The Interview: Adam Lowe of Factum Arte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The British Museum Annual Reports and Accounts 2019

The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 HC 432 The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed on 19 November 2020 HC 432 The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 © The British Museum copyright 2020 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as British Museum copyright and the document title specifed. Where third party material has been identifed, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/ofcial-documents. ISBN 978-1-5286-2095-6 CCS0320321972 11/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fbre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Ofce The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 Contents Trustees’ and Accounting Ofcer’s Annual Report 3 Chairman’s Foreword 3 Structure, governance and management 4 Constitution and operating environment 4 Subsidiaries 4 Friends’ organisations 4 Strategic direction and performance against objectives 4 Collections and research 4 Audiences and Engagement 5 Investing -

018-245 ING Primavera CORR 24,5 X 29.Qxp

Under the High Patronage of the President of the Italian Republic !e Springtime of the Renaissance. Sculpture and the Arts in Florence – Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, March– August Paris, Musée du Louvre, September – January With the patronage of Concept by Website Ministero degli Affari Esteri Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi Netribe Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali Marc Bormand Ambassade de France en Italie Programming for families, youth and adults Curated by Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi Promoted and organized by Marc Bormand School groups and activities Sigma CSC With the collaboration of Ilaria Ciseri Exhibition reservation office Sigma CSC Realized by Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi Exhibition and ticket office staff TML Service Scholarly and editorial coordination and accompanying texts in the exhibition Multichannel ticket office Ludovica Sebregondi TicketOne Installation design Audioguide Luigi Cupellini START with the collaboration of Carlo Pellegrini Insurance Exhibition installation AON Artscope Galli Allestimenti Lloyd’s Atlas e Livelux Light Designers CS Insurance Service Stampa in Stampa Alessandro Terzo Transportation Franco Bianchi Arterìa Installation and condition report works on paper with Julie Guilmette Head of security Ulderigo Frusi Exhibition graphics and communication design RovaiWeber design Head of prevention and protection service Translation of accompanying texts in the exhibition Andrea Bonciani Stephen Tobin (Italian–English) Lara Fantoni (English–Italian) Electrical system assistance Xue Cheng (Italian–Chinese) and maintenance Mila Alieva (English–Russian) Bagnoli srl Gabrielle Giraudeau (Italian–French) Alarm system assistance Family itinerary and maintenance James M. Bradburne Professional Security srl Cristina Bucci Chiara Lachi Air-conditioning/heating system assistance and and maintenance Communication and promotion R.S. -

Dresden – Where Opera Never Ends Let’S Go to the Museum

marketing.dresden.de Dresden Info Service Spring 2013 Dresden – Where Opera never ends Let’s go to the museum Dear friend of Dresden, Dresden sets new tourism record: in 2012, for the first time Dresden. Let’s go to the museum. 2 ever, overnight stays in Dresden broke the 4 million barrier. The Dresden State Art Collections – One reason for this is the top spot achieved by the city’s a world-class museum association. 3 hotels in the recent Trivago.com Reputation Ranking global survey: Dresden’s hotels have the most satisfied customers Richard Wagner’s 200th birthday in the world! And large numbers of these visitors discovered celebrated in museums . .4 for themselves the immeasurable riches in the city‘s 50 and Magnificent and brilliant. The SKD celebrate more museums. The State Art Collections alone welcomed two major openings in 2013 . 6 more than 2.5 million visitors in 2012. More than enough reason then for us to set out on the trail of Dresden’s leg- Oldest, youngest, largest, smallest – endary museums, where the passion for collecting and Dresden’s superlative museums . 7 displaying things of beauty is strikingly obvious, as are Don’t miss these! Exhibition highlights in 2013. .9 their ambitious, ground-breaking contemporary exhibition projects. The Dresden City Museum, the Book Museum Please touch the exhibits! in the Saxon State and University Library (SLUB), and the Interactive museum experience . 11 Wagner-Stätten-Graupa complete the harmonious circle of Dresden’s vibrant tradition. The 200th anniversary of Richard Wagner’s birth will be celebrated here, as it will be in the Semper Opera House, the Frauenkirche and concert Legal notice . -

UK Rejection of Restitution of Artefacts: Confirmation Or Surprise?

25.05.2019 FEATURE ARTICLE UK Rejection Of Restitution Of Artefacts: Confirmation Or Surprise? By Kwame Opoku, Dr. ‘’Truth must be repeated constantly, because error is being repeatedly preached round about all the few, but by the masses. In the periodicals and encyclopaedias, in schools and universities, everywhe confident and comfortable in the feeling that it has the majority on its side.” Johann Wolfgang von G The United Kingdom Secretary for Culture is reported as having declared: “ Never mind the argume thing, let’s argue about how it gets to be seen ”. (2) Mr. Jeremy Wright whose pronouncements on o caused surprise made this statement in response to The Times with respect to the debate on restitutio The Minister argued that if artefacts were returned to their countries of origin, there would be no on see multiple objects:‘ if you followed the logic of restitution to its logical conclusion ,according to W ‘no single points where people can see multiple things’ Wright also stated that the United Kingdom Crown of Tewodros II, looted laws to enable restitution of cultural artefacts to the various countries. at Maqdala, Ethiopia in 1868, now in Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom. ‘His argument seemed to rely on the tired misconception that there would be nothing much left in our museums and “no single points wher things” if restitution was allowed. This kind of thinking flies in the face of the informed conversation about decolonisation, restitution and repatriation that is taking place in at government level in many countries in Europe. ‘(3) What Jeremy Wright is attempting to do is to revive the long discredited universal museum argument that artefacts of different cultures are understood when they are all gathered at one museum such as the British Museum. -

Museum Activism

MUSEUM ACTIVISM Only a decade ago, the notion that museums, galleries and heritage organisations might engage in activist practice, with explicit intent to act upon inequalities, injustices and environmental crises, was met with scepticism and often derision. Seeking to purposefully bring about social change was viewed by many within and beyond the museum community as inappropriately political and antithetical to fundamental professional values. Today, although the idea remains controversial, the way we think about the roles and responsibilities of museums as knowledge- based, social institutions is changing. Museum Activism examines the increasing significance of this activist trend in thinking and practice. At this crucial time in the evolution of museum thinking and practice, this ground-breaking volume brings together more than fifty contributors working across six continents to explore, analyse and critically reflect upon the museum’s relationship to activism. Including contribu- tions from practitioners, artists, activists and researchers, this wide-ranging examination of new and divergent expressions of the inherent power of museums as forces for good, and as activists in civil society, aims to encourage further experimentation and enrich the debate in this nascent and uncertain field of museum practice. Museum Activism elucidates the largely untapped potential for museums as key intellectual and civic resources to address inequalities, injustice and environmental challenges. This makes the book essential reading for scholars and students of museum and heritage studies, gallery studies, arts and heritage management, and politics. It will be a source of inspiration to museum practitioners and museum leaders around the globe. Robert R. Janes is a Visiting Fellow at the School of Museum Studies , University of Leicester, UK, Editor-in-Chief Emeritus of Museum Management and Curatorship, and the founder of the Coalition of Museums for Climate Justice. -

An Interview with Roderick Whitfield on the Stein Collection in the British Museum

An Interview with Roderick Whitfield on the Stein Collection in the British Museum Sonya S. Lee University of Southern California he Stein Collection in the British Museum is More than a century has passed since Stein first home to some of the most important artifacts brought manuscripts and objects from the ancient dTiscovered in China’s Central Asian regions. There Silk Road to England. 3 As expected, the first gener - are 249 paintings from Dunhuang and several ation of scholars who worked on these materials— thousand works from various sites along the an - most of whom were personally invited by Stein to cient Silk Road, including painted wooden panels, participate—focused on identifying the contents architectural ornaments, terracotta sculptures, and interpreting their significance within their coins, and textiles. All these works, along with over proper historical contexts, while Stein devoted 45,000 manuscripts and printed documents now himself to producing an impressive number of de - in the British Library as well as 221 paintings from tailed expedition reports and catalogues. The ex - Dunhuang and large murals and archaeological plorer’s own legacy did not become a subject of finds from Central Asian sites in the National Mu - inquiry until recent decades, when curators at the seum of New Delhi, were obtained by Sir Aurel British Library and the British Museum began to Stein (1862–1943) during three expeditions to the publish critical studies on Stein and his time. 4 As region that he undertook under the joint auspices our understanding of the history of archaeological of the Government of India and the Trustees of the exploration along the ancient Silk Road continues British Museum in the first two decades of the to evolve, the interest in reassessing Stein will no twentieth century. -

On Kawara 29,771 Days

This document was updated February 26, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. On Kawara 29,771 days SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 On Kawara and the Grande Complication, Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden 2019 On Kawara, David Lamelas, Jan Mot Gallery, Brussels [two-person exhibition] 2018 On Kawara, Krakow Witkin Gallery, Boston On Kawara: One Million Years (Reading), Museum MACAN, Jakarta, Indonesia 2017 On Kawara: One Million Years, Oratorio di San Ludovico Dorsoduro, Venice [organized by Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, England as part of 57th Venice Biennale] 2015 On Kawara: 1966, Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle, Belgium [catalogue] On Kawara: One Million Years, Asia House, London On Kawara—Silence, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York [catalogue] 2013 On Kawara: One Million Years, BOZAR - Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels 2012 On Kawara: Date Painting(s) in New York and 136 Other Cities, David Zwirner, New York [catalogue] On Kawara - Lived Time, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam On Kawara: One Million Years, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, England On Kawara: One Million Years, Jardin des Plantes, Paris 2010 On Kawara: Pure Consciousness at 19 Kindergartens, Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisco Art Institute 2009 On Kawara: One Million Years, David Zwirner, New York 2008 On Kawara: 10 Tableaux and 16,952 Pages, Dallas Museum of Art [catalogue] 2007 On Kawara, Michèle Didier at Christophe Daviet-Théry, Paris 2006 Eternal -

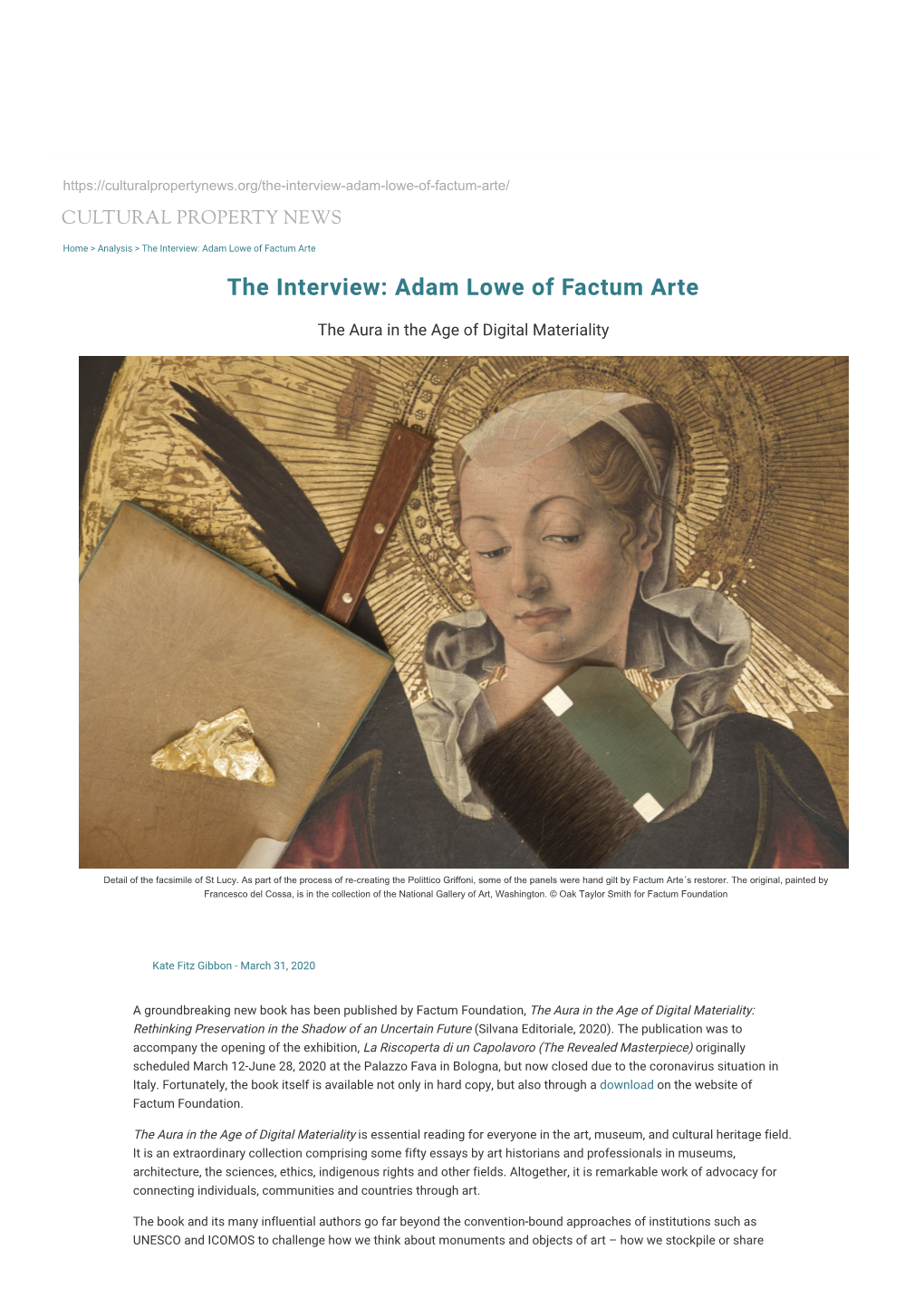

The Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality

THE AURA IN THE AGE OF DIGITAL MATERIALITY RETHINKING PRESERVATION IN THE SHADOW OF AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE The project is part of the exhibition LA RISCOPERTA DI UN CAPOLAVORO 12 March – 28 June 2020 Palazzo Fava, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Bologna A project of: Under the patronage of: A collection of essays assembled by Factum Foundation All projects carried out by the Factum Foundation are collaborative to accompany the exhibition and there are many people to thank. This is not the place to name everyone but some people have done a great deal to make all this The Materiality of the Aura: work possible including: Charlotte Skene Catling, Otto Lowe, New Technologies for Preservation Tarek Waly, Simon Schaffer, Pasquale Gagliardi, Fondazione Giorgio Cini and everyone in ARCHiVe, Bruno Latour, Hartwig Fischer, Palazzo Fava, Bologna Jerry Brotton, Roberto Terra, Cat Warsi, John Tchalenko, Manuela 12 March – 28 June 2020 Mena, Peter Glidewell, The Griffi th Institute, Emma Duncan, Lord Pontificio Consiglio della Cultura Rothschild, Fabia Bromofsky, Ana Botín, Paloma Botín, Lady Helen Hamlyn, Ziyavudin and Olga Magomedov, Rachid Koraïchi, Andrew ‘Factum Arte’ can be translated from the Latin as ‘made with Edmunds, Colin Franklin, Ed Maggs, the Hereford Mappa Mundi skill’. Factum’s practice lies in mediating and transforming material. Trust, Rosemary Firman, Philip Hewat-Jaboor, Helen Dorey, Peter In collaboration with: Its approach has emerged from an ability to record and respond to Glidewell, Purdy Rubin, Fernando Caruncho, Susanne Bickel, the subtle visual information manifest in the physical world around Markus Leitner and everyone at the Swiss Embassy in Cairo, Jim us. -

The British Museum Review 2019–20

Reaching out Review 2019/20 Contents 08 Director’s preface 10 Chairman’s foreword 14 Headlines Reaching out 26 New museums in Africa 28 Listening and learning 30 Fighting heritage crime 32 National moves 34 100 years of conservation and science National 38 National tours and loans 44 National partnerships 48 Archaeology and research in the UK International 56 International tours and loans 60 International partnerships Ready for X-ray 64 World archaeology and research 2020 marks 100 years since the BM launched one of the world’s London first dedicated museum science 72 Collection laboratories. Here the celebrated 76 Exhibitions Roman sculpture of the Discobolus 90 Learning (‘Discus-Thrower’) is shown in the X-ray imaging lab of the BM’s World 98 Support Conservation and Exhibitions Centre. 108 Appendices 6 Egyptian cat, c.600 BC Director’s preface The Gayer-Anderson cat, one of the most beloved objects in the BM, bears symbols of protection, healing and rebirth. (Height 14 cm) The month of March 2020 saw unprecedented Despite the profound change in our living and This situation does present an opportunity to think scenes at the British Museum as we responded working habits, and this strange enforced period more calmly, perhaps more profoundly, about our to the COVID 19 health crisis. BM colleagues of ‘exile’, I have been so pleased to see how our work and our achievements but also to think about were outstanding, helping us to close the audiences have continued to engage with the how to improve what we are doing once we have Museum in an orderly way and making sure collection and the BM digitally. -

SKD Annual Report 2015

www.skd.museum STAATLICHE KUNSTSAMMLUNGEN DRESDEN · ANNUAL REPORT 2015 2015 Powered by IN THE TRADITION OF THE COLLECTION OF THE HOUSE OF WETTIN A.L. 2015 annual report 6 Foreword 12 Exhibitions 14 Dahl and Friedrich 18 Supermarket of the Dead 20 Parts of a Unity 23 Luther and the Princes 26 The new Münzkabinett 30 War & Peace 34 Rosa Barba 36 Special exhibitions in Dresden and Saxony Contents 41 Special exhibitions in Germany and abroad 42 Science and research 44 Masterpieces from the former Weigang collection 46 “Europe / World” research and exhibition programme 49 Stories in Miniatures 50 Digitalisation and cataloguing 52 Restoring the Damascus Room 54 The Cuccina cycle by Veronese 58 Dresden/Prague around 1600 59 Prince Elector Augustus of Saxony 60 News in brief 62 Research projects 64 Publications 66 A changing institution 68 Developments at the Staatliche Ethnographische Sammlungen Sachsen 72 Staff matters 76 The museum and the public 78 Media and communication 82 Striking stories and histories 84 Focus on inclusion 86 New tours on offer for individual travellers 88 News in brief 96 Visitor numbers 97 Economic indicators 98 Thanks 100 Santiago Sierra at the Kupferstich-Kabinett 101 Friends associations 102 Acquisitions and gifts 106 Supporters and sponsors 110 Institutions 112 Publication details Dresden Art Festival – an evening on Scarred Landscapes, or the Wasteland of War The terrifying experience of violence and war – the opposite of the ideal of tolerance, open-mindedness and an interest in art – has shaped the face of Dresden, and not only in the 20th century. The paintings collected by Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden include world-famous exhibits on this topic, which were also made audible in the form of a promenade concert with corresponding music. -

Bring the Oldest Greek Exiles Home

Bring the oldest Greek exiles home Now that Brexit has finally been accomplished — the United Kingdom formally left the European Union on January 31 — Britain and its former continental partners are gearing up to negotiate new terms for doing business with each other. At least one of those partners, Greece, isn’t only looking ahead, it is also looking back. More than two centuries have elapsed since a British diplomat —- Thomas Bruce, the seventh Earl of Elgin — vandalized the Parthenon, looted many of its sculptures, and shipped them off to England. Lord Elgin eventually sold the carvings to the British Museum, where they have long been prominently displayed. But Greeks have never ceased resenting the theft, and intend to use the impending trade talks as leverage to secure the marble treasures’ return. At Greece’s request, the latest draft of the negotiating mandate being circulated among European governments includes a clause that could turn up the heat on Britain to restore the Parthenon sculptures to their rightful home. The draft language calls for “the return or restitution of unlawfully removed cultural objects to their country of origin.” While it doesn’t mention the two-and-a-half thousand year old marbles specifically, it clearly sets the groundwork for renewing pressure on London to rectify, at long last, one of history’s most notorious cases of cultural theft. The British Museum has always denied that Elgin’s removal of the Parthenon marbles was unlawful. Hartwig Fischer, the museum’s director, said in a BBC radio interview that the sculptures were brought to Britain “with the explicit permission of the Ottoman empire, the government in place back then” and that it “was not a burglaries case.” So Elgin maintained at the time. -

The Performance of Art: Picasso, Léger, and Modern Dance, 1917

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Summer 8-1-2012 The eP rformance of Art: Picasso, Léger, and Modern Dance, 1917-1925 Amanda Holly Beresford Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Beresford, Amanda Holly, "The eP rformance of Art: Picasso, Léger, and Modern Dance, 1917-1925" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1027. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1027 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Art History and Archaeology The Performance of Art: Picasso, Léger, and Modern Dance 1917-1925 by Amanda Holly Beresford A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2012 Saint Louis, Missouri Copyright by Amanda Holly Beresford 2012 Acknowledgements My thanks are due to the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Washington University for the award of a Research Travel grant, which enabled me to travel to Paris and London in the summer of 2010 to undertake research into the