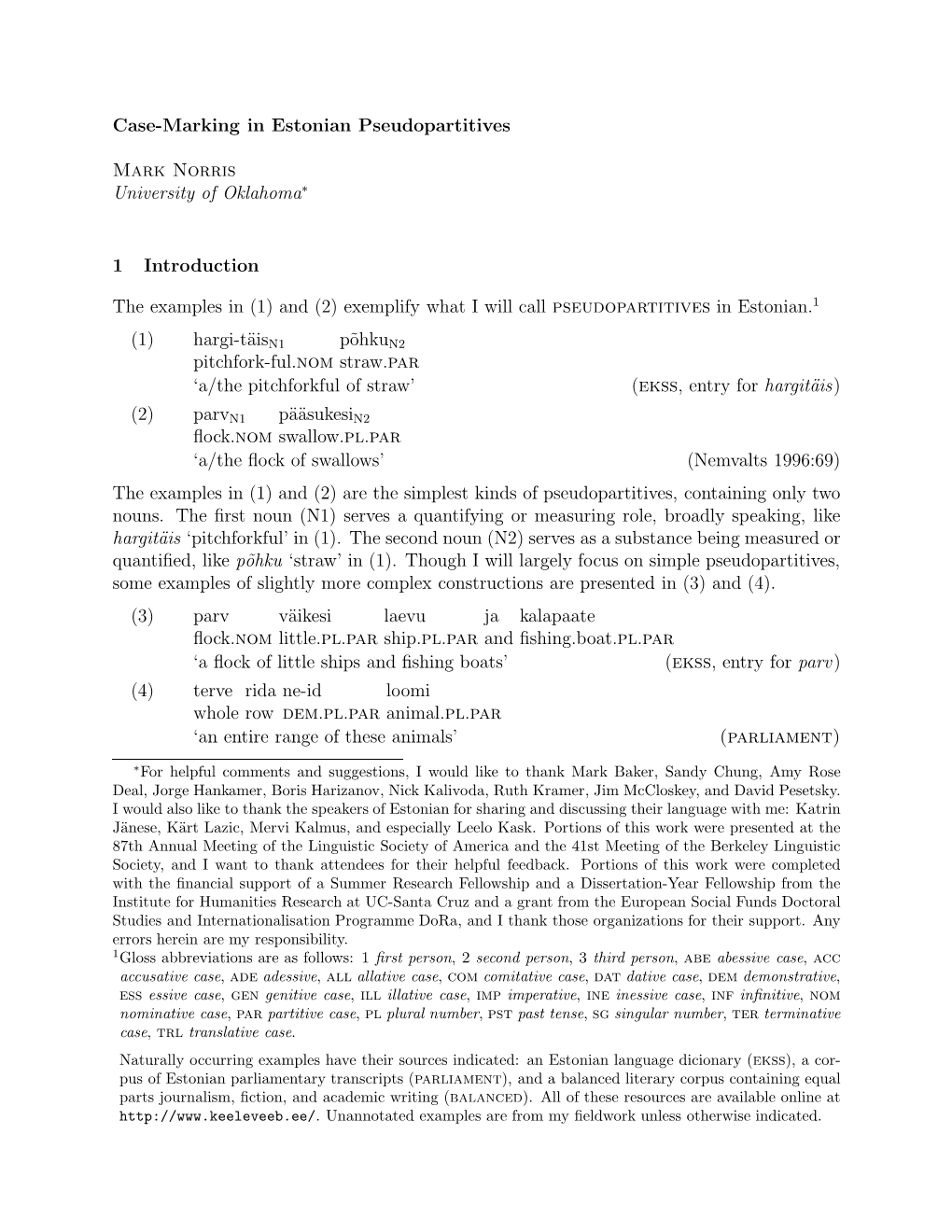

Case-Marking in Estonian Pseudopartitives Mark Norris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ongoing Eclipse of Possessive Suffixes in North Saami

Te ongoing eclipse of possessive sufxes in North Saami A case study in reduction of morphological complexity Laura A. Janda & Lene Antonsen UiT Te Arctic University of Norway North Saami is replacing the use of possessive sufxes on nouns with a morphologically simpler analytic construction. Our data (>2K examples culled from >.5M words) track this change through three generations, covering parameters of semantics, syntax and geography. Intense contact pressure on this minority language probably promotes morphological simplifcation, yielding an advantage for the innovative construction. Te innovative construction is additionally advantaged because it has a wider syntactic and semantic range and is indispensable, whereas its competitor can always be replaced. Te one environment where the possessive sufx is most strongly retained even in the youngest generation is in the Nominative singular case, and here we fnd evidence that the possessive sufx is being reinterpreted as a Vocative case marker. Keywords: North Saami; possessive sufx; morphological simplifcation; vocative; language contact; minority language 1. Te linguistic landscape of North Saami1 North Saami is a Uralic language spoken by approximately 20,000 people spread across a large area in northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland. North Saami is in a unique situation as the only minority language in Europe under intense pressure from majority languages from two diferent language families, namely Finnish (Uralic) in the east and Norwegian and Swedish (Indo-European 1. Tis research was supported in part by grant 22506 from the Norwegian Research Council. Te authors would also like to thank their employer, UiT Te Arctic University of Norway, for support of their research. -

Tánczos Orsolya Causative Constructions and Their

TÁNCZOS ORSOLYA CAUSATIVE CONSTRUCTIONS AND THEIR SYNTACTIC ANALYSIS IN THE UDMURT LANGUAGE (M ŰVELTET Ő SZERKEZETEK ÉS MONDATTANI ELEMZÉSÜK AZ UDMURT NYELVBEN) DOKTORI (PHD) ÉRTEKEZÉS Pázmány Péter Katolikus Egyetem Bölcsészet és Társadalomtudományi Kar Nyelvtudományi Doktori Iskola Vezet ője: Prof. É. Kiss Katalin egyetemi tanár, akadémikus FINNUGOR M ŰHELY TÉMAVEZET Ő: PROF. CSÚCS SÁNDOR EGYETEMI TANÁR BUDAPEST 2015 Nagyapámnak, aki Zeppelint látott 2 CONTENTS Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 7 Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................... 10 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 12 1.1 The aim of the dissertation .................................................................................. 12 1.2 The Udmurt data of the dissertation................................................................... 14 1.2.1 Acceptability judgments ............................................................................... 14 1.2.2 Data collecting method ................................................................................ 15 1.2.3 The examples ................................................................................................ 16 1.3 The Udmurt language .......................................................................................... 16 -

CASE MARKING of the PREDICATIVE in ESTONIAN* 1. Introduction the Encoding O

Linguistica Uralica XXXIX 2003 3 MATI ERELT (Tartu), HELLE METSLANG (Tallinn) CASE MARKING OF THE PREDICATIVE IN ESTONIAN* Abstract. In Estonian the prototypical non-verbal predicate is a noun or an adjective in the nominative case. The noun expresses class-inclusion, the adjective — a property. The prototypical predicative is non-marked in regard to time-stability. Time-stability can be marked by a non-prototypical form both in the case of class-inclusion as well as in the case of property. In the case of class-inclusion, temporary and random class-membership are marked by the translative, not by the essive. This feature makes Estonian similar to Russian and the Baltic languages and distinguishes it from Finnish. The essive is a relatively new case in Standard Estonian and its use is restricted. In copula sentences the essive can only be found as a marker of secondary predication. Temporariness of a property is marked by a non-prototypical clause pattern. The ways of marking the property depend on the semantic type of the prop- erty. 1. Introduction The encoding of adjectival and nominal predicates in the languages of the Circum-Baltic area has a peculiar feature, noticed recently once again by Leon Stassen (2001). Namely, in most languages of this area the nonverbal predicate can be encoded in two ways — in the nominative and in some oblique cases. In L. Stassen’s opinion, the nominative is used in situations that are relatively ’time-stable’ (in the sense of Givon 1984), whereas the encoding emphasizes the temporary nature of the situation. More con- cretely, for predicate adjectives, the nominative points to the ’permanent’ or ’inherent’ character of the property predicated by the adjective, for pred- icate nominals the use of the nominative indicates class-membership, which is, in some way, essential to the subject. -

Berkeley Linguistics Society

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FORTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING OF THE BERKELEY LINGUISTICS SOCIETY February 7-8, 2015 General Session Special Session Fieldwork Methodology Editors Anna E. Jurgensen Hannah Sande Spencer Lamoureux Kenny Baclawski Alison Zerbe Berkeley Linguistics Society Berkeley, CA, USA Berkeley Linguistics Society University of California, Berkeley Department of Linguistics 1203 Dwinelle Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-2650 USA All papers copyright c 2015 by the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN: 0363-2946 LCCN: 76-640143 Contents Acknowledgments . v Foreword . vii The No Blur Principle Effects as an Emergent Property of Language Systems Farrell Ackerman, Robert Malouf . 1 Intensification and sociolinguistic variation: a corpus study Andrea Beltrama . 15 Tagalog Sluicing Revisited Lena Borise . 31 Phonological Opacity in Pendau: a Local Constraint Conjunction Analysis Yan Chen . 49 Proximal Demonstratives in Predicate NPs Ryan B . Doran, Gregory Ward . 61 Syntax of generic null objects revisited Vera Dvořák . 71 Non-canonical Noun Incorporation in Bzhedug Adyghe Ksenia Ershova . 99 Perceptual distribution of merging phonemes Valerie Freeman . 121 Second Position and “Floating” Clitics in Wakhi Zuzanna Fuchs . 133 Some causative alternations in K’iche’, and a unified syntactic derivation John Gluckman . 155 The ‘Whole’ Story of Partitive Quantification Kristen A . Greer . 175 A Field Method to Describe Spontaneous Motion Events in Japanese Miyuki Ishibashi . 197 i On the Derivation of Relative Clauses in Teotitlán del Valle Zapotec Nick Kalivoda, Erik Zyman . 219 Gradability and Mimetic Verbs in Japanese: A Frame-Semantic Account Naoki Kiyama, Kimi Akita . 245 Exhaustivity, Predication and the Semantics of Movement Peter Klecha, Martina Martinović . 267 Reevaluating the Diphthong Mergers in Japono-Ryukyuan Tyler Lau . -

A Case Study in Language Change

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-17-2013 Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change Ian Hollenbaugh Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hollenbaugh, Ian, "Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change" (2013). Honors Theses. 2243. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2243 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Elementary Ghau Aethauic Grammar By Ian Hollenbaugh 1 i. Foreword This is an essential grammar for any serious student of Ghau Aethau. Mr. Hollenbaugh has done an excellent job in cataloguing and explaining the many grammatical features of one of the most complex language systems ever spoken. Now published for the first time with an introduction by my former colleague and premier Ghau Aethauic scholar, Philip Logos, who has worked closely with young Hollenbaugh as both mentor and editor, this is sure to be the definitive grammar for students and teachers alike in the field of New Classics for many years to come. John Townsend, Ph.D Professor Emeritus University of Nunavut 2 ii. Author’s Preface This grammar, though as yet incomplete, serves as my confession to what J.R.R. Tolkien once called “a secret vice.” History has proven Professor Tolkien right in thinking that this is not a bizarre or freak occurrence, undergone by only the very whimsical, but rather a common “hobby,” one which many partake in, and have partaken in since at least the time of Hildegard of Bingen in the twelfth century C.E. -

Adpositions and Case: Alternative Realisation and Concord*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Adpositions and Case: Alternative Realisation and Concord* Marcel den Dikken and Éva Dékány This paper presents an outlook on ‘inherent case’ that ties it consistently to the cat- egory P, in either of two ways: the inherent case particle is either an autonomous spell-out of P or, in Emonds’ (1985, 1987) term, an alternative realisation of a silent P (i.e., a case morpheme on P’s nominal complement that licenses the silence of P). The paper also unfolds a perspective on case concord that analyses it as the copying of morphological material rather than the matching of morphological features. These proposals are put to the test in a detailed analysis of the case facts of Estonian, with particular emphasis on the distinction, within its eleven ‘semantic’ cases, between the seven spatial cases (analysed as alternative realisations of a null P) and the last four cases (treated as autonomous realisations of postpositions). This analysis of the Estonian case system has repercussions for the status of genitive case (structural vs inherent), and for the analysis of (the distribution of ) case concord. It also prompts a novel, purely syntactic outlook on case distribution in pseudo-partitives, exploiting a key contrast between Agree and the Spec-Head relation: when agreement involves the Spec-Head relation, it is subject to a condition. Keywords: adposition, alternative realisation, case, concord, exponence, pseudo-partitive 1 Preliminaries 1.1 Semantic cases as autonomous or alternative realisations of P Semantic cases of case-rich languages, such as the inessive or the ablative, translate in case-poor languages such as English with the aid of a designated spatial adposition, such as locative in (for ) or directional om (for ). -

1 Tsezian Languages Bernard Comrie, Maria Polinsky, and Ramazan

Tsezian Languages Bernard Comrie, Maria Polinsky, and Ramazan Rajabov Max-Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany University of California, San Diego, USA Makhachkala, Russia 1. Sociolinguistic Situation1 The Tsezian (Tsezic, Didoic) languages form part of the Daghestanian branch of the Nakh-Daghestanian (East Caucasian) language family. They form one branch of an Avar-Andi-Tsez grouping within the family, the other branch of this grouping being Avar-Andi. Five Tsezian languages are conventionally recognized: Khwarshi (Avar x∑arßi, Khwarshi a¥’ilqo), Tsez (Avar, Tsez cez, also known by the Georgian name Dido), Hinuq (Avar, Hinuq hinuq), Bezhta (Avar beΩt’a, Bezhta beΩ¥’a. also known by the Georgian name Kapuch(i)), and Hunzib (Avar, Hunzib hunzib), although the Inkhokwari (Avar inxoq’∑ari, Khwarshi iqqo) dialect of Khwarshi and the Sagada (Avar sahada, Tsez so¥’o) dialect of Tsez are highly divergent. Tsez, Hinuq, Bezhta, and Hunzib are spoken primarily in the Tsunta district of western Daghestan, while Khwarshi is spoken primarily to the north in the adjacent Tsumada district, separated from the other Tsezian languages by high mountains. (See map 1.) In addition, speakers of Tsezian languages are also to be found as migrants to lowland Daghestan, occasionally in other parts of Russia and in Georgia. Estimates of the number of speakers are given by van den Berg (1995) as follows, for 1992: Tsez 14,000 (including 6,500 in the lowlands); Bezhta 7,000 (including 2,500 in the lowlands); Hunzib 2,000 (including 1,300 in the lowlands); Hinuq 500; Khwarshi 1,500 (including 600 in the lowlands). -

Estonian and Latvian Verb Government Comparison

TARTU UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF ESTONIAN AND GENERAL LINGUISTICS DEPARTMENT OF ESTONIAN AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE Miķelis Zeibārts ESTONIAN AND LATVIAN VERB GOVERNMENT COMPARISON Master thesis Supervisor Dr. phil Valts Ernštreits and co-supervisor Mg. phil Ilze Tālberga Tartu 2017 Table of contents Preface ............................................................................................................................... 5 1. Method of research .................................................................................................... 8 2. Description of research sources and theoretical literature ......................................... 9 2.1. Research sources ................................................................................................ 9 2.2. Theoretical literature ........................................................................................ 10 3. Theoretical research background ............................................................................. 12 3.1. Cases in Estonian and Latvian .......................................................................... 12 3.1.1. Estonian noun cases .................................................................................. 12 3.1.2. Latvian noun cases .................................................................................... 13 3.2. The differences and similarities between Estonian and Latvian cases ............. 14 3.2.1. The differences between Estonian and Latvian case systems ................... 14 3.2.2. The similarities -

Words and Paradigms in the Mental Lexicon by Kaidi L˜Oo a Thesis

Words and Paradigms in the Mental Lexicon by Kaidi Loo˜ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics University of Alberta Examining Committee: Juhani Jarvikivi,¨ Supervisor R. Harald Baayen, Supervisor Antti Arppe, Supervisory Committee Herbert Colston, Examiner James P. Blevins, Examiner c Kaidi Loo,˜ 2018 Abstract This dissertation examines the comprehension and production of Estonian case- inflected nouns. Estonian is a morphologically complex Finno-Ugric language with 14 cases in both singular and plural for each noun. Because storing millions of forms in memory seems implausible, languages like Estonian are often taken to be prime candidates for rule-driven morpheme-based processing. However, not all Estonian nouns actually occur in all their 28 cases, but only in cases that make sense based on the meaning of the word. For instance, for jalg ‘foot/leg’, the nom- inative plural jalad ‘feet/legs’ is very common, whereas the essive singular case jalana ‘as a foot/leg’ rarely ever gets used. Furthermore, Estonian inflected forms cluster into inflectional paradigms, which typically come with only a few inflected variants from which other forms in the paradigm can be predicted. Hence, the number of forms that a speaker would need to memorize is much smaller than the number of forms that one can understand or produce. Based on these observations, we aimed to clarify lexical-distributional prop- erties that co-determine Estonian processing. Using a large number of items and generalized mixed effects modeling, we tested the influence of a number of lexical measures, such as lemma frequency, whole-word frequency, morphological family size, inflectional entropy, orthographic length and orthographic neighbourhood density (all calculated on the basis of a 15-million token Estonian corpus). -

Janne Bondi Johannessen (Ed.)

Oslo Studies in Language 3 (2) / 2011 Janne Bondi Johannessen (ed.) Language Variation Infrastructure Papers on selected projects Oslo Studies in Language General editors: Atle Grønn and Dag Haug Editorial board International: Henning Andersen, Los Angeles (historical linguistics) Östen Dahl, Stockholm (typology) Laura Janda, Tromsø/UNC Chapel Hill (Slavic linguistics, cognitive linguistics) Terje Lohndal, Maryland (syntax and semantics) Torgrim Solstad, Stuttgart (German linguistics, semantics and pragmatics) Arnim von Stechow, Tübingen (semantics and syntax) National: Johanna Barðdal, Bergen (construction grammar) Øystein Vangsnes, Tromsø (Norwegian, dialect syntax) Local: Cecilia Alvstad, ILOS (Spanish, translatology) Hans Olav Enger, ILN (Norwegian, cognitive linguistics) Ruth E. Vatvedt Fjeld, ILN (Norwegian, lexicography) Jan Terje Faarlund, CSMN, ILN (Norwegian, syntax) Cathrine Fabricius-Hansen, ILOS (German, contrastive linguistics) Carsten Hansen, CSMN, IFIKK (philosophy of language) Christoph Harbsmeier, IKOS (Chinese, lexicography) Hilde Hasselgård, ILOS (English, corpus linguistics) Hans Petter Helland, ILOS (French, syntax) Janne Bondi Johannessen, ILN, Text Laboratory (Norwegian, language technology) Kristian Emil Kristoffersen, ILN (cognitive linguistics) Helge Lødrup, ILN (syntax) Gunvor Mejdell, IKOS (Arabic, sociolinguistics) Christine Meklenborg Salvesen, ILOS (French linguistics, historical linguistics) Diana Santos, ILOS (Portuguese linguistics, computational linguistics) Ljiljana Saric, ILOS (Slavic linguistics) Bente Ailin Svendsen, ILN (second language acquisition) Oslo Studies in Language 3 (2) / 2011 Janne Bondi Johannessen (ed.) Language Variation Infrastructure Papers on selected projects Oslo Studies in Language, 3(2), 2011. Janne Bondi Johannessen (ed.): Language Variation Infrastructure. Papers on selected projects. Oslo, University of Oslo ISSN 1890-9639 © 2011 the authors Set in LATEX fonts Gentium Book Basic and Linux Libertine by Rune Lain Knudsen, Vladyslav Dorokhin and Atle Grønn. Cover design by UniPub publishing house. -

Grammatical Case in Estonian

Grammatical Case in Estonian Merilin Miljan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences, University of Edinburgh September 2008 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is of my own composition, and that it contains no material previously submitted for the award of any other degree. The work reported in this thesis has been executed by myself, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Merilin Miljan ii Abstract The aim of this thesis is to show that standard approaches to grammatical case fail to provide an explanatory account of such cases in Estonian. In Estonian, grammatical cases form a complex system of semantic contrasts, with the case-marking on nouns alternating with each other in certain constructions, even though the apparent grammatical functions of the noun phrases themselves are not changed. This thesis demonstrates that such alternations, and the differences in interpretation which they induce, are context dependent. This means that the semantic contrasts which the alternating grammatical cases express are available in some linguistic contexts and not in others, being dependent, among other factors, on the semantics of the case- marked noun and the semantics of the verb it occurs with. Hence, traditional approaches which treat grammatical case as markers of syntactic dependencies and account for associated semantic interpretations by matching cases directly to semantics not only fall short in predicting the distribution of cases in Estonian but also result in over-analysis due to the static nature of the theories which the standard approach to case marking comprises. -

Partitive-Accusative Alternations in Balto-Finnic Languages

Proceedings of the 2003 Conference of the Australian Linguistic Society 1 Partitive-Accusative Alternations in Balto-Finnic Languages AET LEES [email protected]. au 1. Introduction The present study looks at the case of direct objects of transitive verbs in the Balto-Finnic languages Estonian and Finnish, comparing the two languages. There are three structural or grammatical cases in Estonian: nominative, genitive and partitive. Finnish, in addition to these three, has a separate accusative case form, but only in the personal pronoun paradigm. All of these cases are used for direct objects, but they all, except the Finnish personal pronoun accusative, also have other uses. 2. Selection of object case Only clauses with active verbs have been considered in the present study. In all negative clauses the direct object is in the partitive case. In affirmative clauses, if the action is completed and the object is total, that is, the entire object is involved in the action, the case used is the accusative. The term ‘accusative’ is used as a blanket term for the non-partitive object case. In Estonian, more commonly than in Finnish, the completion of the event is indicated by an adverbial phrase or an oblique, indicating a change in position or state of the object. The total object is usually definite, or at least specific. If the action is not completed, or if it involves only part of the object, the partitive case is used. A partial object must be divisible, i.e. a mass noun or a plural count noun, but if the aspect is irresultative, the partitive object may be a singular count noun.