Access Provided by University of Queensland at 02/17/13 10:42PM GMT the Ridiculous Performance of Taylor Mac

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

César Alvarez Pronouns: They/Them [email protected]

César Alvarez pronouns: they/them [email protected] Representation: Rachel Viola [email protected] United Talent Agency !!! "eventh Ave. #th $loor %e& Yor() %Y *+*+, T: -*-..++./--0 EDUCATION -++1 2ard College, M$A Music/"ound -++/ 45erlin Conservatory) B3 Sa6ophone, Electronic) and Interdisciplinary Performance -++* Universidad de La Ha5ana) Cu5a) School for International Training) semester o: study *111 8nterlochen Arts Academy) High School Diploma w/ Honors AWARDS AND HONORS -+-+ Ne& Musical commissioned by Play&right's Horizons -+-+ Hermitage Fello& -+*8 Princeton Arts Fello& -+*! "undance Institute/Ucross Composer & Play&right Fello&ship -+*, ;ucille Lortel A&ard - Outstanding Musical - FUTURITY -+*, The American Theater Wing's Jonathan Larson A&ard -+*, Of-2road&ay Alliance A&ard - Best New Musical - FUTURITY -+*. Drama Des( Nomination – Outstanding Music in a Play - An Octoroon -+*0 7nsem5le Studio Theatre/"loan Commission - The Elementary Spacetime Show -+*/ =rama Des( Nomination – Outstanding Music in a Play - Good Person of Szechwan -+*- %7A Art Works Grant for FUTURITY at Soho Rep -+** %7A Art Works Grant for FUTURITY at American Repertory Theater -++4 Van Lier/3eet the Composer Fello& -++2 Composer at 9th Issue International Electro@Acoustic Music festival. Havana) Cu5a *111 <ispanic National Merit Scholar ONGOING PROJECTS -+*8 – Present The Potl c! – Music) Boo( and Lyrics. Commissioned by Barbara Whitman and Beth Ailliams -+*, - Present "OISE # Music) Boo( and Lyrics. Commissioned by The Pu5lic Theater and N'U/9lay&rights Horizons Theater School. Larson Legacy Concert at Adelphi University) Vineyard Arts ProFect. Upcoming: Workshop direc ed !" Sarah Benson% J&'" ()() -+*4 - Present The Elementary Spacetime Show D Music and Lyrics by César Alvarez. Boo( by César Alvarez and Emily Orling Directed 5y Sarah Benson. -

Craig Highberger Hattie Hathaway/Brian Butterick Jackie Dearest Pictures of Ethyl in My Head

Excerpt from When Jackie Met Ethyl / Curated by Dan Cameron, May 5 – June 1, 2016 © 2016 Howl! Arts, Inc. Excerpt from When Jackie Met Ethyl / Curated by Dan Cameron, May 5 – June 1, 2016 © 2016 Howl! Arts, Inc. Page 1 Page 1 Craig Highberger Hattie Hathaway/Brian Butterick Jackie Dearest Pictures of Ethyl in My Head Meeting Jackie Curtis during my first week at NYU Film School in 1973 and becoming his friend was one Ethyl Eichelberger, my sister, my mentor, my friend… of the most propitious things that has ever happened in my life. Knowing Jackie right after high school truly In 1986, I had the brilliant idea to do hardcore skinhead music matinees for all ages on Saturdays, at freed me, inspired my intellect, and opened my mind to possibilities I had never dreamed of. 3 p.m. at the Pyramid. Ethyl knew the club would be open early, so she came by to get ready for an early As Lily Tomlin and others clarified in my documentary, Jackie Curtis lived his life as performance art, show somewhere. I went down to the basement dressing room, when the club was packed, to talk to the rejecting conventional gender classification and shifting freely between female and male as he liked. One bands and there was Ethyl, surrounded by 25 somewhat homophobic skinhead boys with tattoos and day Jackie would be in James Dean mode, scruffy and unshaven, in blue denim and a t-shirt, with a pack bleachers who were enthralled by her and her makeup application. of Kools in one rolled-up sleeve. -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Presentation with Pomegranate Arts, Is the Last Time Taylor Mac Will Perform the Full 24-Hour Work in the U.S

Tweet it! Experience history like never before in #TaylorMac “A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC” at #PIFA2018 June 2 (Part I) and June 9 (Part II) at the @KimmelCenter. Tickets on sale now! More info @ kimmelcenter.org/pifa Press Contacts: Monica Robinson Rachel Goldman 215-790-5847 267-765-3712 [email protected] [email protected] KIMMEL CENTER ANNOUNCES LOCAL ARTISTS WHO WILL PERFORM WITH MACARTHUR GENIUS TAYLOR MAC IN MAC’S GROUNDBREAKING POP ODYSSEY A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC DURING THE 2018 PHILADELPHIA INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF THE ARTS Philadelphia Engagement, June 2 & 9 at the Kimmel Center, In A Co- Presentation with Pomegranate Arts, Is the Last Time Taylor Mac Will Perform the Full 24-Hour Work in the U.S. “ONE OF THE GREAT EXPERIENCES OF MY LIFE.” – THE NEW YORK TIMES “A MUST-SEE FOR ANYONE WHO WANTS TO SEE A KINDER, GENTLER SOCIETY.” – THE HUFFINGTON POST “THE COMMANDING MAC IS A GENUINE LEADER OF OUR TIMES.” – TIME OUT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, May 14, 2018) –– The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, in a co-presentation with Pomegranate Arts, is thrilled to announce the special guest artists who will perform in Taylor Mac’s ambitious, internationally acclaimed work A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC. Local Philadelphia performance artists and musicians will join Mac in these final U.S. performances of the full, 24-hour-long pop odyssey, June 2 & 9 at the Kimmel Center’s Merriam Theater, as part of the 2018 Philadelphia International Festival of the Arts (PIFA). Mac will perform A 24- DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC as two distinct 12-hour concerts, Saturday, June 2 (1776-1896) and Saturday, June 9 (1896-present day) — Mac’s longest continuous performances since the work premiered at St. -

THE MYSTERY of IRMA VEP Welcome

per ormances f at the OLD GLOBE ARENA STAGE AT THE JAMES S. COPLEY AUDITORIUM, SAN DIEGO MUSEUM OF ART AUGUST 2009 THE MYSTERY OF IRMA VEP Welcome UPCOMING Dear Friends, THE FIRST WIVES CLUB July 17 - Aug. 23, 2009 Welcome to an outrageous Old Globe Theatre evening of murder and mayhem on the moors! The Mystery of Irma Vep is a loving tribute to ❖❖❖ Victorian and gothic mystery, and a tour-de-force for our out- rageously talented actors, Jeffrey SAMMY M. Bender and John Cariani. Sep. 19 - Nov. 1, 2009 Charles Ludlam's enduring Old Globe Theatre masterpiece has had audiences rolling in the aisles for nearly three decades and I know this will be no exception. ❖❖❖ It is certainly the busiest time of the year for The Old Globe. We are presenting a total of five plays on our three stages. The Broadway- bound world premiere of The First Wives Club is currently playing in T H E SAVA N N A H the Old Globe Theatre. Music legends Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier DISPUTATION and Eddie Holland (Stop! In The Name of Love) have fashioned an Sep. 26 - Nov. 1, 2009 infectious score for this musical based on the popular film and book. The Old Globe Arena Stage at Get your tickets soon so you can say, “I saw it here first!” the James S. Copley Auditorium, The centerpiece of our summer season, as it has been for 75 years, is San Diego Museum of Art our Shakespeare Festival — currently in full swing with Twelfth Night, Cyrano de Bergerac and Coriolanus in repertory in the outdoor Festival Theatre. -

Contributors

Contributors Kelly Aliano received her PhD from the City University of New York Graduate Center. Her dissertation was entitled “Ridiculous Geographies: Mapping the Theatre of the Ridiculous as Radical Aesthetic.” She has taught at Hunter College and has stage-managed numerous productions throughout New York City. Patricia Badir has published on public space in medieval and Reformation dramatic entertainment in the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Exemplaria, and Theatre Survey. She also writes on religious iconography and postmedieval devotional writ- ing. She is the author of The Maudlin Impression: English Literary Images of Mary Magdalene, 1550–1700 (University of Notre Dame Press, 2009). She is currently working on playmaking and the perils of mimesis on Shakespeare’s stage and on Canadian Shakespeare in the first two decades of the twentieth century. This recent research has been published in Shakespeare Quarterly. Rosemarie K. Bank has published in Theatre Journal, Nineteenth- Century Theatre, Theatre History Studies, Essays in Theatre, Theatre Research International, Modern Drama, Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, Women in American Theatre, Feminist Rereadings of Modern American Drama, The American Stage, Critical Theory and Performance (both editions), Performing America, Interrogating America through Theatre and Performance, and Of Borders and Thresholds. She is the author of Theatre Culture in America, 1825– 1860 (Cambridge University Press, 1997) and is currently preparing Staging the Native, 1792–1892. A member of the College of Fellows of the American Theatre, a past fellow of the American Philosophical Society, and several times a fellow of the National Endowment for the Humanities, she was the editor of Theatre Survey from 2000 to 2003 and currently serves on several editorial boards. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

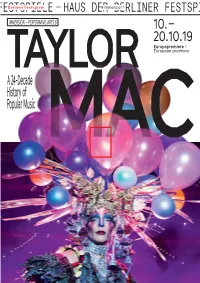

Programmheft Taylor Mac – a 24-Decade History of Popular Music

HAUS DER BERLINER FESTSPIELE — HAUS DER BERLINER FESTSPIELE Berliner Festspiele — HAUS DER#immersion BERLINER FESTSPIELE — HAUS DER BERLINER IMMERSION – PERFORMING ARTS 6 10. – 20.10.19 Europapremiere / European premiere A 24-Decade History of Popular Music I work in catharsis. That’s my job. Taylor Mac INHALT / CONTENTS 2 DAS KOSTBARE VOR- GEFÜHL EINER ANDEREN GEMEINSCHAFT / THE RARE P RESENTIMENT OF A DIFFERENT COMMUNITY Thomas Oberender 4 Chapter 1 1776–1836 10.10.19, 18:00–00:00 6 Chapter 2 1836–1896 12.10.19, 18:00–00:00 8 Chapter 3 1896–1956 18.10.19, 18:00–00:00 10 Chapter 4 1956–2019 20.10.19, 18:00–00:00 12 LASST UNS DIE QUEER- NESS UNSERER GE- SCHICHTE ENTDECKEN! / 22 LET’S UNEARTH THE QUEERNESS IN OUR HISTORY! Interview Taylor Mac & Dennis Pohl 30 KÜNSTLER*INNEN UND MITWIRKENDE / ARTISTS AND PERFORMERS 34 Biographien / biographies 40 Impressum / imprint 1 Das kostbare Vorgefühl einer anderen Gemeinschaft / The Rare Presentiment of a Different Community 24 Stunden, 24 Dekaden, 246 Songs. Aus der Perspek- 24 hours, 24 decades, 246 songs. Using newly tive einer Queer History erzählt Taylor Mac die arranged songs that have been popular in America Geschichte der Vereinigten Staaten anhand neu from 1776 to the present day, Taylor Mac tells the arrangierter Songs, die von 1776 bis heute in story of the United States from the perspective Amerika populär waren. „A 24-Decade History of of a queer history. “A 24-Decade History of Popular Popular Music“ thematisiert und befragt histori- Music” focuses on and queries historical events sche Ereignisse wie die Amerikanische Revolution such as the American Revolution and the Prohib- und die Prohibitionszeit, ebenso wie die AIDS- ition Period, as well as the AIDS crisis and the every- Krise oder den Alltag einer Hausfrau des 18. -

Cap Ucla Presents Taylor Mac's Holiday Sauce

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CAP UCLA PRESENTS TAYLOR MAC’S HOLIDAY SAUCE…PANDEMIC! CREATED BY MAC AND POMEGRANATE ARTS DECEMBER 12 COVID-Era Virtual Reinvention of the Beloved Annual Live Seasonal Variety Show Follows November 13 Release of Holiday Sauce Album On December 12, UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance (CAP UCLA) and prestigious theaters and cultural institutions around the world present the Pomegranate Arts production Taylor Mac’s Holiday Sauce…Pandemic! The special, live-streamed event reimagines for this time of social distancing Mac’s celebrated Holiday Sauce show. Holiday Sauce…Pandemic! is presented at 7 p.m. PST on December 12. The event requires a minimum donation of $25 to CAP UCLA to register. Mac dedicates Holiday Sauce to Mother Flawless Sabrina, Mac’s drag mother, who passed away three weeks before the live show made its world premiere at Town Hall NYC in December 2017. Conceived as a virtual vaudeville, Holiday Sauce…Pandemic! blends music, film, burlesque, and random acts of fabulousness. To create it, Mac has joined forces with longtime creative producer Pomegranate Arts (Linda Brumbach, Founder and Director; Alisa E. Regas, Managing Director, Creative), director Jeremy Lydic, designers Machine Dazzle and Anastasia Durasova, and cinematographer Rob Kolodny. It features a full band led music director/arranger Matt Ray and including Colin Brooks, Viva DeConcini, Antoine Drye, Greg Glassman, J. Walter Hawkes, Marika Hughes, Dana Lyn, and Gary Wang; special guests Thornetta Davis, Stephanie Christi’an, and Tigger! Ferguson; and performers who make cameo appearances: Dusty Childers, Sister Rosemary Chicken, sidhe degreene, Romeo-Jay Jacinto, Glenn Marla, Travis Santell Rowland (Qween), and Timothy White Eagle. -

University of Copenhagen Faculty of Humanities

Disincarnation Jack Smith and the character as assemblage Tranholm, Mette Risgård Publication date: 2017 Document version Other version Document license: CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Tranholm, M. R. (2017). Disincarnation: Jack Smith and the character as assemblage. Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN FACULTY OF HUMANITIES PhD Dissertation Mette Tranholm Disincarnation Jack Smith and the character as assemblage Supervisor: Laura Luise Schultz Submitted on: 26 May 2017 Name of department: Department of Arts and Cultural Studies Author(s): Mette Tranholm Title and subtitle: Disincarnation: Jack Smith and the character as assemblage Topic description: The topic of this dissertation is the American performer, photographer, writer, and filmmaker Jack Smith. The purpose of this dissertation is - through Smith - to reach a more nuanced understading of the concept of character in performance theater. Supervisor: Laura Luise Schultz Submitted on: 26 May 2017 2 Table of contents Acknowledgements.............................................................................................................................................................7 Overall aim and research questions.................................................................................................................................9 Disincarnation in Roy Cohn/Jack Smith........................................................................................................................13 -

Winter/Spring Season

WINTER/SPRING SEASON Jan 23–24 eighth blackbird Hand Eye __________________________________________ Jan 28–30 Toshiki Okada/chelfitsch God Bless Baseball __________________________________________ Feb 4 and 6–7 Ingri Fiksdal, Ingvild Langgård & Signe Becker Cosmic Body __________________________________________ Feb 11–14 Faye Driscoll Thank You For Coming: Attendance __________________________________________ Feb 18–27 Tim Etchells/Forced Entertainment The Notebook, Speak Bitterness, and (In) Complete Works: Table Top Shakespeare __________________________________________ Mar 5–6 Joffrey Academy of Dance Winning Works __________________________________________ Mar 25–26 eighth blackbird featuring Will Oldham (Bonnie “Prince” Billy) Ghostlight __________________________________________ Mar 31–Apr 3 Blair Thomas & Co. Moby Dick __________________________________________ Apr 7–10 Teatrocinema Historia de Amor (Love Story) __________________________________________ Apr 12 and 14–16 Taylor Mac A 24-Decade History of Popular Music __________________________________________ Apr 28–May 1 Kyle Abraham/ Abraham.In.Motion When the Wolves Came In Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Apr 12 and 14–16, 2016 FEATURING Vocals Taylor Mac ____________________________________________ A 24-Decade History WITH Music Director/Piano/ Matt Ray of Popular Music: Backup Vocals Bass Danton Boller Drums Bernice “Boom Boom” (1956–1986) Brooks ____________________________________________ Guitar Viva De Concini CONCEIVED, WRITTEN, PERFORMED, AND CODIRECTED BY Baritone -

Part 2 of the Interview with Minette

LadyLik Part-Time Lady... Full Time Queen Part 2 of the interview with Minette. be several centuries more before we see his like There is something eternal about Minette, the again. "The Ridiculous was reestablished a few years child performer in vaudeville who wasn't happy ago by Everett Quinton, Ludlam's long-time lover until she was a professional female impersonator. and co-star. The Ridiculous' current production of She starred in underground drag films by Ava-Graph Ludlam's The Mystery of Irma Vep is sold out for Studio and was the subject of a biography, Recollec- months in advance. tions of a Part-Time Lady. When we met her she To us Minette is legendary. And what becomes a hadn't performed in 20 years. In the last issue of legend most? Being with other legends. Minette has LadyLike we followed Minette's career from Phila- an eternal quality, illustrated by an incident years delphia to Providence through bars, clubs, show- after she stopped performing: "One time a boy rooms and carnival midways. This installment is all comes up to me and says, 'Weren't you Minette?' New York tales and the names in it are more familiar And I said, 'I still am.'" to LadyLike readers. After moving to New York Minette's circle grew Ms Bob: Tell me about the biography, Recollec- to include some of Manhattan's more influential tions of a Part-Time Lady. When was it published? gender interpreters. Of course, she continued to Minette: They had the publication party the 20th work with professional impersonators, like Harvey Lee and Pudgy Roberts.