assignment Patti Kim Dan Eldon National Geographic Dan Eldon was born in London in 1970 to an American Websites mother and a British father. Along with his younger sis- www.daneldon.org www.creativevisions.org ter, Amy, Dan and his family moved to Kenya in east Africa in 1977. Kenya remained Dan's home for the rest Related Books of his life, and though he traveled often - visiting more Drawing from Life: The Journal as Art than 40 countries in 22 years - he always considered Jennifer New Africa home. Princeton Architectural Press 2005 Dan's father led the east Africa division of a European computer company and his mother Kathy, an Iowa Me Against My Brother: At War in Somalia, Sudan, and Rwanda Scott Peterson native, was a freelance journalist. Kenya was a popular Routledge, 2000 destination in the late 1970s and 1980s; it was more politically stable and economically secure than most The Zanzibar Chest: A Story of Life, Love, and Death in Foreign Lands African nations, and the bountiful wildlife and perfect cli- Aidan Hartley mate made it all the more appealing. Dan and Amy grew Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003 up with a constant stream of interesting visitors at their dinner table. -

6. from Vietnam to Iraq: Negative Trends in Television War Reporting

THE PUBLIC RIGHT TO KNOW 6. From Vietnam to Iraq: Negative trends in television war reporting ABSTRACT In 1876, an American newspaperman with the US 7th Cavalry, Mark Kellogg, declared: ‘I go with Custer, and will be at the death.’1 This overtly heroic pronouncement embodies what many still want to believe is the greatest role in journalism: to go up to the fight, to be with ‘the boys’, to expose yourself to risk, to get the story and the blood-soaked images, to vividly describe a world of strength and weakness, of courage under fire, of victory and defeat—and, quite possibly, to die. So culturally embedded has this idea become that it raises hopes among thousands of journalism students worldwide that they too might become that holiest of entities in the media pantheon, the television war correspondent. They may find they have left it too late. Accompanied by evolutionary technologies and breathtaking media change, TV war reporting has shifted from an independent style of filmed reportage to live pieces-to-camera from reporters who have little or nothing to say. In this article, I explore how this has come about; offer some views about the resulting negative impact on practitioners and the public; and explain why, in my opinion, our ‘right to know’ about warfare has been seriously eroded as a result. Keywords: conflict reporting, embedded, television war reporting, war correspondents TONY MANIATY Australian Centre for Independent Journalism N 22nd December 1961, the first American serviceman was killed in Saigon. By April 1969 a staggering 543,000 US troops occupied OSouth Vietnam, with calls from field commanders for even more. -

Shaped by War: Photographs by Don Mccullin 7 October 2011 – 15 April 2012

Shaped by War: Photographs by Don McCullin 7 October 2011 – 15 April 2012 Shaped by War is the largest ever UK exhibition about the life and work of one of the world’s most acclaimed photographers Don McCullin. The exhibition, which features around 250 photographs, contact sheets, objects, magazines and personal memorabilia, opens in an updated form at IWM London this October following a highly successful run at IWM North last year. Don McCullin has photographed war for more than 50 years and many of his iconic black and white images have come to shape our awareness of modern conflict and its consequences. Shaped by War brings together McCullin’s frontline work from conflicts all over the world including the confrontation between East and West Berlin, Vietnam and Cambodia, the conflicts of the Middle East and the intense human suffering in Biafra and Bangladesh. These are displayed alongside McCullin’s photographs of more recent conflicts such as the Gulf War and the 2003 Invasion of Iraq. A number of significant portraits, which have been rarely seen in public, have also been released by McCullin especially for the exhibition at IWM London. These include several haunting images of anonymous victims of wars around the world plus two portraits of Lance Corporal Johnson Beharry whose series of brave actions in Iraq in 2004 saw him awarded a Victoria Cross. The stunning principal photograph captures the tattoo of a Victoria Cross which covers Beharry’s back, and was the first digital photograph by McCullin to ever go on public display. It was commissioned by IWM in 2010 for the opening of its Extraordinary Heroes exhibition in The Lord Ashcroft Gallery at IWM London. -

1 the WARS of DON MCCULLIN Michel Guerrin & Alain Frachon

THE WARS OF DON MCCULLIN Michel Guerrin & Alain Frachon, "Les guerres de Don McCullin" Le Monde, 15 -19 August 2018, various pages. A suite of articles written for the summer edition of Le Monde by Michel Guerrin and Alain Frachon, journalists with Le Monde. DON MCCULLIN, PHOTOGRAPHER 1 | 6 From his poor childhood to his landscapes, passing through Vietnam, for this British master of photography, all is conflict. Le Monde went to visit him and retraces the journey which led him from the gangs of London to his fame. Batcombe, Somerset (UK) - Special correspondents The photographer closes the door of his darkroom – the room of his “ghosts.” It is from there which they emerge, the “ghosts,” from a prefabricated cabin behind the house. They come from four immaculate white bins – developer, bath, fiXer and wash. Beside these are the enlargers, and on shelves there are reams of paper, all of which float in a putrid smell of potassium iodide. “You know that almost everything happens here, in this darkroom,” says Donald McCullin: siXty years of photography of which eighteen were devoted to war. “Soon, I’m going to get rid of all of it. I am at the end of my journey.” It is hard to believe. This man risked a thousand deaths in wars. In 2016 again, he was in Iraq. He was injured in Cambodia, beaten up in prisons in Idi Amin Dada. A price was put on his head in Lebanon. In PalmyrA, Syria, only two years ago, his lung was pierced from a fall. “I paid a good price,” he says, but in half a century of reportage in the form of ‘eXtreme journalism’, McCullin was never K.O.