Faye Driscoll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

César Alvarez Pronouns: They/Them [email protected]

César Alvarez pronouns: they/them [email protected] Representation: Rachel Viola [email protected] United Talent Agency !!! "eventh Ave. #th $loor %e& Yor() %Y *+*+, T: -*-..++./--0 EDUCATION -++1 2ard College, M$A Music/"ound -++/ 45erlin Conservatory) B3 Sa6ophone, Electronic) and Interdisciplinary Performance -++* Universidad de La Ha5ana) Cu5a) School for International Training) semester o: study *111 8nterlochen Arts Academy) High School Diploma w/ Honors AWARDS AND HONORS -+-+ Ne& Musical commissioned by Play&right's Horizons -+-+ Hermitage Fello& -+*8 Princeton Arts Fello& -+*! "undance Institute/Ucross Composer & Play&right Fello&ship -+*, ;ucille Lortel A&ard - Outstanding Musical - FUTURITY -+*, The American Theater Wing's Jonathan Larson A&ard -+*, Of-2road&ay Alliance A&ard - Best New Musical - FUTURITY -+*. Drama Des( Nomination – Outstanding Music in a Play - An Octoroon -+*0 7nsem5le Studio Theatre/"loan Commission - The Elementary Spacetime Show -+*/ =rama Des( Nomination – Outstanding Music in a Play - Good Person of Szechwan -+*- %7A Art Works Grant for FUTURITY at Soho Rep -+** %7A Art Works Grant for FUTURITY at American Repertory Theater -++4 Van Lier/3eet the Composer Fello& -++2 Composer at 9th Issue International Electro@Acoustic Music festival. Havana) Cu5a *111 <ispanic National Merit Scholar ONGOING PROJECTS -+*8 – Present The Potl c! – Music) Boo( and Lyrics. Commissioned by Barbara Whitman and Beth Ailliams -+*, - Present "OISE # Music) Boo( and Lyrics. Commissioned by The Pu5lic Theater and N'U/9lay&rights Horizons Theater School. Larson Legacy Concert at Adelphi University) Vineyard Arts ProFect. Upcoming: Workshop direc ed !" Sarah Benson% J&'" ()() -+*4 - Present The Elementary Spacetime Show D Music and Lyrics by César Alvarez. Boo( by César Alvarez and Emily Orling Directed 5y Sarah Benson. -

Presentation with Pomegranate Arts, Is the Last Time Taylor Mac Will Perform the Full 24-Hour Work in the U.S

Tweet it! Experience history like never before in #TaylorMac “A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC” at #PIFA2018 June 2 (Part I) and June 9 (Part II) at the @KimmelCenter. Tickets on sale now! More info @ kimmelcenter.org/pifa Press Contacts: Monica Robinson Rachel Goldman 215-790-5847 267-765-3712 [email protected] [email protected] KIMMEL CENTER ANNOUNCES LOCAL ARTISTS WHO WILL PERFORM WITH MACARTHUR GENIUS TAYLOR MAC IN MAC’S GROUNDBREAKING POP ODYSSEY A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC DURING THE 2018 PHILADELPHIA INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF THE ARTS Philadelphia Engagement, June 2 & 9 at the Kimmel Center, In A Co- Presentation with Pomegranate Arts, Is the Last Time Taylor Mac Will Perform the Full 24-Hour Work in the U.S. “ONE OF THE GREAT EXPERIENCES OF MY LIFE.” – THE NEW YORK TIMES “A MUST-SEE FOR ANYONE WHO WANTS TO SEE A KINDER, GENTLER SOCIETY.” – THE HUFFINGTON POST “THE COMMANDING MAC IS A GENUINE LEADER OF OUR TIMES.” – TIME OUT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, May 14, 2018) –– The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, in a co-presentation with Pomegranate Arts, is thrilled to announce the special guest artists who will perform in Taylor Mac’s ambitious, internationally acclaimed work A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC. Local Philadelphia performance artists and musicians will join Mac in these final U.S. performances of the full, 24-hour-long pop odyssey, June 2 & 9 at the Kimmel Center’s Merriam Theater, as part of the 2018 Philadelphia International Festival of the Arts (PIFA). Mac will perform A 24- DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC as two distinct 12-hour concerts, Saturday, June 2 (1776-1896) and Saturday, June 9 (1896-present day) — Mac’s longest continuous performances since the work premiered at St. -

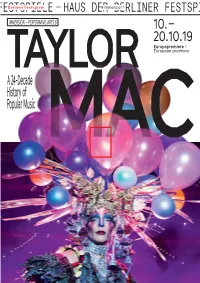

Programmheft Taylor Mac – a 24-Decade History of Popular Music

HAUS DER BERLINER FESTSPIELE — HAUS DER BERLINER FESTSPIELE Berliner Festspiele — HAUS DER#immersion BERLINER FESTSPIELE — HAUS DER BERLINER IMMERSION – PERFORMING ARTS 6 10. – 20.10.19 Europapremiere / European premiere A 24-Decade History of Popular Music I work in catharsis. That’s my job. Taylor Mac INHALT / CONTENTS 2 DAS KOSTBARE VOR- GEFÜHL EINER ANDEREN GEMEINSCHAFT / THE RARE P RESENTIMENT OF A DIFFERENT COMMUNITY Thomas Oberender 4 Chapter 1 1776–1836 10.10.19, 18:00–00:00 6 Chapter 2 1836–1896 12.10.19, 18:00–00:00 8 Chapter 3 1896–1956 18.10.19, 18:00–00:00 10 Chapter 4 1956–2019 20.10.19, 18:00–00:00 12 LASST UNS DIE QUEER- NESS UNSERER GE- SCHICHTE ENTDECKEN! / 22 LET’S UNEARTH THE QUEERNESS IN OUR HISTORY! Interview Taylor Mac & Dennis Pohl 30 KÜNSTLER*INNEN UND MITWIRKENDE / ARTISTS AND PERFORMERS 34 Biographien / biographies 40 Impressum / imprint 1 Das kostbare Vorgefühl einer anderen Gemeinschaft / The Rare Presentiment of a Different Community 24 Stunden, 24 Dekaden, 246 Songs. Aus der Perspek- 24 hours, 24 decades, 246 songs. Using newly tive einer Queer History erzählt Taylor Mac die arranged songs that have been popular in America Geschichte der Vereinigten Staaten anhand neu from 1776 to the present day, Taylor Mac tells the arrangierter Songs, die von 1776 bis heute in story of the United States from the perspective Amerika populär waren. „A 24-Decade History of of a queer history. “A 24-Decade History of Popular Popular Music“ thematisiert und befragt histori- Music” focuses on and queries historical events sche Ereignisse wie die Amerikanische Revolution such as the American Revolution and the Prohib- und die Prohibitionszeit, ebenso wie die AIDS- ition Period, as well as the AIDS crisis and the every- Krise oder den Alltag einer Hausfrau des 18. -

Cap Ucla Presents Taylor Mac's Holiday Sauce

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CAP UCLA PRESENTS TAYLOR MAC’S HOLIDAY SAUCE…PANDEMIC! CREATED BY MAC AND POMEGRANATE ARTS DECEMBER 12 COVID-Era Virtual Reinvention of the Beloved Annual Live Seasonal Variety Show Follows November 13 Release of Holiday Sauce Album On December 12, UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance (CAP UCLA) and prestigious theaters and cultural institutions around the world present the Pomegranate Arts production Taylor Mac’s Holiday Sauce…Pandemic! The special, live-streamed event reimagines for this time of social distancing Mac’s celebrated Holiday Sauce show. Holiday Sauce…Pandemic! is presented at 7 p.m. PST on December 12. The event requires a minimum donation of $25 to CAP UCLA to register. Mac dedicates Holiday Sauce to Mother Flawless Sabrina, Mac’s drag mother, who passed away three weeks before the live show made its world premiere at Town Hall NYC in December 2017. Conceived as a virtual vaudeville, Holiday Sauce…Pandemic! blends music, film, burlesque, and random acts of fabulousness. To create it, Mac has joined forces with longtime creative producer Pomegranate Arts (Linda Brumbach, Founder and Director; Alisa E. Regas, Managing Director, Creative), director Jeremy Lydic, designers Machine Dazzle and Anastasia Durasova, and cinematographer Rob Kolodny. It features a full band led music director/arranger Matt Ray and including Colin Brooks, Viva DeConcini, Antoine Drye, Greg Glassman, J. Walter Hawkes, Marika Hughes, Dana Lyn, and Gary Wang; special guests Thornetta Davis, Stephanie Christi’an, and Tigger! Ferguson; and performers who make cameo appearances: Dusty Childers, Sister Rosemary Chicken, sidhe degreene, Romeo-Jay Jacinto, Glenn Marla, Travis Santell Rowland (Qween), and Timothy White Eagle. -

Winter/Spring Season

WINTER/SPRING SEASON Jan 23–24 eighth blackbird Hand Eye __________________________________________ Jan 28–30 Toshiki Okada/chelfitsch God Bless Baseball __________________________________________ Feb 4 and 6–7 Ingri Fiksdal, Ingvild Langgård & Signe Becker Cosmic Body __________________________________________ Feb 11–14 Faye Driscoll Thank You For Coming: Attendance __________________________________________ Feb 18–27 Tim Etchells/Forced Entertainment The Notebook, Speak Bitterness, and (In) Complete Works: Table Top Shakespeare __________________________________________ Mar 5–6 Joffrey Academy of Dance Winning Works __________________________________________ Mar 25–26 eighth blackbird featuring Will Oldham (Bonnie “Prince” Billy) Ghostlight __________________________________________ Mar 31–Apr 3 Blair Thomas & Co. Moby Dick __________________________________________ Apr 7–10 Teatrocinema Historia de Amor (Love Story) __________________________________________ Apr 12 and 14–16 Taylor Mac A 24-Decade History of Popular Music __________________________________________ Apr 28–May 1 Kyle Abraham/ Abraham.In.Motion When the Wolves Came In Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Apr 12 and 14–16, 2016 FEATURING Vocals Taylor Mac ____________________________________________ A 24-Decade History WITH Music Director/Piano/ Matt Ray of Popular Music: Backup Vocals Bass Danton Boller Drums Bernice “Boom Boom” (1956–1986) Brooks ____________________________________________ Guitar Viva De Concini CONCEIVED, WRITTEN, PERFORMED, AND CODIRECTED BY Baritone -

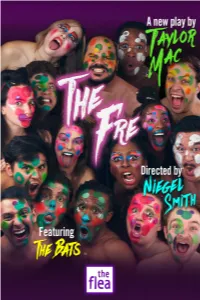

The-Fre-Program-2.Pdf

THE FLEA THEATER NIEGEL SMITH, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OSTROW, PRODUCING DIRECTOR PRESENTS THE WORLD PREMIERE OF THE FRE BY TAYLOR MAC DIRECTED BY NIEGEL SMITH FEATURING THE BATS RYAN CHITTAPHONG, GEORGIA KATE COHEN, JON EDWARD COOK, ADAM COY, JOSEPH DALFONSO, NATE DECOOK, URE EGBUHO, JOAN MARIE, ALEX J. MORENO, MARCUS JONES, DRITA KABASHI, MATTHEW MACCA, CESAR MUNOZ, YVONNE JESSICA PRUITT, SARAH ALICE SHULL, LAMBERT TAMIN JIAN JUNG SCENIC DESIGNER MACHINE DAZZLE COSTUME DESIGNER XAVIER PIERCE LIGHTING DESIGNER MATT RAY COMPOSER, MUSIC DIRECTOR & SOUND DESIGNER SARAH EAST JOHNSON CHOREOGRAPHER ADAM J. THOMPSON VIDEO DESIGNER KRISTAN SEEMEL AssOCIATE DIRECTOR SOOA KIM AssOCIATE VIDEO DESIGNER REBECCA APARCIO & SARAH JANE SCHOSTACK AssISTANT DIRECTORS CORI WILLIAMS AssISTANT SCENIC DESIGNER & PROPERTIES DESIGNER HALEY GORDON PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER CAST Hero............................................Ryan Chittaphong / Lambert Tamin Frankie Fre ..................................... Joseph Dalfonso / Alex J. Moreno Taylor Fre..................................Drita Kabashi / Yvonne Jessica Pruitt Maggie Fre..............................Geogia Kate Cohen / Sarah Alice Shull Bobby Fre (Frankie Fre U/S) ...........................................Nate DeCook Bobby Fre (Hero U/S) .....................................................Cesar Munoz Billy Fre ................................................Jon Edward Cook / Adam Coy Franny Fre ...................................................Ure Egbuho / Joan Marie Brody Fre ..........................................Matthew -

A 24-Decade History

THE FLEA THEATER NIEGEL SMITH ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OSTROW PRODUCING DIRECTOR presents A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC: 1776-1836: WORK IN PROGRESS Conceived, written, performed and co-directed by TAYLOR MAC Music Director/Piano/Backing Vocals Co-Director MATT RAY NIEGEL SMITH Costume Designer Dramaturg MACHINE DAZZLE JOCELYN CLARKE Associate Producer Associate Producer KALEB KILKENNY ALISA E. REGAS Executive Producer LINDA BRUMBACH Co-Produced by POMEGRANATE ARTS AND NATURE’S DARLINGS A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC is commissioned in part by Carole Shorenstein Hays, The Curran SF; Carolina Performing Arts, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA; Hancher Auditorium at the University of Iowa; Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts; Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; New Haven Festival of Arts & Ideas; New York Live Arts; OZ Arts Nashville; University Musical Society of the University of Michigan. This work was developed with the support of the Park Avenue Armory residency program and the 2015 Sundance Institute Theatre Lab at the Sundance Resort. A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC was made possible with funding by the New England Foundation for the Arts’ National Theater Project, with lead funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. BRIAN ALDOUS LIGHTING DESIGN MILES POLASKI SOUND DESIGN LILLY WEST SOUND ENGINEER MICHAL MENDELSON STAGE MANAGER FEATURING TAYLOR MAC, Vocals with Matt Ray, Music Director/Piano/Backing Vocals Bernice “Boom Boom” Brooks, Drums Viva De -

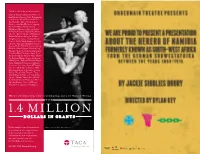

We Are Proud Program.Pages

RBMM JOB #: 3BON140002_TACA Playbill 2014 ad_01 AD SIZE: 4.625" x 7.75" PLAYBILL TRIM 5.375" x 8.5" CLIENT: TACA LIVE: - PUB: Playbill BLEED: non RELEASE DATE: 02/03/14 COLOR: CMYK FOR QUESTIONS CALL: Julie Ramirez (214.987.6500) 2014 TACA B ENEFIC I A RIES African American Repertory Theater Arts District Chorale • AT&T Performing Arts Center • Avant Chamber Ballet Big Thought • Bruce Wood Dance Project • Cara Mia Theatre Company Chamber Music International Children’s Chorus of Greater Dallas Dallas Bach Society • Dallas Black Dance Theatre • Dallas Chamber Symphony Dallas Children’s Theater • Dallas Symphony Orchestra • Dallas Theater Center • Dallas Wind Symphony • Echo Theatre • Fine Arts Chamber Players Greater Dallas Youth Orchestra • Irving Chorale • Junior Players • Kitchen Dog Theater • Lone Star Circus Arts Center Lone Star Wind Orchestra • Lyric Stage Nasher Sculpture Center • One Thirty Productions Matinee Series • Orchestra of New Spain • Orpheus Chamber Singers Plano Symphony Orchestra • Sammons Center for the Arts • Second Thought Theatre • Shakespeare Dallas • SMU Meadows School of the Arts • Teatro Dallas • Texas Ballet Theater • Texas Winds Musical Outreach • The Dallas Opera • Theatre Three, Inc. • TITAS Turtle Creek Chorale • Undermain Theatre Uptown Players • Voices of Change WaterTower Theatre • WordSpace We’re supporting the performing arts in North Texas with 1.4 M I L L ION DOLLARS IN GRANTS TACA champions artistic excellence Photo courtesy of Texas Ballet Theater in performing arts organizations and encourages innovation, collaboration, and engagement through financial support, stewardship, and resources. A STAGED READING 214.520.3930 taca-arts.org 3BON140002 Playbill ad 2014_NoBleed_4n625x7n75_02ef.indd 1 2/4/14 12:25 PM Thank you to our donors that support Undermain’s mission and make it About Jackie Sibblies Drury possible to bring affordable, professional theatre to Dallas! Jackie Sibblies Drury is a Brooklyn-based Corporations, Foundations, Organizations, playwright. -

Access Provided by University of Queensland at 02/17/13 10:42PM GMT the Ridiculous Performance of Taylor Mac

Access Provided by University of Queensland at 02/17/13 10:42PM GMT The Ridiculous Performance of Taylor Mac Sean F. Edgecomb Taylor Mac is a contemporary actor and playwright who carries on the tradition of the Ridiculous Theatre for the twenty-first century. After solidifying his reputation as an actor in the 1990s, Mac became aware of the first-wave Ridiculous canon of Jack Smith, Ronald Tavel, and Ethyl Eichelberger and immersed himself in the works of Charles Ludlam. Ludlam, considered by many to be the seminal Ridiculous auteur, developed the Ridiculous form by writing, directing, and appearing in twenty-nine original plays for his Ridiculous Theatrical Company (RTC) between its founding in 1967 and his untimely death in 1987. Ludlam’s Ridiculous aesthetic juxtaposed the modernist tradition of the avant-garde with camp, clowning, and drag. Forming within the gay community at the watershed of gay liberation, it was one of the first fully realized queer theatre forms in the United States. More specifically, it mixed high literary culture with low pop culture, generating a pastiche that reflected and satirized contemporary society.1 Farcical in nature, the Ridiculous contributed to the emergence of the postmodern clown,2 a comic figure who appropriates traditional clowning skills and “fragments, subverts and inverts” them to create a self-reflexive and deconstruc- tive performance.3 By layering Ludlam’s clown (an entertainer combining traditional Sean F. Edgecomb is the director of the Bachelor of Creative Arts and a lecturer in drama at the Uni- versity of Queensland in Australia. His primary research interests are queer performance, queer theory, and theatre for social change, with a particular focus on the construction and cultural dissemination of LGBTQ history. -

TAYLOR MAC Nature’S Darlings, LLC, 32 Gramercy Park South, #3C, New York, NY 10003 Email: [email protected]; Telephone: 646-853-5305

TAYLOR MAC www.taylormac.org Nature’s Darlings, LLC, 32 Gramercy Park South, #3C, New York, NY 10003 Email: [email protected]; Telephone: 646-853-5305 Production History (2005 to 2015 of works written by Taylor Mac) A 24-Decade History of Popular Music • New York Live Arts, 2015 • Lincoln Center, 2014, 2013 and 2012 • The Public Theater, Newman Theater, Under the Radar Festival, 2013 • The Arches, Glasgow, 2013 • Dublin Fringe, Ireland, 2013 • Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 2013 • Australian Tour (Melbourne Recital Hall, Darwin Festival, Brisbane Powerhouse, Lismore’s NORPA), 2013 • Fischer Center, Bard College, 2013 • Joe’s Pub, New York City, 2012, 2013, and 2014 Hir • Playwrights Horizons, New York premiere, 2015 • Mixed Blood Theater, Minneapolis, 2015 • Magic Theatre, San Francisco, world-premiere, 2014 The Last Two People On Earth, An Apocalyptic Vaudeville • Devised by Taylor Mac, Mandy Patinkin, Susan Stroman & Paul Ford, • Performed by Taylor Mac and Mandy Patinkin • Directed by Susan Stroman • American Repertory Theater, 2015 • Classic Stage Company, New York, 2013 The Walk Across America For Mother Earth • Premiere co-production between La Mama and The Talking Band, 2011 The Lily’s Revenge • American Repertory Theater, 2012 • Southern Repertory, New Orleans, 2012 • The Magic Theater, Spring of 2011 • HERE Arts Center, NYC, Fall of 2009 Comparison is Violence (solo-concert of covers) • 2011 Australian/NZ Tour to: Sydney Opera House, Brisbane Powerhouse, Perth Arts Festival, Melbourne Recital Center, & Auckland Arts Festival -

Late Winter 2019 at Seattle Theatre Group

NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2019 The Bellevue Collection Shop. Sip & Celebrate at The Collection. Make your holidays memorable. Enjoy the magic of the nightly Snowfl ake Lane parade with falling snow and festive music. Shop over 200 stores, explore an expansive Dining District and delight in extended holiday shopping hours with free parking—All in One Place. bellevuecollection.com THE BELLEVUE COLLECTION BELLEVUE SQUARE • BELLEVUE PLACE • LINCOLN SQUARE Located between NE 4th and NE 8th on Bellevue Way. 425-454-8096 Untitled-8 1 11/5/19 12:04 PM November/December 2019 | Volume 16, No. 2 WELCOMEFrom Seattle Theatre Group, a non-profit arts organization Welcome! As we continue our 2019/2020 Performing Arts Season, we close out a memorable year with a lineup of performances featuring musicians and dancers of the highest caliber, as well as entertaining productions that are fun for the entire family! First up is Love Heals All Wounds, which we present for one night only at Cornish Playhouse at Seattle Center, featuring the intricate and urban choreography of Jon Boogz and Lil Buck, the stirring message of spoken word artist Robin Sanders, and an all-star cast of movement artists. Focusing on the issues of climate change, mass incarceration, and immigration, this piece addresses the wave of questioning and criticism that has cast a wide shadow over real, everyday obstacles that have plagued our communities for decades. On November 21, we honor one of the most influential jazz labels of all time with the Blue Note Records 80th Birthday Celebration. Featuring performances by vocalist/pianist Kandace Springs, James Carter Organ PAUL HEPPNER President Trio, and pianist James Francies and his trio, this evening will offer a MIKE HATHAWAY Senior Vice President spectacular celebration of the iconic label, as well as jazz music today. -

Taylor Mac a 24-Decade History of Popular Music (Abridged) Saturday, April 28, 2018 7:30 Pm

Taylor Mac A 24-Decade History of Popular Music (Abridged) Saturday, April 28, 2018 7:30 pm Photo: © Ian Douglass 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. HANCHER AUDITORIUM PRESENTS TAYLOR MAC A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC (ABRIDGED) Conceived, written, performed, and co-directed by TAYLOR MAC Music Director / Arranger Costume Designer MATT RAY MACHINE DAZZLE Executive Producer LINDA BRUMBACH Associate Producer ALISA E. REGAS Co-Produced by POMEGRANATE ARTS and NATURE’S DARLINGS A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC is commissioned in part by Hancher Auditorium at the University of Iowa; ASU Gammage at Arizona State University; Belfast International Arts Festival and 14 - 18 NOW WW1 Centenary Art Commissions; Carole Shorenstein Hays, The Curran SF; Carolina Performing Arts, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA; Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts; Melbourne Festival; Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; International Festival of Arts & Ideas (New Haven); New York Live Arts; OZ Arts Nashville; Stanford Live at Stanford University; University Musical Society of the University of Michigan. This work was developed with the support of the Park Avenue Armory residency program, MASS MoCa (Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art), New York Stage and Film & Vassar’s Powerhouse Theater, and the 2015 Sundance Institute Theatre Lab at the Sundance Resort with continuing post- lab dramaturgical support through its initiative with the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. A 24-DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC was made possible with funding by the New England Foundation for the Arts' National Theater Project, with lead funding from The Andrew W.