German Actors PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 7, Issue 2, July 2021 Introduction: New Researchers and the Bright Future of Military History

www.bjmh.org.uk British Journal for Military History Volume 7, Issue 2, July 2021 Cover picture: Royal Navy destroyers visiting Derry, Northern Ireland, 11 June 1933. Photo © Imperial War Museum, HU 111339 www.bjmh.org.uk BRITISH JOURNAL FOR MILITARY HISTORY EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD The Editorial Team gratefully acknowledges the support of the British Journal for Military History’s Editorial Advisory Board the membership of which is as follows: Chair: Prof Alexander Watson (Goldsmiths, University of London, UK) Dr Laura Aguiar (Public Record Office of Northern Ireland / Nerve Centre, UK) Dr Andrew Ayton (Keele University, UK) Prof Tarak Barkawi (London School of Economics, UK) Prof Ian Beckett (University of Kent, UK) Dr Huw Bennett (University of Cardiff, UK) Prof Martyn Bennett (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Dr Matthew Bennett (University of Winchester, UK) Prof Brian Bond (King’s College London, UK) Dr Timothy Bowman (University of Kent, UK; Member BCMH, UK) Ian Brewer (Treasurer, BCMH, UK) Dr Ambrogio Caiani (University of Kent, UK) Prof Antoine Capet (University of Rouen, France) Dr Erica Charters (University of Oxford, UK) Sqn Ldr (Ret) Rana TS Chhina (United Service Institution of India, India) Dr Gemma Clark (University of Exeter, UK) Dr Marie Coleman (Queens University Belfast, UK) Prof Mark Connelly (University of Kent, UK) Seb Cox (Air Historical Branch, UK) Dr Selena Daly (Royal Holloway, University of London, UK) Dr Susan Edgington (Queen Mary University of London, UK) Prof Catharine Edwards (Birkbeck, University of London, -

M. Strohn: the German Army and the Defence of the Reich

Matthias Strohn. The German Army and the Defence of the Reich: Military Doctrine and the Conduct of the Defensive Battle 1918–1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 292 S. ISBN 978-0-521-19199-9. Reviewed by Brendan Murphy Published on H-Soz-u-Kult (November, 2013) This book, a revised version of Matthias political isolation to cooperation in military mat‐ Strohn’s Oxford D.Phil dissertation is a reap‐ ters. These shifts were necessary decisions, as for praisal of German military thought between the ‘the Reichswehr and the Wehrmacht in the early World Wars. Its primary subjects are political and stages of its existence, the core business was to military elites, their debates over the structure find out how the Fatherland could be defended and purpose of the Weimar military, the events against superior enemies’ (p. 3). that shaped or punctuated those debates, and the This shift from offensive to defensive put the official documents generated at the highest levels. Army’s structural subordination to the govern‐ All of the personalities, institutions and schools of ment into practice, and shocked its intellectual thought involved had to deal with a foundational culture into a keener appreciation of facts. To‐ truth: that any likely adversary could destroy ward this end, the author tracks a long and wind‐ their Army and occupy key regions of the country ing road toward the genesis of ‘Heeresdien‐ in short order, so the military’s tradition role was stvorschrfift 300. Truppenführung’, written by doomed to failure. Ludwig Beck and published in two parts in 1933 The author lays out two problems to be ad‐ and 1934, a document which is widely regarded to dressed. -

Day Fighters in Defence of the Reich : a War Diary, 1942-45 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DAY FIGHTERS IN DEFENCE OF THE REICH : A WAR DIARY, 1942-45 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Donald L. Caldwell | 424 pages | 29 Feb 2012 | Pen & Sword Books Ltd | 9781848325258 | English | Barnsley, United Kingdom Day Fighters in Defence of the Reich : A War Diary, 1942-45 PDF Book Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. A summary of every 8th and 15th US Army Air Force strategic mission over this area in which the Luftwaffe was encountered. You must have JavaScript enabled in your browser to utilize the functionality of this website. The American Provisional Tank Group had been in the Philippines only three weeks when the Japanese attacked the islands hours after the raid on Pearl Harbor. World history: from c -. Captured at Kut, Prisoner of the Turks: The. Loses a star for its format, the 'log entries' get a little dry but the pictures and information is excellent. New copy picked straight from printer's box. Add to Basket. Check XE. Following separation from the Navy, Caldwell returned to Texas to begin a career in the chemical industry. Anthony Barne started his diary in August as a young, recently married captain in His first book, JG Top Guns of the Luftwaffe, has been followed by four others on the Luftwaffe: all have won critical and popular acclaim for their accuracy, objectivity, and readability. W J Mott rated it it was amazing Dec 17, Available in the following formats: Hardback ePub Kindle. The previous volume in this series, The Luftwaffe over Germany: Defence of the Reich is an award-winning narrative history published by Greenhill Books. -

Fleet Air Arm Record Breakers & Medal

BETTER….FASTER…… FURTHER….BRAVER….. Fleet Air Arm Record Breakers & Medal Winners Quiz The Fleet Air Arm has achieved many technological firsts and broken many records in a century of Naval Aviation. The bravery of Fleet Air Arm aircrews has won them many medals, including four Victoria Crosses. Complete this trail to find out about the record breakers and Victoria Crosses on display in the Museum. Recordbreakersmarch2013Ed1 ©FleetAirArmMuseum2013 Hall 1 RECORD BREAKER Early aircra made by the Short brothers were great record breakers. In June 1910, the S38, an aircra very similar to the S27 on display, achieved the record for the highest flight. It flew at 1180 feet: not very high by today’s standards but breath-taking then. The S27 was the first aeroplane to fly from a moving ship and it won an endurance record in 1912 when it flew 4 hours non-stop. RECORD BREAKER This biplane was the first type of aircra to land on a moving ship. Tragically, its record breaking pilot crashed and died the third me he aempted this dangerous manoeuvre. Name the aircra: _________SOPWITH PUP___ Name the pilot: __________EDWIN DUNNING____ RECORD BREAKER - FACT FILE The Lynx helicopter holds the official helicopter world speed record. The record breaking flight of 249.1MpH (400.8 KpH) took place not far from this Museum, in 1986. Only recently have other helicopters begun to challenge this outstanding achievement. MEDAL WINNER Look for the display near the Short 184 This WW1 fearless fighter pilot won his Victoria Cross when he single-handedly destroyed a German Zeppelin returning from The Victoria Cross its mission to bomb English cies. -

Semaphore Circular No 700 the Beating Heart of the RNA JUNE 2020

The Semaphore Circular No 700 The Beating Heart of the RNA JUNE 2020 Lots of ‘Gold Brass’ was on display commemorating VE75 Day in Broad Street Old Portsmouth. National President Vice Admiral John McAnally is joined by Vice Admiral Jerry Kidd, the Fleet Commander, Honorary Capt Robin Knox Johnston and General Secretary, Bill Oliphant. Admiral John and Captain Bill later paid their respects at the Naval Memorial laying a wreath Shipmates Please Stay Safe If you need assistance call the RNA Helpline on 07542 680082 This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec 1 Daily Orders (follow each link) Orders [follow each link] 1. NHS and Ventilator Appeal 2. Respectful Joke 3. BRNC Covid Passing out Parade 4. Guess the Establishment 5. Why I Joined The RNA 6. RNA Clothing and Slops 7. RNA Christmas card Competition 8. Quickie Joke 9. Dunkirk 80th Anniversary 10. The Unusual Photo 11. A Thousand Good Deeds 12. VC Series - Lt Cdr Eugen Esmonde VC DSO MiD RN 13. Cenotaph Parade 2020 14. RN Veterans Photo Competition 15. Answer to Guess the Establishment 16. Joke Time IT History Lesson 17. Zoom Stuff 18. And finally Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman -

View of the British Way in Warfare, by Captain B

“The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Katie Lynn Brown August 2011 © 2011 Katie Lynn Brown. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled “The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 by KATIE LYNN BROWN has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Peter John Brobst Associate Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT BROWN, KATIE LYNN, M.A., August 2011, History “The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 Director of Thesis: Peter John Brobst The historiography of British grand strategy in the interwar years overlooks the importance air power had in determining Britain’s interwar strategy. Rather than acknowledging the newly developed third dimension of warfare, most historians attempt to place air power in the traditional debate between a Continental commitment and a strong navy. By examining the development of the Royal Air Force in the interwar years, this thesis will show that air power was extremely influential in developing Britain’s grand strategy. Moreover, this thesis will study the Royal Air Force’s reliance on strategic bombing to consider any legal or moral issues. Finally, this thesis will explore British air defenses in the 1930s as well as the first major air battle in World War II, the Battle of Britain, to see if the Royal Air Force’s almost uncompromising faith in strategic bombing was warranted. -

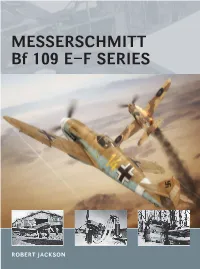

Messerschmitt Bf 109 E–F Series

MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109 E–F SERIES ROBERT JACKSON 19/06/2015 12:23 Key MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109E-3 1. Three-blade VDM variable pitch propeller G 2. Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine, 12-cylinder inverted-Vee, 1,150hp 3. Exhaust 4. Engine mounting frame 5. Outwards-retracting main undercarriage ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND ILLUSTRATOR 6. Two 20mm cannon, one in each wing 7. Automatic leading edge slats ROBERT JACKSON is a full-time writer and lecturer, mainly on 8. Wing structure: All metal, single main spar, stressed skin covering aerospace and defense issues, and was the defense correspondent 9. Split flaps for North of England Newspapers. He is the author of more than 10. All-metal strut-braced tail unit 60 books on aviation and military subjects, including operational 11. All-metal monocoque fuselage histories on famous aircraft such as the Mustang, Spitfire and 12. Radio mast Canberra. A former pilot and navigation instructor, he was a 13. 8mm pilot armour plating squadron leader in the RAF Volunteer Reserve. 14. Cockpit canopy hinged to open to starboard 11 15. Staggered pair of 7.92mm MG17 machine guns firing through 12 propeller ADAM TOOBY is an internationally renowned digital aviation artist and illustrator. His work can be found in publications worldwide and as box art for model aircraft kits. He also runs a successful 14 13 illustration studio and aviation prints business 15 10 1 9 8 4 2 3 6 7 5 AVG_23 Inner.v2.indd 1 22/06/2015 09:47 AIR VANGUARD 23 MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109 E–F SERIES ROBERT JACKSON AVG_23_Messerschmitt_Bf_109.layout.v11.indd 1 23/06/2015 09:54 This electronic edition published 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Osprey Publishing, PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA E-mail: [email protected] Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc © 2015 Osprey Publishing Ltd. -

NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL (NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946 Page numbers in braces refer to IMT, judgment of 1 October 1946, in The Trial of German Major War Criminals. Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg, Germany , Part 22 (22nd August ,1946 to 1st October, 1946) 1 {iii} THE INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL IN SESSOIN AT NUREMBERG, GERMANY Before: THE RT. HON. SIR GEOFFREY LAWRENCE (member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) President THE HON. SIR WILLIAM NORMAN BIRKETT (alternate member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) MR. FRANCIS BIDDLE (member for the United States of America) JUDGE JOHN J. PARKER (alternate member for the United States of America) M. LE PROFESSEUR DONNEDIEU DE VABRES (member for the French Republic) M. LE CONSEILER FLACO (alternate member for the French Republic) MAJOR-GENERAL I. T. NIKITCHENKO (member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) LT.-COLONEL A. F. VOLCHKOV (alternate member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) {iv} THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, AND THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS Against: Hermann Wilhelm Göring, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Robert Ley, Wilhelm Keitel, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Alfred Rosenberg, Hans Frank, Wilhelm Frick, Julius Streicher, Walter Funk, Hjalmar Schacht, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, Karl Dönitz, Erich Raeder, Baldur von Schirach, Fritz Sauckel, Alfred Jodl, Martin -

Overlord - 1944

Overlord - 1944 Bracknell Paper No 5 A Symposium on the Normandy Landings 25 March 1994 Sponsored jointly by the Royal Air Force Historical Society and the Royal Air Force Staff College, Bracknell ii OVERLORD – 1944 Copyright ©1995 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society First Published in the UK in 1995 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 0 9519824 3 5 Typesetting and origination by Alan Sutton Publishing Ltd Printed in Great Britain by Hartnolls, Bodmin, Cornwall. Royal Air Force Historical Society OVERLORD – 1944 iii Contents Frontispiece Preface 1. Welcome by the Commandant, Air Vice-Marshal M P Donaldson 2. Introductory Remarks by the Chairman, Air Chief Marshal Sir Michael Armitage 3. Overlord – The Broad Context: John Terraine 4. The Higher Command Structures and Commanders: Field Marshal the Lord Bramall 5. Air Preparations: Air Marshal Sir Denis Crowley-Milling 6. Planning the Operation: Lt General Sir Napier Crookenden and Air Marshal Sir Denis Crowley-Milling 7. The Luftwaffe Role – Situation and Response: Dr Horst Boog 8. The Overlord Campaign: Lt General Crookenden and Air Marshal Crowley-Milling 9. Digest of the Group Discussions 10. Chairman’s Closing Remarks 11. Biographical Notes on Main Speakers The Royal Air Force Historical Society iv OVERLORD – 1944 OVERLORD – 1944 v Preface The fifth in the World War Two series of Bracknell Symposia, Overlord – 1944, was held at the RAF Staff College on March 25th. -

© Osprey Publishing • © Osprey Publishing • HITLER’S EAGLES

www.ospreypublishing.com © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com HITLER’S EAGLES THE LUFTWAFFE 1933–45 Chris McNab © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS Introduction 6 The Rise and Fall of the Luftwaffe 10 Luftwaffe – Organization and Manpower 56 Bombers – Strategic Reach 120 Fighters – Sky Warriors 174 Ground Attack – Strike from Above 238 Sea Eagles – Maritime Operations 292 Ground Forces – Eagles on the Land 340 Conclusion 382 Further Reading 387 Index 390 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION A force of Heinkel He 111s near their target over England during the summer of 1940. Once deprived of their Bf 109 escorts, the German bombers were acutely vulnerable to the predations of British Spitfires and Hurricanes. © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com he story of the German Luftwaffe (Air Force) has been an abiding focus of military Thistorians since the end of World War II in 1945. It is not difficult to see why. Like many aspects of the German war machine, the Luftwaffe was a crowning achievement of the German rearmament programme. During the 1920s and early 1930s, the air force was a shadowy organization, operating furtively under the tight restrictions on military development imposed by the Versailles Treaty. Yet through foreign-based aircraft design agencies, civilian air transport and nationalistic gliding clubs, the seeds of a future air force were nevertheless kept alive and growing in Hitler’s new Germany, and would eventually emerge in the formation of the Luftwaffe itself in 1935. The nascent Luftwaffe thereafter grew rapidly, its ranks of both men and aircraft swelling under the ambition of its commander-in-chief, Hermann Göring. -

I Bf 109E-4, Wnr. 5375, Flown by Hptm. Wilhelm

ADLERANGRIFF in Scandinavia and focused on action over eastern Scotland. With bases in Western Europe, Luftotte 2 concentrated their efforts on eastern England and Luftotte 3 was to focus on western England and Wales. Fighter wings armed with single engined aircraft (Jagdgeschwader) during the spring of 1940 were taking delivery of the modernized Bf 109E-4, which were equ-i pped with a pair of 20mm MG FF/M cannon in the wings, instead of the MG FF that was in the Bf 109E-3. The redesigned cockpit canopy allowed for the installation of a larger armoured plate behind the pilot’s head, and for the easier installation of an armoured windscreen. However, this version still did not offer the option of a long range tank under the fuselage. This resulted in limited range for the Bf 109s used against England, and the Bf 109E-7, which did accommodate a drop tank, did not come into service until after the Battle of Britain, in November 1940. The older E-3, with two cannon and two 7.92mm machine guns, and the ‘light’ E-1 version, armed with four of the 7.92mm guns, were, surprisingly, in production until August 1940. To facilitate the Bf 109’s use as a ghter-bomber, German aircraft manufacturers were producing the E-1/B and the E-4/B, equipped with fuselage racks for 250kg bombs. Another modication, albeit less common, was in the installation of the DB 601N engine, rated at 1175k. So-equipped aircraft were designated Bf 109E-3/N or E-4/N, and required the use of 100octane fuel, C3. -

Readers' Guide

Breaking Point — Readers’ Guide Readers’ Guide Breaking Point — Readers’ Guide ABOUT THE NOVEL Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this Island or lose the war (Winston Churchill) The hour will come when one of us will break—and it will not be National Socialist Germany (Adolf Hitler) And now the hour has come … It is August, 1940. Hitler’s triumphant Third Reich has crushed all Europe—except Britain. As Hitler launch- es a massive aerial assault, only the heavily outnumbered Fighter Command and the iron will of Winston Churchill can stop him. Johnnie Shaux, a Spitfire fighter pilot, must summon up the fortitude to fly into conditions in which death is all but inevitable, and continue to do so until the inevitable occurs... Eleanor Rand, a brilliant Fighter Command mathematician, must find her role in a man’s world. She studies the control room map tracking the ebbs and flows of the conflict, and sees the glimmerings of a radical break- through… Breaking Point is based on actual events in the Battle of Britain. The story alternates between Johnnie, face to face with the enemy, and Eleanor, using ‘zero-sum’ mathematical theory to evolve a strategic model of the battle. Their parallel stories merge as the battle reaches its climax and they confront danger together. Breaking Point — Readers’ Guide ABOUT THE AUTHOR John Rhodes was born in World War II while his father was serving at an RAF Fighter Command airfield in southern England. After the war he grew up in London, where, he says, the shells of bombed-out buildings ‘served as our adventure playgrounds.’ Rhodes graduated from Cambridge University where he studied history.