Musical Instruments and Material Culture Professor Tim Ingold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Programme for the Xvith International Congress of Celtic Studies

Logo a chynllun y clawr Cynlluniwyd logo’r XVIeg Gyngres gan Tom Pollock, ac mae’n seiliedig ar Frigwrn Capel Garmon (tua 50CC-OC50) a ddarganfuwyd ym 1852 ger fferm Carreg Goedog, Capel Garmon, ger Llanrwst, Conwy. Ceir rhagor o wybodaeth ar wefan Sain Ffagan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru: https://amgueddfa.cymru/oes_haearn_athrawon/gwrthrychau/brigwrn_capel_garmon/?_ga=2.228244894.201309 1070.1562827471-35887991.1562827471 Cynlluniwyd y clawr gan Meilyr Lynch ar sail delweddau o Lawysgrif Bangor 1 (Archifau a Chasgliadau Arbennig Prifysgol Bangor) a luniwyd yn y cyfnod 1425−75. Mae’r testun yn nelwedd y clawr blaen yn cynnwys rhan agoriadol Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, cyfieithiad Cymraeg o De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum, gan Hu Sant (Hugo o St. Victor). Rhan o ramadeg barddol a geir ar y clawr ôl. Logo and cover design The XVIth Congress logo was designed by Tom Pollock and is based on the Capel Garmon Firedog (c. 50BC-AD50) which was discovered in 1852 near Carreg Goedog farm, Capel Garmon, near Llanrwst, Conwy. Further information will be found on the St Fagans National Museum of History wesite: https://museum.wales/iron_age_teachers/artefacts/capel_garmon_firedog/?_ga=2.228244894.2013091070.156282 7471-35887991.1562827471 The cover design, by Meilyr Lynch, is based on images from Bangor 1 Manuscript (Bangor University Archives and Special Collections) which was copied 1425−75. The text on the front cover is the opening part of Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, a Welsh translation of De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum (Hugo of St. Victor). The back-cover text comes from the Bangor 1 bardic grammar. -

Freeandfreak Ysince

FREEANDFREAKYSINCE | DECEMBER THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | DECEMBER | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE TR - YEARINREVIEW 20 TheInternetTheyearofTikTok theWorldoff erstidylessonson “bootgaze”crewtheKeenerFamily @ 04 TheReaderThestoryof 21 DanceInayearoflosswefound Americanpowerdynamicsand returnwithasecondEP astoldthroughsomeofourfavorite thatdanceiseverywhere WildMountainThymefeaturesone PPTB covers 22 TheaterChicagotheaterartists ofthemostagonizingcourtshipsin OPINION PECKH 06 FoodChicagorestaurantsate rosetochallengesandcreated moviehistory 40 NationalPoliticsWhen ECS K CLR H shitthisyearAlotofshitwasstill newonesin politiciansselloutwealllose GD AH prettygreat 24 MoviesRelivetheyearinfi lm MUSIC &NIGHTLIFE 42 SavageLoveDanSavage MEP M 08 Joravsky|PoliticsIthinkwe withthesedoublefeatures 34 ChicagoansofNoteDoug answersquestionsaboutmonsters TDEKR CEBW canallagreethenextyearhasgot 28 AlbumsThebestoverlooked Maloneownerandleadengineer inbedandmothersinlaw AEJL tobebetter Chicagorecordsof JamdekRecordingStudio SWMD LG 10 NewsOntheviolencesadness 30 GigPostersTheReadergot 35 RecordsofNoteApandemic DI BJ MS CLASSIFIEDS EAS N L andhopeof creativetofi ndwaystokeep can’tstopthemusicandthisweek 43 Jobs PM KW 14 Isaacs|CultureSheearned upli ingChicagoartistsin theReaderreviewscurrentreleases 43 Apartments&Spaces L CSC-J thetitlestillhewasdissingher! 32 MusiciansThemusicscene byDJEarltheMiyumiProject 43 Marketplace SJR F AM R WouldhedothesametosayDr doubleddownonmutualaidand FreddieOldSoulMarkLanegan CEBN B Kissinger? fundraisingforcommunitygroups -

Download Booklet

Heavenly Harp BEST LOVED classical harp music Heavenly Harp Best loved classical harp music 1 Alphonse HASSELMANS (1845–1912) 10 Henriette RENIÉ (1875–1956) La Source, Op. 44 3:55 Danse des Lutins 3:59 Erica Goodman (8.573947) Judy Loman (8.554347) 2 Hugo REINHOLD (1854–1935) 11 Marcel TOURNIER (1879–1951) Impromptu in C sharp minor, Op. 28, No. 3 5:35 Vers la source dans le bois 4:18 Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) (‘Towards the Fountain in the Wood’) Judy Loman (8.554561) 3 John THOMAS (1826–1913) Dyddiau Mebyd (‘Scenes of Childhood’) – 3:05 12 Gabriel FAURÉ (1845–1924) II. Toriad y Dydd (‘The Dawn of Day’) Une chatelaine en sa tour, Op. 110 4:41 Lipman Harp Duo (8.570372) Judy Loman (8.554561) 4 Gaetano DONIZETTI (1797–1848) 13 Elias PARISH ALVARS (1808–1849) Lucia di Lammermoor, Act 1 Scene 2 4:25 Serenade, Op. 83 – Serenade 7:13 (arr. A.H. Zabel) Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) 14 Gabriel PIERNÉ (1863–1937) 5 Marcel GRANDJANY (1891–1975) Impromptu-caprice, Op. 9 5:51 Fantasy on a Theme of Haydn, Op. 31 7:54 Ellen Bødtker (8.555328) Judy Loman (8.554561) 15 Nino ROTA (1911–1979) 6 Manuel de FALLA (1876–1946) Toccata 2:33 La vida breve, Act II – 4:11 Elisa Netzer (8.573835) Danse espagnole No. 1 (ver. For 2 guitars) Judy Loman (8.554561) 16 John PARRY (1710–1782) Sonata No. 2 – Siciliana 2:06 7 Sophia DUSSEK (1775–1847) Judy Loman (8.554347) Sonata – Allegro 2:39 Judy Loman (8.554347) 17 Carl Philipp Emanuel BACH (1714–1788) 12 Variations on La folia d’Espagne, 9:13 8 Louis SPOHR (1784–1859) Wq. -

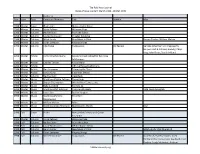

The Folk Harp Journal Index of Issue Content March 1986 - Winter 1998

The Folk Harp Journal Index of Issue Content March 1986 - Winter 1998 Author or Year Issue Type Composer/Arranger Title Subtitle Misc 1998 Winter Cover Illustration Make a Joyful Noise 1998 Winter Column Sylvia Fellows Welcome Page 1998 Winter Column Nadine Bunn From the Editor 1998 Winter Column Laurie Rasmussen Chapter Roundup 1998 Winter Column Mitch Landy New Music in Print Harper Tasche; William Mahan 1998 Winter Column Dinah LeHoven Ringing Strings 1998 Winter Column Alys Howe Harpsounds CD Review Verlene Schermer; Lori Pappajohn; Harpers Hall & Culinary Society; Chrys King; John Doan; David Helfand 1998 Winter Article Patty Anne McAdams Second annual retreat for Bay Area folk harpers 1998 Winter Article Charles Tanner A Cool Harp! 1998 Winter Article Fifth Gulf Coast Celtic harp 1998 Winter Article Ann Heymann Trimming the Tune 1998 Winter Article James Kurtz Electronic Effects 1998 Winter Column Nadine Bunn Classifieds 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Sylvia Fellows Three Kings 1998 Winter Music Sharon Thormahlen Where River Turns to sky 1998 Winter Music Reba Lunsford Tootie's Jig 1998 Winter Music Traditional/M. Schroyer The Friendly Beats 12th Century English 1998 Winter Music Joyce Rice By Yon Yangtze 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Serena He is Born Underwood 1998 Winter Music William Mahan Adios 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Ann Heymann MacDonald's March Irish 1998 Fall Cover Photo New Zealand's Harp and Guitar Ensemble 1998 Winter Column Sylvia Fellows Welcome Page 1998 Fall Column Nadine Bunn From the Editor 1998 Fall Column -

Harp Start Book 1 Handbook and Guide

Harp Start Book 1 Handbook and Guide 1 2 Harp Start Book 1 - Guidebook Introduction Welcome to the Handbook and Guide to Harp Start Book 1. This material is provided as extra information that you might have missed at your lesson, or you want to read in advance of learning the pieces in Harp Start. There are little versions of each page for reference, though if you have an earlier edition of Harp Start Book 1, you may detect some small differences as I continually try to improve the book. There are 3 appendices at the back: Appendix 1 is “How to Read Music Notation”, which may be profitably consulted by those with no musical literacy background. It is a harp-centered approach to the subject, and though it scratches the surface, it should get you through the beginning stages. Appendix 2 is “Sharps, Flats and Levers”. Appendix 3 is “Using the Harp Start Bonus Tuning Reference Chart” which will help you tune your harp and organize your levers. Some people use this book with a teaher, and others without. The italic notes are info for teachers with more detail about how I use the pages, but will be good advice for everyone. I use harp jewels in my teaching. They are little stick-on plastic jewels, sometimes known as diamonds ⋄ . I use them mostly just above the knuckle to be a tactile and very sparkly landing pad for the tip of the thumb. (I don’t wrap the thumb around the finger, but relax onto the pointy pillow on the side of, just above, the knuckle. -

Boris Absolutego Full Album Download Torrent Boris Absolutego Full Album Download Torrent

boris absolutego full album download torrent Boris absolutego full album download torrent. 'Absolutego' from 1996 and 'Amplifier Worship' from 1998 are being released digitally for the first time. Boris are physically and digitally reissuing two of their early albums: 1996's Absolutego and 1998's Amplifier Worship . The remastered reissues, which are coming via Jack White's Third Man Records, mark the first time that either album has been made available digitally, while both albums will also be pressed on limited edition coloured vinyl (opaque red for Absolutego and lime green for Amplifier Worship ). Absolutego , Boris' debut album, was originally released as a continuous 60-minute piece, and was later given an additional vinyl and CD release via Southern Lord in 2010. This reissue on Third Man will include updated album art and the full record spread across one-and-a-half LPs, with 1997 recording 'Dronevil 2' filling out the other side of the second vinyl. First released in 1998, Boris' second album proper, Amplifier Worship , will see its first-ever reissue in this round of releases. It will come with minimalistic album art from the first-press Japanese CD. Third Man will release Absolutego and Amplifier Worship on November 13, 2020. Boris - Absolutego. Formed in 1992, Boris boldly explores their own vision of heavy music, where words like “explosive” and “thunderous” barely do justice. Using overpowering soundscapes embellished with copious amounts of lighting and billow smoke, Boris has shared with audiences across the planet an experience for all five senses in their concerts, earning legions of zealous fans along the way. -

Page 1 of 163 Music

Music Psychedelic Navigator 1 Acid Mother Guru Guru 1.Stonerrock Socks (10:49) 2.Bayangobi (20:24) 3.For Bunka-San (2:18) 4.Psychedelic Navigator (19:49) 5.Bo Diddley (8:41) IAO Chant from the Cosmic Inferno 2 Acid Mothers Temple 1.IAO Chant From The Cosmic Inferno (51:24) Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo 3 Acid Mothers Temple 1.Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo (1:05:15) Absolutely Freak Out (Zap Your Mind!) 4 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.Star Child vs Third Bad Stone (3:49) 2.Supernal Infinite Space - Waikiki Easy Meat (19:09) 3.Grapefruit March - Virgin UFO – Let's Have A Ball - Pagan Nova (20:19) 4.Stone Stoner (16:32) 1.The Incipient Light Of The Echoes (12:15) 2.Magic Aum Rock - Mercurical Megatronic Meninx (7:39) 3.Children Of The Drab - Surfin' Paris Texas - Virgin UFO Feedback (24:35) 4.The Kiss That Took A Trip - Magic Aum Rock Again - Love Is Overborne - Fly High (19:25) Electric Heavyland 5 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.Atomic Rotary Grinding God (15:43) 2.Loved And Confused (17:02) 3.Phantom Of Galactic Magnum (18:58) In C 6 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.In C (20:32) 2.In E (16:31) 3.In D (19:47) Page 1 of 163 Music Last Chance Disco 7 Acoustic Ladyland 1.Iggy (1:56) 9.Thing (2:39) 2.Om Konz (5:50) 10.Of You (4:39) 3.Deckchair (4:06) 11.Nico (4:42) 4.Remember (5:45) 5.Perfect Bitch (1:58) 6.Ludwig Van Ramone (4:38) 7.High Heel Blues (2:02) 8.Trial And Error (4:47) Last 8 Agitation Free 1.Soundpool (5:54) 2.Laila II (16:58) 3.Looping IV (22:43) Malesch 9 Agitation Free 1.You Play For -

Benjamin, His Harp & Some Friends

Benjamin, his harp and some friends COMPERE Mari Griffith Angharad Evans (harp) Ann Griffiths (harp) Jane Groves (flute) Catherine Handley (flute) Mali Llywelyn (harp) Eluned Pierce (harp) Dylan Rowlands (harp) Eluned Scourfield (harp) & Under 12’s harp trio Martha Holeyman Tomos Xerri & Benjamin Concert Sponsored by BBC Children in Need Appeal Pencerdd Harps Pilgrim Harps Salvi - Lyon & Healy Harps Telynau Vining Harps Norwegian Church Arts Centre Wednesday 13th November 2002 BBC Children In Need accepts no responsibility for this event but we are delighted that such an effort is being made on our behalf. Defnyddiau, crefftwaith a sain o safon uchel am bris cystadleuol Mae telynau ac offer telyn Camac ar gael drwy gwmni Telynau Vining, Caerdydd… Camac harps and accessories are available through Telynau Vining of Cardiff… Telynau pedal Pedal harps Telynau Celtaidd Celtic harps Telynau trydan Electric harps Offer telyn Harp accessories Gorchuddion telyn Harp covers Cerddoriaeth i’r delyn Music for the harp Cysylltwch â/Contact Elen Vining Telynau Vining Cyf 21 Heol Wingfield, Yr Eglwys Newydd, Caerdydd CF14 1NJ Ffôn & Ffacs / Tel & Fax: (029) 2052 9084 E-bost / E-mail: [email protected] Quality of materials, craftsmanship and sound at a competitive price GARDNERS THE PIANO SPECIALISTS OF CARDIFF Established 1953 STOP PRESS ****** CONGRATULATIONS ****** STOP PRESS On Saturday 9th November 2002 Martha Holeyman won second place in the Under 12s Solo Harp Competition at the Gwyl Cerdd Dant. The is a very prestigious National Festival, -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

Albert Schulz As a Cultural Mediator Between the Literary Fields of Nineteenth Century Wales and Germany

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY King Arthur and the privy councillor : Albert Schulz as a cultural mediator between the literary fields of nineteenth century Wales and Germany Gruber, Edith Award date: 2014 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 King Arthur and the Privy Councillor: Albert Schulz as a Cultural Mediator Between the Literary Fields of Nineteenth Century Wales and Germany Edith Gruber Bangor University Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) King Arthur and the Privy Councillor: Albert Schulz as a Cultural Mediator Between the Literary Fields of Nineteenth Century Wales and Germany Edith Gruber Abstract This thesis presents Albert Schulz, a lawyer and autodidact scholar, who won the first prize at the 1840 Abergavenny Eisteddfod with his Essay on the Influence of Welsh Traditions on the Literature of France, Germany, and Scandinavia. -

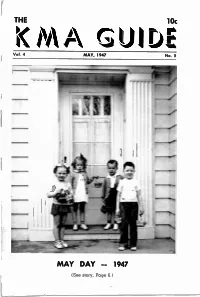

THE 10C MAY DAY -- 1947

THE 10c K M A GUIDE Vol 4 MAY 1947 MAY DAY -- 1947 (See story, Page 6.) 2 THE KMA GUID 7-kc .a;:r The KMA Guide MAIL BOX M AY, 1947 woi osivi Vol. 4 No. 5 Missouri Valley, Iowa The KMA GUIDE is published the first of Am enclosing a dollar for my KMA each month by the Tom Thumb Publish- GUIDE. I have had it ever since it start- ing Co., 205 North Elm St., Shenandoah, ed. I'm making a scrapbook of radio en- Iowa. Owen Saddler, editor; Doris Murphy, tertainers from the pictures in it. I think feature editor; Bill Bailey and Midge Diehl, the GUIDE is the "biggest - little magazine associate editors, Subscription price $1 per off the press. year (12 issues) in the United States; Eunice Edwards. foreign countries, $1.50 per year. Allow two weeks' notice for changes of address and be sure to send old as well as new ad- West Point, Nebraska dress. Advertising rates on request. I enjoy the KMA GUIDE so much, I can hardly wait for it to come each month. Keep up your wonderful work. When are Kenneth, Minnesota you going to print a picture of Edward Please send me the GUIDE for two more May and his family? years. I just couldn't be without it. We Miss Emma Heinemann. like all your entertainers and have KMA (Annette Gertrude, Edward May's 2 year tuned in all day. old daughter, was our "Cover Girl" last Mrs. Gerrit Van Surksum. month. Edward can be seen with his (Thanks. -

Call for Evidence

CC(3) PWA15 Communities and Culture Committee Scrutiny Inquiry :Promoting Welsh Arts and Culture on the World Stage Response from : David Petersen 1 Call for Evidence. Committee Inquiry into the Promotion of Welsh Arts and Culture on the World Stage. 1). How are the Welsh Assembly Government‟s national strategies on promoting arts and culture on the world stage being delivered and coordinated? In my experience WAG‟s national strategies are not being delivered correctly or coordinated properly. See Appendix 1. See Appendix 2. What actually happened was a wasted opportunity to promote Wales because of a lack of experience by WAG officials of the exact requirements and opportunities made available to Wales. Wales was the “Featured Nation” at the Festival in 2008 and as it had been twice before in 2002 and 1997. It is an opportunity for the “Featured Nation” to commission a new musical creation and for it to be given a world premiere at the Festival, in a „state of the art‟ concert venue. In 1997 and in 2002 new work was commissioned from Welsh composers and both received tremendous critical acclaim for the composer and performers as well as reflecting well on Wales as a centre for creativity, both in the local and international press. Because of the unwillingness of the officers responsible to deliver this part of the programme at the Festival, no such new work was commissioned for 2008. Although a new opera had been commissioned by a Welsh composer and was well under way for it to be performed at the Festival, the First Minister wrote to tell me that it would not now be performed.