Humorous Assaults on Patriarchal Ideology*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing & Journalism

140 Writing & Journalism Enroll at uclaextension.edu or call (800) 825-9971 Reg# 375735 Fee: $399 Writers’ Program No refund after 10 Nov. WRITING & ❖ Remote Instruction 6 mtgs Tuesday, 7-10pm, Oct. 27-Dec. 1 Creative Writing Enrollment limited to 15 students. c For help in choosing a course or determining if a Rachel Kann, MFA, author of the collection 10 for course fulfills certificate requirements, contact the Everything. Ms. Kann is an award-winning poet whose Writers’ Program at (310) 825-9415. work has appeared in various anthologies, including JOURNALISM Word Warriors: 35 Women Leaders in the Spoken Word Revolution. She is the recipient of the UCLA Extension Basics of Writing Outstanding Instructor Award for Creative Writing. These basic creative writing courses are for WRITING X 403 students with no prior writing experience. Finding Your Story Instruction is exercise-driven; the process of 2.0 units workshopping—in which students are asked to The scariest part of writing is staring at that blank page! share and offer feedback on each other’s work This workshop is for anyone who has wanted to write but with guidance from the instructor—is introduced. doesn’t know where to start or for writers who feel stuck Please call an advisor at (310) 825-9415 to deter- and need a new form or jumping off point for unique mine which course will best help you reach your story ideas. The course provides a safe, playful atmo- writing goals. sphere to experiment with different resources for stories, such as life experiences, news articles, interviews, his- WRITING X 400 tory, and mythology. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Hattie Winston Wheeler

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Hattie Winston Wheeler Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Winston, Hattie Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Hattie Winston Wheeler, Dates: October 7, 2005 Bulk Dates: 2005 Physical 5 Betacame SP videocasettes (2:17:53). Description: Abstract: Actress Hattie Winston (1945 - ) has been recognized with an Obie Award, among other honors. Winston's theatre credits include, "Hair," "The Tap Dance Kid," and, "To Take Up Arms." Her television and film credits include, "Jackie Brown," "Becker," and, "True Crime." Wheeler was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on October 7, 2005, in Encino, California. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2005_237 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Actress Hattie Mae Winston was born in Lexington, Mississippi, on March 3, 1945, to Selena Thurmond Winston and Roosevelt Love Winston. Winston was raised by her grandmother, Cora Thurmond, in nearby Greenville, Mississippi. Attending Washington Irving High School in New York City, Winston graduated in 1963; throughout her academic career she was an accomplished student and an exceptionally talented vocalist. Winston attended Howard University in Washington, D.C. after receiving a full voice scholarship. Winston moved back to New York City after one year at Howard and enrolled in an actor’s group study workshop; success came quickly. In 1968, Winston became a replacement performer in Hair, in 1969 obtained a part in Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie?, and in 1970 was cast in The Me Nobody Knows, all of which were significant Broadway roles. -

The Lumberjack Folding Five

m&k The Lumberjack For the week of Jan. 7-13 Folding five The Ben Folds Five trio will be stopping by to perform Feb. 9 at Club Rio in Scottsdale. Dance Hall Punk band The Dance Hall Crashers is com ing in Febuary to Gibson’s in Tempe. lext Is The Man, The Myth, The Ghost. Space Ghost. I Inside this - „ w e e k : A look at 1998 • I ¥ h t tp:/fwvm.t hejac k.nau.edu/happc n i n gs V S STORY VIES Jackie Brown *** Rainmaker ***1/2 I think Quentin Tarantino For a lawyer turned writer, might be a one-trick pony. John Grisham has turned into Granted, that one trick is fun quite a little movie machine. to watch, but if all you can do All of his legal thrillers have back on 1997 S is re-rnake “Pulp Fiction," been turned into movies, you’ll lose the casual audi ^ome even before they’ve Ahh, what a year. L o o k in g could it? ence. Samuel Jackson is great, been written. Where Michael back, we here at Happenings Most likely to be on future and Pam Grier does a pretty Crichtonks movies block decided to compile a year episodes of “C.O.P.S”: Rob Harkins 11 good job, but Robert De Niro buster, Grisham’s movies get book and look at what the ert Downey Ir. and Christian is miscast and Bridget Fonda more critical acclaim, which stars of 97 may be looking for Slater. Firestorm <r> is out of place. -

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, and NOWHERE: a REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS by G. Scott Campbell Submitted T

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS BY G. Scott Campbell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chairperson Committee members* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* Date defended ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for G. Scott Campbell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS Committee: Chairperson* Date approved: ii ABSTRACT Drawing inspiration from numerous place image studies in geography and other social sciences, this dissertation examines the senses of place and regional identity shaped by more than seven hundred American television series that aired from 1947 to 2007. Each state‘s relative share of these programs is described. The geographic themes, patterns, and images from these programs are analyzed, with an emphasis on identity in five American regions: the Mid-Atlantic, New England, the Midwest, the South, and the West. The dissertation concludes with a comparison of television‘s senses of place to those described in previous studies of regional identity. iii For Sue iv CONTENTS List of Tables vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Mid-Atlantic 28 3. New England 137 4. The Midwest, Part 1: The Great Lakes States 226 5. The Midwest, Part 2: The Trans-Mississippi Midwest 378 6. The South 450 7. The West 527 8. Conclusion 629 Bibliography 664 v LIST OF TABLES 1. Television and Population Shares 25 2. -

Queen Sugar” Biographies

“QUEEN SUGAR” BIOGRAPHIES AVA DUVERNAY CREATOR/WRITER/DIRECTOR/EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Award-winning filmmaker Ava DuVernay is the creator and executive producer of “Queen Sugar.” She directed the first two episodes and wrote the premiere and finale episodes of season one. Nominated for two Academy Awards and four Golden Globes, DuVernay’s feature "Selma" was one of 2015's most critically acclaimed films. Winner of the 2012 Sundance Film Festival's Best Director Prize for her previous feature "Middle of Nowhere," DuVernay's earlier directorial work includes "I Will Follow," "Venus Vs," "My Mic Sounds Nice" and "This is The Life." DuVernay is currently directing Disney’s “A Wrinkle in Time” based on the beloved children’s novel of the same name; this marks the first time an African American woman has directed a feature with a budget over $100 million. Her commitment to activism and reform will soon be seen in the criminal justice documentary “13th,” which has the honor of opening the New York Film Festival before premiering on Netflix. In 2010, she founded ARRAY, a distribution collective for filmmakers of color and women, named one of Fast Company’s Most Innovative Companies in Hollywood 2016. DuVernay was born and raised in Los Angeles, California. OPRAH WINFREY EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Oprah Winfrey is executive producer of OWN’s new drama series “Queen Sugar.” Winfrey is a global media leader, philanthropist, producer and actress. She has created an unparalleled connection with people around the world for nearly 30 years, making her one of the most respected and admired people today. As Chairman and CEO, she's guiding her successful cable network, OWN: Oprah Winfrey Network, and is the founder of O, The Oprah Magazine and Harpo Films. -

Squad Script

Squad by Troy Oates FADE IN: EXT. FOOTPATH - NIGHT Only small fragments are shown. Feet pounding against the pavement. Hair bouncing up and down against a forehead. Hands moving with the movement of the body. A gun tucked away in the side of the belt, comfortably sitting in its holster. For all that's shown, this person could be jogging. Eyes, determined on their goal. Never moving off centre for even a split second. They belong to RYAN EDWARDS A 37 year old man with short black hair head and a short beard to match. His current wardrobe consists of a grey T- shirt with a jacket over the top and black jeans. He's running, as fast as he can. It almost seems like he's gliding along this sidewalk. He's chasing RICKY ROBERTS a big oaf-ish sized man with buzz-cut blonde hair. EXT. PARK - NIGHT As they enter a park that's empty, Ricky comes to a small, square statue about waist high on him. He stumbles around it, slowing down for a split second, but this second is all Ryan needs to catch up to him. Ryan jumps up onto the statue, and then leaps down, a small step behind Ricky. Ryan extends both arms out and shoves Ricky in the back hard. From the force of the push, and the uneven terrain that he's running on, Ricky looses his footing, and skids to his knees, falling on his front. Ryan stops almost instantaneously. He stands over Ricky, reaching into the back of his belt for the handcuffs that rest there. -

Ribbons Show Community Support Former Editor Launches Horticulture Quarterly

'4- - \ / CDICU f li-J Crab fever „ page 12 Week of April .10-16, 2003 SANIBEL & CAPTIVA, FLORIDA VOLUME 30, NUMBER 15, 24 PAGES 75 CENTS : TIE NEVtt Ribbons show Former editor launches SWA concerned by irrigation community horticulture quarterly Some homes using 100,000 gallons or more per month support —See page 2 By Kate Thompson Staff writer Sanibel residents and visitors are tying traditional yel- low ribbons. The Sanibel Fire Control District's building on Palm Ridge Road is sporting some new yellow ribbons; so are their trucks. Chocolate shop "It was because of Sept. 11 and how much all the troops and civilians showed support for fire departments, proposed for because we lost so many firefighters that day," said Chief Sanibel Square Rich Dickerson. "This is a way for us to show support back to our troops." Planning Commission to The ribbons were the idea of Mary Hickey, assistant make final decision in administrator at the Sanibel Fire Control District, who two weeks made the ribbons which now are in place. And at Shell Net in the Bailey's Center, customers are —See page 2 getting into the act with an upside down tree. photo by Saul Taffet Set RIBBONS Ron Sympson shows off his controlled jungle. page 2 By Amy Fleming writing talent. After penning gardening 1 1 . > > Staff writer columns for several newspapers, publish- ing a gardening guide was a natural next The crustacean Gardeners of all skill levels, lovers of step. spirits of the all that is green and growing, there is Ron Sympson's South Florida beacfi hnally a gardening quarterly written just Gardening Guide is written in the same lOl sOllill 1 liMijltlll . -

Copyright by Lauren Elizabeth Wilks 2019

Copyright by Lauren Elizabeth Wilks 2019 The Thesis Committee for Lauren Elizabeth Wilks Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Thesis: Teens of Color on TV: Charting Shifts in Sensibility and Approaches to Portrayals of Black Characters in American Serialized Teen Dramas APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Mary Beltrán, Supervisor Alisa Perren Teens of Color on TV: Charting Shifts in Sensibility and Approaches to Portrayals of Black Characters in American Serialized Teen Dramas by Lauren Elizabeth Wilks Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 Abstract Teens of Color on TV: Charting Shifts in Sensibility and Approaches to Portrayals of Black Characters in American Serialized Teen Dramas Lauren Elizabeth Wilks, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2019 Supervisor: Mary Beltrán Over the past several decades, the serialized teen drama genre on television has moved through a series of cycles. The genre, which began with the arrival of Beverly Hills, 90210 (1990) on Fox Broadcasting Network, focuses on portrayals of different subsets of teenagers in their school, family and interpersonal lives. Sometimes called the “teen soap opera,” the genre is subject to the scrutiny and dismissiveness often reserved for media located in the realm of women’s entertainment. Through comparative discourse and textual analysis bounded in socio-cultural consideration of each temporal cycle, this thesis asserts that close attention to this genre can valuably articulate approaches to racial representational strategies. -

The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – the Touring Years

1 THE BEATLES: EIGHT DAYS A WEEK – THE TOURING YEARS Release Dates U.S. Theatrical Release September 16 SVOD September 17 U.K., France and Germany (September 15). Australia and New Zealand (September 16) Japan (September 22) www.thebeatleseightdaysaweek.com #thebeatleseightdaysaweek Official Twitter handle: @thebeatles Facebook: facebook.com/thebeatles YouTube: youtube.com/thebeatles Official Beatles website: www.thebeatles.com PREFACE One of the prospects that drew Ron Howard to this famous story was the opportunity to give a whole new generation of people an insightful glimpse at what happened to launch this extraordinary phenomenon. One generation – the baby boomers - had a chance to grow up with The Beatles, and their children perhaps only know them vicariously through their parents. As the decades have passed The Beatles are still as popular as ever across all these years, even though many of the details of this story have become blurred. We may assume that all Beatles’ fans know the macro-facts about the group. The truth is, however, only a small fraction are familiar with the ins and outs of the story, and of course, each new generation learns about The Beatles first and foremost, from their music. So, this film is a chance to reintroduce a seminal moment in the history of culture, and to use the distance of time, to give us the chance to think about “the how and the why” this happened as it did. So, while this film has a lot of fascinating new material and research, first and foremost, it is a film for those who were “not there”, especially the millennials. -

Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Theses & Dissertations CGU Student Scholarship Fall 2019 A Matter of Life and Def: Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry Anthony Blacksher Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Africana Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Poetry Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Television Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Blacksher, Anthony. (2019). A Matter of Life and Def: Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry. CGU Theses & Dissertations, 148. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd/148. doi: 10.5642/cguetd/148 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Matter of Life and Def: Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry By Anthony Blacksher Claremont Graduate University 2019 i Copyright Anthony Blacksher, 2019 All rights reserved ii Approval of the Dissertation Committee This dissertation has been duly read, reviewed, and critiqued by the Committee listed below, which hereby approves the manuscript of Anthony Blacksher as fulfilling the scope and quality requirements for meriting the degree of doctorate of philosophy in Cultural Studies with a certificate in Africana Studies. -

TV Guide an F28 Page ? & ? (Page 1)

ALMAGUIN NEWS, Wednesday, January 9, 2008 — Page 5 Thurs., Jan. 10 Thurs., Jan. 10 Thurs., Jan. 10 Thurs., Jan. 10 Fri., Jan. 11 Fri., Jan. 11 Sat., Jan. 12 Sat., Jan. 12 Sat., Jan. 12 Sun., Jan. 13 6:00 PM (6)(10)(21)(53) JEOP- (39) DISASTER DIY 11:30 PM (48) +++ MOVIE (58) TRADERS (7) LE TÉLÉJOURNAL (51)(52) AMERICAN (58) DIVINE LIFE (19) BILL MOYERS’ (2)(6) TRACEY (43) +++ (3)(7) ENT. TONIGHT (8) ARDY MOVIE Dead Silence (1996) 10:30 PM WONDER CHOUX IDOL REWIND 11:45 PM JOURNAL MCBEAN [9] CATHERINE Peaceful Warrior (2006) CANADA 7:30 PM (9)(8)(4)[9] SATUR- (53) +++ MOVIE (20)(51)(58) PAID (3)(7)(6)(10)(12)(19) (6)(10) (2)(6) FILM 101 (2)(6) THE INTER- (7) INFOMAN (48) +++ MOVIE CTV NEWS (3)(7)(20) ENT. (16) DAY REPORT Dumb and Dumber PROGRAM (20)(23) NEWS (9)(8)(4)[9] [9] AVOCAT DU DIA- GUNDAM SEED (13) VIEWS (21) WHO DO Paths of Glory (1957) TONIGHT DESTINY FAMILY GUY (1994) (7) CINÉMA Alamo CONSUMER (5)(3)(9)(8)(4)[9](14) YOU THINK (49) HANNAH MON- BLE (5)(3) DEGRASSI: (16) PRANK PATROL (58) TRUTH, DUTY, SHOWCASE (21) (8) (17)(51) TWO AND A (2004) NEWS (12) ACCESS HOLLY- TANA PRESSERE- NEXT GEN. Part 2 of 2 (19) LAWRENCE VALOUR (48) + (28) RICKY SPROCK- (7) LE TÉLÉJOURNAL (50) BELLE.COM HALF MEN MOVIE Story- WOOD B.D. SPORTS from Jan 10 (34) FRASIER WELK SHOW 8:10 PM telling (2001) ET (8) WONDER CHOUX (13) (12) CITYNEWS (6)(10)(21)(53) (22) CONSUMER (49) (32) PETS AND PEO- GLOBAL SHOW JEOP- (35) RENOVATE MY THE SUITE LIFE 12:00 AM (13) YOUNG & REST- NATIONAL (51) FAMILY GUY Part (13) THE OFFICE ARDY MARKETING PLE (16) WARDROBE 8:30 PM (5)(3) PROF. -

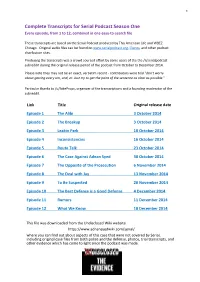

Serial Podcast Season One Every Episode, from 1 to 12, Combined in One Easy-To-Search File

1 Complete Transcripts for Serial Podcast Season One Every episode, from 1 to 12, combined in one easy-to-search file These transcripts are based on the Serial Podcast produced by This American Life and WBEZ Chicago. Original audio files can be found on www.serialpodcast.org, iTunes, and other podcast distribution sites. Producing the transcripts was a crowd sourced effort by some users of the the /r/serialpodcast subreddit during the original release period of the podcast from October to December 2014. Please note they may not be an exact, verbatim record - contributors were told "don't worry about getting every um, and, er. Just try to get the point of the sentence as clear as possible." Particular thanks to /u/JakeProps, organizer of the transcriptions and a founding moderator of the subreddit. Link Title Original release date Episode 1 The Alibi 3 October 2014 Episode 2 The Breakup 3 October 2014 Episode 3 Leakin Park 10 October 2014 Episode 4 Inconsistencies 16 October 2014 Episode 5 Route Talk 23 October 2014 Episode 6 The Case Against Adnan Syed 30 October 2014 Episode 7 The Opposite of the Prosecution 6 November 2014 Episode 8 The Deal with Jay 13 November 2014 Episode 9 To Be Suspected 20 November 2014 Episode 10 The Best Defense is a Good Defense 4 December 2014 Episode 11 Rumors 11 December 2014 Episode 12 What We Know 18 December 2014 This file was downloaded from the Undisclosed Wiki website https://www.adnansyedwiki.com/serial/ where you can find out about aspects of this case that were not covered by Serial, including original case files from both police and the defense, photos, trial transcripts, and other evidence which has come to light since the podcast was made.