The Ghost Ship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

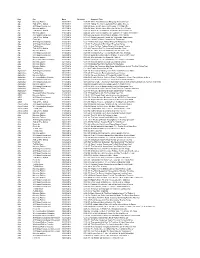

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0:04:09 When Should Seniors Hang Up The Car Keys? Age Talk Of The Nation 10/15/2012 0:30:20 Taking The Car Keys Away From Older Drivers Age All Things Considered 10/16/2012 0:05:29 Home Health Aides: In Demand, Yet Paid Little Age Morning Edition 10/17/2012 0:04:04 Home Health Aides Often As Old As Their Clients Age Talk Of The Nation 10/25/2012 0:30:21 'Elders' Seek Solutions To World's Worst Problems Age Morning Edition 11/01/2012 0:04:44 Older Voters Could Decide Outcome In Volatile Wisconsin Age All Things Considered 11/01/2012 0:03:24 Low-Income New Yorkers Struggle After Sandy Age Talk Of The Nation 11/01/2012 0:16:43 Sandy Especially Tough On Vulnerable Populations Age Fresh Air 11/05/2012 0:06:34 Caring For Mom, Dreaming Of 'Elsewhere' Age All Things Considered 11/06/2012 0:02:48 New York City's Elderly Worry As Temperatures Dip Age All Things Considered 11/09/2012 0:03:00 The Benefit Of Birthdays? Freebies Galore Age Tell Me More 11/12/2012 0:14:28 How To Start Talking Details With Aging Parents Age Talk Of The Nation 11/28/2012 0:30:18 Preparing For The Looming Dementia Crisis Age Morning Edition 11/29/2012 0:04:15 The Hidden Costs Of Raising The Medicare Age Age All Things Considered 11/30/2012 0:03:59 Immigrants Key To Looming Health Aide Shortage Age All Things Considered 12/04/2012 0:03:52 Social Security's COLA: At Stake In 'Fiscal Cliff' Talks? Age Morning Edition 12/06/2012 0:03:49 Why It's Easier To Scam The Elderly Age Weekend Edition Saturday 12/08/2012 -

The New York City Draft Riots of 1863

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1974 The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 Adrian Cook Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cook, Adrian, "The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863" (1974). United States History. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/56 THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS This page intentionally left blank THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS TheNew York City Draft Riots of 1863 ADRIAN COOK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY ISBN: 978-0-8131-5182-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-80463 Copyright© 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix -

Legacy, Vol. 17, 2017

2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship A Publication of the Sigma Kappa Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta A Publication of the Sigma Kappa & the Southern Illinois University Carbondale History Department & the Southern Illinois University Volume 17 Volume LEGACY • A Journal of Student Scholarship • Volume 17 • 2017 LEGACY Volume 17 2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship Editorial Staff Denise Diliberto Geoff Lybeck Gray Whaley Faculty Editor Hale Yılmaz The editorial staff would like to thank all those who supported this issue of Legacy, especially the SIU Undergradute Student Government, Phi Alpha Theta, SIU Department of History faculty and staff, our history alumni, our department chair Dr. Jonathan Wiesen, the students who submitted papers, and their faculty mentors Professors Jo Ann Argersinger, Jonathan Bean, José Najar, Joseph Sramek and Hale Yılmaz. A publication of the Sigma Kappa Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta & the History Department Southern Illinois University Carbondale history.siu.edu © 2017 Department of History, Southern Illinois University All rights reserved LEGACY Volume 17 2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship Table of Contents The Effects of Collegiate Gay Straight Alliances in the 1980s and 1990s Alicia Mayen ....................................................................................... 1 Students in the Carbondale, Illinois Civil Rights Movement Bryan Jenks ...................................................................................... 15 The Crisis of Legitimacy: Resistance, Unity, and the Stamp Act of 1765, -

Riis's How the Other Half Lives

How the Other Half Lives http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/title.html HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVES The Hypertext Edition STUDIES AMONG THE TENEMENTS OF NEW YORK BY JACOB A. RIIS WITH ILLUSTRATIONS CHIEFLY FROM PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN BY THE AUTHOR Contents NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1890 1 of 1 1/18/06 6:25 AM Contents http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/contents.html HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVES CONTENTS. About the Hypertext Edition XII. The Bohemians--Tenement-House Cigarmaking Title Page XIII. The Color Line in New York Preface XIV. The Common Herd List of Illustrations XV. The Problem of the Children Introduction XVI. Waifs of the City's Slums I. Genesis of the Tenements XVII. The Street Arab II. The Awakening XVIII. The Reign of Rum III. The Mixed Crowd XIX. The Harvest of Tare IV. The Down Town Back-Alleys XX. The Working Girls of New York V. The Italian in New York XXI. Pauperism in the Tenements VI. The Bend XXII. The Wrecks and the Waste VII. A Raid on the Stale-Beer Dives XXIII. The Man with the Knife VIII.The Cheap Lodging-Houses XXIV. What Has Been Done IX. Chinatown XXV. How the Case Stands X. Jewtown Appendix XI. The Sweaters of Jewtown 1 of 1 1/18/06 6:25 AM List of Illustrations http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/illustrations.html LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. Gotham Court A Black-and-Tan Dive in "Africa" Hell's Kitchen and Sebastopol The Open Door Tenement of 1863, for Twelve Families on Each Flat Bird's Eye View of an East Side Tenement Block Tenement of the Old Style. -

Eau Brummels of Gangland and the Killing They Did in Feuds Ho" It

1 9 -- THE SUN; SUNDAY, AtlGtlSTriSWi 1! eau Brummels of Gangland and the Killing They Did in Feuds ho" it v" A!. W4x 1WJ HERMAN ROSEHTHAL WHOSE K.1LLINQ- - POLICE COMMISSIOKER. EH RIGHT WHO IS IN $ MARKED T?e expressed great indignation that a KEEPING TJe GANGS SUBdECTIOK. BEGINNING-O- F crime had been committed. Ploggl .TAe stayed in. hiding for a few days whllo tho politicians who controlled the elec END FOR. tion services of the Five Points ar- ranged certain matters, and then ho Slaying of Rosenthal Marked the Be surrendered. Of courso ho pleaded e. ginning of the End for Gangs Whose "Biff" Ellison, who was sent to Sing Sing for his part In the killing of by Bill Harrington in Paul Kelly's New Grimes Had Been Covered a Brighton dive, came to the Bowery from Maryland when he was in his Crooked Politicians Some of WHERE early twenties. Ho got a Job' as ARTHUR. WOOD5P WHO PUT T5e GANGS bouncer in Pat Flynn's saloon in 34 Reformed THEY ObLUncr. Bond street, and advanced rapidly in Old Leaders Who tho estimation of gangland, because he was young and husky when he and zenship back Tanner Smith becamo as approaching tho end of his activities. hit a man that man went down and r 0 as anybody. Ho got Besides these there were numerous stayed down. That was how he got decent a citizen Murders Resulting From Rivalry Among Gangsters Were a Job as beef handler on the docks, other fights. bis nickname ho used to be always stevedore, and threatening to someone. -

Calvi Full Dissertation April 20 11 Deposit

1 THE PARROT AND THE CANNON. JOURNALISM, LITERATURE AND POLITICS IN THE FORMATION OF LATIN AMERICAN IDENTITIES By Pablo L. Calvi Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2011 2 © 2011 Pablo Calvi All rights reserved 3 Abstract THE PARROT AND THE CANNON. JOURNALISM, LITERATURE AND POLITICS IN THE FORMATION OF LATIN AMERICAN IDENTITIES Pablo Calvi The Parrot and the Cannon. Journalism, Literature and Politics in the Formation of Latin American Identities explores the emergence of literary journalism in Latin America as a central aspect in the formation of national identities. Focusing on five periods in Latin American history from the post-colonial times until the 1960s, it follows the evolution of this narrative genre in parallel with the consolidation of professional journalism, the modern Latin American mass media and the formation of nation states. In the process, this dissertation also studies literary journalism as a genre, as a professional practice, and most importantly as a political instrument. By exploring the connections between journalism, literature and politics, this dissertation also illustrates the difference between the notions of factuality, reality and journalistic truth as conceived in Latin America and the United States, while describing the origins of Latin American militant journalism as a social-historical formation. i Table of Contents Introduction. The Place of Literary -

Organizovaný Zločin V První Polovině 20. Století

Západo česká univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Diplomová práce Organizovaný zlo čin v první polovin ě 20. století Kokaislová Lucie Plze ň 2014 Západo česká univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra historických v ěd Studijní program Historické v ědy Studijní obor Moderní d ějiny Diplomová práce Organizovaný zlo čin v první polovin ě 20. století Kokaislová Lucie Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Roman Kodet, Ph.D. Katedra historických v ěd Fakulta filozofická Západo české univerzity v Plzni Plze ň 2014 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracoval(a) samostatn ě a použil(a) jen uvedených pramen ů a literatury. Plze ň, duben 2014 ......................................... Obsah Úvod .................................................................................................................. 5 1 Italská mafie................................................................................................ 11 1.1. Sicilská mafie ........................................................................................................... 13 1.1.1. Pojem, struktura a inicia ční rituál ..................................................................... 14 1.1.2. Otázka vzniku a p ůvodu, a dokumenty popisující uskupení podobná mafii ...... 17 1.1.3. Vývoj .................................................................................................................. 20 1.2. Camorra ................................................................................................................... 25 1.2.1. P ůvod, pojem, inicia ční rituál a struktura -

Old Heads Tell Their Stories: from Street Gangs to Street Organizations in New York City

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 412 305 UD 031 930 AUTHOR Brotherton, David C. TITLE Old Heads Tell Their Stories: From Street Gangs to Street Organizations in New York City. SPONS AGENCY Spencer Foundation, Chicago, IL. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 35p. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adults; *Delinquency; Illegal Drug Use; *Juvenile Gangs; *Leadership; Neighborhoods; Role Models; Urban Areas; *Urban Youth IDENTIFIERS *New York (New York); Street Crime ABSTRACT It has been the contention of researchers that the "old heads" (identified by Anderson in 1990 and Wilson in 1987) of the ghettos and barrios of America have voluntarily or involuntarily left the community, leaving behind new generations of youth without adult role models and legitimate social controllers. This absence of an adult strata of significant others adds one more dynamic to the process of social disorganization and social pathology in the inner city. In New York City, however, a different phenomenon was found. Older men (and women) in their thirties and forties who were participants in the "jacket gangs" of the 1970s and/or the drug gangs of the 1980s are still active on the streets as advisors, mentors, and members of the new street organizations that have replaced the gangs. Through life history interviews with 20 "old heads," this paper traces the development of New York City's urban working-class street cultures from corner gangs to drug gangs to street organizations. It also offers a critical assessment of the state of gang theory. Analysis of the development of street organizations in New York goes beyond this study, and would have to include the importance of street-prison social support systems, the marginalization of poor barrio and ghetto youth, the influence of politicized "old heads," the nature of the illicit economy, the qualitative nonviolent evolution of street subcultures, and the changing role of women in the new subculture. -

In 193X, Constance Rourke's Book American Humor Was Reviewed In

OUR LIVELY ARTS: AMERICAN CULTURE AS THEATRICAL CULTURE, 1922-1931 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Schlueter, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Thomas Postlewait, Adviser Professor Lesley Ferris Adviser Associate Professor Alan Woods Graduate Program in Theatre Copyright by Jennifer Schlueter c. 2007 ABSTRACT In the first decades of the twentieth century, critics like H.L. Mencken and Van Wyck Brooks vociferously expounded a deep and profound disenchantment with American art and culture. At a time when American popular entertainments were expanding exponentially, and at a time when European high modernism was in full flower, American culture appeared to these critics to be at best a quagmire of philistinism and at worst an oxymoron. Today there is still general agreement that American arts “came of age” or “arrived” in the 1920s, thanks in part to this flogging criticism, but also because of the powerful influence of European modernism. Yet, this assessment was not, at the time, unanimous, and its conclusions should not, I argue, be taken as foregone. In this dissertation, I present crucial case studies of Constance Rourke (1885-1941) and Gilbert Seldes (1893-1970), two astute but understudied cultural critics who saw the same popular culture denigrated by Brooks or Mencken as vibrant evidence of exactly the modern American culture they were seeking. In their writings of the 1920s and 1930s, Rourke and Seldes argued that our “lively arts” (Seldes’ formulation) of performance—vaudeville, minstrelsy, burlesque, jazz, radio, and film—contained both the roots of our own unique culture as well as the seeds of a burgeoning modernism. -

The Kingpins Old Pensacola

THE KINGPINS OLD PENSACOLA The Prime Minister Old Fashioned 12 Frosé All Day 10 [Spring Edition] Hendricks gin, elderflower, Lichi-Li, Pamplemouse, Woodford Reserve bourbon, muddled orange & Matua rosé, lime, fresh juices. Maraschino cherry, Maraschino liqueur, cane syrup, nut bitters, candied bacon, brandy soaked Bing cherry. The Wentworth jr Martini 10 Fords gin, Wheatley vodka, Lillet Blanc, olive juice, hand The Al Capone Manhattan 12 stuffed Statesboro blue cheese olives. Templeton’s Rye Whiskey, Carpano Antica Formula sweet vermouth, Monarch bacon & tobacco bitters, Santa Rosa Martini 10 poured over local honey comb, Luxardo cherry, smoked Fresh cucumber, Hendrick’s gin, St. Germain elderflower hog jowl. liqueur, rose syrup, lime juice. Five Flags Spicy Paloma 11 The Lucky Sazerac 10 Montelobos Mezcal Joven, Ancho Reyes chile liqueur, Redemption rye whiskey, Absinthe, Creole bitters, blood orange sour, ruby red grapefruit juice, lime juice, Peychaud’s liqueur, cane syrup, lemon peel. cayenne pepper rim. The Nucky French 75 9 The Mighty O Margarita 10 Malfy Con Limone gin, lavender syrup, lemon, topped Milagro silver tequila, Grand Marnier, lime juice, agave with Veuve du Vernay Brut Rosé, sprig of thyme. nectar, orange squeeze, salted rim. The Forty Thieves Bramble 9 The Galvez Mojito 10 [Spring Edition] Fresh lime & mint, China China herbal liqueur, Macerated Florida strawberries, Bosfords strawberry rose cane syrup, lemon lime soda. gin, Giffard rhubarb liqueur, lemon, sugar cane. Keto My Heart Mojito 11 Fresh lime & mint, Ketel One peach & orange blossom, The Five Points Gang 10 D’orange vermouth, stevia, soda. Muddled red bell pepper, Loch Lomond single malt scotch, Giffard apricot liqueur, Ancho Reyes chili liqueur, citric acid, can syrup, Madeira float. -

Community and Politics in Antebellum New York City Irish Gang Subculture James

The Communal Legitimacy of Collective Violence: Community and Politics in Antebellum New York City Irish Gang Subculture by James Peter Phelan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©James Phelan, 2014 ii Abstract This thesis examines the influences that New York City‘s Irish-Americans had on the violence, politics, and underground subcultures of the antebellum era. During the Great Famine era of the Irish Diaspora, Irish-Americans in Five Points, New York City, formed strong community bonds, traditions, and a spirit of resistance as an amalgamation of rural Irish and urban American influences. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Irish immigrants and their descendants combined community traditions with concepts of American individualism and upward mobility to become an important part of the antebellum era‘s ―Shirtless Democracy‖ movement. The proto-gang political clubs formed during this era became so powerful that by the late 1850s, clashes with Know Nothing and Republican forces, particularly over New York‘s Police force, resulted in extreme outbursts of violence in June and July, 1857. By tracking the Five Points Irish from famine to riot, this thesis as whole illuminates how communal violence and the riots of 1857 may be understood, moralised, and even legitimised given the community and culture unique to Five Points in the antebellum era. iii Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... -

The Global Irish and Chinese: Migration, Exclusion, and Foreign Relations Among Empires, 1784-1904

THE GLOBAL IRISH AND CHINESE: MIGRATION, EXCLUSION, AND FOREIGN RELATIONS AMONG EMPIRES, 1784-1904 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Barry Patrick McCarron, M.A. Washington, DC April 6, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Barry Patrick McCarron All Rights Reserved ii THE GLOBAL IRISH AND CHINESE: MIGRATION, EXCLUSION, AND FOREIGN RELATIONS AMONG EMPIRES, 1784-1904 Barry Patrick McCarron, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Carol A. Benedict, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation is the first study to examine the Irish and Chinese interethnic and interracial dynamic in the United States and the British Empire in Australia and Canada during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Utilizing comparative and transnational perspectives and drawing on multinational and multilingual archival research including Chinese language sources, “The Global Irish and Chinese” argues that Irish immigrants were at the forefront of anti-Chinese movements in Australia, Canada, and the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century. Their rhetoric and actions gave rise to Chinese immigration restriction legislation and caused major friction in the Qing Empire’s foreign relations with the United States and the British Empire. Moreover, Irish immigrants east and west of the Rocky Mountains and on both sides of the Canada-United States border were central to the formation of a transnational white working-class alliance aimed at restricting the flow of Chinese labor into North America. Looking at the intersections of race, class, ethnicity, and gender, this project reveals a complicated history of relations between the Irish and Chinese in Australia, Canada, and the United States, which began in earnest with the mid-nineteenth century gold rushes in California, New South Wales, Victoria, and British Columbia.