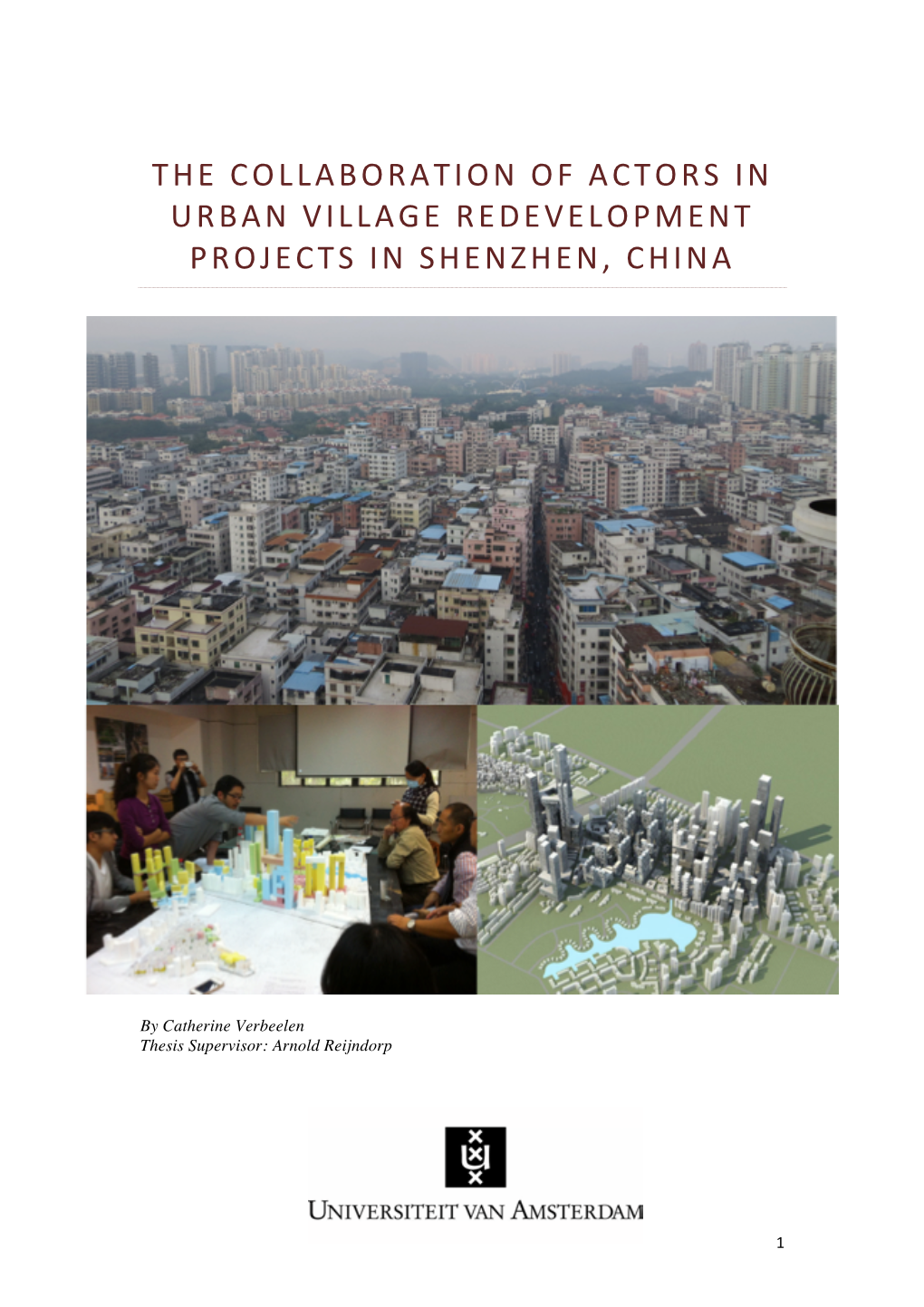

The Collaboration of Actors in Urban Village Redevelopment Projects in Shenzhen, China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relationship Between Urbanization And

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN URBANIZATION AND POSITIVE SOCIAL BEHAVIOUR: A STUDY OF HELPFULNESS BETWEEN STRANGERS IN VARIOUS TYPE OF URBAN ENVIRONMENTS AS AN INDICATION OF QUALITY OF SOCIAL LIFE POSİTİF SOSYAL DAVRANIŞ VE ŞEHİRLEŞME ARASINDAKİ İLİŞKİ: ŞEHİRDE SOSYAL HAYAT KALİTESİNİN ANLAŞILMASI BAKIMINDAN BİRBİRİNİ TANIMAYAN İKİ FERT ARASINDAKİ YARDIMLAŞMANIN İNCELENMFSİ NAMIK AYVALIOĞLU Department of Psychology, University of istanbul A field study was carried out in Turkey in order to compare the level of helpfulness in town, cities, and urban squatter settle ments. Four different naturalistic measures of helpfulness were de- velopted and used: willingness to give change, willingness to coope rate with an interview, response to a small accident, and response to a lost postcard. The results generally showed significantly less helpfulness in Turkish cities than in towns and urban squatter settle ments, which showed equivalent levels of helpfulness. This supports the view that the squatters may in a pschological and social sense be «urban villagers». Consistent and considerable differences in helpful ness were also found between other typs of city districts. Some of these districts came close to the towns and squatter settle ments in their levels of helpfulness, suggesting that drawing distinc tions between environments in terms of their behavioral characte ristics is best done with the concept of a social-enviromental conti nuum rather than an urban-nonurban dichotomy. Also environmental input level as an explanation of urban social behaviour was tested in naturalistic environments, found to influence the level of help fulness for female subjects but not male subjects. Finally, a survey 106 NAMIK AYVALIOĞLU study was carried out in order to examine differences in attitudes of helpfulness between environements in the question. -

Urban Villages in China NIE, Zhi-Gang and WONG, Kwok-Chun

Urban Villages in China NIE, Zhi-Gang and WONG, Kwok-Chun Department of Real Estate and Construction University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong Email: [email protected] Abstract: There are two main types of land ownership in China – state owned land, and land owned by village communes. During the rapid urbanization of China in the past 30 years, state owned lands were sold and developed into high densities apartments. These apartments were built literally surrounding existing rural villages. Village lands were, however, not allowed to be developed because of its rural history. But when the villagers saw the profits of development, they simply build new apartments illegally at rates and densities even higher than those on state owned lands. By now, the political problems of these illegal developments are too large to be handled by local city governments. Hence, as we now see, there are high density apartments built by villagers right inside city centres. Very often these apartments are poorer in qualities. This paper traces the history of this development, and tries to induce property right implications on excessive land exploitation, in the absence of effective building regulation and control. Keywords: building regulation and control, property rights, state owned land, urban villages, village communes. 1 Historical background In mainland China, there was basically a feudal land system before the Chinese Revolution in 1911. After 1911, a system of private land ownership was still, by and large, enforced by the Chinese Nationalist Party. The Communist Land Reform started in 1946. Basically in this reform, land and other properties of landlords were expropriated and redistributed. -

Mary-Ann Ray STUDIO WORKS ARCHITECTS 1800 Industrial

Mary-Ann Ray STUDIO WORKS ARCHITECTS 1800 Industrial Street Los Angeles, CA 90021 213 623 7075 213 623 7335 fax UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Alfred A. Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning Ann Arbor, MI BASE Beijing Beijing, P.R. CHINA [email protected] [email protected] www.studioworksarchitects.com www.basebeijing.cn www.basebeijing.tumblr.com Ms. Ray is the Taubman Centennial Professor of Practice at the University of Michigan’s Alfred A. Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning. She has also held numerous prestigious visiting chair positions at other institutions including the Saarinen Professor at Yale University and the Wortham Professor at Rice University. Ms. Ray was the Chair of Environmental Arts at Otis College of Art and Design from 1997 – 1999. Professionally, Mary-Ann Ray is a Principal of Studio Works Architects in Los Angeles and a Co- Founder and Director of BASE Beijing. Studio Works is a world renowned award winning design firm whose design work and research have been widely published. Mary-Ann Ray and her partner Robert Mangurian are architects, authors, and designers, and in 2001 they were awarded the prestigious Chrysler Design Award for Excellence and Innovation in an ongoing body of work in a design field. In 2008 they were awarded the Stirling Prize for the Memorial Lecture on the City by the Canadian Centre for Architecture and the London School of Economics. Among her published books are Pamphlet Architecture No. 20 Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice and Midgets, Wrapper, and the recent Caochangdi: Beijing Inside Out. Ray is a Rome Prize recipient and Fellow of the American Academy in Rome. -

The Design Dimension of China's Planning System: Urban Design for Development Control

International Planning Studies ISSN: 1356-3475 (Print) 1469-9265 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cips20 The design dimension of China's planning system: urban design for development control Fei Chen To cite this article: Fei Chen (2016) The design dimension of China's planning system: urban design for development control, International Planning Studies, 21:1, 81-100 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2015.1114452 © 2015 The Author(s). Published by Taylor & Francis. Published online: 18 Dec 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cips20 Download by: [University of Liverpool] Date: 18 December 2015, At: 05:28 INTERNATIONAL PLANNING STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 21, NO. 1, 81–100 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2015.1114452 The design dimension of China’s planning system: urban design for development control Fei Chen School of Architecture, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK ABSTRACT This paper investigates the design dimension of China’s legal planning framework. It aims to identify the design principles which have been followed in practice, those design elements which have been considered by designers and planners as part of development control, and the extent to which urban design outcomes have been adopted in specific legal plans. It examines 14 urban design cases from Nanjing which were produced in conjunction with the relevant legal plans between 2009 and 2013. The study suggests that in China, urban design has been facing a number of challenges, including limited coverage of design elements, inconsistencies in the design principles followed, an incompatibility between design outcomes and legal plans, and an underestimation of the role of urban design in the delivery process of development control. -

Comprehensive Plan Urban Village Indicators Monitoring Report Was Prepared by the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD), June 2018

Comprehensive Plan URBAN VILLAGE INDICATORS MONITORING REPORT 2018 Contacts & Acknowledgements The Comprehensive Plan Urban Village Indicators Monitoring Report was prepared by the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD), June 2018 CONTACTS: Diana Canzoneri, City Demographer, OPCD, [email protected], Michael Hubner, Comprehensive Planning Manager, OPCD, [email protected] Jason W. Kelly, Communications Director, OPCD, [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: We appreciate the time, thought, and data that contributing organizations and individuals provided to make this first monitoring report happen. Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) Samuel Assefa Tom Hauger Diana Canzoneri Michael Hubner Patrice Carroll Jeanette Martin Ian Dapiaoen Claire Palay David Driskell Jennifer Pettyjohn Cayce James Bernardo Serna Jason W. Kelly Katie Sheehy Penelope Koven Nick Welch Geoffrey Gund Geoff Wentlandt Mayor’s Office Sara Maxana City Council Central Legislative Staff Lish Whitson Office of Housing (OH) Emily Alvarado Mike Kent Nathan Haugen Robin Koskey Laura Hewitt Walker Miriam Roskin Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) Moon Callison Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) Emily Burns Adam Parast Chad Lynch Rachel VerBoort Nico Martinucci Christopher Yake Seattle IT Patrick Morgan Rodney Young Seattle Parks and Recreation (SPR) Susanne Rockwell Seattle Planning Commission Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................ -

Urban Governance of Economic Upgrading Processes in China the Case of Guangzhou Science City

Internationales Asienforum, Vol. 41 (2010), No. 1–2, pp. 57–82 Urban Governance of Economic Upgrading Processes in China The Case of Guangzhou Science City FRIEDERIKE SCHRÖDER / MICHAEL WAIBEL Introduction China’s export-oriented regions such as the so-called “factory of the world” – the Pearl River Delta1 (PRD) in south China – have been particularly affected by the global financial and economic crisis. Thousands of migrants mostly working in the low value-added manufacturing sector were laid off due to the closure of plants virtually overnight. However, the crisis hit the region in the middle of a deliberately planned economic upgrading process encouraging the shift of its economic structure from labor-intensive manu- facturing towards higher value-added services and high-tech2 industries. This upgrading process is embedded in the national “Plan for the Reform and Development of the Pearl River Delta (2008 to 2020)” initiated by the National Reform and Development Commission. Hereby, national and provincial governments are seeking to build up a more advanced industrial system by prioritizing the development of modern service industries such as _______________ 1 The PRD is variously defined. In our paper we use this term to include the cities of Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Dongguan, Foshan, Zhongshan, Zhuhai, as well as parts of Huizhou and Zhaoqing. This priority development area was designated as “Pearl River Delta Open Economic Region” by the State Council of People Government of China in the mid-1980s (Philipps & Yeh, 1990). The inclusion of the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macao in this spatial entity is commonly referred to as the so- called “Greater Pearl River Delta”. -

Rebel Cities: from the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution

REBEL CITIES REBEL CITIES From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution David Harvey VERSO London • New York First published by Verso 20 12 © David Harvey All rights reserved 'Ihe moral rights of the author have been asserted 13579108642 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London WI F OEG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 1120 I www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books eiSBN-13: 978-1-84467-904-1 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harvey, David, 1935- Rebel cities : from the right to the city to the urban revolution I David Harvey. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-84467-882-2 (alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-84467-904-1 I. Anti-globalization movement--Case studies. 2. Social justice--Case studies. 3. Capitalism--Case studies. I. Title. HN17.5.H355 2012 303.3'72--dc23 2011047924 Typeset in Minion by MJ Gavan, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Vail For Delfina and all other graduating students everywhere Contents Preface: Henri Lefebvre's Vision ix Section 1: The Right to the City The Right to the City 3 2 The Urban Roots of Capitalist Crises 27 3 The Creation of the Urban Commons 67 4 The Art of Rent 89 Section II: Rebel Cities 5 Reclaiming the City for Anti-Capitalist Struggle 115 6 London 201 1: Feral Capitalism Hits the Streets 155 7 #OWS: The Party of Wall Street Meets Its Nemesis 159 Acknowledgments 165 Notes 167 Index 181 PREFACE Henri Lefebvre's Vision ometime in the mid 1970s in Paris I came across a poster put out by S the Ecologistes, a radical neighborhood action movement dedicated to creating a more ecologically sensitive mode of city living, depicting an alternative vision for the city. -

Wang, Weikai (2020) the Discourse, Governance and Configurations of Polycentricity in Transitional China: a Case Study of Tianjin

Wang, Weikai (2020) The discourse, governance and configurations of polycentricity in transitional China: a case study of Tianjin. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/81666/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Discourses, Governance and Configurations of Polycentricity in Transitional China: A Case Study of Tianjin Weikai Wang BSc, MSc Peking University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Philosophy School of Social and Political Sciences College of Social Science University of Glasgow September 2020 Abstract Polycentricity has been identified as a prominent feature of modern landscapes as well as a buzzword in spatial planning at a range of scales worldwide. Since the Reform and Opening- up Policy in 1978, major cities in China have experienced significant polycentric transition manifested by their new spatial policy framework and reshaped spatial structure. The polycentric transformation has provoked academics’ interests on structural and performance analysis in quantitative ways recently. However, little research investigates the nature of (re)formation and implementation of polycentric development policies in Chinese cities from a processual and critical perspective. -

Researching the Urban Dilemma: Urbanization, Poverty and Violence

Researching the Urban Dilemma: Urbanization, Poverty and Violence By Robert Muggah Copyright © IDRC, May 2012 Cover artwork designed by Scott Sigurdson, www.scottsigurdson.com Table of Contents Preface .................................................................................................................................................................... iii About the Author..................................................................................................................................................... v Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................ vi Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Report Methodology ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Section 1: Research and Methods ........................................................................................................................... 7 Section 2: Concepts and Theories ......................................................................................................................... 13 i. Defining the “urban” ................................................................................................................................. 15 ii. Defining urban violence ............................................................................................................................ -

Urbanization and Urbanism As a Way of Life: the Case of Konya As a Metropolitan Village in Turkey

E-ISSN 2281-4612 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Vol 2 No 8 ISSN 2281-3993 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy October 2013 Urbanization and Urbanism as a Way of Life: The Case of Konya as a Metropolitan Village in Turkey Ass.Prof.Dr. Özgür SarÖ Selçuk University Department of Sociology Doi:10.5901/ajis.2013.v2n8p260 Abstract Cities and urban has being studied not only by architecture, city planning, but also politics, sociology, economics, and geography; therefore, urban studies is an interdisciplinary area that aims to understand the process of urbanization and cities as characteristics of 20th and 21st centuries. Different fields recognize that urbanization is not only physical process occurring on space, but a social and economic process that affects the social behaviors of people. Higher population density and higher buildings are not only indicators of urbanization, but also there are some other indicators of social behavior that show us urbanization. To being urbanized, scholars are expecting some behavior habits and patterns from the living people. Around the theoretical arguments of social phenomenon of urbanization, the case of Konya will be analyzed. While, Konya is being accepted as metropolitan city including service and industrial sectors and population density, living people in Konya is still having traditional patterns regarding to rural. The study will be strengthened with the researches on social patterns of people living in Konya, conducted by the Konya Metropolitan Municipality. Keywords: Urbanization, Urbanism, Metropolitan Village, Urban, Rural. 1. Introduction 76.8 % of the population is living in urban in Turkey (http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=10736), and 18.2 % of the total population is living only in one city, Istanbul. -

China's Master Planning System in Transition Case Study on Beijing

Gu Chaolin, Yuan Xiaohui and Guo Jing, China’s master planning system in transition: case study of Beijing, 46th ISOCARP Congress 2010 China’s master planning system in transition Case study on Beijing Gu Chaolin Yuan Xiaohui Guo Jing 1. Introduction Ever since China reformed and opened up to the world in 1978, there were immense changes taken place in structure and system framework of society, economy and space. The service industry has entered the fast development track and the economic structure is speedily adjusting. Millions of farmers left their land to look for new development. In this period, industrialization and urbanization kept pushing forward. Thus, the conflicts between rural and urban development deteriorated and social migration is increasing. The largest dualistic economy entity in the world is changing. During this period, resource consumption increases rapidly in volume and environmental pressure continues to increase. In fact, China’s urban planning system play an important role for its development and growth as well as resource and environmental problems. This paper will discuss the great changes of the China’s urban planning system and have a Beijing case study during that time. In general, Urban planning in China first 30 years used the former Soviet Union urban planning model according to the planned economy system. Urban planning is implementation in space of the state economic development plans. The second 30 years exploring national conditions of the socialist market economic system in urban planning. Traditional urban planning system is broken and the new planning system also can not copy urban planning system from the European market economy countries. -

Dwelling in Shenzhen: Development of Living Environment from 1979 to 2018

Dwelling in Shenzhen: Development of Living Environment from 1979 to 2018 Xiaoqing Kong Master of Architecture Design A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2020 School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract Shenzhen, one of the fastest growing cities in the world, is the benchmark of China’s new generation of cities. As the pioneer of the economic reform, Shenzhen has developed from a small border town to an international metropolis. Shenzhen government solved the housing demand of the huge population, thereby transforming Shenzhen from an immigrant city to a settled city. By studying Shenzhen’s housing development in the past 40 years, this thesis argues that housing development is a process of competition and cooperation among three groups, namely, the government, the developer, and the buyers, constantly competing for their respective interests and goals. This competing and cooperating process is dynamic and needs constant adjustment and balancing of the interests of the three groups. Moreover, this thesis examines the means and results of the three groups in the tripartite competition and cooperation, and delineates that the government is the dominant player responsible for preserving the competitive balance of this tripartite game, a role vital for housing development and urban growth in China. In the new round of competition between cities for talent and capital, only when the government correctly and effectively uses its power to make the three groups interacting benignly and achieving a certain degree of benefit respectively can the dynamic balance be maintained, thereby furthering development of Chinese cities.