Copyright by Lauren Elizabeth Wilks 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer

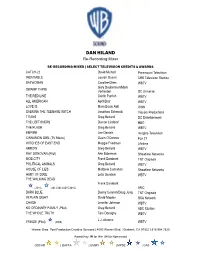

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer RE-RECORDING MIXER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS CATCH-22 David Michod Paramount Television INSATIABLE Lauren Gussis CBS Television Studios BATWOMAN Caroline Dries WBTV Gary Dauberman/Mark SWAMP THING Verheiden DC Universe THE RED LINE Cairlin Parrish WBTV ALL AMERICAN April Blair WBTV LOVE IS Mara Brock Akil OWN SABRINA THE TEENAGE WITCH Jonathan Schmock Viacom Productions TITANS Greg Berlanti DC Entertainment THE LEFTOVERS Damon Lindelof HBO THE FLASH Greg Berlanti WBTV EMPIRE Lee Daniels Imagine Television CINNAMON GIRL (TV Movie) Gavin O'Connor Fox 21 WITCHES OF EAST END Maggie Friedman Lifetime ARROW Greg Berlanti WBTV RAY DONOVAN (Pilot) Ann Biderman Showtime Networks MOB CITY Frank Darabont TNT Originals POLITICAL ANIMALS Greg Berlanti WBTV HOUSE OF LIES Matthew Carnahan Showtime Networks HART OF DIXIE Leila Gerstein WBTV THE WALKING DEAD Frank Darabont (2010) (2012/2014/2015/2016) AMC DARK BLUE Danny Cannon/Doug Jung TNT Originals IN PLAIN SIGHT David Maples USA Network CHASE Jennifer Johnson WBTV NO ORDINARY FAMILY (Pilot) Greg Berlanti ABC Studios THE WHOLE TRUTH Tom Donaghy WBTV J.J. Abrams FRINGE (Pilot) (2009) WBTV Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.7825 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS LIMELIGHT (Pilot) David Semel, WBTV HUMAN TARGET Jonathan E. Steinberg WBTV EASTWICK Maggie Friedman WBTV V (Pilot) Kenneth Johnson WBTV TERMINATOR: THE SARAH CONNER Josh Friedman CHRONICLES WBTV CAPTAIN -

Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006 Florida International University Division of University Relations

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Magazine Special Collections and University Archives Fall 2006 Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006 Florida International University Division of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/fiu_magazine Recommended Citation Florida International University Division of University Relations, "Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006" (2006). FIU Magazine. 4. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/fiu_magazine/4 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and University Archives at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Magazine by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE FALL 2006 20/20 VISION President Modesto A. Maidique crowns his 20-year anniversary at FIU with an historic accomplishment, winning approval for a new College of Medicine. Also in this issue: Alumna Dawn Ostroff ’80 FIU honors alumni College of Business takes the helm of a at largest-ever Administration expansion new television network Torch Awards Gala garners support THE 2006 GOLDEN PANTHERS FOOTBALL SEASON WILL BE THE HOTTEST ON RECORD WITH THE HISTORIC FIRST MATCHUP AGAINST THE UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI AT THE ORANGE BOWL. DON'T MISS A MOMENT, CALL FOR YOUR TICKETS TODAY: 1 -866-FIU-GAME FIU Golden Panthers 2006 Season Aug Middle Tennessee A 7 p.m. September 9* South Florida A 7 p.m. Raymond James Stadium, Tampa September 16* Bowling green H 6 p.m. Sept * Maryland Arkansas State Parents weekend North Texas University of Miami A TBA Orange Bowl, Miami October .21 Alabama A TBA INfoverrtber Louisiana-Monroe H 7 p.m. -

Gossip Girl-Season1 Episode3 (The Letter)

www.SSEcoach.com Gossip Girl-Season1 Episode3 – Blair reads her letter to Serena Title: Gossip Girl – The letter Time – 2:31 Part 1 - Script 1. Blair: Whenever something’s bothering you, I can always find you here. 2. Serena: You here for another catfight? 3. Serena: What’s that? 4. Blair: A letter; I wrote it to you when you were away at boarding school. 5. Blair: I never sent it. 6. Blair: Dear Serena, my world is falling apart and you’re the only one who would understand. My father left my mother for a 31 year old model; a male model. I feel like screaming because I don’t have anyone to talk to. 7. Blair: You’re gone. My dad’s gone. Nate’s acting weird. Where are you? Why don’t you call? Why did you leave without saying goodbye? 8. Blair: You’re supposed to be my best friend. I miss you so much. Love Blair. 9. Serena: Why didn’t you send it? I would’ve- 10. Blair: You would’ve what! 11. Blair: You knew Serena and you didn’t even call. 12. Serena: I didn’t know what to say to you. I didn’t know how to be your friend after what I did. I’m so sorry. 13. Blair: Erik told me what happened; I guess your family’s been going through a hard time too. 14. Gossip Girl: Spotted in Central Park: Two white flags waving. Could an Upper East Side peace accord be far off? 15. Gossip Girl: So what will it be? Truce or consequences? We all know one nation can’t have two queens. -

The Intertwining of Multimedia in Emma, Clueless, and Gossip Girl Nichole Decker Honors Scholar Project May 6, 2019

Masthead Logo Scholar Works Honors Theses Honors 2019 Bricolage on the Upper East Side: The nI tertwining of Multimedia in Emma, Clueless, and Gossip Girl Nichole Decker University of Maine at Farmington Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umf.maine.edu/honors_theses Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Decker, Nichole, "Bricolage on the Upper East Side: The nI tertwining of Multimedia in Emma, Clueless, and Gossip Girl" (2019). Honors Theses. 5. https://scholarworks.umf.maine.edu/honors_theses/5 This Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors at Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 Bricolage on the Upper East Side: The Intertwining of Multimedia in Emma, Clueless, and Gossip Girl Nichole Decker Honors Scholar Project May 6, 2019 “Okay, so you’re probably going, is this like a Noxzema commercial or what?” - Cher In this paper I will analyze the classic novel Emma, and the 1995 film Clueless, as an adaptive pair, but I will also be analyzing the TV series, Gossip Girl, as a derivative text. I bring this series into the discussion because of the ways in which it echos, parallels, and alludes to both Emma and Clueless individually, and the two as a source pair. I do not argue that the series is an actual adaptation, but rather, a sort of collage, recombining motifs from both source texts to create something new, exciting, and completely absurd. -

Faculty of Business Administration American Journal of Public Health

Faculty of Business Administration BRAGE Hedmark University of Applied Sciences Open Research Archive http://brage.bibsys.no/hhe/ This is the author’s version of the article published in American Journal of Public Health The article has been peer-reviewed, but does not include the publisher’s layout, page numbers and proof-corrections Citation for the published paper: Wang, H. & Singhal, A. (2016). East Los High: Transmedia Edutainment to Promote Sexual and Reproductive Health of Young Latina/o Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 106, 1002-1010. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303072 This article has open access full-text online: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303072 1 East Los High: Transmedia Edutainment to Promote Sexual and Reproductive Health of Young Latina/o Americans Hua Wang University at Buffalo, The State University of New York [email protected] Arvind Singhal The University of Texas at El Paso [email protected] Pre-Print Version 8BOH ) 4JOHIBM " 2016 &BTU-PT)JHI 5SBOTNFEJBFEVUBUJONFOUUP QSPNPUFTFYVBMBOESFQSPEVDUJWFIFBMUIPGZPVOH-BUJOBP"NFSJDBOT "NFSJDBO+PVSOBMPG1VCMJD)FBMUI, 106, 1002–1010. doi:10.2105/ AJPH.2016. 303072 2 Abstract Latina/o Americans are at high risk for sexually transmitted infections and teen pregnancies. Needed urgently are innovative health promotion approaches that are engaging and culturally sensitive. East Los High, a transmedia edutainment program, was purposefully designed to embed educational messages in entertainment narratives across several digital platforms to promote sexual and reproductive health among young Latina/o Americans. By employing analytics tracking, a viewer survey, and a lab experiment, we found that East Los High had a wide audience reach, strong audience engagement and, in general, a positive cognitive, emotional, and social impact on sexual and reproductive health communication and education. -

The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 2010 "Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Burnett, Tamy, ""Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 by Tamy Burnett A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Specialization: Women‟s and Gender Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Kwakiutl L. Dreher Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Kwakiutl L. Dreher Found in the most recent group of cult heroines on television, community- centered cult heroines share two key characteristics. The first is their youth and the related coming-of-age narratives that result. -

Byron Michael Purcell and Rodney S. Diggs Intend to Continue the Legacy of the Firm in Representing the Community and Bringing Justice

Allen Crabbe Hosts Free Bas- ketball Camp at Price High School Brianna Davison Gives Back to (See page B-1) Kids with Cancer (See page D-1) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBER 12 - 18, 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO. 33, $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years Years, The Voice The Voiceof Our of CommunityOur Community Speaking Speaking for forItself Itself.” THURSDAY, AUGUST 15, 2019 Byron Michael Purcell and Rodney S. Diggs intend to continue the legacy of the firm in representing the community and bringing justice. BY BRIAN W. CARTER Contributing Writer Welcome Ivie, Mc- Neill, Wyatt, Purcell & Diggs—the prestigious and Black-owned law firm in Los Angeles has added two exemplary lawyers to its title. IMW partners, Byron Michael Purcell and Rodney S. Diggs both come with a wealth of le- gal experience between the two of them and prov- en records at the firm. Se- nior partners, Rickey Ivie and Keith Wyatt shared a statement about adding their names to the firm. “Byron and Rodney have been major contribu- (From left) IMW attorneys Byron Michael Purcell and tors to the success and Rodney S Diggs. COURTESY growth of our firm for a (From left) Motown legends Smokey Robinson and Berry Gordy PHOTO E. MESIYAH MCGINNIS / SENTINEL long time. The change of dous attorneys, and we are is committed to service, the firm name is in recog- proud and blessed to work I love the commitment to BY IMANI SUMBI Harmony Gold Theater in ford, and of course, mem- nition of their past, pres- with them.”- Rickey Ivie & service—not only to its cli- Contributing Writer Los Angeles. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Thrill of the Chace

REVIEW Ed and Thrill of Jessica are dating in real life KELLY RUTHERFORD CE (Lily van der Woodsen) It’s a case of life imitating THELUCKY SHANNON O’M EARACHA KEEPS A DATE Ed and art as 40-year-old WITH GOSSIP GIRL NICE GUY NATE Chace are Kelly, who plays a great mates multi-divorced mum, off-screen battles for custody of her WAKE-UP call at 6am is not real-life son, Hermès. much fun, although if Chace ED WESTWICK Crawford – Gossip Girl’s Nate (Chuck A Bass), CHACE CRAWFORD Archibald – is at the end of the line, (Nate Archibald) and JESSICA could there be a better reason to get SZOHR (Vanessa Abrams) up in the morning? Nate and Vanessa briefly dated on So Grazia happily (and breathlessly) the show, but party-boy Ed is now takes the call from the Texan romancing Jessica in the real world – heart-throb, who has a rare day off despite the gay rumours that plague former flatmates Ed and Chace. from !lming the hit drama series. The 23-year-old is eager to tell us about his crush on Australia and his penchant for Aussie stars. “I want to get to Australia so bad,” Chace says. “Ed [Westwick, aka Chuck Bass] has of the been down there and he had a blast. Real-life drama s Australia is de!nitely next on my list. The accent, the girls!” CAST Despite having hordes of female GOSSIP GI RL fans, the actor remains surprisingly THE ON-SCREEN SOAP OPERA HAS grounded, mostly thanks to some NOTHING ON THEIR OFF-SCREEN PLOTS good ole southern values. -

GOSSIP GIRL by Cecily Von Ziegesar

Executive Producer Josh Schwartz Executive Producer Stephanie Savage Executive Producer Bob Levy Executive Producer Les Morgenstein Executive Producer John Stephens Co-Executive Producer Joshua Safran Producer Amy Kaufman Producer Joe Lazarov Episode 206 “New Haven Can Wait” Written by Alexandra McNally & Joshua Safran Directed by Norman Buckley Based on GOSSIP GIRL by Cecily von Ziegesar Double White Revisions 8/20/08, pg. 41 Goldenrod Revisions 8/14/08, pgs. 2, 3, 3A Green Revisions 8/12/08, pg. 16 Yellow Revisions 8/12/08, pgs. 5, 20, 20A-21, 22, 23, 31, 31A, 31B-32, 32A, 33, 36, 37, 38, 38A-39, 49A, 50, 51 Full Pink Revisions 8/11/08 Full Blue Revisions 8/8/08 Production #: 3T7606 Production Draft 8/5/08 © 2008 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. This script is the property of Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc. No portion of this script may be performed, reproduced or used by any means, or disclosed to, quoted or published in any medium without the prior written consent of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. “New Haven Can Wait” Character List CAST Serena van der Woodsen Blair Waldorf Dan Humphrey Jenny Humphrey Nate Archibald Chuck Bass Rufus Humphrey Lily Bass Eleanor Waldorf Dorota Vanessa Abrams Headmaster Prescott Headmistress Queller Assistant GUEST CAST * Dean Berube (pronounced Barraby) Jordan Steele Skull and Bones Leader Skull Bones Shirley History Professor Girl (Miss Steinberg) Yale Guy EXTRAS Constance and St. Jude’s Seniors Yale Students Serena’s Driver Yale Guys and Two Super-Hot Yale Girls Skull and Bones Members Three Masked -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. BA Bryan Adams=Canadian rock singer- Brenda Asnicar=actress, singer, model=423,028=7 songwriter=153,646=15 Bea Arthur=actress, singer, comedian=21,158=184 Ben Adams=English singer, songwriter and record Brett Anderson=English, Singer=12,648=252 producer=16,628=165 Beverly Aadland=Actress=26,900=156 Burgess Abernethy=Australian, Actor=14,765=183 Beverly Adams=Actress, author=10,564=288 Ben Affleck=American Actor=166,331=13 Brooke Adams=Actress=48,747=96 Bill Anderson=Scottish sportsman=23,681=118 Birce Akalay=Turkish, Actress=11,088=273 Brian Austin+Green=Actor=92,942=27 Bea Alonzo=Filipino, Actress=40,943=114 COMPLETEandLEFT Barbara Alyn+Woods=American actress=9,984=297 BA,Beatrice Arthur Barbara Anderson=American, Actress=12,184=256 BA,Ben Affleck Brittany Andrews=American pornographic BA,Benedict Arnold actress=19,914=190 BA,Benny Andersson Black Angelica=Romanian, Pornstar=26,304=161 BA,Bibi Andersson Bia Anthony=Brazilian=29,126=150 BA,Billie Joe Armstrong Bess Armstrong=American, Actress=10,818=284 BA,Brooks Atkinson Breanne Ashley=American, Model=10,862=282 BA,Bryan Adams Brittany Ashton+Holmes=American actress=71,996=63 BA,Bud Abbott ………. BA,Buzz Aldrin Boyce Avenue Blaqk Audio Brother Ali Bud ,Abbott ,Actor ,Half of Abbott and Costello Bob ,Abernethy ,Journalist ,Former NBC News correspondent Bella ,Abzug ,Politician ,Feminist and former Congresswoman Bruce ,Ackerman ,Scholar ,We the People Babe ,Adams ,Baseball ,Pitcher, Pittsburgh Pirates Brock ,Adams ,Politician ,US Senator from Washington, 1987-93 Brooke ,Adams -

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

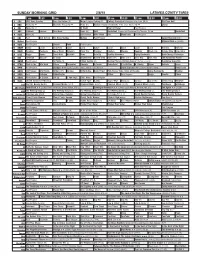

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B.